Alyssa Goldstein Sepinwall

California State-University San Marcos

A recent wave of scholarship has challenged the idea that French Jews and Muslims are natural enemies. In her 2014 study Muslims and Jews in France: History of a Conflict, Maud Mandel vigorously disputed the widespread notion that “Muslims and Jews in France are on an explosive collision course.” Without ignoring the history of conflicts between members of these communities, she maintained that Muslim-Jewish relations in France have been much more varied. Similarly, in The Burdens of Brotherhood: Jews and Muslims from North Africa to France (winner of the 2016 Society for French Historical Studies Pinkney Prize for best book in French history published by a North American scholar), Ethan Katz has nuanced the history of Jewish-Muslim relations in France and highlighted moments of cooperation. Several Jewish scholars in France, together with Muslim colleagues, have engaged in similar work.[1]

Even before this burst of scholarship in the 2010s, an analogous movement was underway in film. The last fifteen years have witnessed a wave of films, made by French-Jewish directors, which emphasize commonalities and friendships between Jews and Muslims. These include Karin Albou’s La Petite Jérusalem (Little Jerusalem, 2005) and Le chant des mariées (Wedding Song, 2008); Valérie Zenatti’s Une bouteille à la mer (Bottle in the Gaza Sea, 2011); and Lorraine Lévy’s Le fils de l’autre (The Other Son, 2012).[2]

While non-Jewish directors have made important Francophone films on Muslim-Jewish relationships (like Monsieur Ibrahim [2003], Names of Love [2010], and Free Men [2011]), the corpus of films by French-Jewish directors seems to me to have a specific purpose, reflecting debates among Jews about the place of both Jews and Muslims in France. In a context of increased violence against Jews in France, in which many perpetrators have identified as Muslim, some French Jews have decided that their place is no longer in France; they have emigrated to Israel.[3] Other Jews have remained in France, but have highlighted the dangers posed by anti-Semitism among young people of Middle Eastern or African descent (see for instance Alexandre Arcady’s 2014 film 24 Days, about the kidnapping and murder of Ilan Halimi). Some French Jews have sought to distance themselves from Muslims in other ways. In her 2014 book Rhinestones, Religion, and the Republic: Fashioning Jewishness in France, the anthropologist Kimberly Arkin described fieldwork she did among Sephardic Jewish teens outside of Paris. She reported that, out of fear that their North African origins might taint them in a France teeming with anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant sentiment, these young Jews proudly proclaimed their hate for Arabs, seeking to distinguish “Arab Jews from Arab Muslims.”[4]

The Franco-Jewish films on Muslim-Jewish relationships adopt a different approach. Paralleling the new scholarship by Mandel, Katz and others, a series of films by French-Jewish directors have rejected the notion that Muslims pose an inherent danger to Jews. These films respond to the current situation by affirming the possibility (and necessity) of Muslim-Jewish friendships. They also show an evolution in Franco-Jewish universalism. Whereas historically Jews were expected to hide their cultural particularities in public, the films affirm pluralism; they suggest that French Jews and Muslims need not hide their particularities if they are open to those of others.[5]

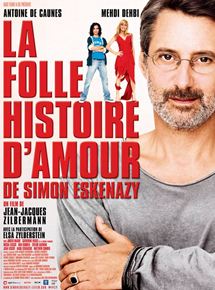

Many of the films in this corpus are available on English-subtitled DVDs and are well-suited for use in the classroom. For classes on contemporary France or on Muslim-Jewish relations, one of the best to show is Jean-Jacques Zilbermann’s 2009 romantic comedy He’s My Girl (La folle histoire d’amour de Simon Eskenazy). He’s My Girl is set in the 18th arrondissement, and offers a love letter to multiethnic Paris. At a time when French universalism has come under attack, the film champions republican inclusiveness; it suggests that diversity and particularism enrich Parisian life rather than threaten it. In addition to deconstructing stereotypes about religion and ethnicity in France, He’s My Girl offers a sensitive exploration of diverse LGBTQ identities.The film is also an excellent introduction to the films of Zilbermann, an accomplished film and stage director who has received surprisingly little scholarly attention.[6]

He’s My Girl centers on Simon, a gay, middle-aged Klezmer clarinetist who is internationally renowned. He is attractive, self-absorbed, and unable to commit to any of the men in his life. He loves living alone in Château-Rouge, amidst the neighborhood’s postcolonial diversity. Simon has a strained relationship with his mother Bella, a Holocaust survivor who is a French version of Woody Allen’s overbearing Jewish mothers. We also learn that Simon has an ex-wife, Rosalie, and a son, Yankele, who live in New York; Rosalie’s Hasidic family members, who disapprove of Simon’s homosexuality, have blocked him from spending time with Yankele. He’s My Girl’s plot revolves around Simon’s affair — and eventual romance — with Naïm, a handsome Algerian Muslim cross-dresser and cabaret performer. Simon wants young Naïm only for sex, but Naïm is genuinely attached to Simon and is eager to deepen their relationship. After Bella becomes ill and moves into Simon’s apartment, Naïm insinuates himself into the household as a female live-in health aide named Habiba. Habiba lovingly tends to Bella and the two become fast friends, to Simon’s shock.

