Issue 3

Madison Smartt Bell’s trilogy set during the Haitian Revolution has been praised more for its vivid array of fictional characters than its treatment of historical events. Historians have reason to doubt whether the slave revolt of 1791 was started by white men, or yellow fever deliberately used to preserve black independence in 1803. But the special truth of fiction really depends on creating a sense of authenticity, of capturing time, place, and personality. In Bell’s novels the people are all real, even the historical ones. For once the complexity of character matches the complexity of events. The profound enigma that was Toussaint Louverture makes him the perfect axle around which everyone else’s often brutal stories turn.

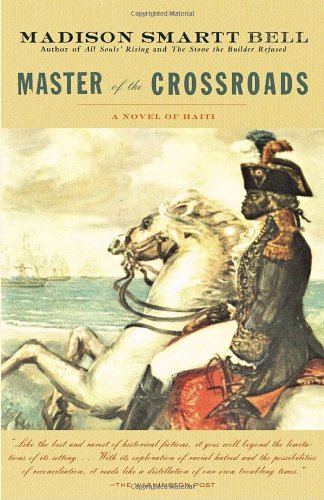

Madison Smartt Bell’s Haitian Revolution Trilogy

Jeremy D. Popkin

University of Kentucky

Madison Smartt Bell’s All Souls’ Rising, a historical novel set in the Haitian Revolution that began with the slave uprising of 1791, changed at least one reader’s life. As a result of reading it, I moved into an entirely new field of research, on an aspect of French history that I had previously known almost nothing about. I continue to be impressed by his achievement. All Souls’ Rising and the two subsequent volumes of his trilogy cover the drama of the Haitian Revolution from the beginning of the slave uprising in 1791 to the final defeat of Napoleon’s army and the declaration of Haitian independence in 1804. Bell’s books have undoubtedly brought the story of the Haitian Revolution to more readers than any of the many works academic historians have published on the subject in the past twenty years.

I initially read Bell’s book almost as a work of pure fiction: I was captured by the story even though I had no sense of whether it bore any relationship to historical reality. That I even read beyond the first page surprises me a bit now. All Souls’ Rising begins with a scene of nightmarish violence: the protagonist, Doctor Hébert, finds himself confronting a slave woman nailed to an upright log, left to die by her master as punishment for having killed her own baby. I don’t usually have much stomach for such graphic horror, but somehow I went on reading. Perhaps I realized, as I read Bell’s description of the matter-of-fact manner in which Bell’s Doctor Hébert, after contemplating the dying slave woman, goes on to dine with the white plantation-owner who had murdered her, that Bell had found a powerful way of conveying, in just a few lines, and without any intrusive moralizing, the glaring contradiction between the civilization of the French Enlightenment and the brutality of slavery. Doctor Hébert, the main character in the more than 2000 pages of Bell’s trilogy—All Souls’ Rising, Master of the Crossroads, and The Stone that the Builder Refused—is jolted by the colonists’ cruelty, but he does not take it upon himself to oppose it. Bell trusts his readers enough to let them judge the actions of his characters for themselves, rather than trying to dictate their reactions. In that respect, his fiction has something in common with good historical writing.

I initially read Bell’s book almost as a work of pure fiction: I was captured by the story even though I had no sense of whether it bore any relationship to historical reality. That I even read beyond the first page surprises me a bit now. All Souls’ Rising begins with a scene of nightmarish violence: the protagonist, Doctor Hébert, finds himself confronting a slave woman nailed to an upright log, left to die by her master as punishment for having killed her own baby. I don’t usually have much stomach for such graphic horror, but somehow I went on reading. Perhaps I realized, as I read Bell’s description of the matter-of-fact manner in which Bell’s Doctor Hébert, after contemplating the dying slave woman, goes on to dine with the white plantation-owner who had murdered her, that Bell had found a powerful way of conveying, in just a few lines, and without any intrusive moralizing, the glaring contradiction between the civilization of the French Enlightenment and the brutality of slavery. Doctor Hébert, the main character in the more than 2000 pages of Bell’s trilogy—All Souls’ Rising, Master of the Crossroads, and The Stone that the Builder Refused—is jolted by the colonists’ cruelty, but he does not take it upon himself to oppose it. Bell trusts his readers enough to let them judge the actions of his characters for themselves, rather than trying to dictate their reactions. In that respect, his fiction has something in common with good historical writing.

