Chris Millington

Swansea University

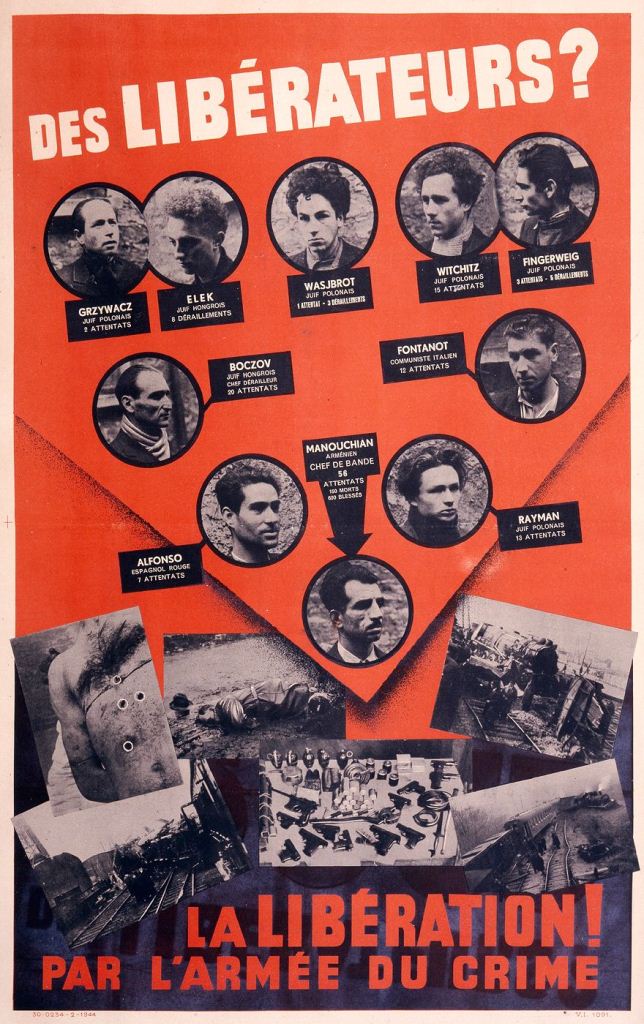

Robert Guédiguian’s L’armée du crime (2009) is a story of resistance and collaboration in wartime France. Its focus is the Manouchian group, a network of migrants led by Armenian poet Missak Manouchian and affiliated to the immigrant worker section (Main-d’oeuvre immigrée – MOI) of the Francs-tireurs et partisans (FTP) resistance movement. The film covers the period between the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 (and the beginning of active communist resistance in France) to the arrest of Manouchian and his comrades in November 1943. The final scene depicts a humiliating photo-shoot in which the resisters are paraded in front of press photographers. Using these photographs, the occupation authorities would later produce the infamous “Affiche Rouge,” a poster featuring ten members of the group that was distributed throughout France with the legend “Liberation by the army of crime.”

As a tool for teaching, the film has much has much to offer students of Vichy France. Film has played an important role in historical approaches to Vichy, both reflecting, and contributing to, changing historical trends. Along with Robert Paxton’s 1972 academic work on Vichy France, Marcel Ophuls’ documentary The Sorrow and the Pity (1971) is widely credited with having begun to break down the orthodox history of the war years, which held that the French had, in their vast majority, supported the resistance. Louis Malle’s Lacombe Lucien (1974) and Au revoir les enfants (1987) have become staples of undergraduate classes as much for what they reveal about the context in which the films were produced as about the war years themselves. Likewise, L’armée du crime – and, one might add, the 2010 film La rafle [1]– is a product of its time. It is useful for illustrating to students the diversity of experience of the war years, and it is symptomatic of a context in which public readiness to confront previously taboo subjects has never been higher.

As a tool for teaching, the film has much has much to offer students of Vichy France. Film has played an important role in historical approaches to Vichy, both reflecting, and contributing to, changing historical trends. Along with Robert Paxton’s 1972 academic work on Vichy France, Marcel Ophuls’ documentary The Sorrow and the Pity (1971) is widely credited with having begun to break down the orthodox history of the war years, which held that the French had, in their vast majority, supported the resistance. Louis Malle’s Lacombe Lucien (1974) and Au revoir les enfants (1987) have become staples of undergraduate classes as much for what they reveal about the context in which the films were produced as about the war years themselves. Likewise, L’armée du crime – and, one might add, the 2010 film La rafle [1]– is a product of its time. It is useful for illustrating to students the diversity of experience of the war years, and it is symptomatic of a context in which public readiness to confront previously taboo subjects has never been higher.

Having recently taught the film, I would like to share some thoughts on what it showed students about resistance and collaboration in wartime France. I used the film in conjunction with Robert Paxton’s book on Vichy France, John Sweets’s Choices in Vichy France (1986), and Paula Schwartz’s work on women in the communist resistance and the maquis. The focus of the class was therefore very much on the methods and motivations behind resistance and collaboration, as well as how each phenomenon has been portrayed. I usually show L’armée du crime with La rafle since the two films offer some interesting points of contrast. Moreover, both were produced in the last few years and thus have a modern look to them, something that I have found to be important in capturing the imagination of students who might be initially reluctant to view foreign-language cinema.

The film is useful in demonstrating to students the various forms that resistance could take, from spreading the word (Marcel Rayman and his friend Henri Krasucki drop leaflets from the rooftop of a Parisian building; Thomas Elek chalks communist symbols on the wall of his school), to the killing of German soldiers. We hear, too, radio reports of train derailments and other acts of sabotage. The film depicts female involvement in the resistance: women transport weapons in suitcases, bags and prams, while they help to produce and disseminate anti-German propaganda too. It amply illustrates for students the activities of the partisanes described by Schwartz.

