Daniel A. Gordon

Edge Hill University

Despite May 1968’s celebrated impact on French cinema, the field of films about it available for use in the French history seminar room is surprisingly weak. If for the sake of argument we exclude films made around 1968 themselves, and restrict ourselves to films made in the twenty-first century, purporting to provide historical treatment, and obtainable on DVD with English subtitles, a problem immediately becomes apparent. Namely that virtually all available options tend to reinforce precisely the view that the last twenty years of historiography has been trying to dismantle: that ‘68 was only about students, only took place on the Left Bank, and was not really about politics. Thus Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers (2003) has rightly been damned for its parade of misleading stereotypes. Only the opening scene at the February 1968 protests against the dismissal of Henri Langlois as director of the Cinémathèque française gives any adequate sense of the issues at stake. The obsessive focus on the sex lives of indulgent bourgeois youth simply evades the politics of the time. Philippe Garrel’s Les amants réguliers (2005) is better, giving some insight into the atmosphere of the Night of the Barricades and the post-May personal dilemmas of its Latin Quarter participants. But this three-hour film whose central character actually falls asleep on the barricades is far too languid to keep the attention of most modern Anglo-Saxon audiences.[1] Olivier Ducastel and Jacques Martineau’s more accessible, but no less lengthy, Nés en 68 (2008) was for me a film of two halves. It starts as a horribly cliché-laden lightweight romp through the standard student ’68 and post-’68 free love in a commune in the Lot, that feels like the made-for-TV fare it is.[2] Only after leaving les années 68 does Nés en 68 become a multigenerational drama of somewhat greater depth, tackling 1990s AIDS and sans-papiers activism and death, before finally, in an explicit attack on Nicolas Sarkozy’s 2007 “liquidate the heritage of May ‘68” speech, affirming the longevity of the political heritage of 1968 – the very values that were treated in such a sloppy manner in the first half of the film.

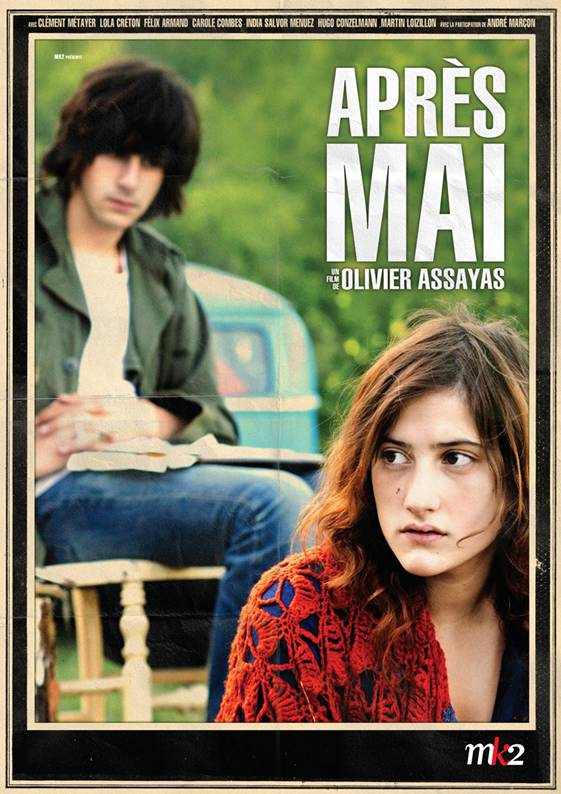

In such a context, one can only welcome Olivier Assayas’ Après mai ‘s DVD release. For Assayas has positioned his film as a challenge to dominant generalisations about 1968.[3] In this attempt at differentiation he arguably succeeds in many respects, but is less successful in others. The most obvious difference is in terms of generational chronology, signposted in the film’s French title. For Assayas’ chief innovation lies in deciding to make a film about a set of phenomena which memorial shorthand thinks of as ‘May 1968’, yet start it some three years after May.[4] A few years’ gap means a great deal in one’s adolescence. Whereas the foot-soldiers of ’68 are classically depicted as immediate postwar babyboomers, aged around 20 in 1968 – and it is well known that their leaders were older than that – the heroes of this film are the lycéens of 1971, born in the mid-1950s. This is Assayas’s own generation (he was born in 1955), and he has good grounds for complaining of their relative marginalisation, since the narrative of ’68 remains in important respects monopolized by their elders. Assayas’ film thus points in the same direction as recent historiography, which has tended to broaden out discussion to les années 68.[5] The lycée student movement of 1971, which forms the backbone of the film, was ignited by the prison sentence handed out to Gilles Guiot, a pupil at Paris’ Lycée Chaptal, and resulted in the politicisation of Après mai’s teenage protagonists. It has been overlooked even compared to the lycéens movement of May ‘68, which itself plays second fiddle historiographically.[6]

