Richard S. Fogarty

University at Albany, SUNY

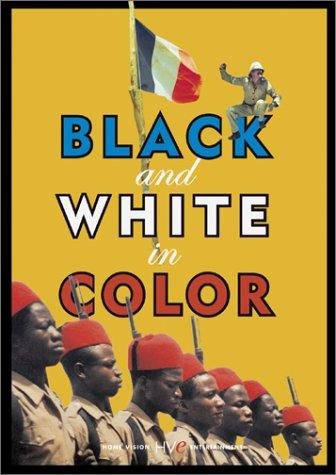

“Don’t you ever get excited anymore?” Posed to her bored and impotent husband on a hot tropical night in a remote outpost of the French empire in Africa in 1915, a woman’s question sets the stage for the upheaval that follows in Jean-Jacques Annaud’s Black and White in Color (Noirs et blancs en couleur). Her husband suffers from le cafard, the infamous, debilitating depression that the hot, dangerous, and lonely work of building and maintaining the empire imposed upon its European inhabitants. A minority in Europe itself, mostly among the urban, educated bourgeoisie, felt a different kind of lassitude in the face of modern life and its tensions, seeing deliverance and a welcome excitement in the outbreak of war in August 1914. The conflict soon reaches the small settlement where the Frenchwoman and her husband reside, and Annaud’s film skillfully brings together the two historical realities of war and colonialism to paint a darkly humorous portrait of the folly of both.

As the centenary years of the Great War get under way in 2014, there will no doubt be renewed interest in many aspects of the conflict. It is already clear, both from the direction of scholarly research and from increased public sensitivity to Europe’s colonial past, that the participation of the colonies in the conflict will get full attention. France, which in 1914 possessed the second-largest empire after Britain, relied on its colonies to contribute to the war effort. So the war resonated in France’s colonies, far from Europe, and this is worth remembering.

As the centenary years of the Great War get under way in 2014, there will no doubt be renewed interest in many aspects of the conflict. It is already clear, both from the direction of scholarly research and from increased public sensitivity to Europe’s colonial past, that the participation of the colonies in the conflict will get full attention. France, which in 1914 possessed the second-largest empire after Britain, relied on its colonies to contribute to the war effort. So the war resonated in France’s colonies, far from Europe, and this is worth remembering.

Almost forty years ago, Noirs et blancs en couleur did as good a job of linking the Great War to the colonial context as any artistic representation is likely to do in the next few years. Noirs et blancs en couleur employs satire and black humor to expose the injustices, absurdities, and violence at the heart of colonialism. Annaud’s 1976 film is set in a small, isolated colonial outpost in French Equatorial Africa (l’Afrique Équatoriale Française, or the AEF), and the action begins in January 1915. None of the French residents of Fort Coulais (fewer than a dozen) have heard from home in the last six months. This means, as the audience of course knows, that they are unaware that France has been at war with Germany since the beginning of August. Soon, news of the global war bursts in on this corner of the globe. Hubert Fresnoy, a young geographer, receives a package from France and opens it in the company of the other French residents. Extracting a newspaper, he exclaims in surprise and horror, “They have assassinated Jaurès!” While the committed socialist laments the murder of the pacifist leader of the French left, the others discover from other newspapers in the parcel that France is at war with Germany.

Fired with patriotism, all but Fresnoy immediately demand that the local French official, the bored, drunken, debauched Sergeant Bosselet, mobilize the fort and lead a martial expedition against the tiny German outpost in the neighboring colony (Kamerun) –this despite longstanding friendly relations between the two groups. What follows is a parody both of the war and French colonialism. The initial French expedition is a hastily organized (or, rather, disorganized) disaster, but the rest of the film follows the progress of Fresnoy away from his earlier internationalist pacifism and toward political, colonial, and military ambition. Though derided previously by the other French, he assumes command through the force of his personality and intelligence, qualities his compatriots notably lack. He then plans and leads a far better organized expedition, which also ends disatrously, though for different reasons. At the film’s end, British troops arrive to accept the surrender of the Germans, in accordance with an agreement worked out between France and England to divide German colonial territories. The disappointed French console themselves with the knowledge that they have at least retained control over their own territory and can now resume their old lives, oblivious of the pathetic ennui they had suffered before the war’s excitement.

In 1977, Noirs et blancs en couleur won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. The Oscar has ensured the longevity of the film’s reputation, but critical reception was initially tepid. French reviewers tended to be more generous, but American reviewer Roger Ebert was fairly typical in questioning whether the film was worthy of the prestigious award, opining that another foreign language entry that year, Cousin cousine, was a superior work of art. The French critics’ responses suggested that they possessed the necessary historical background to appreciate the film’s message, and that a fuller understanding of the colonial context and of the Great War was necessary in order to grasp the genuine value of the film.

