Robin Walz

University of Alaska Southeast

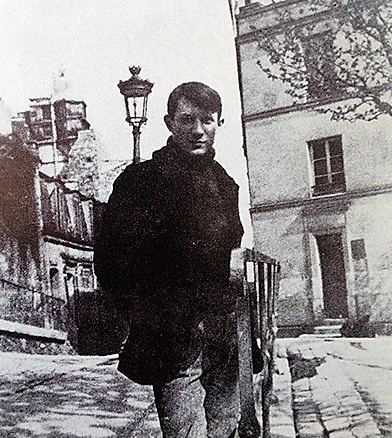

Pablo Picasso arrived in Paris in 1900 to launch his artistic career. Four years later, he met the artist’s model Fernande Olivier, who became his muse and lover for the next eight years as Picasso worked toward establishing his modernist idiom. Scenarist Julie Birmant and illustrator Clément Oubrerie have teamed up to produce Pablo, a graphic biography that imagines the lives of Picasso and Olivier within the artistic and social milieu of Montmartre in that opening decade of the twentieth century. Readers steeped in the Bohemian myth of the Bateau-Lavoir and anecdotes about Picasso’s early years in Paris will find the terrain familiar. Fernande Olivier’s story is less well known and, in my view, is the more illuminating one.

Julie Birmant is a Belgian documentary filmmaker and a cultural reporter for France Culture. Her first foray into bandes dessinées, or graphic novels, was Drôles de femmes, a collection of humorous and saucy biographical vignettes about contemporary Belgian and French actresses, authors, and cartoonists. Currently, she has embarked on a new comics adventure series loosely inspired by the life of American dancer Isadora Duncan. [1] Clément Oubrerie is a French illustrator who produced children’s books for the first decade of his career before moving into comics in 2005, most notably the award-winning Aya de Yopougon series written by Marguerite Abouet (Gallimard, 6 vols., 2005-2010). [2] Birmant and Oubrerie’s Pablo was originally published by the major French comics firm Dargaud in four parts: Max Jacob (2012), Apollinaire (2012), Matisse (2013), and Picasso (2014). The independent London-based publisher SelfMadeHero has translated Pablo into English and combined the issues into a single volume as part of its growing “Art Masters” series of graphic-novel biographies of modern artists, which includes volumes on Vincent Van Gogh, Edvard Munch, Salvador Dalí, Paul Gaugin, and René Magritte. [3] Unlike many of the titles in the “Art Masters” series, whose illustration techniques play upon the works and aesthetic techniques of the various artists in a creative reimagining of their lives, Pablo is a straightforward biography about Picasso and Olivier, chronologically told and visually rendered through realist comics.

The biographical narrative of Pablo is guided by caption voiceovers delivered by Fernande Olivier as an old woman, reflecting upon the time, decades ago, when her life intersected with Picasso’s. For source material, Birmant has drawn heavily upon Olivier’s Picasso et ses amis (1933) and Souvenirs intimes (1956, published 1988), translated into English as Loving Picasso. [4] The effect of Birmant relying upon Olivier’s latter-day recollections becomes, in the graphic biography, a string of episodes in their lives, apart and together, with time marching on. In some ways this makes sense, as these years cover Picasso’s early artistic career, before he gained international recognition as a modernist genius, and by then Olivier was completely out of his life. But in Pablo this produces uneven stories about divergent lives, lacking cohesion as a graphic biography. Whose story is this? The answer is somewhat confused, and it may help to separate out their parallel and sometimes overlapping life stories.

The story of Picasso’s life covered by Birmant and Oubrerie is well traveled, and Pablo celebrates the young artist’s apocryphal escapades. A precocious youth recognized as an artistic prodigy in Barcelona, Picasso arrived in Paris during the Exposition universelle of 1900 to celebrate his nineteenth birthday with fellow Barcelonan and aspiring artist Carlos Casagemas. The two were taken under the wings of Catalan artists Isidre Nonell and Ramon Casas, who had relocated to Paris, and by Montmartre painter Miguel Utrillo. During their first year, shuttling back and forth between Paris and Barcelona, they struggled enormously. Carsagemas committed suicide over a soured love affair, and Picasso’s life was fraught with anxiety dreams about artistic failure, opportunistic art dealers who nickel and dimed him, and short-term affairs. Picasso’s first admirers and enthusiasts were poets Max Jacob and Guillaume Apollinaire, who had financial and artistic problems of their own. They became fast friends, and the trio would prowl the streets of Montmartre at night, carousing and firing Alfred Jarry’s revolver into the air. Picasso moved into a dilapidated factory building in Montmartre, dubbed the Bateau-Lavoir (“laundry boat”) by Jacob, and over the next decade the studio-residence became a rotating collective of artists and writers.

