Sandra Ott

University of Nevada, Reno

Romain Slocombe’s disturbing yet riveting novel, Monsieur le Commandant: A Wartime Confession, provides an intriguing lens through which to explore the inner thoughts of a fictional anti-Semitic collaborationist, Paul-Jean Husson.[1] First published in French in 2011 to considerable acclaim, the novel appeared in English in 2013. A decorated veteran of the Great War, an ardent Pétainist, a member of the Académie Française and the Franco-German Committee, Husson is above all a well-known author whose friends include Céline, Brasillach and Jean Luchaire. Husson is also on good terms with several high-ranking German officers, including Otto Abetz (Hitler’s ambassador to Vichy headquartered in Paris and head of the Franco-German Committee) and Sonderführer Gerhard Heller, a Francophile who headed the Nazi propaganda office in Paris responsible for censorship. Heller organized two trips for French writers to Weimar, where they met Goebbels.[2] The fictitious Husson was among them.

The novel largely consists of a 172-page letter composed by Husson in September 1942. The letter is both a confession and an appeal to a Nazi officer, Sturmbannführer Schöllenhammer, the Commandant in charge of Husson’s pretty provincial town in Normandy. The reasons underlying Husson’s letter are slowly revealed as the renowned writer painstakingly reconstructs the events that lead him to seek the German’s assistance. The purportedly historical documents that follow the letter offer reflection on Husson’s status as a collaborationist, the ways in which his fellow townspeople coped with the occupation, and the fates of the novel’s main characters.

The novel largely consists of a 172-page letter composed by Husson in September 1942. The letter is both a confession and an appeal to a Nazi officer, Sturmbannführer Schöllenhammer, the Commandant in charge of Husson’s pretty provincial town in Normandy. The reasons underlying Husson’s letter are slowly revealed as the renowned writer painstakingly reconstructs the events that lead him to seek the German’s assistance. The purportedly historical documents that follow the letter offer reflection on Husson’s status as a collaborationist, the ways in which his fellow townspeople coped with the occupation, and the fates of the novel’s main characters.

In his letter, Husson takes the reader back to the 1930s, when his son, Olivier, met and married a stunning young German film actress, Ilse Wolffsohn. Her blonde and blue-eyed beauty at once captivates the elder Husson. Yet he soon suspects that she is Jewish and hires a private investigator to check on her family background. The report confirms his worst fears. Ilse had successfully applied for French nationality shortly before the war broke out in 1939. She gives birth to a daughter. Olivier is mobilized and becomes increasingly estranged from his anti-Semitic father. Husson publishes vitriolic attacks on the Jews, even as he becomes besotted with Ilse. His sexual desire for her sharply contradicts the revulsion and notorious hatred he feels for Jews. As German troops advance on Paris, Husson, Ilse and the child get caught up in the exodus of June 1940. Slocumbe’s account of their journey through the chaos and danger resonates with Irène Némirovsky’s fictitious portrait of the flight south from Paris.[3] On their return to Normandy, Husson and his daughter-in-law face Vichy’s increasingly anti-Semitic policies, as well as threats from the so-called French Gestapo. French thugs (who worked for the notorious Bonny-Lafont gang, among others) blackmail Husson for protecting a Jewess.[4] He witnesses their brutal torture of two young resisters, one of whom is the son he had conceived in a casual liaison decades earlier. Slocombe portrays the violence vividly.

As German troops advance on Paris, Husson, Ilse and the child get caught up in the exodus of June 1940. Slocumbe’s account of their journey through the chaos and danger resonates with Irène Némirovsky’s fictitious portrait of the flight south from Paris.[3] On their return to Normandy, Husson and his daughter-in-law face Vichy’s increasingly anti-Semitic policies, as well as threats from the so-called French Gestapo. French thugs (who worked for the notorious Bonny-Lafont gang, among others) blackmail Husson for protecting a Jewess.[4] He witnesses their brutal torture of two young resisters, one of whom is the son he had conceived in a casual liaison decades earlier. Slocombe portrays the violence vividly.