In such a context, one can only welcome Olivier Assayas’ Après mai ‘s DVD release. For Assayas has positioned his film as a challenge to dominant generalisations about 1968.[3] In this attempt at differentiation he arguably succeeds in many respects, but is less successful in others. The most obvious difference is in terms of generational chronology, signposted in the film’s French title. For Assayas’ chief innovation lies in deciding to make a film about a set of phenomena which memorial shorthand thinks of as ‘May 1968’, yet start it some three years after May.[4] A few years’ gap means a great deal in one’s adolescence. Whereas the foot-soldiers of ’68 are classically depicted as immediate postwar babyboomers, aged around 20 in 1968 – and it is well known that their leaders were older than that – the heroes of this film are the lycéens of 1971, born in the mid-1950s. This is Assayas’s own generation (he was born in 1955), and he has good grounds for complaining of their relative marginalisation, since the narrative of ’68 remains in important respects monopolized by their elders. Assayas’ film thus points in the same direction as recent historiography, which has tended to broaden out discussion to les années 68.[5] The lycée student movement of 1971, which forms the backbone of the film, was ignited by the prison sentence handed out to Gilles Guiot, a pupil at Paris’ Lycée Chaptal, and resulted in the politicisation of Après mai’s teenage protagonists. It has been overlooked even compared to the lycéens movement of May ‘68, which itself plays second fiddle historiographically.[6]

The 17-year-olds of the early Seventies are an important group because their long-term cultural and political outlook, as evidenced by voting behaviour even decades afterwards, suggests that the group most influenced by left-libertarian values were children in ’68, more in fact than the generation politically active then.[7] This paradox is fairly easy to explain in terms of the percolation of social change over time: attitudes held in one generation by a pioneering avant-garde can quickly become the taken-for-granted assumptions of larger swathes of the next age cohort. The film is good at portraying mini-generation gaps. For example a thirty-something leftist militant – who, we can surmise from the posters on the wall and the fact that his group has an office which it allows other factions to use, must be a member of the Parti socialiste unifié – rebukes the film’s protagonist Gilles for making a sexually explicit poster.

So Assayas has, unlike some directors of films about ’68, clearly done his homework. His careful attention to period detail means that the film quite accurately captures the situation in 1971 (or rather, that part of the situation in 1971 experienced by people like Assayas). An historian watching a fictionalised film set in ‘their period’ will always be on the lookout for anachronisms, but these were far harder to spot in Après mai than in, say, Nés en 68. Was coffee really served in cardboard cups on Italian trains in 1971? Are the characters’ shirts and sheets too crisply ironed for what were supposed to be hippies? On more substantive issues, there is little to object to historically. Après mai had a reasonable arthouse distribution in the UK. I first saw it at Manchester’s Cornerhouse with two people who had been young and gauchiste in France around the time, and they found it broadly accurate. For Assayas clearly resists the tendency in other recent films about ’68 to homogenise activism. As he explained in an interview, the principal motivation for making the film[8] was to differentiate rival gauchiste groupuscules.

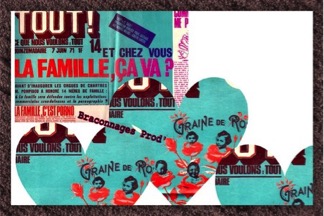

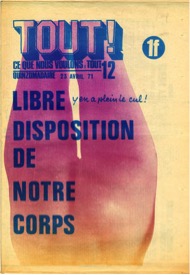

In particular, the focus of the film and Assayas’ own sympathies lie clearly with Vive la Révolution, the libertarian breakaway from the Maoist Gauche prolétarienne. While VLR is less central to dominant French narratives than the GP, it has received some attention in scholarship because of its pivotal place at precisely the uneasy intersection of radical left politics and counterculture explored in this film.[9] Such scholarship has focused more on the agency of VLR’s somewhat older founders such as Roland Castro, so the film is refreshing in presenting the perspective of the movement’s teenage footsoldiers. Gilles sells real issues of VLR’s ostentatiously countercultural paper Tout! outside his school gates, capturing the brief moment in 1970-71 when Tout! seemed poised to become a kind of France-Soir rouge with as many as 100,000 readers, its print run peaking with the issue Gilles sells, that called for the dissolution of the CRS’ Brigades spéciales.[10]