The film pokes fun at France and its colonial project, and is therefore ripe for analysis by both scholars and students because its deployment of satire frees us from a tedious discussion (for which academics are all too notorious) of the film’s inaccuracies. It does not intend to portray events accurately, but to expose, through ridicule and exaggeration, some basic truths about colonial attitudes, so that we might understand the realities of French colonialism more vividly. For this reason Noirs et blancs en couleur works well with my students. They grasp the important themes that the film discusses, precisely because it makes its points in such an outsized, blunt, and darkly humorous fashion.

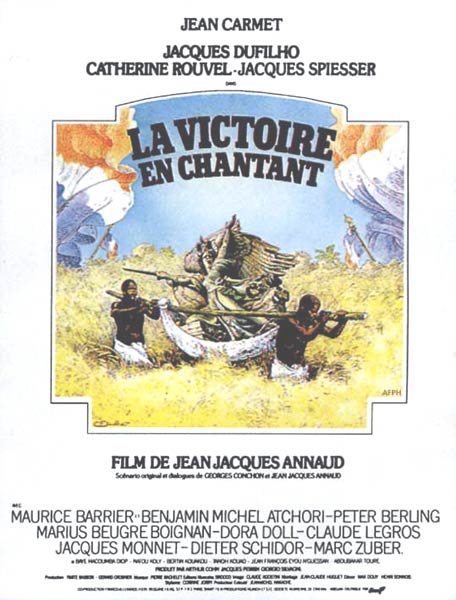

One key to the movie’s intentions is its title. Originally called La victoire en chantant, from the French Revolutionary hymn Chant du départ, the film was released in English as Black and White in Color, and rereleased in France after winning the Oscar as Noirs et blancs en couleur. Curiously, but significantly, this French rendering is not an exact translation of the English title. The French is plural, so “blacks and whites in color,” focusing squarely on the people in the film, their color and race. So reviewers who note that the film depicts a colonial situation that is anything but black and white are not off the mark, but it is not just the situation’s lack of clarity that stands out. Many of the “blacks” and “whites” are colorful characters, and the film seeks to depict them within the racial and colonial hierarchies that shaped their interactions and gave them meaning. Tellingly, the white French colonists are filmed in a variety of lurid hues that highlight their ridiculous pretentions.

La Victoire en chantant 14-18

The film’s original title is worth considering. The Chant du départ is, like the Marseillaise, a call to arms to defend the republic. The film opens with the song in the archaic (to our ears) style of the early twentieth century, while the credits roll against the backdrop of campy, colorized postcards from wartime France. These familiar, conventional images highlight the contrast with the war as it filters into the AEF. The contrast is clearest near the end of the film, when indigenous Africans, trained by the stern Fresnoy, sing the Chant du départ as they line up for review before the assembled white French colonists. The Africans sing lines that are not only ironic in the central African context, but absurd: “From the North to the South, the trumpet of war invites us to fight. When the Republic needs us, we must conquer or die. A Frenchmen must live for it, for it a Frenchman must die!”[1] Standing bare-chested and barefoot in the hot African sun, holding sticks instead of rifles, they describe a physical patrie that they will never see and that will never be theirs. They sing of defending a republic that does not count them as citizens with rights, but as subjects with obligations. France asked them to die in the Great War without ever viewing them as “French.”

One of the French colonialists’ claims — “This is my home! (Ici, je suis chez moi!)” — is repeated throughout the film. In the first, farcical attack on the German outpost, the French residents accompany the native African force under the command of Sergeant Bosselet in order to watch the battle. Dressed in their Sunday best, the colonists imagine they are crossing the Rhine, rather than a small stream, in order to plant the French flag on “German” soil. The dim shopkeeper Paul Réchampot leads this charge, just like the French armies charged into Alsace and Lorraine in 1914 to reclaim those lost territories from Germany. His even dimmer brother is the flag bearer, but he fails to negotiate the stepping-stones that dot the stream, plunging right into the water and soaking his fine European shoes and pants. The invasion is off to an inauspicious start. When the expedition suffers a humiliating reverse in the field, much like French forces in August 1914, the colonists’ enthusiasm quickly fades. The spectators’ fancy picnic is ruined as they are forced to flee with the retreating French forces.

One of the French colonialists’ claims — “This is my home! (Ici, je suis chez moi!)” — is repeated throughout the film. In the first, farcical attack on the German outpost, the French residents accompany the native African force under the command of Sergeant Bosselet in order to watch the battle. Dressed in their Sunday best, the colonists imagine they are crossing the Rhine, rather than a small stream, in order to plant the French flag on “German” soil. The dim shopkeeper Paul Réchampot leads this charge, just like the French armies charged into Alsace and Lorraine in 1914 to reclaim those lost territories from Germany. His even dimmer brother is the flag bearer, but he fails to negotiate the stepping-stones that dot the stream, plunging right into the water and soaking his fine European shoes and pants. The invasion is off to an inauspicious start. When the expedition suffers a humiliating reverse in the field, much like French forces in August 1914, the colonists’ enthusiasm quickly fades. The spectators’ fancy picnic is ruined as they are forced to flee with the retreating French forces.