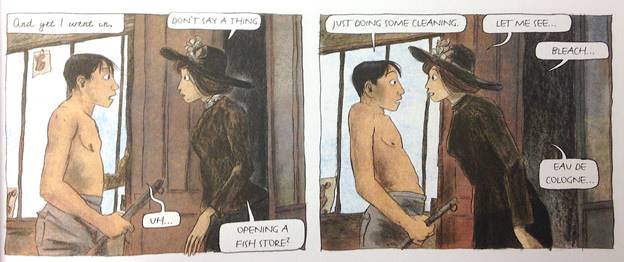

Fernande Olivier had her own troubles during these years, although on an altogether different register from Picasso’s.  Born Amélie Lang in Fontenay-sous-Bois, and sold as a child by her parents to an abusive aunt, she was married at age eighteen to a ne’er-do-well named Paul Percheron who had date-raped and impregnated her. Enduring continued beatings from her husband and suffering a miscarriage, Lang escaped to Paris. Penniless, she was befriended by aspiring sculptor Gaston Lebaume, called “Laurent Debrienne” in Olivier’s journal and in Pablo, and she soon becomes his model and mistress. Renaming herself Fernande de la Baume, and then Olivier, she earned an independent income working as a model for a number of aspiring artists, but soon tired of the sexual favors expected from her. In Montmartre, Olivier made the acquaintance of Max Jacob, who called her “la belle Fernande” and introduced her to Picasso at the Bateau-Lavoir. From 1904 to 1907, Fernande became Pablo’s lover, model, and domestic companion (a span of time that roughly corresponds to what art historians label Picasso’s blue, pink, and primitivist periods). Theirs was an unsettled relationship. Picasso was possessive, jealous, self-absorbed, and neglectful of his personal hygiene. Despite Picasso wanting her to be a kept woman in their studio-apartment, Olivier insisted on independence in her professional and private relationships, as well as in her sexual encounters.

Born Amélie Lang in Fontenay-sous-Bois, and sold as a child by her parents to an abusive aunt, she was married at age eighteen to a ne’er-do-well named Paul Percheron who had date-raped and impregnated her. Enduring continued beatings from her husband and suffering a miscarriage, Lang escaped to Paris. Penniless, she was befriended by aspiring sculptor Gaston Lebaume, called “Laurent Debrienne” in Olivier’s journal and in Pablo, and she soon becomes his model and mistress. Renaming herself Fernande de la Baume, and then Olivier, she earned an independent income working as a model for a number of aspiring artists, but soon tired of the sexual favors expected from her. In Montmartre, Olivier made the acquaintance of Max Jacob, who called her “la belle Fernande” and introduced her to Picasso at the Bateau-Lavoir. From 1904 to 1907, Fernande became Pablo’s lover, model, and domestic companion (a span of time that roughly corresponds to what art historians label Picasso’s blue, pink, and primitivist periods). Theirs was an unsettled relationship. Picasso was possessive, jealous, self-absorbed, and neglectful of his personal hygiene. Despite Picasso wanting her to be a kept woman in their studio-apartment, Olivier insisted on independence in her professional and private relationships, as well as in her sexual encounters.

Picasso and Olivier’s on-again, off-again relationship constitutes a larger portion of Birmant and Oubrier’s book. Shortly after they moved in together, Gertrude and Leo Stein became Picasso’s first bourgeois patrons, a stroke of good fortune that exposed him to the work of Cézanne, Renoir, Gauguin, Degas, and Lautrec collected by the Steins, and to influential art dealers such as Ambroise Vollard. Over time, however, Olivier grew resentful of the ways in which Gertrude Stein imposed herself on their lives, particularly the ninety sitting sessions for Picasso’s portrait of her during which Fernande was expected to play hostess. For a change of scenery, the two embarked upon an extended stay in Barcelona, a largely exhilarating experience for Picasso and a mixed bag for Olivier, who didn’t speak Catalan and was unfamiliar with local customs. During the sojourn, Picasso became interested in primitivism and exoticism, while Olivier felt increasingly alienated and, after reading Gauguin’s Noa Noa, saw parallel obsessions in her artist lover.

