Roxanne Panchasi

Simon Fraser University

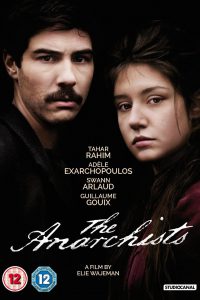

The trailer for Elie Wajeman’s Les Anarchistes promises one hundred minutes of intrigue, beauty, and romance set in the streets, cafés, and apartments of a fin-de-siècle Paris alight with revolutionary ideas and activity. This was an era that saw the proliferation of new forms of literary and artistic expression, spectacular entertainments, visionary technologies and fantasies. It was also a time of anxiety: fear of cultural decadence and degeneration, of threats to republican order and bourgeois values, of politically radical individuals and groups, in France and throughout Europe.

The film’s opening sequence is a keynote for the drama ahead. Our female lead, Judith (Adèle Exarchopoulos), sits in a darkened room, responding to questions posed by her friend, Marie-Louise (Sarah Le Picard): “Will you tell me about your life before… about your memories?” Judith offers glimpses of her story: a childhood desire to become a teacher, her arrival in the French capital, her work as a seamstress to save enough money to pursue her ambitions. It was in the city’s workshops that Judith learned what exploitation was, became enraged by all she witnessed and experienced, and began to dream of another world, another way of life. “Why did you become an anarchist?” asks Marie-Louise. “One might think it was hate, but it was love,” Judith responds. “Love made me an anarchist.”

Sex, lies, triangulated (b)romance, guns, explosives—Les Anarchistes has it all. An intimate thriller, both suspenseful and sentimental, Les Anarchistes is the story of Jean Albertini (Tahar Rahim), a low-ranking police officer tasked with infiltrating an anarchist cell. Throughout the film, locations stand in for class difference, the tension between state power and popular resistance, and Jean’s personal journey. After receiving his initial assignment at police headquarters, Jean moves into a modest studio where he meets regularly with his hard-nosed superior, Gaspard (Cédric Kahn). Taking up work in a Parisian factory, Jean first encounters “Biscuit” (Karim Leklou), one of his targets. The two exchange stories, they laugh, and Jean lets drop a provocative line at the right moment: “There are one or two things I wouldn’t mind setting fire to.” Biscuit introduces Jean to the group’s leader, Elisée Mayer (Swann Arlaud), and to the ultra-militant Eugène (Guillaume Gouix), who will never entirely trust the newcomer. After Jean proves himself loyal during a police raid of a local bar where the group drinks, recites poetry, and debates politics, Elisée welcomes Jean to the fold. Despite Eugène’s suspicions, Jean is invited to stay with the group in the bourgeois apartment where they squat together. Its rooms become the site of his affective overhaul and this new family melts his cold, orphaned, duplicitous heart.

Biscuit introduces Jean to the group’s leader, Elisée Mayer (Swann Arlaud), and to the ultra-militant Eugène (Guillaume Gouix), who will never entirely trust the newcomer. After Jean proves himself loyal during a police raid of a local bar where the group drinks, recites poetry, and debates politics, Elisée welcomes Jean to the fold. Despite Eugène’s suspicions, Jean is invited to stay with the group in the bourgeois apartment where they squat together. Its rooms become the site of his affective overhaul and this new family melts his cold, orphaned, duplicitous heart. A fraternal bond develops and deepens between our hero and Elisée, and Jean falls for Elisée’s companion, Judith. As Jean’s involvement with the group intensifies, the suspense builds. Will Jean’s true identity be revealed? Will he and Judith get caught? Will his superiors discover his growing sympathy for his friends and their beliefs?

A fraternal bond develops and deepens between our hero and Elisée, and Jean falls for Elisée’s companion, Judith. As Jean’s involvement with the group intensifies, the suspense builds. Will Jean’s true identity be revealed? Will he and Judith get caught? Will his superiors discover his growing sympathy for his friends and their beliefs?

Beyond the walls of their beautiful lair, the gang moves through the city. To support themselves and “the cause,” they loot graves and commit a series of break-ins. At first, their crimes are petty and no one gets hurt, but their actions become more violent as the story unfolds. One night, they threaten a bourgeois owner who catches them stealing from his home. The stakes soar as they begin working with an armed Austrian group and decide to hold up a bank. The plan goes sideways. Biscuit is shot and dies. Soon after, Jean finds Elisée and Eugène preparing a bomb. Grief over the loss of their friend has confirmed their commitment to violent action. Torn between his attachment to Elisée, his passion for Judith, and his mission, Jean waivers at moments, even considering abandoning his assignment at one point. Ultimately, however, he betrays his comrades and his lover. In a final confrontation with the police, Elisée shoots himself after crying out “Vive l’anarchie!” Judith is devastated when she learns who Jean really is as the other members of the gang are arrested. She escapes capture, fleeing to the United States. When a senior officer asks Jean in a closing scene whether he has become an anarchist, Jean hesitates at first. The pained expression on his face reveals his ambivalence. The experience has clearly changed him, but still he responds, “No.”