Soon, Simon’s broken family life is being repaired, thanks to Naïm. Naïm/Habiba’s enjoyment of Bella’s company makes Simon reconsider his assumptions about his mother. Meanwhile, Rosalie and Yankele return from New York, announcing that they will live in Paris. Rosalie is engaged and wants Yankele not to feel displaced by her fiancé; she says she is ready for Simon to be a real dad to their son. Suddenly, however, Bella dies, which threatens Naïm’s place in Simon’s home. In his grief, Simon decides to be open about their relationship. When Naïm comes in male clothing to Bella’s shiva [a gathering to comfort mourners], and Rosalie asks whether they have known each other long, Simon declares tenderly, “Naïm is my best safeguard against gloom.”

The family unity is endangered, however, by someone who does not believe in universalism: Rosalie’s Hasidic father, Mordechai. While he has adjusted to Simon’s homosexuality, a “Muslim transvestite” is too much for him to bear. On Mordechai’s behalf, Rosalie’s fiancé tells Simon coarsely in English: “If you want to see your kid, you’re going to have to make a choice. That’s life for ya…. You’ve got to learn to make compromises.” A conflicted Simon breaks up with Naïm, claiming that it is about himself and not Yankele. But as the movie ends, Simon realizes that what he has with Naïm is not something tawdry or temporary.

Like other Franco-Jewish films about Muslim-Jewish relationships, He’s My Girl celebrates French pluralism, rather than a universalism in which differences must be hidden. Naïm need not give up his identity as an Arab to be accepted by Simon’s family. He freely uses terms like “Mazal tov” and “L’chaim” to build bridges with Jews. But he maintains his own political beliefs, as when he makes several jokes in sympathy with Palestinians. For his part, Simon teases Naïm about whether Algerian Jews got compensation when they were driven out after Algerian independence in 1962. The film suggests that while two people can come from different places and have divergent outlooks on Mideast politics, their humanity—and love itself— transcends labels about sexuality, politics and religion. Their differences enliven their relationship, rather than pull them apart.

The actors’work in the film also embraces boundary-crossing. Particularly moving is Mehdi Dehbi’s performance as Naïm. Dehbi, who happens to be straight, artfully embodies Naim’s heartaches and his evolving self-fashioning, as he adopts different female personas to sustain his relationship with Simon. Dehbi also starred in another Muslim-Jewish friendship film, Lévy’s Le fils de l’autre, as a young Palestinian who discovers he was actually born to an Israeli Jewish family and switched at birth. Mehdi has talked about how meaningful these roles have been to him as a human being and artist, in affirming that commonalities and relationships between human beings are more important than labels about identity.[7] A similar choice to cross boundaries in the film was made by Antoine de Caunes, the legendary French TV host who plays Simon. De Caunes is heterosexual and not Jewish, but he fully inhabits the role of Simon Eskenazy, klezmer musician. Elsa Zylberstein (who, mirroring the film, had in real life previously been Antoine de Caunes’ romantic partner) is an excellent Rosalie, who proves more open to Naïm than Simon expects.

He’s My Girl stands alone for viewing. However, instructors might pair it with other Muslim-Jewish relationship films by Franco-Jewish directors such as Karin Albou’s La Petite Jérusalem or Wedding Song. While celebrating Muslim-Jewish friendships, these films give more weight to the obstacles faced by such relationships than Zilbermann’s does. La Petite Jérusalem, set in modern-day Sarcelles, focuses on the illicit romance between Laura, a Tunisian-born Jewish university student, and Djamel, an Algerian Muslim; it shows how family prejudices disrupt their affair. Wedding Song offers a kind of meditation on the origins of Muslim antisemitism, as Albou imagines a way beyond current tensions. The film, set in Tunis in November 1942, focuses on the lifelong friendship between two sixteen-year-old girls, one Muslim and one Jewish. The film traces what happens to their bond when the Nazis invade North Africa; it suggests that tensions between Jews and Muslims are historically contingent and need not be permanent.[8]