Gilles also buys counterculture papers at street newsstands, emphasising the importance of the dissemination of the alternative press via the Nouvelles messageries de la presse parisienne [11] – a system economically under threat today – as one of the few methods Seventies youth had of accessing ideas outside the mainstream. We also get a visual sense of the mechanics of leaflet reproduction. And the dialogue captures the workerist language that animated debates among mainly middle-class activists: at the height of what Daniel Bensaïd called the “religious cult of the red proletarian,”[12] what will appeal to the workers is deemed of utmost importance, even if actual workers are thin on the ground. Despite its openness to counterculture, the Ligue communiste remained closer to traditional Marxism than the ultra-libertarians of VLR [13] – but both groups are correctly depicted as part of an overlapping, fluid youth milieu.

Gilles also buys counterculture papers at street newsstands, emphasising the importance of the dissemination of the alternative press via the Nouvelles messageries de la presse parisienne [11] – a system economically under threat today – as one of the few methods Seventies youth had of accessing ideas outside the mainstream. We also get a visual sense of the mechanics of leaflet reproduction. And the dialogue captures the workerist language that animated debates among mainly middle-class activists: at the height of what Daniel Bensaïd called the “religious cult of the red proletarian,”[12] what will appeal to the workers is deemed of utmost importance, even if actual workers are thin on the ground. Despite its openness to counterculture, the Ligue communiste remained closer to traditional Marxism than the ultra-libertarians of VLR [13] – but both groups are correctly depicted as part of an overlapping, fluid youth milieu.

Yet while the detail is very 1971, some of the general attitudes are more timeless. It is likely that many viewers who have been young and with vaguely countercultural aspirations at almost any point in the last 50 years will recognise here something of their own experience, or perhaps their dreams of what they wanted their youth to resemble. But perhaps this is because one gets the sense from Après mai’s characters that they were the first generation to go through teenage rebellion in stylistically ritualised fashion, following a script already laid down, to be endlessly repeated as tragedy or, more often, farce.

This is borne out by the strange mixture of brutality and leniency we see in the authorities’ interaction with the film’s youth. The Brigades spéciales that we see in an attention-grabbing early scene at a demonstration at the Place Clichy on 9 February 1971, are, correctly, depicted as a muscular and militarised force – beating young protesters already on the ground, and firing off their bazooka-like tear gas canister launchers. For any students today who have not experienced police brutality first hand, this scene immediately conveys what the protesters of 1971 were up against. Hence they wear the crash helmets adopted in 1968 as practical protection, while yelling “CRS-SS” at the police who, given the Raymond Marcellin-era Interior Ministry’s propensity to throw money at them to prepare them for a potential new May ’68, are themselves also repeating lines learned in May. Yet as in so many international instances around 1968, the behaviour of special police units and their presumption of impunity only pushes the protesters into escalation. The photographic image of Richard Deshayes, the VLR activist blinded in one eye by an exploding tear gas canister on this occasion, appears more than once on posters in the film, as in real life, as a powerful symbol of Pompidolian France’s repression of youth.

Parents, by contrast, are conspicuous by their absence. What might strike young people today as peculiar is the comparatively hands-off role parents played in the lives of their offspring, and the latter’s sense of limitless freedom. What little we see of the parents – our hero lunching with his father at work – implies that they were not, drug-use aside, overly concerned with what their offspring were doing: it was just a phase. One gets a similar sense from the headmaster who calls in one of the pupils suspected of daubing slogans and posters on school buildings: he goes through the motions of condemning vandalism, while emphasising that he does not want Jean-Pierre to inform on his co-conspirators. The headteacher thus personifies what Arthur Marwick termed “measured judgement.”[14] Yet there is little measured judgement in the 17-year-olds’ riposte, as they attack security guards with Molotov cocktails, leaving one of the guards in a coma. The activists do not seem much concerned about the ethical consequences, beyond the opportunity provided to enact their fantasies of going underground. At one point they burn an empty car – the kind of activity that the Italian Red Brigades engaged in before upgrading to more deadly violence (unlike the characters in this film).[15] Such elements might spark an interesting classroom discussion about the relationship between 1968 and political violence, given that the film’s characters seem to suffer no serious repercussions for behaviour that today would probably be treated with greater severity.

