Issue 2

Patrick Rambaud’s trilogy of novels about Napoleon is doubly unusual. His attitude toward historical fiction is similar to that of the once famous André Chamson, director of the Archives Nationales in the 1960s, who described his own novels as romans dans l’histoire, rather than romans historiques or – worse – histoires romancées, such as those of Alexandre Dumas. Like Chanson, Rambaud repudiates these other forms, and seeks instead to relive historical events through personal close ups based on first-hand accounts. Rambaud is also distinctive in writing about the inglorious Napoleon, the loser of a major battle in 1809, the organizer of defeat in Russia in 1812, and the ruler of an island kingdom rather than a continental empire in 1814-15. Here, then, is one author combining two unusual perspectives over three novels. Students will have much to discuss.

Patrick Rambaud’s Napoleonic Trilogy

Michael Sibalis

Wilfrid Laurier University

Napoleon himself described his life as a roman, so it is not surprising that countless novelists, from the very best (Leo Tolstoy, Anthony Burgess, etc.) to the most mediocre, have been tempted to write their own version of the Imperial saga. As recently as November 2010, former French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing brought out La Victoire de la Grande Armée (Plon), a fantasy in which the Emperor

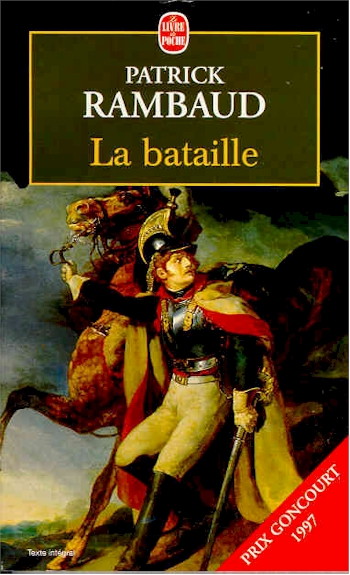

triumphs in Russia in 1812, founds the United States of Europe, abdicates in favor of his son (with Eugène de Beauharnais as Regent), and then dedicates himself to the promotion of liberalism and world peace. Alas! historical reality is far less pleasant to contemplate than this and Napoleonic glory was always – in H.G. Wells’s words – “caked over with human blood.” Three outstanding French novels about the decline of the First Empire, by the prolific Patrick Rambaud, author of at least thirty books but probably best known for those lampooning Nicolas Sarkozy, have recently appeared in English. These convey vividly all the drama and horror of Napoleon’s real story: The Battle (La Bataille, 1997), The Retreat (Il Neigeait, 2000), and Napoleon’s Exile (L’Absent, 2003).[1] They have enjoyed immense public success and critical acclaim in France – the first won Rambaud both the Prix Goncourt and the Grand Prix du Roman de l’Académie Français – and are now fortunately available to an “Anglo-Saxon” readership.

The Battle gets its title and theme from Balzac, who never carried through on his plan to write a novel on the two-day Battle of Essling (21-22 May 1809). Balzac intended to focus exclusively on the experience of battle: “only cannon, horses, two armies, uniforms. On the first page, the cannon roars; on the last it falls silent.”[2] Rambaud’s version is somewhat different. It centers on the experiences of Louis-François Lejeune (1775-1848), a painter and staff officer who really lived and fought under Napoleon and who left memoirs, but Rambaud fleshes out the story with numerous other characters, both real and invented. Thus, Rambaud’s Lejeune carries on a love affair with a young woman who turns out to be an Austrian spy. He is also close friends with Henri Beyle (the future Stendhal, who actually was in Vienna at the time). In the novel, Beyle happens to share lodgings with Friedrich Staps, the fanatical German student who tried to assassinate Napoleon in October 1809, an event that Rambaud moves forward to May. All this adds drama – indeed, melodrama – but is peripheral to the main storyline, which is a detailed narrative of the Battle of Essling, imaginatively and movingly recreated by Rambaud after reading numerous contemporary accounts. Napoleonic warfare appears in all its utter brutality and horror: the mistreatment of civilians (looting, murder, rape), the callous killing of prisoners of war taken in the field, the tens of thousands of men mowed down by bullets and cannonballs or gutted by bayonets, the mass amputations carried out without anesthetic on the wounded, and the suicides by soldiers pushed to their limits and simply unable to bear it any longer. Napoleon coldly presides over it all, with a “blank, indifferent expression [that] only became passionate when he was angry” (p. 4). This, by the way, is contrary to Balzac’s intention, which was never to show the Emperor.