Alternatively, He’s My Girl could be shown with its prequel, the 1997 romantic comedy L’homme est une femme comme les autres (Man is a Woman).[9] That humorous but bittersweet film includes many of the same actors as in He’s My Girl, with Antoine de Caunes as a much younger Simon, Judith Magre as Bella, and the young Elsa Zylberstein (then at the start of her real-life romance with de Caunes) as Rosalie. L’homme est une femme received some significant critical praise, and de Caunes received a César nomination for Best Actor. But, as Darren Waldron notes in Queering Contemporary French Popular Cinema: Images and Their Reception, the film had a very limited release. Waldron concludes that it focused on themes (presumably gay and Jewish ones) deemed to be of interest only to “a young urban population,” so it was not distributed widely outside of central Paris.[10]

Man is a Woman does not deal with universalism in the same way as He’s My Girl. Here, the romantic protagonists are both Jews who embrace the Ashkenazi musical culture of their ancestors. Nevertheless, the film raises other kinds of questions about identity and difference. Viewers who watch only He’s My Girl might presume that Simon realized he was gay while married to Rosalie and then got divorced. In fact, as Man is a Woman begins, Simon is already comfortable with his sexuality. His Holocaust survivor relatives urge him to get married, insisting that “we were almost exterminated” and that he is the only Eskenazy left to carry on the family name. Simon reminds them that he is gay and that they should not forget it. However, Simon’s uncle Solomon, the ultra-rich leader of Bank Eskenazy (a fictional kind of Rothschild), has decided that it’s time for Simon to stop “messing around” and to produce an heir. Solomon offers Simon 10 million francs – plus his mansion – if Simon will get married. Simon resists this offer, but Solomon cuts off Simon’s overdraft at Bank Eskenazy and soon has him locked out of his apartment. Bella, fully aware of her son’s sexual orientation but struggling financially, advises Simon to have a sham marriage, collect the money, and get divorced.

While Simon is deciding what to do, he discovers that he has a female suitor. Rosalie, a Franco-American Orthodox ingenue from Brooklyn, has fallen in love with his soulful clarinet playing. Though Rosalie is no longer as religious as her Hasidic family in New York, she is still a virgin waiting for the right man to marry. She sets her sights on Simon, and Bella convinces him to woo, and then divorce, her. Simon assumes that, because Rosalie is a woman, he will have no romantic interest in her. Despite his sexual orientation, however, he finds himself falling for her; Rosalie turns out to be, on the one hand, irritating, and on the other hand irresistibly lovable. Eventually, Simon realizes that he cannot switch off his attraction to men, breaking Rosalie’s heart and destroying her sunny disposition. But Man is a Woman, which at first seems to be a broad farce about a gay man pretending to be with a straight woman, takes seriously the idea that love can transcend labels.

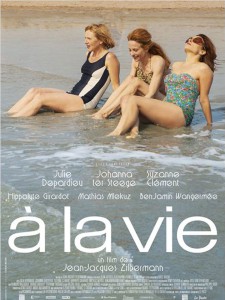

An added bonus in showing Man is a Woman alongside He’s My Girl would be the opportunity to highlight its references to the Holocaust, through Simon’s survivor relatives and through the vanishing musical traditions that Simon and Rosalie are trying to save. Some of Zilbermann’s other works deal with the legacy of the Shoah more directly. Zilbermann is the son of survivors and he addresses this in À la vie (To Life, 2014).[11] The film, starring Julie Depardieu, centers on three women who were “camp sisters” in Auschwitz, and who find each other 15 years after the end of the war. It is based on Zilbermann’s mother Irène’s relationships with fellow deportees; the DVD also contains Zilbermann’s earlier documentary Irène et ses soeurs (2002) that inspired À la vie.[12] Whereas the Holocaust is often invoked to guard against contemporary antisemitism, Zilbermann belongs to that Franco-Jewish Left that uses the Holocaust to argue against racism in general and to suggest solidarity with Muslims.[13]

Certainly, the twenty-first century has caused anxiety among French Jews. But like their counterparts among historians, a number of French-Jewish directors have looked toward the possibility of connections with their Muslim fellow citizens rather than emphasize histories of tension. He’s My Girl exemplifies this sentiment, while offering an accessible storyline and poignant performances.