The film’s perspective on colonial space is equally ironic: French Africa is not only French, but “France,” even while the French Republic refuses to accept the Africans as citizens. Réchampot expresses outrage at Fresnoy’s first steps toward dictatorship, declaring, “This is a republic!” which of course it is not, especially from the indigenous standpoint. The neighboring German colony is shown as all bustle and business, its indigenous soldiers well-trained and speaking decent German. One assimilated African soldier declares proudly, “A German must never fear fatigue!” In contrast, the French outpost is quiet and lethargic, the lowly sergeant in charge spends his time trimming his toenails, and the indigenous soldiers speak the distinctive pidgin of Africans in the French army (known as langue tirailleur) and relax playing checkers. A soldier reminds his comrade to count the kings, but the other responds, “This is a Republic, kings don’t count here!” Both crack up at this bon mot.

Throughout, the native Africans, more peanut gallery than Greek chorus, offer the film’s most devastating commentary. At the very end of the film, they watch in disgust as the French and Germans, formerly at each other’s throats (with deadly consequences for the Africans), laugh convivially after the surrender of the German camp to the British. Fresnoy’s African concubine, acquired in his dictatorial days, spits in anger, while one African man waiting on the Europeans shakes his head and says, simply, “White people….” Another responds, “I know….” Africans, even while victims of the folly, racism, and violence of Europeans, see through the pretensions of their colonial masters, sometimes exploiting it (as do Fresnoy’s indigenous adjutant, wielding power even over the whites, and Fresnoy’s concubine, to whom the French women must curtsy), sometimes enduring it (as do the Réchampots’ shop assistant, beaten and insulted by the two idiot brothers, and soldiers pressed into service), sometimes evading it (as does the African who kneels in prayer, repeating “Allahu Akbar,” outside a church, until he sees the two priests arriving and so puts away his prayer mat and crosses himself). Thus is the film able to raise questions about the hypocrisies and inconsistencies of French colonialism that historians have been exploring with increasing sophistication.

Fort Coulais’ two bumbling priests provide ready fodder for parody in some of the most famous scenes in the film. In one, they listen to the singing of the Africans carrying them in sedan chairs, and one sighs with delight, “Oh, how I love this song.” The subtitles reveal that it is about the strangeness of white people and how their feet stink. In another scene, the priests tell an audience of potential converts that the Christian god is more powerful than any other, because he enables his followers to ride a bicycle. Not only can the priests ride, their African acolyte also possesses this occult power. The priests are contemptuous of indigenous culture, exchanging native animist icons for Christian ones, haggling and driving hard bargains. They burn most of what they get, judging the African pieces unworthy even of a charity shop at home…even in the provinces.

The resident French have no respect for religion, mirroring the ferocious Church-State battles of the militantly secular Third Republic, but the priests are equally hypocritical and unjust in upholding the French “civilizing mission.” Even the priests’ attack of conscience, when faced with Fresnoy’s use of torture to gain recruits for his army, remains shallow and ineffective. Torture evokes the French army’s notorious tactics during the Algerian war, linking all colonialism with abuse, moral bankruptcy, and the most egregious violations of the ostensible principles of the republic. Fresnoy is unimpressed by the priests’ intervention, noting that they had not bothered to help the wounded natives after the first, disastrous battle. Ignominously, they ran away like the rest, leaving Fresnoy alone to minister to their needs.

Fresnoy’s character is the most complex in the film, and his contradictory attitudes and actions lie at the heart of the story. He struts around like Napoleon, with his hands clasped behind his back, while he calmly assesses the military situation after the defeat. He takes over the camp, since he is the only one with any ideas about what to do. There is a Robespierre-like calmness and ruthlessness about him as he intones the Jacobin justification for the Terror of 1793-94, repurposed for the Great War and the French colonial empire. He tells the priests, “I didn’t ask for this war,” but makes clear he knows how to wage it.

But the real parallel is to the fictional Mr. Kurtz, the terrifying perversion of European morality depicted in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Like Conrad’s Kurtz, Fresnoy is changed by the colonial context from that rare European who believes notions of white superiority and native inferiority to be unfounded, into a tyrant who uses natives and Europeans alike to pursue power and his own peculiar notions of what is right. Fresnoy’s commitment to enlightened egalitarianism is limited from the start: he condemns the conventional idea of African savagery by remarking that the natives “are not far from meriting the name of men.” Yet he alone wants to explain the consequences of joining the French army to potential recruits (the other French prevent him from doing so), and he alone cares for the wounded. He also refuses the obvious advances of a Frenchwoman, taking up with an African woman instead.

