Sarah Maza

Northwestern University

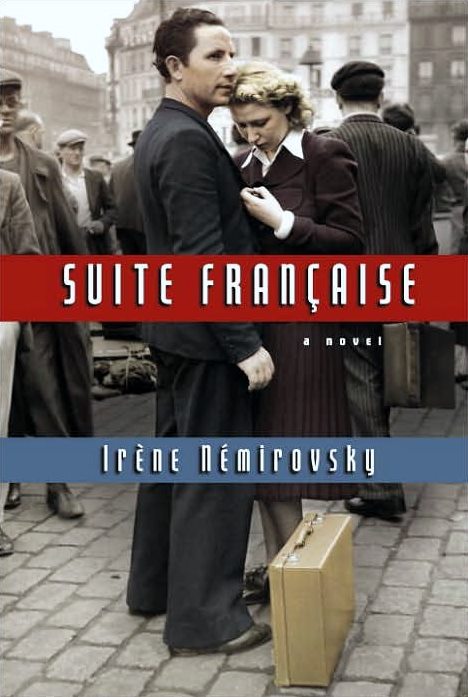

Irène Némirovsky’s Suite Française (1942) is a work that belongs in its own category, a historical novel written in real time. It may not be uncommon for novelists to set stories in what they believe to be a historically resonant present (the years since 9/11 have produced a rash of such fictions), but few can have felt the pressure of that history bearing down on them in the way Némirovsky did. Since the posthumous publication of Suite Française in 2004 (and the English translation in 2006) the contours of Némirovsky’s life have become familiar to anyone with even a glancing interest in literary matters. Born in Russia in 1903 to a wealthy Jewish family, Némirovsky fled the revolution with them and arrived in France in 1919, married Michel Epstein, a banker whose background was similar to hers, and became a successful French-language novelist. Prosperous, successful, well-connected and vocally anti-Communist, the Epsteins too long refused to believe that the Vichy government would let anything happen to them. By the time the menace was clear they did what they could to forestall it, converting to Catholicism, having their two young daughters baptized, and moving to the small town of Issy-l’Évêque in Burgundy, the home of their children’s nanny. It was there that Irène wrote the first two parts of a Suite which was to comprise five novellas chronicling the French defeat and occupation as well as later events as they developed. Némirovsky’s writing was interrupted by her arrest and deportation, which was shortly followed by her husband’s. Both died at Auschwitz in 1942. The manuscript of Suite Française was discovered sixty years later by one of the author’s daughters.[1]

Némirovsky’s vivid fiction-in-real-time –not to mention the author’s life story– has a great deal to offer to undergraduates studying the period, although some caveats apply. The whole of Suite is long, over four hundred pages, more than most of us would dare assign for a week’s reading. Unless blessed with highly motivated students or very long semesters, most instructors wishing to use the book will probably have to choose between the two novellas, and I would guess that students would do better with the second story, “Dolce,” than with the first, “Storm in June.” This is not to minimize the historical interest of “Storm,” which intertwines the tales of several groups of people fleeing Paris in June of 1940 ahead of the German invasion. This first novella, however, is episodic in structure, cuts back and forth between many characters in various locations, and deals with subtle class distinctions that may not be readily accessible to American students. The characters escaping the German advance include the haut-bourgeois Péricand clan –a ruthlessly snobbish mother, four children, a doddering grandfather and assorted retainers–, the heinously selfish best-selling writer Gabriel Corte and his flinty mistress Florence, the equally narcissistic aesthete Charles Langelet, a good-hearted but unlucky lower-middle-class couple, a priest zealously engaged in the rescue of a flock of resentful Parisian orphans, and a wounded soldier who has found refuge in a farmhouse. Since most of the characters are upper-class and none belong to the urban working classes, the story hardly shows a full spectrum of French society. Novice readers may be confused, for instance, about the social status of the soldier Jean-Marie Michaud, a student regarded as upper-class in the farmhouse where he is recovering, but whose parents are lowest on the scale of Parisian characters.