Torn between his attachment to Elisée, his passion for Judith, and his mission, Jean waivers at moments, even considering abandoning his assignment at one point. Ultimately, however, he betrays his comrades and his lover. In a final confrontation with the police, Elisée shoots himself after crying out “Vive l’anarchie!” Judith is devastated when she learns who Jean really is as the other members of the gang are arrested. She escapes capture, fleeing to the United States. When a senior officer asks Jean in a closing scene whether he has become an anarchist, Jean hesitates at first. The pained expression on his face reveals his ambivalence. The experience has clearly changed him, but still he responds, “No.”

“C’est pas un film politique,” Elie Wajeman told a journalist when Les Anarchistes premiered at the Semaine de la Critique at the Festival de Cannes in 2015.[2] Wajeman explained that the idea for the film came from his desire to tell an “infiltration” story, a story of love and betrayal. His decision to set the film in the late-nineteenth century was “artistic” rather than political. Indeed, political questions and stakes are more incidental than fundamental to Les Anarchistes. Lines delivered throughout the film resonate with anarchist writings and rhetoric. There is talk of class inequality and state corruption, of the legitimacy and/or necessity of violence to the struggle, of the tensions between anarchism, syndicalism, and democratic politics. And there are repeated, vague references to individual liberties and a society without rules. But the film’s plot is driven by infatuation and sexual yearning rather than politics. The moral of this story is that politics are an interpersonal affair. Jean is charmed and seduced by the gang’s camaraderie and lifestyle, by the feeling of home their company brings. In melancholic Elisée, he finds a brother, while in Judith, he finds an outspoken and fervent lover.

“C’est pas un film politique,” Elie Wajeman told a journalist when Les Anarchistes premiered at the Semaine de la Critique at the Festival de Cannes in 2015.[2] Wajeman explained that the idea for the film came from his desire to tell an “infiltration” story, a story of love and betrayal. His decision to set the film in the late-nineteenth century was “artistic” rather than political. Indeed, political questions and stakes are more incidental than fundamental to Les Anarchistes. Lines delivered throughout the film resonate with anarchist writings and rhetoric. There is talk of class inequality and state corruption, of the legitimacy and/or necessity of violence to the struggle, of the tensions between anarchism, syndicalism, and democratic politics. And there are repeated, vague references to individual liberties and a society without rules. But the film’s plot is driven by infatuation and sexual yearning rather than politics. The moral of this story is that politics are an interpersonal affair. Jean is charmed and seduced by the gang’s camaraderie and lifestyle, by the feeling of home their company brings. In melancholic Elisée, he finds a brother, while in Judith, he finds an outspoken and fervent lover.

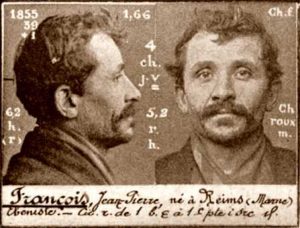

Wajeman and his team did their historical homework in terms of set and costume design, and various character and plot elements are clearly inspired by figures such as Emile Henry, who bombed the Café Terminus in Paris in 1894, or the infamous “Bonnot gang,” active in the capital from 1911 to 1912. In Les Anarchistes, the archives make cameo appearances. During the film’s opening credits, late nineteenth-century sepia-tone photos taken by the French police tether this fiction to the lives and acts of real-life men and women. Jean reads the police files of his targets, as well as that of his own father, a Communard, now dead. Historical names are dropped here and there: Victor Hugo (Jean is a fan) and Mikhail Bakunin (a quick citation helps Jean to establish his radical “cred”). And then there is Elisée, whose father was also a Communard. Could there be a better moniker for the leader of an anarchist gang in fin-de-siècle France?[3]

Readers of works such as John Merriman’s The Dynamite Club, or Richard Parry’s The Bonnot Gang may not find Wajeman’s fiction objectionable per se, but neither will they find any compelling insight or analysis regarding the lives and significance of historical anarchists. Those familiar with Kristin Ross’s recent work on the Paris Commune and its “centrifugal” effects, including anarchist thinkers and writers such as Elisée Reclus and Peter Kropotkin will gain no exciting new perspective here on the links between the Commune and later developments, or how the ideas and texts of anarchists past might serve as resources for political activists in the present.[4]

Would Les Anarchistes be a good or appropriate film to watch with students? Well, I should preface my response to this question by making clear that my response to this question is almost always, “Yes, given the right context.” There are a number of legitimate reasons to show a film in a course, just as there might be any number of possible reasons to assign a written primary or secondary source. In my courses, I regularly present films (newsreel or archival footage, documentary, fiction) from different periods as texts that can reveal much about when and where they were produced, and about those who made and viewed them. In addition to whatever productive conversation they might spark about the letter or spirit of the historical actors and events represented onscreen, these films are also, necessarily, primary sources. Whatever their historical accuracies or inaccuracies, they offer insights into how that moment might (mis)understand the past.