Once I had read All Souls’ Rising, I could not stop myself from asking a historian’s question: I wanted to know how much of it was historically accurate. At the time, the great boom in research on the Haitian Revolution to which I have now made my own contribution was just beginning. I read C. L. R. James’ Black Jacobins and Carolyn Fick’s The Making of Haiti: The Saint-Domingue Revolution from Below, and I discovered that Bell had done a serious job of research.[1] I was still somewhat mystified as to how he had managed to create such convincing characters and construct such a vivid picture of the colony during this great upheaval. Part of the answer came to me when I put his book on the reading list for an NEH summer seminar I directed at the Newberry Library in 2001. Poking around in the library’s outstanding Caribbean-history collection, I found the published memoirs of the French plantation-owner Gros and the doctor and naturalist Michel-Etienne Descourtilz and realized that many of the adventures of Bell’s fictional Doctor Hébert were based on episodes in their accounts.[2] I also realized how creatively Bell had used these materials. He had, in effect, fused Gros and Descourtilz to create a single character whose experiences would span the whole of the revolutionary period, whereas Gros’s memoir covered only the initial events of the uprising in 1791 and Descourtilz did not arrive in Saint-Domingue until 1799. In addition, Bell had infused Doctor Hébert with a mildly critical attitude toward the slave system and, above all, with a willingness to rethink his initial attitudes in the light of his experiences, which his historical forebearers, Gros and Descourtilz, did not exhibit. In Bell’s trilogy, the public drama of the Haitian Revolution is paralleled by the interior psychological drama of his main character’s transformation.

The theme of the seminar I taught in 2001 was the making of new identities during the French Revolution, and I assigned Bell’s novel because I had been particularly impressed by the way in which he imagined not only Doctor Hébert’s transformation but also that of the second central figure in his book, the black slave Riau who joins the insurrection and whose destiny comes to be intertwined with that of Doctor Hébert. Through the character of Riau, Bell was able to bring to life the power of vodou, the religion of the slaves, and the way in which he created a distinctive voice for Riau impressed me deeply. In creating such a character, Bell was, of course, taking advantage of the freedom that novelists can claim to venture where historians do not dare to tread. In the absence of any testimonies from the black slaves who participated in the Haitian uprising, we are limited to cautious speculation based on records from the whites. Bell drew on anthropological studies of vodou and other sources, but Riau is truly his own invention. Whether Bell’s imagined character really resembles the actual blacks who participated in the uprising is, of course, essentially unknowable. Riau, with his contradictions and his capacity for growth, seems more plausible than the stereotypical black freedom fighters imagined by some historians, and even of Toussaint Louverture, as Bell portrays him in his novels.[3] At the end of Bell’s trilogy, after not only Toussaint Louverture but the majority of the book’s characters have met their tragic ends, it is Riau who has the last word. The former slave thinks back on the moments when he and Doctor Hébert sat together drinking rum, recalling how their experiences had made friends of two men who came from entirely separate worlds.

The theme of the seminar I taught in 2001 was the making of new identities during the French Revolution, and I assigned Bell’s novel because I had been particularly impressed by the way in which he imagined not only Doctor Hébert’s transformation but also that of the second central figure in his book, the black slave Riau who joins the insurrection and whose destiny comes to be intertwined with that of Doctor Hébert. Through the character of Riau, Bell was able to bring to life the power of vodou, the religion of the slaves, and the way in which he created a distinctive voice for Riau impressed me deeply. In creating such a character, Bell was, of course, taking advantage of the freedom that novelists can claim to venture where historians do not dare to tread. In the absence of any testimonies from the black slaves who participated in the Haitian uprising, we are limited to cautious speculation based on records from the whites. Bell drew on anthropological studies of vodou and other sources, but Riau is truly his own invention. Whether Bell’s imagined character really resembles the actual blacks who participated in the uprising is, of course, essentially unknowable. Riau, with his contradictions and his capacity for growth, seems more plausible than the stereotypical black freedom fighters imagined by some historians, and even of Toussaint Louverture, as Bell portrays him in his novels.[3] At the end of Bell’s trilogy, after not only Toussaint Louverture but the majority of the book’s characters have met their tragic ends, it is Riau who has the last word. The former slave thinks back on the moments when he and Doctor Hébert sat together drinking rum, recalling how their experiences had made friends of two men who came from entirely separate worlds.

