Adam Watt

University of Exeter, UK

Proust crops up in some intriguing places. In the third season of The Sopranos Dr. Melfi discusses involuntary memory with Tony during therapy. Richard E. Goodkin (among others) has written about the links between Proust and Hitchcock’s Vertigo.[1] How many readers of FFFH, I wonder, whilst watching Spectre, the most recent James Bond film, found themselves indulging a smug smile upon learning that the psychologist whom Bond tracks down to a private clinic in the Alps is called Madeleine Swann? Those who really know their Proust may also have nodded sagely at the villain Oberhauser later goading the hero that “Of course, the faces of your women are interchangeable, aren’t they, James?” a line echoing the remark by Proust’s narrator in Un amour de Swann, that for some men (misogynists, that is, like Swann and James Bond), women represent “les instruments interchangeables d’un plaisir toujours identique.”[2] In popular television and on the big screen, Proust’s cultural value remains high. Beyond the cultish tracing and collecting of passing references, however, those interested in Proust’s work and the socio-cultural context of Belle Epoque France from which it emerged also have a number of substantive screen adaptations they might turn to for more lasting sustenance.

Harold Pinter, as is well known, between 1972-73 wrote a screenplay based upon Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu. Although it was successfully adapted for the stage at the National Theatre in London in 2000, a film version has never been produced, for want of sufficient financial investment in the project. A number of partial adaptations of Proust’s novel have been made for the big screen, however, and to varying degrees of success. In 1984, the German director Volker Schlöndorff, fresh from Oscar- and Palme d’or success with his 1979 adaptation of Günter Grass’s The Tin Drum, released Swann in Love, an adaptation of the love story told in the second part of Du côté de chez Swann, the first volume of Proust’s great novel. Starring Jeremy Irons as Swann and Ornella Muti as Odette, Schlöndorff’s English-language heritage film is a handsome but somewhat stiff depiction of Swann’s jealous travails in late nineteenth-century Paris. As a stand-alone narrative told in the third person, Proust’s Un amour de Swann lends itself more readily to the screen than the vast expanses of first-person prose that surround it in A la recherche.

Fascinating adaptive takes on this material have nevertheless been forthcoming in recent years. Raoul Ruiz’s Le Temps retrouvé (1999) in fact draws more widely on other parts of Proust’s novel than its single-volume title would suggest. The film is a lavish, three-hour paean to Proust, to the fin-de-siècle and early twentieth-century French culture, to French film and its stars, as much as it is an adaptation of the culminating volume of A la recherche. Released the following year, Chantal Akerman’s La Captive is a drama associatively constructed from elements of La Prisonnière, the fifth volume of the Recherche, whose pages tell of the protagonist’s troubled and troubling co-existence in Paris with his beloved Albertine, whose flight from him is recounted in the partner volume that follows, Albertine disparue. While Schlöndorff and Ruiz are certainly useful and stimulating resources for students of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century France, Akerman’s film is a transposition as well as an adaptation (mobile phones and other indices of a form of modernity somewhat removed from Proust’s own make their mark on it), which is perhaps better left to students of film studies and those more familiar with the subtleties of the Albertine narrative.[3]

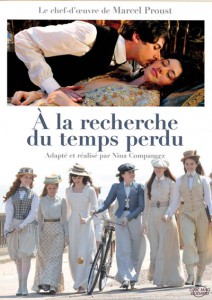

Now, however, Proust enthusiasts and students of early twentieth-century France have a further addition to the “Proust on Screen” catalogue to explore.[4] A la recherche du temps perdu was adapted for television and directed by Nina Companeez in 2011, the crowning accomplishment of a fifty-year career in film and television in France.[5] A two-part TV film, Companeez’ A la recherche only touches on the events of the novel’s first volume in passing, and mostly via flashback: a decision based, perhaps, on the availability of the Schlöndorff film and a fortiori the fact that, in France at least, the “essentials” of Du côté de chez Swann might reasonably be considered to be well-known to the target audience.