Students found the political motivations of the resisters difficult to discern. While there are clues to the communist affiliation of the group – for example, in one scene the resisters quietly hum the communist anthem the Internationale – these are perhaps too vague for the average student to notice, and usually require explanation. In any case, the political motivations behind the most startling acts of resistance in the film are obscured by more personal concerns. While Thomas Elek plants a bomb in a collaborationist bookshop hidden inside his copy of a Marxist tome, his action is apparently spurred by the anti-Semitic attacks he and his family had suffered. Marcel Rayman assassinates his first German soldier after learning that his father has been deported. When Missak Manouchian throws a grenade into a troop of German soldiers, it is with an image of his dead brother in mind. The resisters in the film seem to be motivated by personal rather than ideological concerns.

Repression and persecution in the film are unmistakably French. French police are shown torturing the resisters and they guard a bus transporting Jews. Frenchmen hang an anti-Jewish poster on the Eleks’ restaurant and later we see French paramilitaries smashing up the café. We learn that the internment camp at Beaune-la-Rolande (also depicted in La rafle), where Marcel’s father is being held, is guarded by gendarmes. Unlike La rafle, where sympathetic officers are shown warning Jews of the impending raid, the police in L’armée du crime display no such compassion. Inspector Pujol, the police inspector for the arrondissement in which the resistance is based, although accepting the promotions offered to him, does not seem to be acting out of self-interest. Nonetheless, Pujol does offer to put Monique Stern in touch with her parents after they are arrested in the round up of Jews, but it is a lie intended to extract sexual favours from her. The arch-collaborator in the film is Superintendent David, head of the Special Brigade tasked with hunting down foreign ‘”terrorists.” The depiction of David is rather one-dimensional. The viewer is led to conclude that he is an out-and-out sadist: during discussions with Inspector Pujol, he is shown handling a birch, while later in the film a German officer congratulates the Superintendent on his torture techniques.

As for the “ordinary” French – those neither directly involved in resistance nor collaboration – students found little evidence that life under the Occupation was particularly unpleasant. An early scene showing German soldiers at the Trocadéro brought to mind Jean Texcier’s advice to the occupied French in 1940. Yet in L’armée du crime there is little evidence that the population has heeded Texcier’s warning that the Germans are not tourists. The Occupiers hold open-air concerts for French audiences, play soccer in the park, and socialise with French women. As for low-level collaboration, the concierge Madame Boulin denounces the resister M. Forestier to the police. Her reason? Forestier is a “wop.” Her action stands in stark contrast to the concierge in La rafle, who shouts a warning to Jewish residents when the police arrive.

As for the “ordinary” French – those neither directly involved in resistance nor collaboration – students found little evidence that life under the Occupation was particularly unpleasant. An early scene showing German soldiers at the Trocadéro brought to mind Jean Texcier’s advice to the occupied French in 1940. Yet in L’armée du crime there is little evidence that the population has heeded Texcier’s warning that the Germans are not tourists. The Occupiers hold open-air concerts for French audiences, play soccer in the park, and socialise with French women. As for low-level collaboration, the concierge Madame Boulin denounces the resister M. Forestier to the police. Her reason? Forestier is a “wop.” Her action stands in stark contrast to the concierge in La rafle, who shouts a warning to Jewish residents when the police arrive.

Finally, the historical accuracy of the film offers another subject of discussion, which can be initiated by Guédiguian’s postscript. At the conclusion of the film, on-screen text informs the viewer that the director has “modified certain facts” and adjusted the chronology, measures deemed “necessary” in order that this “true story becomes a modern legend.” Indeed, in the pages of Le Monde, historians Sylvain Bouloque and Stéphane Courtois have criticized the hagiographical style of Guédiguian’s history of the Manouchian group. Furthermore, they claimed that Guédiguian had constructed “a vision contrary to historical truth.” Disobedience in the group – of which Marcel Rayman’s seemingly impulsive assassinations of German soldiers is the best illustration – is exaggerated, as are the seemingly anti-Stalinist convictions of its members. In the film, the treachery of Monique Stern leads to the arrest of the group yet Bouloque and Courtois credit assiduous police work rather than betrayal for the resisters’ demise. Not only does L’armée du crime therefore illustrate to students the methods and motivations behind resistance and collaboration, it offers the chance to discuss the broader question of the use of film to illustrate history.

In sum, L’armée du crime’s is a bleak tale of heroism and sacrifice. It stands in contrast to La rafle. In the latter, both the survival of the child protagonist and his friend (who somehow escaped from a train bound for the East) and the selfless action of nurse Annette Monod – with whom the audience should presumably identify –provide a form of redemptive closure. French characters in L’armée du crime do not display a similar sympathy with the resisters; in fact French resisters are practically absent from the film. The film begins and ends with a roll call of the Manouchian group during which the viewer is struck both by the “foreignness” of the names and the realisation that these resisters did not survive the war years. Guédiguian’s film thus serves to remind viewers of the desperate sacrifices not only of the French but of the exiles and immigrants who had looked to it as a land of refuge.

Robert Guédiguian, Director, L’armée du crime [Army of Crime], Color, 2009, 139 min., France, Agat Films & Cie, Studio Canal, France 3 Cinéma.

- See Julian Jackson’s review of La rafle in Volume 1, Issue 1 of this bulletin, and of Lacombe Lucien by Richard Vinen in Volume 2, Issue 1.