The Battle gets its title and theme from Balzac, who never carried through on his plan to write a novel on the two-day Battle of Essling (21-22 May 1809). Balzac intended to focus exclusively on the experience of battle: “only cannon, horses, two armies, uniforms. On the first page, the cannon roars; on the last it falls silent.”[2] Rambaud’s version is somewhat different. It centers on the experiences of Louis-François Lejeune (1775-1848), a painter and staff officer who really lived and fought under Napoleon and who left memoirs, but Rambaud fleshes out the story with numerous other characters, both real and invented. Thus, Rambaud’s Lejeune carries on a love affair with a young woman who turns out to be an Austrian spy. He is also close friends with Henri Beyle (the future Stendhal, who actually was in Vienna at the time). In the novel, Beyle happens to share lodgings with Friedrich Staps, the fanatical German student who tried to assassinate Napoleon in October 1809, an event that Rambaud moves forward to May. All this adds drama – indeed, melodrama – but is peripheral to the main storyline, which is a detailed narrative of the Battle of Essling, imaginatively and movingly recreated by Rambaud after reading numerous contemporary accounts. Napoleonic warfare appears in all its utter brutality and horror: the mistreatment of civilians (looting, murder, rape), the callous killing of prisoners of war taken in the field, the tens of thousands of men mowed down by bullets and cannonballs or gutted by bayonets, the mass amputations carried out without anesthetic on the wounded, and the suicides by soldiers pushed to their limits and simply unable to bear it any longer. Napoleon coldly presides over it all, with a “blank, indifferent expression [that] only became passionate when he was angry” (p. 4). This, by the way, is contrary to Balzac’s intention, which was never to show the Emperor.

Rambaud sees the Napoleonic Empire as overextended and already in decline by 1809. Essling was Napoleon’s first significant setback, although he went on to win convincingly at Wagram in July. For Rimbaud, the Battle of Essling exemplified a new sort of war; he has Napoleon muse at one point: “[W]ar was changing. As under the monarchies, battles were now played out between rival artilleries and rival regiments, with masses of troops launched against other masses – always more men, more dead, more canister shot and musketry” (p. 205-206). Moreover, revolutionary enthusiasm had waned and national sentiment was beginning to change camps, as a brigadier bluntly tells Marshal Lannes: “Of course an army with a soul is bound to win out against mercenaries! But where are today’s mercenaries? And what side are the patriots on? I’ll tell you: the patriots are rising up in arms against us in Tyrol, in Andalucia, in Austria, in Bohemia, and they will soon do the same in Germany and Russia…” (p. 140). This is perhaps an overly perspicacious and farsighted comment for an imperial officer to make in 1809, but it is true that Napoleon’s failure to appreciate the depth of popular opposition to French hegemony eventually led him into disaster. If nothing else, Staps’ last words before the firing squad in October 1809 – “Long live liberty! Long live Germany!” – ought to have warned him that there was a new mood growing in Europe. And so Napoleon blundered into the Russian campaign of 1812, a war against Alexander I, no doubt, but even more a war to the death with the Russian people.