One might suggest that narcissistic irresponsibility is an occupational hazard of youth. Yet the mature Assayas has enough self-awareness to depict Gilles as a flawed, self-doubting, autobiographical character, in whom tensions between radical politics and individual self-discovery are interestingly played out. Gilles is clearly idealistic and more likeable than many of his associates, but rather self-centred. For Gilles, who like the young Assayas is a painter,[16] art comes first, before political struggle, before his girlfriends, and before his family: he appears too self-absorbed to display much emotion when his father talks about having Parkinson’s. Assayas has sufficient breadth of vision, though, to acknowledge the different choices made by members of his own generation. Gilles is rebuked for being too distant from real life by a more conventionally political ally, Jean-Pierre, one of many characters who seem more like cardboard cut-out activists. Tellingly, Jean-Pierre is a member of the Ligue communiste, who comes to distance himself from it out of admiration for the ‘‘new resistance’’ claims and confrontational tactics of the Gauche prolétarienne and its armed wing the Nouvelle résistance populaire. This mirrors Assayas’ own ideological trajectory: influenced by his parents’ anti-Stalinist ideas (his mother was a refugee from the Communist takeover of Hungary, while his father knew Victor Serge), and Situationism, Assayas perceived the Trotskyism and Maoism of his contemporaries as too close to Communism.[17]