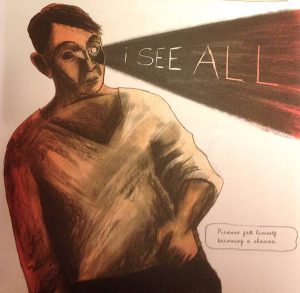

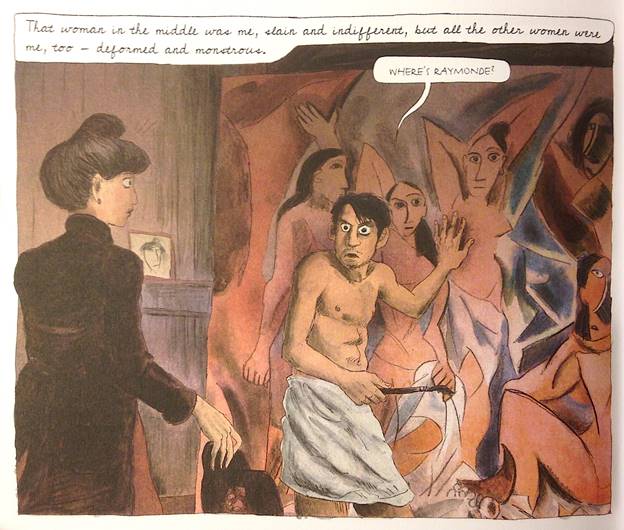

Picasso and Olivier’s relationship was further strained after returning to Montmartre. Picasso met Henri Matisse at one of Gertrude Stein’s dinner parties, and subsequently the two become jealous rivals, artistically and for Olivier’s affections. Picasso also received new artistic inspiration from indigenous African masks and statuettes (provided by Apollinaire’s theft from the Louvre’s collection), which Birmant and Oubrerie mark as a turning point for Picasso as the burgeoning “shaman” of modern art. While Picasso was fixated on achieving artistic greatness, Olivier responded by attempting to rekindle their relationship by starting a family. She became pregnant with Picasso’s child, but had a miscarriage. She later adopted a girl named Raymonde from a Catholic orphanage, but was worn down by the drudgery of domestic life and returned the child after she discovered Picasso sketching nudes of her. Angered by Olivier’s actions, Picasso threw himself even further into his art and their estrangement became permanent.

Although they were no longer living together, Picasso continued to use Olivier as a model for his paintings and sculptures during this primitive-cubist period, most notably in his “Bordello,” later titled Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. While his artist friends, patrons, and critics ridiculed the painting (with the notable exception of Apollinaire), this signaled the advent of Picasso the Modernist. In the final pages of the book, Picasso is pursuing his modernist trajectory, influenced by the post-impressionist painter André Derain and cubist Georges Braque, and he fêtes the naïve painter the Douanier Rousseau in a now famous banquet held at the Bateau-Lavoir. For her part, Olivier makes a circuit of their artist friends and patrons, establishing relationships with them independently of Picasso. The graphic biography closes with a final conversation between Olivier and Max Jacob and a full-page portrait of “Belle Fernande” in her final years.

What is gained by imagining the lives of Pablo Picasso and Fernande Olivier through comics, rather than letters, diaries, or a standard biography? The answer emerges from the ways in which comics communicate through visual narrative strategies. In the case of Pablo, Birmant and Oubrerie present a chronological biographical account through realistically drawn comics. While short of photo-realism, the imagery in Oubrerie’s panels adheres to the aesthetics of natural portraiture, three-dimensional perspective, and visual details that mark individuals and settings as unique and distinct from one another. [5] He evokes the lived landscape of Paris and Montmartre in the early twentieth century that Picasso and Olivier inhabited and where they negotiated their relationship. Such visual storytelling is especially important for readers today, who have no lived memory of the cultural geography described in contemporaneous literary and documentary sources. They must rely on the supplemental visual imagery of post-impressionist paintings, Eugène Atget’s photographs, or silent films to provide the referents. The full-color realist mode of Pablo may provide a better medium to pull readers into this bygone era, through the combination of written dialog and visuals, narrated in transitions from panel to panel.

Oubrerie’s illustrations are effective as his realistic imagery conforms to the fluctuations of everyday life and settings. Overcast or rainy days in Paris, for example, are muted in blue-gray, whereas sun-parched Spain basks in landscapes with a ruddy yellow hue. Interior scenes that rely upon natural light through windows take on a flat green or neutral brown tinge, while interiors without windows are dark and somewhat obscured. Oubrerie is attentive to artificial lighting as well. The electric lights at the Exposition universelle adorn buildings and streets with auras. The abundant lamps in art salons and in bourgeois dining rooms warm the brown environs with a warm, yellowish glow. The single lamps in Bohemian studios at night deliver a few circles of dim light, fading into darkness. This careful use of lighting throughout the book provides readers with a specific awareness of social and cultural spaces, as they were experienced a century ago.