The Retreat, Rambaud’s sequel to The Battle, covers this debacle, beginning with the occupation of Moscow and the inferno that devours the city. Rambaud prepared himself by reading most of the accounts by French participants for “images, scenes and details,” while “discard[ing] the author’s judgements and retain[ing] the colour” (p. 316, “Historical Notes”). There is perhaps no better or more thorough account of the terrible chaos of the slow withdrawal across the Russian vastness by a disintegrating and harassed army accompanied by a throng of terrified French civilians. Again, although Rambaud invented some of his characters, including his two principals, Captain François d’Herbigny and Sebastien Roque (one of Napoleon’s scribes), most of the others were real people, and all the incidents recounted apparently derive from historical sources. Leaving aside its literary qualities, the book constitutes an anthology of the horrors, terrors and cruelties of the Russian campaign.

The Retreat, Rambaud’s sequel to The Battle, covers this debacle, beginning with the occupation of Moscow and the inferno that devours the city. Rambaud prepared himself by reading most of the accounts by French participants for “images, scenes and details,” while “discard[ing] the author’s judgements and retain[ing] the colour” (p. 316, “Historical Notes”). There is perhaps no better or more thorough account of the terrible chaos of the slow withdrawal across the Russian vastness by a disintegrating and harassed army accompanied by a throng of terrified French civilians. Again, although Rambaud invented some of his characters, including his two principals, Captain François d’Herbigny and Sebastien Roque (one of Napoleon’s scribes), most of the others were real people, and all the incidents recounted apparently derive from historical sources. Leaving aside its literary qualities, the book constitutes an anthology of the horrors, terrors and cruelties of the Russian campaign.

Students (and teachers!) will certainly enjoy either or both of these books. The Battle, in particular, is likely to inspire class discussion on the nature of Napoleonic warfare, especially if used in conjunction with David Bell’s The First Total War.[3] The Retreat offers a case study of how a misconceived and ill-planned military campaign can lead only to catastrophe and suffering for both invader and invaded. In contrast, Napoleon’s Exile, the third volume in Rambaud’s trilogy, is less entertaining, less informative and certainly less useful in the classroom, even though it covers a period of the Napoleonic saga generally neglected by novelists and historians alike. Having written two novels about how endless and ever-expanding warfare undermined the First Empire, Rambaud decided to write about the political collapse of 1814-1815.

Napoleon’s Exile opens with the Allied occupation of Paris and the Bourbon Restoration of April 1814 and ends with Napoleon’s landing back in France on 1 March 1815; Waterloo, the final military defeat, still lies, unmentioned, in the future. This time, the fallen Emperor is the story’s primary focus, and the novel consequently has a far different tone from its predecessors. Rambaud puts this difference in cinematic terms, describing this third novel as “less stereoscopic-color [moins scope-couleurs] than the other two.”[4] Rather than the clash of battle or the whimpering of the dying, the reader hears the hushed whispers of intrigue, as royalist activists, Parisian politicians, European diplomats, and, of course, Napoleon himself plot and maneuver for advantage. The investigations and activities of the fictional Octave Sénécal, a secret agent in Napoleon’s service, provide the thread that ties the parts together.

Napoleon’s Exile opens with the Allied occupation of Paris and the Bourbon Restoration of April 1814 and ends with Napoleon’s landing back in France on 1 March 1815; Waterloo, the final military defeat, still lies, unmentioned, in the future. This time, the fallen Emperor is the story’s primary focus, and the novel consequently has a far different tone from its predecessors. Rambaud puts this difference in cinematic terms, describing this third novel as “less stereoscopic-color [moins scope-couleurs] than the other two.”[4] Rather than the clash of battle or the whimpering of the dying, the reader hears the hushed whispers of intrigue, as royalist activists, Parisian politicians, European diplomats, and, of course, Napoleon himself plot and maneuver for advantage. The investigations and activities of the fictional Octave Sénécal, a secret agent in Napoleon’s service, provide the thread that ties the parts together.

