Eric Reed

Western Kentucky University

Many of the best stories of the Tour de France are so unbelievable that the most skilled fiction writer would have difficulty concocting them. Rarely does the written word do justice to the hyperbolic melodrama of the race’s climaxes, the superheroic caricatures of its heroes in the public imagination, and the near-orgasmic joy that champions’ triumphs unleash in the hearts of the most ardent cycling fans. Legends of the Tour, a graphic-novel history of the famous race by Dutch author Jan Cleijne, succeeds admirably through the power of its images.

Legends is the work of a loving fan and is designed to celebrate through art the Tour’s greatness, especially the greatness of its champions. Cleijne combines evocative, emotionally laden pen sketches with concise narrative and exposition to create a rich pantheon of heroic caricatures and archetypes. The book opens with panels chronicling the Tour’s invention in 1903 by Henri Desgrange, a Paris newspaperman who hoped that the amazing new race would boost sales of his struggling sports daily, L’Auto. With the economy of comic strip, Cleijne captures French society’s ambivalence toward cycling in the early twentieth century. In one panel, a respectable woman on a Parisian grand boulevard gasps and recoils in fright and disgust as a bicyclist zooms by, while in another panel well-dressed ladies whisper and giggle with delight as the first-ever Tour rolls down a road in the capital’s suburbs.[1]

In early chapters, Cleijne’s illustrations depict the raw enormity of the physical challenges posed by the Tour and the superhuman feats of the riders who conquered them. The sparse narration is a strength, not a weakness, of Cleijne’s storytelling that does justice to the experience of spectators in the race’s early days. Most French people who saw the Tour in person glimpsed only a few moments of it as the peloton passed through their town square. In the era before television, fans read about it in their local newspapers and listened to radio broadcasts and had to imagine how exactly the race took place. So, too, does Cleijne induce his readers to use their imaginations to piece together the drama from his evocative imagery.

In his approach to the Tour’s heroes, Cleijne’s novel resembles Roland Barthes’ essay on the Tour in Mythologies.[2] Legends of the Tour presents the Tour’s meanings as enduring and static, a canon of greatness defined by its ideal-type heroes. To develop the canon’s elements, the middle chapters include elaborate caricatures of the incredible deeds and personalities of the Tour’s most celebrated superstars. Entire sections are devoted to the powerful French national team of the 1930s, to Frenchman Jacques Anquetil, who dominated the Tour in the 1950s and 1960s, and to Belgian champion Eddy Merckx. Panels depict crowds and riders feeding off each other’s unbridled enthusiasm and convey nicely the intimate relationship that developed between French fans and their beloved Tour stars. In the Anquetil chapter, Cleijne’s pen captures the melodrama of the 1964 Tour. Before the race began, a famous fortuneteller predicted correctly that Anquetil would falter on the fourteenth stage. Later in the race, Raymond Poulidor, a crowd favorite and Anquetil’s arch-rival, beat his nemesis in a head-to-head climb. It looked like Anquetil would lose the Tour. But the wily, calculating Frenchman mustered his courage, won the pivotal time trial stage at the end of the race, and captured his fifth yellow jersey.

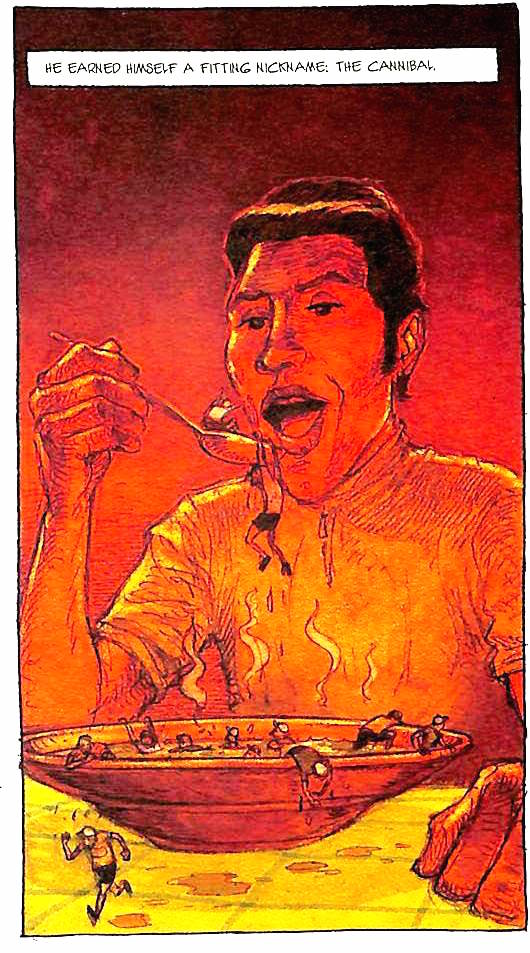

The book is filled with light-hearted, humorous portraits of Tour stars, some of which evoke famous fairy tales and comic-book superheroes. In his Eddy Merckx chapter, Cleijne portrays the Belgian star as a Brobdingnagian cannibal gorging on soup made of fellow riders, in a panel reminiscent of the giant in “Jack and the Beanstalk.” Merckx is considered by many to be the greatest bicycle racer in history and was nicknamed “The Cannibal” in 1969 by the French press for the way he devoured his competitors. In a later chapter, the exciting rivalry between Dutchman Joop Zoetemelk and Bernard Hinault in the late 1970s is shown in Superman-style comic-book art.