The place where the realist storytelling is used most effectively is in Fernande Olivier’s life story. This is due in all likelihood to Birmant’s reliance upon Olivier’s journals and letters as source material; the voice the reader “hears” is hers. Her story is also more emphasized than Picasso’s through the matching of Olivier’s “voiceover” captions and word balloons, which reinforce each other and provide her character with a strong first-person identity. By contrast, Picasso’s word balloons are juxtaposed to Olivier’s commentary, which remove him to the third person and draw attention to the tensions between the two. Word balloons are also used to inform the English reader about the original language spoken, with white balloons indicating French and lavender ones Catalan. This creates a sense of realist narrative, as Picasso and his friends speak to each other nearly exclusively in Catalan when they first arrive in Paris. It also reinforces Olivier’s comments about Picasso’s French at the time being nearly unintelligible. When Pablo and Fernande travel to Barcelona, the conversations in lavender word balloons are readily understood by the English reader, but are opaque to the exclusively French-speaking Olivier, who is sometimes confused by what is happening and has to rely upon gestures and visual clues to grasp the situation. In these ways, comics narrative techniques amplify the dual biography, Olivier’s more so than Picasso’s.

Perhaps the most challenging aspect of Pablo is its sheer size, nearly 350 pages. This makes it nearly twice as long as the other titles in the SelfMadeHero’s “Art Masters” series, which often include supplemental sketches, illustrations, essays, source materials and references. No doubt, combining the four volumes of the Dargaud Pablo series into a single volume made the inclusion of such additional materials difficult. The other volumes in the series also feature the artists’ paintings through a variety of cartooning techniques, whereas Oubrerie’s realistic imagery does not imitate Picasso’s styles and few of his artworks are reproduced. Oubrerie frequently depicts Picasso sketching, painting at the easel, or fashioning a sculpture, and the walls of his studio are abundantly filled with studies and works in progress. But representations of Picasso’s works are largely missing in Pablo, aside from his portraits of Benedetta Canals (1905) and Gertrude Stein (1905-1906), each rendered as the mirror image of the renowned painting. The only work to receive substantial attention is Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). On a few occasions, however, Oubrerie breaks out of the realist mode to allow purely imaginary scenes to propel the story. One of the traumatic events in Picasso’s childhood was the death of his younger sister Conchita, and Oubrerie skillfully works fantastic imagery into his nightmares. There is also a full-page reworking of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon where the cubist figures have the heads of Picasso’s artistic rivals and disappointed supporters, who proclaim the painting a failure. However, Oubrerie rarely makes such departures from the realist idiom.

Beyond readers of the “Art Masters” series or graphic novel aficionados, the intended audience for this graphic biography is not altogether clear. For those unfamiliar with Picasso’s biographical details, this book provides a rich introduction to his social milieu, sexual liaisons, and artistic aspirations. For those already familiar with Picasso’s life story, the treasures may be fewer. In my view, the pleasures of Pablo emerge primarily from learning about and visualizing the details of Fernande Olivier’s life. More than “Picasso’s muse,” Olivier was a flesh and blood woman whose experiences were likely typical for a single woman from an unremarkable background, striving to live independently in Paris during the early twentieth century. In this graphic biography, Olivier’s story about the underprivileged and feisty woman making her way is more compelling than the one about Picasso as the Modernist Hero.

Julie Birmant and Clément Oubrerie. Pablo. Translated by Edward Gauvin. Series “Art Masters.” London: SelfMadeHero, 2015.

NOTES

* Photographs from http://www.montmartre-secret.com/2016/12/fernande-olivier-et-picasso-a-montmartre.html

- Julie Birmant and Catherine Meurisse, Drôles de femmes (Paris: Dargaud, 2010). The Isadora Duncan adventure series to date: Julie Birmant and Clément Oubrerie, Il y a une fois dans l’est (Paris: Dargaud, 2015) and Isadora (Paris: Dargaud, 2017).

- The Aya series by Abouet and Oubrerie has been translated into English and published by the Montreal firm Drawn & Quarterly in two volumes: Aya: Life in Yop City (2008) and Aya: Love in Yop City (2009).

- The “Art Masters” series by Self Made Hero (London) to date: Barbara Stok, Vincent, trans. Laura Watkinson (2015); Julie Birman and Cleement Oubrerie, Pablo, trans. Edward Gauvin (2015); Steffen Kverneland, Munch, trans. Francesca M. Nichols (2016); Edmond Baudoin, Dalí, trans. Edward Gauvin (2016); Fabrizio Dori, Gaugin: The Other World, trans. Edward Gauvin (2017); Vincent Zabus and Thomas Campi, Magritte: This is Not a Biography, trans. Edward Gauvin (2017).

- Ferdinand Olivier, Loving Picasso: The Private Journal of Fernande Olivier, trans. Christine Baker and Michael Raeburn, forward Marilyn McCully, epilogue John Richardson (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2001).

- In Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud argues that figurative representations in comics engage the viewer through a “reality-icon continuum”: detailed or “realistic” cartoons evoke specific persons and setting, while simplified or “abstract” cartooning is more universal and open to reader self-identification. See Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (Northhampton, MA: Kitchen Sink Press, 1993).