Barbara C. Pope

University of Oregon, Emerita

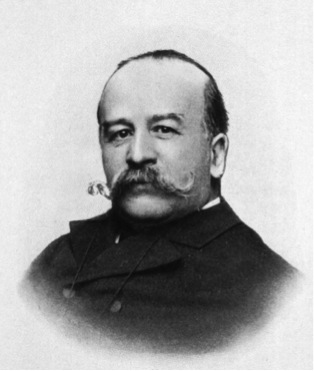

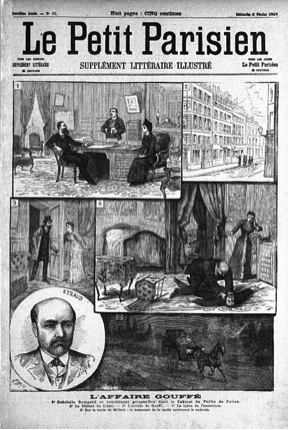

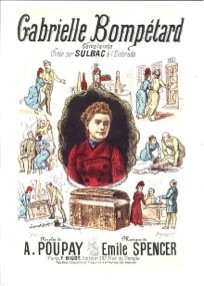

On the evening of 26 July 1889, an upstanding, womanizing widower, a wealthy bailiff named Toussaint-Augustin Gouffé, went to meet an alluring young woman in her central Paris apartment. He emerged the next morning, strangled, sewn into a burlap sack and squeezed into a great trunk, the victim of a grotesque, baroque plot. The perpetrators, Gabrielle Bompard and her lover, Michel Eyraud, took the trunk on a train heading south. The day after their arrival in Lyon, Eyraud rented a carriage and rode off into the countryside, where he tossed Gouffé’s body onto a river bank, broke up the trunk with a hammer and scattered its parts. Bompard and Eyraud  eventually made their way to America where he continued his life’s métier as a shameless and inexplicably effective swindler, taking on various names, disguises and schemes, and introducing the petite Gabrielle as his daughter.

eventually made their way to America where he continued his life’s métier as a shameless and inexplicably effective swindler, taking on various names, disguises and schemes, and introducing the petite Gabrielle as his daughter.

It took almost four months, and the dogged persistence of the chief of the Paris Sûreté, Marie-François Goron, to prove that the putrifying corpse in an unmarked grave near Lyon was the missing bailiff. It took almost a year, trailing Eyraud over two continents and five countries, to bring him to justice. The progress of the scoundrel, the manhunt, and the application of pioneering criminal science are all part of the tale that Steven Levingston weaves in Little Demon in the City of Light: A True Story of Murder and Mesmerism in Belle Epoque Paris. But, as the title portends, they are not, for the author, the most significant aspect of the tale. Inspired by Ruth Harris’s article “Murder under Hypnosis,”[1] Levingston spent eight years researching and writing about the first case in which hypnosis was used as a defense in a criminal trial. The central question was whether the vulnerable 21-year old Gabrielle Bompard was guilty of murder if she was under the suggestive and hypnotic powers of a lover twice her age. Was she a seductress or a victim? The medical and legal arguments are at the heart of Levingston’s quest.

The title of Levingston’s book suggests an obvious parallel to Erik Larson’s The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America (2003). The subject of Larson’s bestseller was the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 and the serial killer who used it as cover to kill countless women. Yet the two books tell a very different story. Larson

gives an extremely detailed account of how the fair was built, the rivalries and obstacles faced by the architects and planners, and the effect of this extraordinary exhibition on the city. This is an even larger part of his book than the murders committed only a stone’s throw away from the celebration, completely hidden from view. We are still not sure how many unsuspecting men, women and children fell victim to the psychopath H. H. Holmes. In contrast, although the Paris Exhibition of 1889 serves as a backdrop to the first chapter of Levingston’s book, it soon drops out of sight in favor of a blow-by-blow account of the criminal investigation and its controversial denouement, most of which occurred with the full and happy awareness of the Parisian populace. What the two books have very much in common is the notion of the late nineteenth-century city as spectacle. And nowhere was spectacle a more important aspect of urban living than in Paris: the cabarets of Montmartre; the scores of scandal-mongering penny presses; the daily crowds at the morgue; the wax-statue recreation of the current crimes at the Musée Grévin; even Charcot’s Tuesday lectures at the Saltpêtrière, where women suffering from delusions and hysteria were put on display.