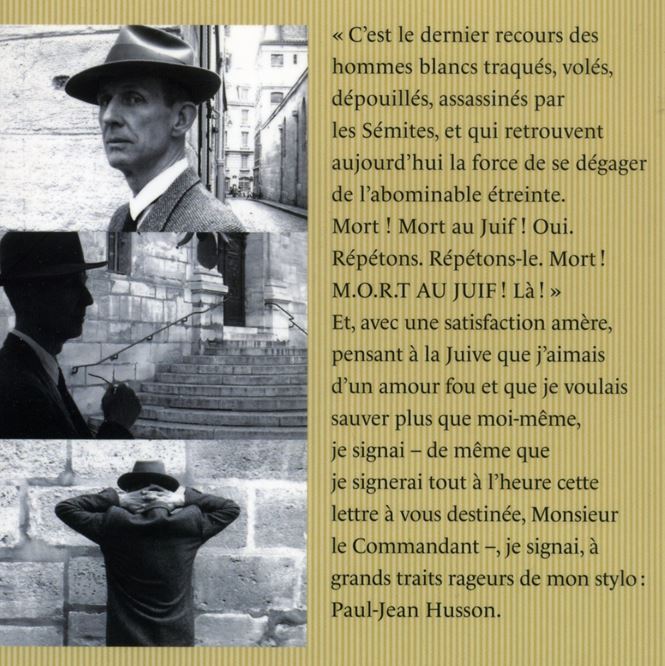

Father and son angrily break off relations when Olivier announces his intention to join de Gaulle in England. Ilse gives birth to a son in March 1941. Husson finds the infant repulsive. Yet he is irresistibly drawn to “the lovely blonde Jewess” whom he now “loves like a fool, an old fool.”[5] As Vichy implements increasingly repressive anti-Semitic laws, Husson faces a dilemma: how can he protect the object of his love and yet also remain faithful to his anti-Semitic sentiments? The way in which he finally resolves this dilemma is central to the story. Initially, Husson seeks to deflect suspicions about Ilse by attacking Jews in the press. When Ilse has an unwanted pregnancy, Husson must find “one final solution” to the problems he and she face. In an act of ultimate betrayal, he places the fate of Ilse in the hands of his friend, Sturmbannführer Schöllenhammer. Husson does so “in faith and friendship” and beseeches the Commandant to “treat her well.”[6]

During the occupation, French citizens sent three to five million letters of denunciation, anonymous or signed, to the Vichy and German authorities.[7] In France, as in Nazi Germany, such letters often revealed the private, instrumental motives of their authors. Such accusatory practices are an “important point of contact between individual citizens and the state, one that embodies a whole set of unarticulated decisions about loyalties to the state, on the one hand, and to family and fellow citizens on the other.”[8] Husson articulates his decision “to wipe the slate clean, all or nothing” at the very beginning of his letter. His betrayal of Ilse to the German authorities enables him to “relinquish attachment to everything (he) once desired.”[9] Husson refuses to remain anonymous. He treats his denunciation as an act of civic virtue and as a redemptive act in the eyes of God.

Like Brasillach and other literary collaborationists, Husson is ideologically drawn to the Nazi idea of a new Europe. His public stance on the eradication of Jews makes him a target for the post-liberation purge. The authorities arrest Husson in August 1944. The prosecutor in the court of justice calls for the death penalty, but the judge and jurors find extenuating circumstances and sentence him to fifteen years with hard labor. Pardoned in 1952, Husson dies in a monastery in 1959. (The venue of his death reflects his desire for redemption, which he seeks via a darkling road.”)[10]

Monsieur le Commandant offers the reader a rare opportunity to step inside the mind of an anti-Semitic collaborationist who is torn by wildly conflicting sentiments about the Jews in general and the Jewess that he desires in particular. The novelist creates a character in Paul-Jean Husson that is highly believable and chillingly unpleasant. The post-liberation trial dossiers of collaborationists reveal similar portraits of men who believed in Pétain’s desire to protect and to save the French, in Franco-German partnership, and in the need to rid France of Jews, Communists and Freemasons in order to achieve a new European order. Husson offers a fresh perspective on Pierre Laborie’s concepts of “double-think” and the “dual man” that are normally applied to the ordinary French citizen:

Monsieur le Commandant offers the reader a rare opportunity to step inside the mind of an anti-Semitic collaborationist who is torn by wildly conflicting sentiments about the Jews in general and the Jewess that he desires in particular. The novelist creates a character in Paul-Jean Husson that is highly believable and chillingly unpleasant. The post-liberation trial dossiers of collaborationists reveal similar portraits of men who believed in Pétain’s desire to protect and to save the French, in Franco-German partnership, and in the need to rid France of Jews, Communists and Freemasons in order to achieve a new European order. Husson offers a fresh perspective on Pierre Laborie’s concepts of “double-think” and the “dual man” that are normally applied to the ordinary French citizen:

who is both one thing and the other, more as a result of external pressures than out of self interest… In order to survive, the French had to learn very quickly to live with two images of themselves: one public face for the sake of appearances and survival, and one hidden face to preserve a certain way of being and to take action.[11]

Husson is not an ordinary Frenchman. Yet he is “both one thing and the other.” He has two faces: one public, anti-Semitic face that was not created for the sake of appearances but out of hatred for the Jews and ideological conviction; and one private, hidden face that, in contradictory fashion, sought to save the object of his illicit desire. Ideological commitment, self-interest, and carnal desire collide in the novel with tragic consequences.

Slocombe’s story contains many of the themes found in the trial dossiers of suspected collaborators and collaborationists: human folly, uncertainty, ambiguity, desire, vengeance, greed, opportunism, and betrayal. The author deftly places his grass roots level portrait of a collaborationist writer within the wider socio-political context of occupied France and collaborationist circles in Paris. His brief sketches of Franco-German relations resonate with accounts of sociability between the occupied and occupiers in post-liberation trial dossiers. Husson participates in receptions and buffets hosted by Otto Abetz and other high-ranking Germans with whom he is on familiar terms.