Napoleon is omnipresent in all three volumes, but what the author thinks of him is never made explicit. In an interview given seven years ago, Rambaud hedged: “Frankly, I have no point of view [on Napoleon]. And the more it goes on, the less of one I have. […] I don’t want to demonstrate anything, I’m only trying to show him as he was according to the people who knew him.”[5] In The Battle, Napoleon is a cold demigod, “his face as smooth and expressionless as an unfinished statue” (p. 205). Only once in this novel does Rambaud peer into Napoleon’s mind to reveal an Emperor cynical and entirely lucid about his officers and himself: “They all hate me! […] They feign loyalty, but the only reason they march is to amass gold, titles, chateaux and women! They hate me and I love nobody. […] I know that a force drives me and nothing can restrain it. I must proceed, in spite of myself and against the rest of them” (pp. 127-128). In The Retreat, we see a Napoleon who has begun his physical decline and who is even delusional in assessing the Russian situation, but who is still dominated by a strong authoritarian streak – “He loved power, not men, with an artist’s love, as a musician loves his violin” – and, above all, inexorably driven forward by an overweening sense of his own historic role: “The Emperor believed in nothing anymore except destiny. Everything was written.” Napoleon’s Exile reveals a less imperious Napoleon. In Rambaud’s words, “we get closer to the fellow, because it’s the only period of his life where he is human. He’s afraid, he cries, he attempts suicide.”[6] Napoleon finally emerges as a full character with both dark and light sides. The novel depicts his contempt for the populace, his hatred of the mob, his cowardice in the face of royalist demonstrators, and his egotistical scheming for a return to power; however, it also portrays a gentler and even playful Napoleon, a tireless administrator – “the Emperor began talking about transforming [Elba], building real roads, sewers in the towns” (p. 214) – and an inveterate charmer of men.

Grove Press deserves our thanks for publishing these English versions of the original novels. It is unfortunate, however, that in two instances the cover designs, though attractive, are anachronistic and do not reflect the book’s contents.[7] And while Will Hobson’s translation of the first two volumes is excellent, Shaun Whiteside’s version of L’Absent is rife with errors due to sloppiness, failure to understand the original French and/or lack of knowledge of the historical context.[8]

1. Éditions Grasset & Fasquelle published the original French novels, all of which are now available from Livre du Poche.

2. Balzac to Mme Hanska, 1833, quoted in “Historical Note,” The Battle, p. 298.

3. David A. Bell, The First Total War: Napoleon’s Europe and the Birth of Warfare as We Know It (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007).

4. “Entretien: Patrick Rambaud,” L’Express, 1 Sept. 2003.

5. “Entretien.”

6. “Entretien.”

7. The cover of The Battle shows David’s “Napoleon Crossing the Alps” (an event that occurred in 1800), while The Retreat uses Meissonier’s “Napoleon on Campaign in 1814.”

8. The many minor, but nonetheless irritating, errors include: “Faubourg de la Conférence” for “Barrière de la Conférence” (p. 37), “Police Chief” for “capitaine de la gendarmerie” (p. 146), “Pluto” for “Plutarque” (p. 241), and “camp marshal” (instead of brigadier) for “maréchal de camp” (p. 336). Somehow “l’établissement des bains […] avec ses deux cents baignoires à trente sous” becomes “the public baths – which offered tubs at 230 sous” (p. 70), while a letter tossed “sur la cheminée” in French is thrown “in the fire” in English (p. 77), only to be read a few minutes afterwards! Worst of all, Napoleon’s comment that “s’ils [les Bourbons] ne soutiennent pas ces manufactures que j’ai créés, ils seront chassés dans six mois!” is rendered as: “they can’t bear those factories I’ve set up; they’ll be driven out in six months!” (p. 177).

Patrick Rambaud, The Battle, trans. Will Hobson. New York: Grove Press, 2000, 320 pp.; The Retreat, trans. by Will Hobson. New York: Grove Press, 2004, 336 pp.; Napoleon’s Exile, trans. by Shaun Whiteside. New York: Grove Press, 2006, 352 pp.