The alluring subtitle of Levingston’s book, “murder and mesmerism” is misleading. No nineteenth-century scientist or doctor would have called himself a “mesmerist.” The outlandish claims and notoriety of the eighteenth-century doctor Franz Anton Mesmer had almost done in the possibility that anyone would use hypnotism for medical purposes. Yet hypnotism was revived, and by none other than France’s most charismatic doctor, Jean-Martin Charcot. Indeed, it was even fashionable, a popular entertainment in cabarets, theaters, and upper-class salons.

The alluring subtitle of Levingston’s book, “murder and mesmerism” is misleading. No nineteenth-century scientist or doctor would have called himself a “mesmerist.” The outlandish claims and notoriety of the eighteenth-century doctor Franz Anton Mesmer had almost done in the possibility that anyone would use hypnotism for medical purposes. Yet hypnotism was revived, and by none other than France’s most charismatic doctor, Jean-Martin Charcot. Indeed, it was even fashionable, a popular entertainment in cabarets, theaters, and upper-class salons.

Although Charcot and his acolytes dominated French psychology in this era, he was not without his critics. Upstarts from the provinces, the so-called Nancy School, challenged his notion that only hysterics could be fully hypnotized. They also disputed his insistence that a hypnotized hysterical woman could and would refuse to commit criminal acts that went against her own moral sense. The Nancy School, whose leading lights were a kindly country doctor, a renowned psychiatrist and a law professor, made bigger claims for the power of suggestion and hypnosis. Both the psychiatrist Hippolyte Bernheim and Dr. Ambrose-Auguste Liébeault had found hypnotism useful in curing some of their patients, while Professor Jules Liégeois tended to focus on hypnotism’s more spectacular and scary manifestations. He concurred with Bernheim’s theorizing and experiments on the power of suggestion and believed that a good hypnotist could make anyone do anything. This raised the frightening possibility that hypnotism could foment crime and revolutions. The arguments between the two medico-legal factions came to a head at the trial of Gabrielle Bompard and Michel Eyraud.

In the build up to that trial, Levingston gives a clear explanation of the differences between the French and Anglo-American criminal justice system. In major cases, an examining magistrate or juge d’instruction played a central role in any investigation. He had broad, almost unlimited powers to interrogate witnesses, hold suspects, authorize searches, even reenact crimes scenes. All of which the judge assigned to the case, the stalwart Paul Dopffer, did. He even negotiated between the Paris and Lyon police and judiciary when the provincials revealed their usual propensity for non-cooperation and defensiveness. After months of investigation he produced a dossier which was handed over to the court, where the presiding judge (one of three on the bench during the proceedings) used Dopffer’s compilation of evidence, arguments, and conclusions to formulate trial questions.

In the build up to that trial, Levingston gives a clear explanation of the differences between the French and Anglo-American criminal justice system. In major cases, an examining magistrate or juge d’instruction played a central role in any investigation. He had broad, almost unlimited powers to interrogate witnesses, hold suspects, authorize searches, even reenact crimes scenes. All of which the judge assigned to the case, the stalwart Paul Dopffer, did. He even negotiated between the Paris and Lyon police and judiciary when the provincials revealed their usual propensity for non-cooperation and defensiveness. After months of investigation he produced a dossier which was handed over to the court, where the presiding judge (one of three on the bench during the proceedings) used Dopffer’s compilation of evidence, arguments, and conclusions to formulate trial questions.