Jean-Jacques Zilbermann, Director, La folle histoire d’amour de Simon Eskenazy [He’s MGirl], 2009, Color, 87 min, France, Agat Films & Cie, Arte France Cinéma, Bac Films. Available on DVD and, currently, for streaming on YouTube

NOTES

- Maud S. Mandel, Muslims and Jews in France: History of a Conflict (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014), 1 and passim; Ethan Katz, The Burdens of Brotherhood: Jews and Muslims from North Africa to France (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015). See also the landmark collection by Abdelwahab Meddeb and Benjamin Stora, eds., Histoire des relations entre juifs et musulmans: des origines à nos jours (Paris: Albin Michel, 2013), and History of Jewish-Muslim Relations: From the Origins to the Present Day (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013); and the essays in Esther Benbassa and Jean-Christophe Attias, eds., Juifs et musulmans: Une histoire partagée, Un dialogue à construire (Paris: Découverte, 2006).

- For more on this corpus of films (which also includes documentaries by filmmakers such as Camille Clavel, Yolande Zauberman and Simone Bitton), see Alyssa Goldstein Sepinwall, “Reimagining Jewish-Muslim Relations on Screen: French-Jewish Filmmakers and the Middle East Conflict,” in Zvi Jonathan Kaplan and Nadia Malinovich, eds., Re-examining the Jews of Modern France: Images and Identities (forthcoming Brill, 2016).

- See for instance Oren Liberman, “Au revoir and Shalom: Jews Leave France in Record Numbers,” CNN (January 25, 2016), available at http://www.cnn.com/2016/01/22/middleeast/france-israel-jews-immigration/.

- Kimberly A. Arkin, Rhinestones, Religion, and the Republic: Fashioning Jewishness in France (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014), 7. Arkin’s research methods have sparked some controversy among other scholars; see for instance the review by Andrea L. Smith in American Ethnologist 42, no. 3 (August 2015): 553-554.

- For a fuller explanation of this evolution, see Sepinwall, “Reimagining Jewish-Muslim Relations.”

- Zilbermann has been cited chiefly in works on queer cinema, which mention his 1997 film L’homme est une femme comme les autres. I have not found any articles or books devoted to his work.

- Interview by Alyssa Sepinwall with Dehbi, San Diego, February 2011.

- La Petite Jérusalem (2005), dir. Karin Albou, 96 mins., Kino Video, 2006, DVD ; and Wedding Song [Le chant des mariées] (2008), dir. Karin Albou, 100 mins, Strand Releasing, 2009, DVD. For further analysis of Albou’s work, see Sepinwall, “Sexuality, Orthodoxy and Modernity in France: North African Jewish Immigrants in Karin Albou’s La Petite Jérusalem,” in Lawrence Baron, ed., Modern Jewish Experiences in World Cinema (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2011), 340–47.

- L’homme est une femme comme les autres (1997), dir. Jean-Jacques Zilbermann, 100 min, Polygram, 1999, DVD (PAL Region 2 with English subtitles); also available in PAL Region 2 editions from Universal, 2002, and Millivres Multimedia, 2005.

- Darren Waldron, Queering Contemporary French Popular Cinema: Images and Their Reception (New York: Peter Lang, 2009), 264.

- See for instance interview with Zilbermann by Justine Boivin, “À La Vie : l’émouvant témoignage de Jean-Jacques Zilbermann,” Le journal des femmes (Nov. 26, 2014), available at http://www.journaldesfemmes.com/loisirs/cinema/1200132-a-la-vie-l-emouvant-temoignage-de-jean-jacques-zilbermann/.

- À la vie, dir. Jean-Jacques Zilbermann, 104 mins., France 3 cinéma/Elzevir Films/FranceTV distribution, 2015, DVD (PAL Region 2, no English subtitles); Irène et ses soeurs is also currently available on Vimeo (https://vimeo.com/25145015), accessed January 19, 2016. À la vie is a sensitive examination of the many ways that survivors continued to be affected by their experiences long after liberation. Some reviewers have seen it as plodding (and thus at odds with its title); its slow pace makes it less attractive for classroom use than Zilbermann’s other films. However, like the best new Holocaust films, the film offers precious insights about neglected aspects of survivors’ lives, such as the way that camp traumas affected their family lives for decades. À la vie also briefly explores the role of Holocaust survivors in reviving the Communist Party in France after the war, a subject mined more fully in Diane Kurys’s excellent Pour une femme (2013, For a Woman) and in Zilbermann’s 1993 comedy Tout le monde n’a pas eu la chance d’avoir des parents communistes (Not Everyone Was Lucky Enough to Have Communist Parents).

- On this tendency, see discussion in Sepinwall, “Reimagining Jewish-Muslim Relations” of Camille Clavel’s films; see also Esther Benbassa, The Jews of France: A History from Antiquity to the Present (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 189 – 190.