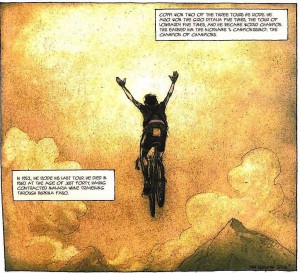

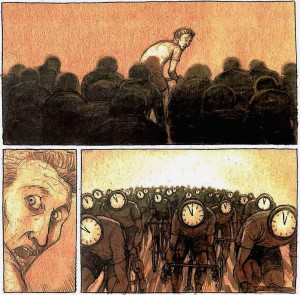

Cleijne inserts heroic “coda” for some of the stars in his book. Italian champion Gino Bartali, called “The Pious” for his deep, overt Catholic faith, rides off into retirement with the setting sun forming a holy halo around his head. Bartali’s rival Fausto Coppi, regarded as perhaps the greatest climber in Tour history, who succumbed tragically to malaria at age forty, soars mid-air over summits with his hands raised in triumph, evoking the last scene of the film Thelma and Louise. Jacques Anquetil, derided by critics as “Mr. Chrono” because he won Tours solely by accumulating individual time trials, pedals frantically and vainly to escape a peloton of stopwatch-headed cyclists. In such images, Cleijne captures well the way that knowledgeable fans continue to memorialize the unique achievements, flaws, and tragedies associated with legendary Tour champions.

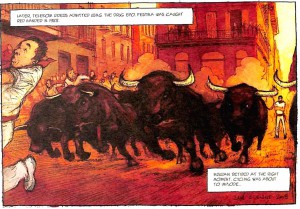

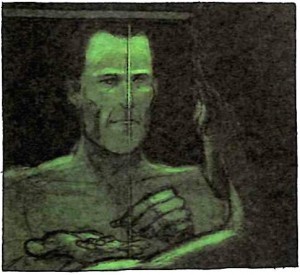

During the period from 1996 to 2010, doping charges tainted nearly every Tour champion and many were stripped of their yellow jerseys. In Legends of the Tour, this pitiful time comes across as an anomaly in the race’s heritage, perpetrated by rotten apples. Cleijne draws some of the defining moments of this scandal-ridden time in hellscape reds, oranges, and browns to convey to the reader evil sullying the Tour’s image. In a set of particularly poignant facing pages, Cleijne portrays the last “good” hero, the quiet, humble Spanish champion Miguel Indurain, in bright yellow opposite a deep brown and red image of bulls stampeding in Pamplona, to signify the unstoppable, destructive doping scandals that gored through the Tour’s good image starting in 1998. That year, police arrested the entire Festina cycling team for EPO use in the middle of the race. Lance Armstrong receives a similar treatment. Cleijne draws the American’s mountaintop victory salute at Sestriere, Italy, in 1999, in dark crimson tones. He uses deep greens and blacks in other frames, explicitly showing Armstrong in dark hotel rooms injecting himself with dope and popping pills. In other green-black panels, Armstrong smirks menacingly as he looks in the mirror, relishing his dark secrets.

Of course, the reality is far grimmer than Cleijne’s drawings. Doping, cheating, and scandal were an integral part of the Tour’s history and public image since its first days. Cheating was so bad in 1904, only the second year of the race – riders caught trains, were pulled up hills by cars, and at one point a violent mob tried to beat up some competitors to help their hometown racer win – that founder Henri Desgrange considered canceling the race for good. Several riders nearly died from amphetamine abuse in the Tours of the 1940s and 1950s, and Jacques Anquetil’s refusal to quit doping tarnished his last years atop the cycling world in the mid-1960s. It is likely, too, that the cycling establishment and the Tour have long been complicit in perpetuating the fiction that cycling’s heroes race clean.[3]

Legends of the Tour also pays tribute to the Tour’s media coverage and to some of the race’s famous newspaper and televised moments. In passages reminiscent of the famous illustrator Pellos, who caricatured the Tour for French newspapers for much of the twentieth century, Cleijne anthropomorphizes mountains and storms that nearly thwarted the yellow jersey hopes of Octave Lapize in 1910 and Jacques Anquetil in 1964. To symbolize Eddy Merckx’s infamous 1975 “meltdown,” when the Belgian champion suffered from a bout of super-exhaustion in the Alps and lost the race for the first time, Cleijne imagines a highly muscled ogre with a sledge-hammer waiting to pound Merckx on the slopes of the mountains.