But Fresnoy’s actions also betray the racism and exploitation typical of French males in the empire. Their native lovers were but “temporary wives,” discarded when the men left the colony, having satisfied their sexual cravings and desire for the exotic. We want to sympathize with Fresnoy, but his cold disregard and increasing megalomania make him increasingly remote, an extreme version of the darkness and corruption at the heart of colonial rule. Faced with a shortage of volunteers, he visits the chief of a nearby village and menacingly informs him that he will get no mercy from the Germans, since his village participated in the initial attack. The chief is reluctant to enlist his own men, but he jumps at the chance to capture and force into service men, whom he calls “savages,” from the surrounding savannah region, men Fresnoy knows are in hiding. Yet the chief’s enthusiasm is feigned, and he rounds up a mere 20 recruits, instead of the required 100. The 20 are sick and frail, clearly unsuitable for service. He does not embrace the French cause and does not want to offend his neighbors, even the “savages” of the savannah. This is when Fresnoy resorts to intimidation and torture, with the moronic and brutal Jacques Réchampot as his heavy. The recruits arrive with their hands bound and ropes around their necks. It is worth noting that nothing about these scenes is unrealistic, from the quotas and pressure exercised on local elites, to the selection by those elites of men unfit for service, to the forced recruitment and lines of men tied together with rope. Such means, combined with milder coercion and even sometimes with a degree of more or less genuine voluntarism, allowed France to recruit around half a million colonial troops to fight in the French army between 1914 and 1918.

The presentation of the war captures some of its historical realities. The skirmishes in the AEF are a microcosm of the larger war, where initial French reverses are followed by long-range planning and a more systematic approach. One of the priests, an aggrieved and patriotic Alsatian, expresses the war’s virulent nationalism when he decries the “German mentality” that makes the enemy essentially different from the French. Fresnoy declares “War is too important to be left to shopkeepers,” referring to the colonists who bullied Sergeant Bosselet into a rash attack on the Germans. This echoes Georges Clemenceau’s famous declaration that war was too important to be left to the generals, when he became both Prime Minister and Minister of War in 1917. The conflict in the AEF descends into stalemate, complete with muddy trenches, when, against everyone’s expectations, Fresnoy’s second attack stretches on futilely into the rainy season. The African troops come down with respiratory diseases, suffering and dying, replicating the experience of many Africans who really did serve in France during the war.

When the British arrive, they are, to everyone’s surprise and consternation, commanded by a person of color, an Indian with the rank of captain. His troops are African. Fresnoy refuses to speak English to Captain Kapoor, so an African interpreter informs the assembled French colonists that the German post under attack will fall under British jurisdiction. The Germans will surrender to Kapoor, an insult to the French who have been fighting them for so long. After the surrender, Fresnoy goes for a stroll with his German counterpart, Kraft. They look almost exactly alike, are the same age, and are university graduates. Fresnoy notes the irony of his pre-war socialism yielding to warmongering, unaware that most European socialists had similarly betrayed their pacifist internationalism and answered their nations’ calls to arms in 1914. The German responds, “Ich auch,” before correcting himself and saying, “Me too,” in French (one mustn’t offend French linguistic pride). The two go off into the sunset whose rays form red, white, and blue bars recalling the Union Jack. British power will eclipse that of both the defeated Germans and the French, whose victory in 1918 really was Pyrrhic. The colonists declare in jubilation, “We beat them!” but as in Europe, the cost was high, allied help was essential, and French power was damaged.

At the movie’s end Africans from the French camp approach some British African soldiers, observing that their uniforms are very chic. A British soldier responds, “Haven’t you ever seen a decent army, you French savages?” Once again, there is the irony of Africans calling other Africans “savages,” but the real point is that France’s colonial project has failed. If the ostensible goal was to assimilate supposedly inferior “races,” then the Germans and the British have done a much better job. France could not accomplish its allegedly noble aim of a “civilizing mission.” The film’s clear message is that despite victory and a colonial empire that stretched around the globe, France was not really successful at either war or empire.

Jean-Jacques Annaud, Director, Black and White in Color (Noirs et blancs en couleur), 1976, Color, 90 min., Côte d’Ivoire, France, West Germany, Switzerland, Artco-Film, France 3 Cinéma, Reggane Films.

Currently a subtitled version is posted on YouTube, here.

- This is how the subtitles have it. The French, from the first verse, is, “Et du nord au midi la trompette guerrière/A sonné l’heure des combats…. La République nous appelle,/Sachons vaincre ou sachons périr;/ Un Français doit vivre pour elle,/Pour elle un Français doit mourir.”