The film opens amidst the bright sunshine and sea-spray of Balbec, Proust’s imaginary Normandy resort town (based on Cabourg, where these scenes are filmed). The first instalment of the film begins, thus, with A l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs, moves on to the Parisian societal scenes of Le Côté de Guermantes and closes with the early part of Sodome et Gomorrhe and the staging of one of the protagonist’s most important discoveries about the multifaceted nature of human sexuality – the courtship (and lusty physical encounter) of the baron de Charlus and the tailor Jupien. The second instalment of the film moves, as per the novel, from Sodome et Gomorrhe to the fraught and airless confines of the Albertine cycle (the volumes mentioned above, La Prisonnière and Albertine disparue, unforeseen in Proust’s pre-war vision of his novel) and on to Le Temps retrouvé. This latter, despite being granted only twenty-five minutes of the film’s four-hour total running time, is forcefully conveyed as the culmination (and, in circular fashion, the starting point) of the protagonist’s vocation.

Given the vast time-investment that a reading of Proust’s novel represents, we might be justified in raising an eyebrow about the merits of an adaptation that aspires to squeeze the Recherche into just four hours. Can Proust really be “done” in the time it takes an enthusiastic amateur to run the New York City Marathon? Naturally Companeez has to trim, compress and condense, but overall her achievement is impressive. Those of us critical of the omission of this or that cherished element would do well to recall that on even our most careful readings of the novel we miss nuances or fail to retain details. As Roland Barthes in a moment of cheery frankness has it, the good thing about Proust is that from one reading to the next you never skip the same passages.[6] Companeez moves us along apace but not so fast that we feel rushed. The exception perhaps comes when the the “séjour à Venise” tracks in thirty seconds the deserted city, Carpaccio’s Healing of a Possessed Man and a by-now familiar image of the protagonist framed by an open window. This last shot recalls his attitude upon first beholding the sea from the Grand Hôtel at Balbec, an experience that reappears in the involuntary memory sequence of Le Temps retrouvé).

Companeez’ adaptation, for all its relative brevity, does bring Proust’s kaleidoscopic vision of French society around the dawning of the twentieth century to the screen with vigour and panache. Here is the fascinating mixing of classes in the less formal bains de mer environment; the relentless climb of Mme Verdurin from wealthy bourgeoise to titled grande dame; the dazzling spectacle of high society, flounces, frills, top hats and monocles to the fore; and the impact of war on various facets of life in the French capital.[7] Beautifully costumed and thoughtfully shot (albeit with an over-reliance on mirrors and windows as framing devices reflecting the multi-layered human subject that is at the heart of Proust’s modernity), this is an adaptation whose attention to detail repeatedly rewards the keen-eyed viewer. Portraits we can make out on the walls of the protagonist’s bedroom are those of Proust’s own parents; photographs we glimpse on his sideboard show Anatole France, a guiding figure for the youthful Proust, and Théophile Gautier, whose novel Le Capitaine Fracasse he adored in his formative years. Similarly hawthorn blossoms decorating the bedspread in Paris melt into a flashback of the “aubépines” of the narrator’s childhood in Combray. Albertine, dressed in a gown of gold, sequins and intricate adornment, in the scene from La Prisonnière known as “la regarder dormir,” bears a striking, troubling and uncanny embodiment of Klimt’s The Kiss, painted in 1908-09, precisely when Proust began drafting his novel. In Companeez’ closing set-piece, the fragile, aged Duc de Guermantes, with halting speech and Parkinsonian tremor, sways uncertainly atop padded crutches, a nod to Proust’s image in the novel’s final sentence, of experiences through time leaving the elderly staggering as if “juchés sur de vivantes échasses” (RTP, IV, 625).

Companeez’ film, then, offers a wealth of visual riches, and also uses music of the period and music cherished by Proust to great effect, tying together disparate moments much as recurring metaphors and motifs do in Proust’s text. This said, in the film there is a certain flatness to the adaptation of rapturous aesthetic revelation from the novel – when the protagonist visits the painter Elstir’s studio in Balbec for the first time, or when he hears the mesmerizing music that he will discover in La Prisonnière to be Vinteuil’s (hitherto unknown) septet. These are moments of astonishing literary virtuosity, linguistic high-wire acts that conjure colour, perspective, melody, memory, elation, surprise, as well as inarticulate, gut-felt pleasure. Much of their magic occurs in the intimate arena of the reader’s mind as she follows the sinuous path of Proust’s extraordinary prose. Such inward intensity is somehow dissipated when rendered concrete on canvases in a ‘real’ studio, or played by ‘real’ musicians in a salon: even accompanied by the narrator’s impassioned, often breathless voiceover.