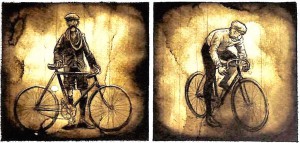

Cleijne illustrated much of the first two chapters, which cover the interwar period, in dark sepia tones to match the color of newspaper photographs of the era. Gradually, as Legends advances to the middle and late twentieth century, Cleijne incorporates richer and brighter colors – especially maillot jaune yellow – into his images to portray the technological, media, and athletic modernization of the Tour. Some of the best drawings are recreations of well-known and oft-republished newspaper photographs, such as Poulidor and Anquetil bumping shoulders during their head-to-head “duel” climb up the Puy-de-Dôme in 1964, and the horrifying image of rising British star Tommy Simpson dying by the Mont Ventoux roadside in 1967 after collapsing due to a drug overdose. The author renders some great televised climaxes, as well, including the unusual “tie” between teammates Greg LeMond and French star Bernard “The Badger” Hinault in 1986, during which the bitter rivals crossed the Alpe d’Huez finish line hand-in-hand, arms raised in triumph. That result cemented the American’s first Tour win, marked the end of Hinault’s dominance, and heralded a period in which non-Frenchmen and non-Europeans came to dominate France’s “national bicycle race.”[4]

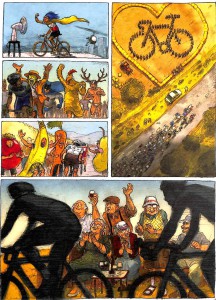

Cleijne celebrates the Tour’s faithful fans throughout the book and draws especially loving portraits in a string of panels at the end of the novel. There, the author portrays a series of famous, costumed superfans who appear every year at the Tour: Didi Senft, a German enthusiast who follows bicycle races for six months a year dressed as a devil and wielding a pitchfork; a Dutch man clad only in a Borat-style green thong bikini; four men wearing banana, carrot, pear and tomato outfits; an enormous chicken, a man with gigantic reindeer horns, Batman, and the title character from Jim Carrey’s The Mask. The fan portraits in this section conclude with a touching rendering of elderly French men and women clapping, waving, cheering, and drinking wine at a small picnic table as the peloton zooms by. Clearly, the author believes that fans’ enduring fervor will resuscitate the Tour’s fortunes as the Armstrong-era doping scandals recede into the past.

By design, Cleijne’s graphic novel is a creative interpretation and is episodic in its treatment of the race’s history and heroes. Legends of the Tour has perhaps two thousand words of text. A reader who knows little about the Tour will not learn much about the complex story of the event or the broader national and international history that its evolution reflected. The more profound meanings and contexts of many of the stories captured in Cleijne’s art simply cannot be conveyed to the casual reader in a graphic novel, even one as delightful as Legends. The Tour, as Georges Vigarello has explained, engrained itself into France’s national imagination and rituals very quickly after 1903.[5] Yet the broader meanings, purposes, and conflicts surrounding the Tour changed as France’s socio-cultural milieu evolved amid war, defeat, victory, and rapid cultural and social transformation.[6] It is impossible, reading solely Legends, to understand the deep resonance of Raymond Poulidor to the French in the 1960s and 1970s, the complex symbolism of French cycling victories after the World Wars and during the Depression, or the ways that Tour stardom reflected the evolution of France’s celebrity culture.[7] Nevertheless, students will love Cleijne’s book and remember it, and its stark, rich images would serve as a very useful departure point for deeper analysis if paired with scholarly works that tease out historical context.[8]

Legends of the Tour is a tremendous pleasure to read, even for those who aren’t Tour fans. When it arrived in the mail last fall, my son, a voracious reader of graphic fiction, picked it up and read it cover-to-cover in one sitting, in about an hour, stopping frequently to marvel aloud to me at the wonderful, evocative, compelling images. I followed my son’s example.

Jan Cleijne, Legends of the Tour, trans. Michele Hutchinson and Laura Watkinson. London: Head of Zeus, 2014.

- Hugh Dauncey and Christopher Thompson explore how bicycling was a sounding board for class, gender, and racial tensions in the Belle Époque. Hugh Dauncey, French Cycling: A Social and Cultural History. Liverpool: University of Liverpool Press, 2013, chapters 2 and 4; Christopher Thompson, The Tour de France: A Cultural History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006, chapter 1.

- Roland Barthes, Mythologies. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1957.

- For overviews of doping and the Tour’s history, see Thompson, Tour de France, chapter 6; Patrick Mignon, “The Tour de France and the Doping Issue,” in The Tour de France, 1903-2003: A Century of Sporting Structures, Meanings, and Values, eds. Hugh Dauncey and Geoff Hare. London: Frank Cass, 2003.

- On the Tour’s history in the context of cultural and commercial globalization, see Eric Reed, Selling the Yellow Jersey: The Tour de France in the Global Era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

- Georges Vigarello, “Le Tour de France,” in Les lieux de mémoire, Vol. 3: Les France, ed. Pierre Nora. Paris: Gallimard, 1992.

- Thompson, The Tour de France.

- On Poulidor’s resonance and French celebrity culture, see Michel Winock, Chronique des années soixante. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1987; Philip Dine, “Stardom on Wheels: Raymond Poulidor,” in Stardom in Postwar France, eds. John Gaffney and Diana Holmes. New York: Berghahn Books, 2007.

- To learn more about teaching graphic novels, it would be useful to revisit Robin Waltz’ enlightening primer, published in FFFH in February 2014 at this link.