Many Americans will be surprised by the free-wheeling courtroom scene that takes up about one-fifth of the book. Tout Paris fought for seats in the audience, and the less fashionable (and presumably more needy) scalped tickets. The presiding judge, not the prosecutor or avocat, led the questioning, starting with the accused. Lawyers interjected and objected, but had little leeway to counter false claims. Their major role came at the end of the trial, in closing arguments or, better, orations, which, as in all notorious cases, won the applause of their appreciative audience. In the Bompard-Eyraud proceedings even a juror interjected with a question, and expert witnesses were asked to comment on each other’s testimonies. Liégeois, a witness for the defense, made the most stunning intervention. Despite the presiding judge’s refusal to allow Liégeois to hypnotize Bompard privately, or, more outrageously, conduct a demonstration in the courtroom, the law professor still managed to hold court—or, at least, hold it up. Citing article 319-s-2 of the criminal code, he asserted that he had the right to give uninterrupted testimony. Thus he caused an early adjournment one day in order to bore the court and quite thoroughly irritate the judge for several hours the next. (Gabrielle Bompard fell peacefully asleep in the dock while her star witness droned on.)

In the end, Henri Robert, Bompard’s well-regarded avocat, did not use the Nancy defense. Rather, in an attempt to gain some mercy for his client, he fell back upon the Charcot hypothesis that a hysterical woman, even under hypnosis, would not act against her own morals. He thus saved Eyraud’s accomplice from the guillotine.

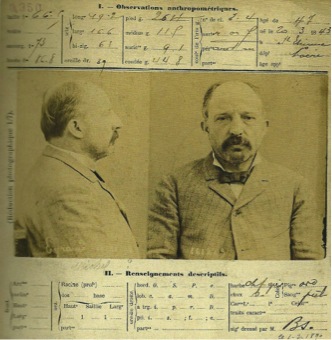

The trial scenes were my favorite part of this well-researched, very readable book. But it offers many other pleasures. Levingston provides biographical vignettes of each of the major characters and an epilogue that reports their subsequent fates. His descriptions, while sometimes overheated (e.g., the Belle Epoque was a time of “unrelenting dread,” p. 2), sparkle with lively details, like Mesmer’s “lilac silk coat” and the odor of death that everywhere trailed Alexandre Lacassagne, the chief of forensic science at the University of Lyon. And, oh, what an investigatory team they were! The unrelenting Chief Goron with his hunches and skillful manipulation of the press; his worthy sidekick, Inspector Pierre-Fortune Jaume; the pioneering criminologist Alphonse Bertillon measuring the suspects for signs of their criminality; and most of all, Lacassagne himself, elbow deep in the muck of what was left of poor Gouffé, a scene worthy of any CSI episode.

Steven Levingston is a journalist, not an academic historian. He includes a full bibliography and illustrations (although, the full-length photograph of Bompard in the publisher’s press release would give readers a better idea of her charms than the rather unremarkable headshot chosen for the book). For a more detailed and subtle delineation of the Charcot and Nancy Schools, readers can turn to Ruth Harris’s Murders and Madness: Medicine, Law and Society in the Fin de Siècle (1989). For evolution of urban sensationalism, there is Vanessa R. Schwartz’s wonderful Spectacular Realities: Early Mass Culture in Fin-de-Siècle Paris (1998). Still Levingston’s book serves as a good introduction to the state of French policing, law, and psychology at the end of nineteenth century. It is a fascinating story well told, one that is, in fact, quite mesmerizing.

Steven Levingston. Little Demon in the City of Light: A True Story of Murder and Mesmerism in Belle Epoque Paris. New York: Doubleday, 2014.

- “Murder under Hypnosis in the Case of Gabrielle Bompard: Psychiatry in the Courtroom of Belle Epoque Paris,” in The Anatomy of Madness: Essays in the History of Psychiatry, Vol. 2. Edited by William F. Bynum, Roy Porter, and Michael Shepherd. New York: Routledge, 1985.