Némirovsky’s vivid fiction-in-real-time –not to mention the author’s life story– has a great deal to offer to undergraduates studying the period, although some caveats apply. The whole of Suite is long, over four hundred pages, more than most of us would dare assign for a week’s reading. Unless blessed with highly motivated students or very long semesters, most instructors wishing to use the book will probably have to choose between the two novellas, and I would guess that students would do better with the second story, “Dolce,” than with the first, “Storm in June.” This is not to minimize the historical interest of “Storm,” which intertwines the tales of several groups of people fleeing Paris in June of 1940 ahead of the German invasion. This first novella, however, is episodic in structure, cuts back and forth between many characters in various locations, and deals with subtle class distinctions that may not be readily accessible to American students. The characters escaping the German advance include the haut-bourgeois Péricand clan –a ruthlessly snobbish mother, four children, a doddering grandfather and assorted retainers–, the heinously selfish best-selling writer Gabriel Corte and his flinty mistress Florence, the equally narcissistic aesthete Charles Langelet, a good-hearted but unlucky lower-middle-class couple, a priest zealously engaged in the rescue of a flock of resentful Parisian orphans, and a wounded soldier who has found refuge in a farmhouse. Since most of the characters are upper-class and none belong to the urban working classes, the story hardly shows a full spectrum of French society. Novice readers may be confused, for instance, about the social status of the soldier Jean-Marie Michaud, a student regarded as upper-class in the farmhouse where he is recovering, but whose parents are lowest on the scale of Parisian characters.

“Storm in June” also foregrounds Némirovsky’s main limitation as a novelist, a tendency towards reductionist caricature, especially of the upper classes. There is no question that she was an accomplished and clever writer, particularly adept at startling shifts in points of view: one of the chapters of “Storm” is told from the perspective of the Péricands’ cat, the pivotal romantic scene in “Dolce” unfolds through the eyes of a distracted and uncomprehending child, and in the latter story we are suddenly introduced to the inner life of an unsympathetic character, Madame Angellier, who until then has existed only in the perception of her beleaguered daughter-in-law Lucile. Too often, though, and especially in “Storm,” the characters are two-dimensional. Some prove sympathetic, like the generous and long-suffering lower-middle-class Michauds, most are appalling: the writer and his mistress exploit each other, the priest despises and resents the children he purports to save, Madame Péricand’s behavior makes a savage mockery of the Catholic principles she ostentatiously espouses, and so on.

Némirovsky’s jaded view of French society is, of course, understandable, and students apprised of her biography and who read her remarkable author’s diary included in the English edition of the novel will easily get the point: “My God!,” she wrote, “What is this country doing to me? Since it is rejecting me, let us consider it coldly, let us watch as it loses its honor and its life” (p. 373). “Storm” is historically vivid, with dramatic depictions of bombings and strafings, and acute recreations of the experience of fear: “Then a dark shape would glide across the star-covered sky and the laughter would stop” (p. 46). Ultimately, though, Némirovsky’s purpose in “Storm” is trans- or super-historical, as she herself noted programmatically in her diary: “Never forget that the war will be over and that the entire historical side will fade away…Reread Tolstoy. Inimitable descriptions but not historical” (p. 383). The acid message of “Storm” is that people under pressure will behave like the Péricand’s house cat, who, once exposed to nature, turns savage and claws a bird to death; the cat’s newfound brutality is echoed in the behavior of most of the other characters, as when Langelet steals petrol from a besotted young couple to escape the bombings, or the orphans in Father Philippe’s care turn on the priest and stone him to death. Némirovsky had ambitions to make a lasting statement about human nature, but alas, she was no Tolstoy.