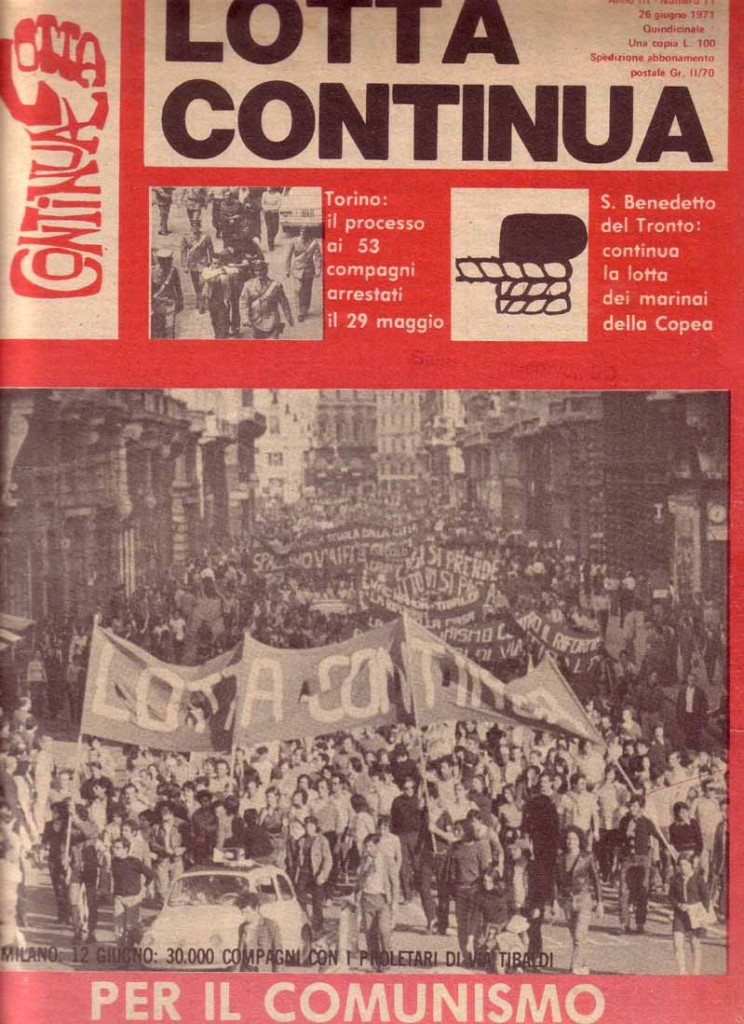

Another departure from standard ’68 narratives is geographical. Although the DVD front-cover blurb from Time Out describes Après mai as ‘‘A freewheeling tale of sex, drugs and heartache in 1970s Paris,’’ it is actually refreshing to have a film about les années 68 mostly set outside Paris proper. Assayas went to school in ‘‘a high school in suburban Paris, which was basically the countryside’’[18] – tractors can actually be spotted at one point – and this translates into a tale of small-town suburban rebels, close enough to Paris to get to demonstrations but dependent on trains, scooters and hitchhiking to do so. The most they can do locally to challenge authority is to daub slogans on their own lycée. Public transport features frequently, not only as a method of getting from A to B, but as a time for reading when Gilles catches up on counterculture magazines, Situationist texts and criticisms of Maoist China. Later on they gravitate towards Paris, but the locations used – like a commune in Kremlin-Bicêtre accessed by bike – seem deliberately located to emphasise their distance. This seems a more accurate depiction of the lives of rank-and-file soixante-huitards than presumptions that that they all slept within a stone’s throw of the Boulevard St. Michel. For a significant portion of the film, the protagonists leave the Paris region altogether, first for the Midi and then for Italy, again accurately capturing the connections between VLR and the Italian group Lotta Continua, from which, as Manus McGrogan has shown, Tout! derived its name.[19] This may also be a journey in search of Assayas’ own roots, since his father was an Italian antifascist, and Assayas himself went to Florence in the early Seventies [20]. Transnationalism is thus as much of a trend for Assayas as it is for current scholarship on ’68. The hippy trail to Afghanistan, the wars in Vietnam and Laos, and struggles in Latin America are alluded to, but from the point of view of European youth. The global South forms an imagined community of solidarity, a backdrop to the lives of western hippy/leftists.

Another departure from standard ’68 narratives is geographical. Although the DVD front-cover blurb from Time Out describes Après mai as ‘‘A freewheeling tale of sex, drugs and heartache in 1970s Paris,’’ it is actually refreshing to have a film about les années 68 mostly set outside Paris proper. Assayas went to school in ‘‘a high school in suburban Paris, which was basically the countryside’’[18] – tractors can actually be spotted at one point – and this translates into a tale of small-town suburban rebels, close enough to Paris to get to demonstrations but dependent on trains, scooters and hitchhiking to do so. The most they can do locally to challenge authority is to daub slogans on their own lycée. Public transport features frequently, not only as a method of getting from A to B, but as a time for reading when Gilles catches up on counterculture magazines, Situationist texts and criticisms of Maoist China. Later on they gravitate towards Paris, but the locations used – like a commune in Kremlin-Bicêtre accessed by bike – seem deliberately located to emphasise their distance. This seems a more accurate depiction of the lives of rank-and-file soixante-huitards than presumptions that that they all slept within a stone’s throw of the Boulevard St. Michel. For a significant portion of the film, the protagonists leave the Paris region altogether, first for the Midi and then for Italy, again accurately capturing the connections between VLR and the Italian group Lotta Continua, from which, as Manus McGrogan has shown, Tout! derived its name.[19] This may also be a journey in search of Assayas’ own roots, since his father was an Italian antifascist, and Assayas himself went to Florence in the early Seventies [20]. Transnationalism is thus as much of a trend for Assayas as it is for current scholarship on ’68. The hippy trail to Afghanistan, the wars in Vietnam and Laos, and struggles in Latin America are alluded to, but from the point of view of European youth. The global South forms an imagined community of solidarity, a backdrop to the lives of western hippy/leftists.

Moreover, what clearly dates this as 1971 rather than 1968 is the omnipresence of Anglo-American pop culture. Whereas in 1968 even the most politically rebellious French youth dressed in very “square” fashion by the standards of their Anglo-Saxon contemporaries, the French teenagers of this film look positively Californian. American characters feature prominently: the relationship begun in Italy between Leslie, an American Eastern dance enthusiast, and Gilles’ comrade Alain, symbolises this meeting of minds. French pop music is almost totally absent, while Gilles has everyone from the Byrds to the MC5 in his record collection. Looking for an international market, films on Europe in the Sixties sometimes use more anglophone material than was the case at the time. Yet the early Seventies arguably did mark a turning point. 1971 was the year that the Rolling Stones recorded Exile in Main Street while living in tax exile in Villefranche-sur-Mer, and the year after thousands of French hippies descended on the Isle of Wight Festival to hear Jimi Hendrix. This was no longer the world of Salut les copains!.