Commensality and hospitality sometimes led to the formation of social ties and a measure of social solidarity between the French and the Germans in occupied France. The post-liberation authorities often used Franco-German sociability as a means of measuring the extent to which an individual had entered into relations with the enemy and whether such relations had engendered anti-national sentiments, endangered the lives of French citizens, or posed a threat to national security. In Husson’s case, his vicious anti-Semitic diatribes in the press constituted ample grounds for his arrest, prosecution, and imprisonment. But the trial dossiers of real-life collaborationists also show that the postwar authorities sometimes used epistolary relations with the enemy as equally firm grounds for delivering a harsh verdict in the court of justice.[12]

Commensality and hospitality sometimes led to the formation of social ties and a measure of social solidarity between the French and the Germans in occupied France. The post-liberation authorities often used Franco-German sociability as a means of measuring the extent to which an individual had entered into relations with the enemy and whether such relations had engendered anti-national sentiments, endangered the lives of French citizens, or posed a threat to national security. In Husson’s case, his vicious anti-Semitic diatribes in the press constituted ample grounds for his arrest, prosecution, and imprisonment. But the trial dossiers of real-life collaborationists also show that the postwar authorities sometimes used epistolary relations with the enemy as equally firm grounds for delivering a harsh verdict in the court of justice.[12]

The confessional nature of Husson’s letter to the Commandant makes clear that the two men had forged a close, personal relationship. Husson admires the Nazi officer and feels that they have “an understanding.” Yet we know very little about Schöllenhammer. In this respect, the novel provides an incomplete portrait of day-to-day Franco-German relations during the Occupation. At the end of the book, Slocombe refers to a fictional documentary, made by a fictional German director in 2008, about “Elsie Berger’s French Family.”[13] The German Commandant dies on the Eastern front. Fragments of a poem by real-life poet Paul Claudel, copied by Husson and saved by his German confidante, are found in the Commandant’s home in Leipzig. Fact and fiction thus continually intertwine in this intriguing novel.

Husson’s carnal desire for his daughter-in-law, his viciously anti-Semitic sentiments, the tensions surrounding Ilse’s likely fate as a Jew in occupied France, and the sheer power of Slocombe’s prose make this novel very compelling to read. The book raises important questions about morality and immorality, human choice and agency in wartime France. Husson is a credible collaborationist who perceives himself as a normal French nationalist and who fails to recognize the fanaticism in his own thinking and actions. Yet the format Slocombe uses to tell the story—an extremely long letter–is not credible. It is highly unlikely that a collaborationist in contact with a German officer on a close, social basis would ever write such a confessional letter to him, or that such a letter would ever be read by the occupier. Archival research in trial dossiers shows that the French and the Germans did sometimes forge close friendships that entailed the sharing of intimate secrets. When they did occur, such exchanges typically took place in private, face-to-face encounters, usually over a glass of wine or two.[14]

Monsieur le Commandant will be of great interest to those who study and write about the German occupation. The work would be highly suitable for an interdisciplinary approach that draws upon fiction (e.g. Némirovsky’s Suite Française), film (e.g. Lacombe, Lucien by Louis Malle) and local studies of everyday life in occupied France. Slocombe offers new, valuable perspectives on the intersections of history and fiction. His novel illuminates the role that fictional narratives can play in our understanding of the German Occupation of France and anti-Semitism through the thought processes of a collaborationist gifted enough as an author to articulate his contradictory feelings with a terrible precision.

Romain Slocombe, Monsieur le Commandant: A Wartime Confession (London: Gallic Books, 2013). Monsieur le Commandant (Paris: Editions NiL, 2011).

- I am very grateful to Ken Mouré for his stimulating comments on my observations about this novel.

- The trip was intended to foster cultural ties between France and Nazi Germany.

- Irène Némirovsky, Suite Française (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006). See also Hanna Diamond, Fleeing Hitler, France 1940 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- The gang’s members were notorious criminals who organized kidnappings and assassinations for the Germans and tracked down their enemies. See Richard Vinen, The Unfree French: Life under Occupation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), pp. 127-128, 240.

- Romain Slocombe, Monsieur le Commandant: A Wartime Confession (London: Gallic Books, 2013), p. 110.

- Ibid., p. 168.

- André Halimi, La Délation sous l’occupation (Paris: Éditions Alain Moreau, 1983), p. 7.

- Sheila Fitzpatrick & Robert Gellately (eds.), Accusatory practices: Denunciation in Modern European History, 1789-1989 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), p. 2.

- Slocombe, Monsieur le Commandant: A Wartime Confession, p. 10.

- Ibid., pp. 11, 170.

- Pierre Laborie, “1940-1944: Double-Think in France,” in Sarah Fishman, Laura Lee Downs, Ioannis Sinanogl et al, eds. France at War: Vichy and the Historians (London and New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2000), p. 186.

- See Sandra Ott, “The Informer, the Lover and the Gift-Giver: Female Collaborators in Pau, 1940-1946,” French History, vol. 22, issue 1 (2008), pp. 94-114.

- Elsie Berger was the stage name of Ilse.

- See Sandra Ott, “Duplicity, Indulgence and Ambiguity in Franco-German Relations, 1940-1946,” History and Anthropology, Vol. 20, No. 1 (2009), pp. 57-97.