Having lived, through their letters and documents,with many of the participants in the Haitian Revolution myself for some years now,[4] I find some of Bell’s characters less plausible than I did on first reading. Although he deserves credit for recognizing the distinctive role of people of mixed race in Saint-Domingue’s revolutionary history and for creating important characters drawn from this group, his depictions of Nanon, the mulatto courtesan with a heart of gold who becomes Doctor Hébert’s lover, and of her brother Choufleur, to take two examples, strike me as less successfully realized than those of some of his other creations. The last volume in the trilogy is not as compelling as the first two. There are too many battle scenes, too many more or less indistinguishable characters, and, in my opinion, an overly adulatory portrayal of Toussaint Louverture, elevated to the status of a martyred saint. However, I am still awed by Bell’s achievement. He dared to conceive a project on a scale that no professional historian could imagine; his 2000-page trilogy is six times longer than Laurent Dubois’s widely acclaimed Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution.[5] Unlike most historians, Bell has taken it upon himself to imagine both the interior and the public lives of the people of the past, and he has managed to reconstruct both of these dimensions of their existence in convincing ways.

Having lived, through their letters and documents,with many of the participants in the Haitian Revolution myself for some years now,[4] I find some of Bell’s characters less plausible than I did on first reading. Although he deserves credit for recognizing the distinctive role of people of mixed race in Saint-Domingue’s revolutionary history and for creating important characters drawn from this group, his depictions of Nanon, the mulatto courtesan with a heart of gold who becomes Doctor Hébert’s lover, and of her brother Choufleur, to take two examples, strike me as less successfully realized than those of some of his other creations. The last volume in the trilogy is not as compelling as the first two. There are too many battle scenes, too many more or less indistinguishable characters, and, in my opinion, an overly adulatory portrayal of Toussaint Louverture, elevated to the status of a martyred saint. However, I am still awed by Bell’s achievement. He dared to conceive a project on a scale that no professional historian could imagine; his 2000-page trilogy is six times longer than Laurent Dubois’s widely acclaimed Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution.[5] Unlike most historians, Bell has taken it upon himself to imagine both the interior and the public lives of the people of the past, and he has managed to reconstruct both of these dimensions of their existence in convincing ways.

Bell’s books do not lend themselves easily to classroom use. Their richness comes from their length and their profusion of characters and incidents, but those qualities make it difficult to assign them to students. The raw violence of the opening scene of All Souls’ Rising and several other episodes could also be difficult for many students to digest. For historians, however, Bell’s works are well worth reading. His novels challenge us to expand the boundaries of our own thinking about the past, to use our imaginations more creatively even as we insist on our duty to remain true to what we find in our documents and, above all, to recognize that this history was made by human beings, with all their contradictions and weaknesses, and that it speaks to us precisely because of this human dimension.

- C. L. R. James, The Black Jacobins : Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution (New York: Vintage, 1989, orig. published 1938); Carolyn Fick, The Making of Haiti: The Saint-Domingue Revolution from Below (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 1991).

- [Gabriel] Gros, An Historick Recital, of the Different Occurrences in the Camps of Grande-Reviere Dondon, Sainte-Suzanne, and others, from the 26th of October, 1791, to the 24th of December, of the same year (Baltimore, Md.: Samuel and John Adams, 1793); Michel-Etienne Descourtilz, Voyages d’un naturaliste, 3 vols. (Paris: Dufort, 1809).

- Bell later published Toussaint Louverture: A Biography (New York: Pantheon, 2007), which has met a cooler reception than his fictional trilogy.

- My discovery of the Gros and Descourtilz memoirs led me to search for other first-hand accounts of the revolutionary period, some of which I brought together in Facing Racial Revolution: The Haitian Revolution and the Abolition of Slavery (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), and the dramatic documents I found about the events of June 20, 1793, when the colonial capital of Cap Français was burned to the ground and the first French proclamation offering freedom to the slaves was issued, eventually led me to write You Are All Free: The Haitian Revolution and the Abolition of Slavery (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

- Laurent Dubois’s Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2004).

Madison Smartt Bell, All Souls’ Rising, New York: Pantheon, 1995, 544 pp.; Master of the Crossroads, New York: Pantheon, 2000, 752 pp.; The Stone that the Builder Refused, New York: Pantheon, 2004, 768 pp.