Moreover, what clearly dates this as 1971 rather than 1968 is the omnipresence of Anglo-American pop culture. Whereas in 1968 even the most politically rebellious French youth dressed in very “square” fashion by the standards of their Anglo-Saxon contemporaries, the French teenagers of this film look positively Californian. American characters feature prominently: the relationship begun in Italy between Leslie, an American Eastern dance enthusiast, and Gilles’ comrade Alain, symbolises this meeting of minds. French pop music is almost totally absent, while Gilles has everyone from the Byrds to the MC5 in his record collection. Looking for an international market, films on Europe in the Sixties sometimes use more anglophone material than was the case at the time. Yet the early Seventies arguably did mark a turning point. 1971 was the year that the Rolling Stones recorded Exile in Main Street while living in tax exile in Villefranche-sur-Mer, and the year after thousands of French hippies descended on the Isle of Wight Festival to hear Jimi Hendrix. This was no longer the world of Salut les copains!.

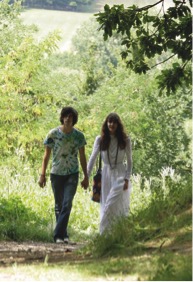

Here again Assayas’ attention to detail is nuanced. In contrast to Nés en 68’s over-obvious use of Street Fighting Man, Après mai’s soundtrack uses the dreamier side of British “progressive rock” typified by Pink Floyd and Soft Machine. Reflecting Assayas’ interest in pastoral neo-ruralism,[21] Gilles and his first girlfriend Laure flounce around the woods of the Ile-de-France as if they were Syd Barrett Et al on Cambridge’s Grantchester Meadows. This reterritorialisation of ostensibly very English sounds is not inaccurate, for the Floyd’s philosophical pretensions were sometimes better appreciated abroad, they making it onto French television as early as February 1968.[22] Laure not only moves to London but has a stepfather who is a roadie for Soft Machine, whose Why Are We Sleeping? is one of the soundtrack’s most memorable parts. Soft Machine’s Kevin Ayers, himself a longterm resident of a village near Carcassonne, was often described as ‘louche’,[23] an epithet that might equally be applied to some of the characters in Après mai. Gilles himself moves to London to train at Pinewood Studios on a dire film about Nazis, dinosaurs and scantily clad cavewomen, reminding us what in mainstream Seventies popular culture needed countering.

Here again Assayas’ attention to detail is nuanced. In contrast to Nés en 68’s over-obvious use of Street Fighting Man, Après mai’s soundtrack uses the dreamier side of British “progressive rock” typified by Pink Floyd and Soft Machine. Reflecting Assayas’ interest in pastoral neo-ruralism,[21] Gilles and his first girlfriend Laure flounce around the woods of the Ile-de-France as if they were Syd Barrett Et al on Cambridge’s Grantchester Meadows. This reterritorialisation of ostensibly very English sounds is not inaccurate, for the Floyd’s philosophical pretensions were sometimes better appreciated abroad, they making it onto French television as early as February 1968.[22] Laure not only moves to London but has a stepfather who is a roadie for Soft Machine, whose Why Are We Sleeping? is one of the soundtrack’s most memorable parts. Soft Machine’s Kevin Ayers, himself a longterm resident of a village near Carcassonne, was often described as ‘louche’,[23] an epithet that might equally be applied to some of the characters in Après mai. Gilles himself moves to London to train at Pinewood Studios on a dire film about Nazis, dinosaurs and scantily clad cavewomen, reminding us what in mainstream Seventies popular culture needed countering.