In “Dolce,” however, history is inescapable because it structures the relationships between the main characters. The plot, which oddly echoes Vercors’ Le Silence de la mer (also written in hiding at around the same time), centers on the intimate cohabitation of French and German characters.[2] The German occupation is now under way, and in the fictional small town of Bussy a pair of proper bourgeoises, Lucile Angellier and her mother-in-law, are forced to provide lodging in their house for a German officer, Bruno von Falk, who turns out rather predictably to be a perfect gentleman and skilled pianist, and soon proves attractive to Lucile. The back story of Lucile’s marriage sets the pattern for relationships between the three: her prisoner-of-war husband is both the object of his mother’s excessive devotion, and an adulterous cad who has long neglected Lucile. The older Madame Angellier’s resentment of the foreigner who has usurped her adored son’s place flows as inevitably from the situation as does Lucile’s perception of him as an idealized substitute for her spouse. Here again, Némirovsky tends to fall into easy caricature. The local nobility, for instance, threatened by any expression of self-assertion by the “little people,” are in fact, if not in principle, grateful to the occupiers: “Yes, the Viscountess the Montmort had reached the point where she wondered if she should not thank the Good Lord for the German occupation of France” (p. 312). (Némirovsky’s persistently vitriolic portrayals of older upper-class women must be related to her troubled relations with her own cold and narcissistic mother.)

The great strength of “Dolce,” however, is its clear-sighted portrayal of the psychic and practical ambiguities of occupation. The novella shows not only that people of the same class (Madame Angellier and her daughter-in-law) could react very differently to the occupiers, but even more trenchantly that attitudes within the same people could vary from one situation, one moment to the next. In “Dolce,” Némirovsky excels at evoking the shifting mixture of curiosity, fear, and attraction between occupier and occupied. Class differences emerge under pressure, as when the middle-class Madame Angellier bitterly considers the local nobility’s tolerance of the invader: “These aristocrats were part foreigner themselves, after all, if you looked closely enough” (p. 333). Both rich and poor collaborate for reasons of self-interest, women are drawn to the fair-haired young warriors, and while Lucile’s romance with Bruno causes a scandal, a range of townspeople soon pressure her into using her connection with him to get them something they want. The Germans themselves are equally perplexed by the unstable compound of bonhomie and hostility they encounter on a daily basis, “they tried to work out whether this defeated people hated them, tolerated them, or liked them” (p. 219).

Students should soon come to understand upon reading “Dolce” (especially if it is paired with the works of Robert Gildea, John Sweets, Richard Vinen and others) that there were no stable or predictable behaviors in this fraught situation, and no such thing as “the French.” And any portion of Suite Française takes on increased depth and meaning with a reading of the novel’s two appendices. The first, the author’s writing diary, poignantly evokes the urgency Némirovsky felt about getting her work completed. “Which scenes deserve to be passed on for posterity?’ she wondered while mapping out episodes, listing characters, and sketching out plans for the three novellas that would round out her historical epic (p. 374). Most troubling and memorable are the letters in the second appendix, a heart-rending chronicle of the Epsteins’ descent into hell: the worsening financial troubles, confusion about the first anti-Semitic laws, the move to the countryside, Irène’s arrest and final letters, Michel’s desperate campaigns to locate and save her (he touted the anti-Semitic content of some of her novels to the authorities), and finally his own disappearance. In conjunction with Némirovsky’s fiction, the two appendices, especially the letters, should provide a rich source of discussion about history and fiction as well an indelible introduction to France’s darkest years.

Irène Némirovsky, Suite Française, trans. Sandra Smith (New York: Vintage Books, 2006) originally published as Suite française (Paris: Denoël, 2004).

- For biographical details see Jonathan Weiss, Irène Némirovsky: Her Life and Works (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007).

- Le Silence de la mer, a classic novel of occupied France, was written and published illegally in 1942. Vercors was the nom de guerre of Jean Bruller, a member of the Resistance who founded the clandestine Éditions de Minuit. The novel describes the experience of a German officer billeted with an elderly man and his niece, both of whom refuse to speak to him. While the premises of both novels are similar, Vercors’ tale is a darker parable about the chasms that wars create between human beings.

My Vichy France seminar just analysed “Storm in June” (the first half of “Suite Francaise) very successfully, having read Julian Jackson, Marc Bloch, and a selection of other analyses of the Fall of France. I used it as a vehicle for a comparative assignment on the Exodus and they resonated to the variety of perspectives and the sense of chaos embodied in the chopped-up narrative. I don’t know how well they would have responded without all the previous readings but I was pleased with the experiment. I have had individual students work on the second novella in the past and loving it, but the first part is well worth a look.

Liana