Students of French history and culture will find much of interest in Companeez’ rendering of Proust’s Paris: the social dynamics, the off-hand anti-Semitism, the attitudes to sexuality that mark out a world in transition. While letters and letter-writing are prominent in the depiction of characters’ inter-relations, towards the end of the film Mme Verdurin very pointedly uses a telephone during a wartime soirée. Here is a world as Proust experienced it, between the quaintness of the starched aprons of domestic servants on the one hand, and the technological advances of modern times on the other.[8]

Volker Schlöndorff’s adaptation of the Recherche’s famous flashback to the narrator’s parents’ friend Charles Swann’s tortured love story, sets the film resolutely in nineteenth-century Paris, where much of the day is spent dressing, undressing and re-outfitting oneself for the next social engagement. Footmen stand at every door, banknotes are large like sheets of writing paper and the conveyance of choice is the carriage and pair. Schlöndorff’s interiors are oppressively crowded with heavy furniture through which Jeremy Irons’s Swann weaves, now wetting his moustachioed lips in anticipation, now staggering under the weight of revelations of possible infidelities. As a period piece of cinéma du patrimoine, Swann in Love successfully conveys the rigidities of social convention against which its protagonist revolts in taking up with the demi-mondaine Odette de Crécy. Neither Schlöndorff nor Companeez makes much space for the Dreyfus Affair. They do, however, like Proust, both make ample use of flashback and show central characters turning from vigorous to aged and physically diminished adults. Companeez is particularly stark in her portrayal of the human form, as much in the violence of the narrator’s grandmother’s mental and physical demise as in the abundant nakedness of the jeunes filles in the fantasies the protagonist weaves around Albertine’s possible lesbian proclivities. Extreme close-ups of faces, of eyes and lips, and of reflections of characters in intimate, unguarded moments punctuate Companeez’ film, communicating the relentless scrutiny of Proust’s narrator, probing beyond superficial acquaintance to the depths of understanding. This adapted Recherche goes a long way towards capturing the preoccupations and peculiarities of Proust’s vast novel. It will raise questions, pique curiosities and – one hopes – prompt some of its viewers, at least, to (re-)turn to Proust’s novel with a thirst for more.

Nina Companeez, Director, À la recherche du temps perdu, 2011, Color, 230 min, France, Ciné Mag Bodard, France Télévision, Arte France, TV5 Monde, Radio Télévision Suisse

NOTES

- “Film and Fiction: Hitchcock’s Vertigo and Proust’s ‘Vertigo,’” MLN 102:4 (1987), 1171-81. See also Hervé Picherit, “Une madeleine peut en cacher une autre: un dialogue mythique sur le Temps entre Marcel Proust, Alfred Hitchcock et Chris Marker,” French Studies 2 (2012), 193-207.

- Marcel Proust, A la recherche du temps perdu, ed. by J.-Y. Tadié, 4 vols (Paris: Gallimard, 1987-89), I, 157; further references will take the form RTP, followed by volume number/page number.

- Those interested in the broad question of Proust and screen adaptation are very well served by Martine Beugnet and Marion Schmid’s co-authored volume Proust at the Movies (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004) and the edited collection Proust et les images: peinture, photographie, cinéma, vidéo, ed. by Jean Cléder and Jean-Pierre Montier (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2003).

- For a concise and stimulating survey of Proust adaptation, see Vincent Ferré’s essay “Proust à l’écran”: http://www.magazine-litteraire.com/actualite/breve/proust-ecran-31-01-2011-33292 [accessed 11 February 2016].

- A la recherche du temps perdu, adapté et realisé par Nina Companeez, Koba Films, 2011 [DVD, 2 discs].

- Roland Barthes, Le Plaisir du texte (Paris: Seuil, 1973), p. 22.

- For sensitive and insightful readings of the social and the socio-political in Proust, see Edward J. Hughes, Proust, Class, and Nation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011) and Jacques Dubois, Pour Albertine: Proust et le sens du social (Paris: Seuil, 1997). See additionally the chapters by Hughes, “Politics and Class’ and ‘The Dreyfus Affair’,” and the chapter by Brigitte Mahuzier, “The First World War,” in our Marcel Proust in Context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), pp. 160-66; 167-73; 174-80. For detailed analysis of Proust and the Great War, see Mahuzier, Proust et la guerre (Paris: Champion, 2014) and Philippe Chardin and Nathalie Mauriac Dyer, eds, Proust écrivain de la Première Guerre mondiale (Dijon: Editions universitaires de Dijon, 2014).

- On this point, see Antoine Compagnon’s landmark study, Proust entre deux siècles (Paris: Seuil, 1989).