Nevertheless, the social stratum depicted does not represent a great challenge to standard accounts. In Assayas’ own words describing one of his earlier films, this is ‘‘un film non pas sur les années 1970 mais sur des années 1970.’’[24] For despite its chronological and geographical broadening, this film – perhaps necessarily so given its heavily autobiographical inspiration – depicts the viewpoint of white male heterosexual youth of bourgeois origin and in post-compulsory education. With the exception, ironically, of their security guard enemy, we are still with the jeunesse dorée, albeit in its updated 1971 version. Gilles comes from a book-lined home, his father is a TV producer, and he is all set to attend the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. His comrades all have a place where they can lie low for the summer. How they come to party in some quite plush buildings is only explained once, as the largesse of Laure’s rich new boyfriend. In Florence, one of their American contacts is the daughter of a diplomat (and, it is alleged, CIA agent). There is thus some contradiction involved in their aspirations to be revolutionaries.[25] In interview Assayas falls back on the socially mixed nature of his lycée, and points out that, because of their mobile phones and computers, nowadays teenagers “seem rich” compared to his anti-consumerist generation. Yet in simultaneously suggesting that his contemporaries ‘‘functioned with basically no money,’’ yet spent what they had on ‘‘books, usually radical books, newspapers and coffee,’’[26] he may arguably simply be pointing to a different, bohemian culture of consumption. Gilles’ thirst for knowledge is such that at one point he buys four different newspapers – Combat, Parapluie, Actuel and J’accuse – from the same newsstand.

Whereas some VLR members were actively involved in the Front homosexuel d’action révolutionnaire and immigrant worker solidarity campaigns,[27] neither is mentioned directly. VLR activists like Nadja Ringhart and Françoise Picq also participated in the Mouvement de libération des femmes,[28] and in the film female activists are granted some voice and agency, albeit more limited than their male counterparts. The dilemma between what McGrogan terms ‘‘the festive, sensual May and the Marxist, party-and-class May’’[29] is personified in Gilles’ choice of girlfriends: Laure’s letters from London enthuse about counterculture, whereas Christine is a more serious activist, committed to a film collective. We are clearly in an era after sexual liberation, but before the full impact of second-wave feminism, the ‘‘scratch a hippy, find a sexist’’ world where hip and heterosexual young men were clear beneficiaries. There is much female toplessness, and Gilles paints a semi-naked Christine while she sleeps, at the risk of objectifying her.

However the sexual aspect (unlike The Dreamers or Nés en 68) is never allowed to overwhelm the political content, and is arguably necessary for realist autobiography. Romantic and erotic desire are often hard to separate from the intensity of early political experience. Many autobiographical accounts by male activists recognise the existence at times of ulterior motives.[30] Later in the film, a more critical perspective on gender emerges, in a telling episode when Christine unpacks the food shopping for her film collective / commune, only to overhear her male comrades having a self-important discussion about revolutionary strategy, consigning her in an afterthought to merely technical support. As Assayas has noted, “Le gauchisme était très macho,”[31] and this would play a crucial role in the development of women’s movements.

So Après mai is, in a problematic field, the least objectionable of recent options for a seminar room screening. Without especially profound revelation, this is nevertheless a well-made, engaging film that convincingly recreates the atmosphere of a certain sort of post-68 activism. Although, lacking strong plot development, it presents the typical difficulty of introducing French cinema to audiences used to less challenging fare, it manages to do so in more accessible doses than, for example, Les amants réguliers. Students would probably need to come to the film with some previous knowledge in order to spot the contemporary references, but it certainly offers a stimulating starting point for discussion. In the words of the teacher introducing his class to a seventeenth-century text by Blaise Pascal in Après mai’s opening scene, ‘‘Don’t balk at the phrasing. It’s from another era. Then you’ll tell me what it reminds you of in today’s terms.”

Olivier Assayas, Director, Après mai [Something in the Air], 2012, Color, 122 min, France, MK2 Productions, France 3 Cinéma, Vortex Sutra.

- See James S. Williams, ‘‘Performing the Revolution,’’ in Julian Jackson, Anna-Louise Milne and James S. Williams, eds, May ’68: Rethinking France’s Last Revolution (Palgrave, 2011), pp. 280-298.

- See Chris Reynolds, Memories of May ’68: France’s Convenient Consensus (Cardiff University Press, 2011), pp. 129-130.

- See Richard Porton, ‘‘Portrait of the Artist as a Young Radical: An Interview with Olivier Assayas,’’ Cineaste, vol 38, no 2 (Spring 2013), pp. 8-12.

- Indeed, this is Assayas’ third historical drama set in the Seventies, following his 1994 film L’Eau froide, and his 2010 biopic Carlos.

- For example, Gerd-Rainer Horn, The Spirit of ’68: Rebellion in Western Europe and North America, 1956-1976 (Oxford University Press, 2007); Philippe Artières and Michelle Zancarini-Fournel, eds, 68: Une histoire collective [1962-1981] (La Découverte, 2008).

- Didier Leschi, ‘‘Mai 1968 et le movement lycéen,’’ Matériaux pour l’histoire de notre temps, no 11 (1988), pp. 260-264; Chris Warne, ‘‘Misreading Youth Activism in 1970s France: the Case of the Lycéens Against la loi Debré’,” paper to The Utopian Years? Radical Left Movements in the France of Pompidou Conference, University of Portsmouth, 11 May 2011.

- Daniel A. Gordon, ‘‘Liquidating May ’68? Generational Trajectories of the 2007 Presidential Candidates,’’ Modern and Contemporary France, vol 16, no 2 (May 2008), pp. 143-159.

- Porton, ‘‘Portrait of the Artist,” p. 9.

- A.Belden Fields, Trotskyism and Maoism: Theory and Practice in France and the United States (Praeger, 1988), pp. 100-101; Christophe Bourseiller, Les maoïstes: la folle histoire des gardes rouges françaises (Plon 1996); Manus McGrogan, ‘‘Tout! in Context, 1968-1973: French Radical Press at the Crossroads of Far Left, New Movements and Counterculture,’’ PhD thesis, University of Portsmouth, 2010; Manus McGrogan, ‘‘Vive La Révolution and the Example of Lotta Continua: the Circulation of Ideas and Practices Between the Left Militant Worlds of France and Italy After 1968,’’ Modern and Contemporary France, vol. 18, no. 3 (August 2010), pp. 309-328; Daniel A. Gordon, Immigrants and Intellectuals: May ’68 and the Rise of Anti-Racism in France (Merlin Press, 2012), pp. 99-100, 103-107.

- McGrogan, ‘‘Tout! in Context,’’ pp. 88, 94.

- McGrogan, ‘‘Tout! in Context,’’ p. 93.

- Daniel Bensaïd, Une lente impatience (Stock, 2004).

- Jean-Paul Salles, La Ligue communiste révolutionnaire (1968-1981). (Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2005).

- Arthur Marwick, The Sixties: Cultural Revolution in Britain, France, Italy and the United States, c.1958- c.1974 (Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 13.

- Renato Curcio, A visage découverte (Lieu commun, 1993).

- Brian Price and Meghan Sutherland, ‘‘On Debord, Then and Now: An Interview with Olivier Assayas,’’ World Picture Journal, no. 1 (Spring 2008), p. 3.

- Price and Sutherland, ‘‘On Debord,’’ pp. 1-6.

- Porton, ‘‘Portrait of the Artist,’’ p. 12.

- McGrogan, ‘‘Vive La Révolution.’’

- Price and Sutherland, ‘‘On Debord,’’ p. 1; The Making of Something In The Air, extra on DVD of Après mai.

- Laura Tuillier, ‘‘Après mai: rencontre avec Olivier Assayas,’’ Trois Couleurs, no 106 (November 2012), p. 40.

- ‘‘Pink Floyd – Astronomy Domine – Bouton Rouge French TV ORFT, [sic], http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ijYN8typAA0, accessed 6 October 2014.

- For example, The Times, 21 February 2013.

- Tuillier, ‘‘Rencontre avec Olivier Assayas,’’ p. 38.

- Cf the Oxford academics’ rebellious offspring described in Thin He Was And Filthy Haired: Memoirs of a Bad Boy (Penguin 1996), the Red Dwarf actor Robert Llewellyn’s autobiographical account of early 1970s English counterculture.

- Porton, ‘‘Portrait of the Artist,’’ p. 12.

- Julian Bourg, From Revolution to Ethics: May 1968 and Contemporary French Thought (McGill-Queens University Press, 2007), p. 187; Gordon, Immigrants and Intellectuals, pp. 99-100, 103-107.

- Hervé Hamon and Patrick Rotman, Génération. 2. Les années de poudre (Seuil, 1988), pp. 195-241, 312-339, 439-454.

- McGrogan, ‘‘Tout! in Context,’’ p. 50.

- For example, Benjamin Stora, La dernière génération d’octobre (Stock, 2003), p. 40.

- Tuillier, ‘‘Rencontre avec Olivier Assayas,’’ p. 41.