In other words, I can imagine showing Les Anarchistes in a course, and I can imagine the film’s historical and political content serving as the basis for a meaningful conversation with my students that might pursue the following questions: Why a film about anarchists in 2015? What does this film’s representation of nineteenth-century culture and politics say about the meanings of that past in contemporary France? What do the film’s inclusions and exclusions tell us about the memory-status of anarchism, or about the currency of radical political ideals at a time of new forms of French political extremism, activism, and fear, from far left to far right?

Wajeman did not set out to make a film about the past that would resonate with the present, in the way that Merriman’s book, for example, considers the relationship of fin-de-siècle anarchism to present-day forms of terrorism. The director has admitted, however, that the nineteenth-century anarchists’ way of thinking and being seemed more familiar and “modern” to him as he researched the project.[5] At moments, Les Anarchistes moves intentionally between the historical and the contemporary. Marie-Louise’s interviews of individual members of the group have a distinctly recent docu-drama feel. Wajeman’s anachronistic soundtrack selections disrupt the careful replication of the private and public spaces of the nineteenth-century French capital. During the film’s opening credits, Ken Boothe’s “Lonely Teardrops” (1966) tugs at the viewer’s heartstrings. Somewhere in the middle of the action, our anarchists pillage the homes of wealthy Parisians while stealing kisses, celebrating, and taking photographs, all to the sound of the Kinks singing “I Go to Sleep” (1965). The final sequence of the film returns to Judith in voice-over. As she reads a letter she has written Jean from overseas, archival footage of European immigrants arriving in America flickers onscreen. Judith utters her last lines: “Vive la révolution sociale! Vive l’anarchie!” Fade to black, followed by final credits that roll to the sound of Johnny Clarke’s “Declaration of Rights” (1976).

The most obvious recent example of filmic play with the French past that Les Anarchistes brings to mind is Sofia Coppola’s 2006 Marie-Antoinette.[6] Although they treat different historical periods and diverge in a number of ways, the two projects share some key elements: a youthful, star-studded cast, and a careful attention to period detail, with anachronistic interruptions. These, of course, are far more exaggerated in the case of Coppola’s film, a whimsical mash-up of early-twenty-first century nostalgia for both the 1780s and the 1980s. But while Marie-Antoinette made a number of French historians uncomfortable, even annoyed, its “failures” (intentional and otherwise) with respect to the “real” eighteenth century seemed—and still seem—to me to be very good reasons to screen it in my own seminar on the French Revolution.[7] As I have argued elsewhere, anachronism is not, in and of itself, antithetical to productive historical or political engagement with the past.[8] Provocative in a number of ways, Coppola’s film works for me as an effective point of entry to a discussion of historical and contemporary mythologies and fascination with the Ancien Régime, Marie-Antoinette, and all things “French Revolution.”

“The revolution…will not star Natalie Wood and Steve McQueen,” sang Gil Scott-Heron in 1971.[9] In Les Anarchistes, however, the revolutionaries are, indeed, played by the hottest, freshest faces of le cinéma français actuel. Starring Tahar Rahim as Jean, Adèle Exarchopoulos as Judith, and a collection of other hip talent, the film is nothing if not visually appealing. Whether working in a factory, escaping a police raid, suffering from illness, facing arrest, dying in the street, or in a stairwell, these anarchists always look so, so good. Moving through a series of beautiful décors, in perfectly tailored period costumes that never quite convey the exploitation and inequities they rail against—in poems, speeches, and forms of direct action—these young French actors are relentlessly attractive and stylish.

The film is perhaps a symptom then, of a millennial version of what Tom Wolfe referred to as “radical chic,” what happens when fashion takes up the revolution, emptying its images and symbols of their original political meanings or intentions.[10] Except that Wolfe’s radicals were the contemporaries of the wealthy and privileged elites who sought the cachet of their company. The place of history and politics in Les Anarchistes reminds me, in some ways, of “Commune de Paris,” a contemporary boutique located at 19, rue Commines in Paris’s 3rd arrondissement. Anchored around a line of carefully crafted clothing and accessories inspired by France’s revolutionary history, the shop carries a range of must-haves for the “lifestyle anarchist” in all of us: a “Louise (Michel) et Gustave (Courbet)” t-shirt (50 euros), a silk scarf that reads “PARIS BRÛLE T-IL?” (90 euros), “Commune de Paris” eau-de-cologne, (130 euros), and an “Anarchy” tote (55 euros) are just a few examples.[11] In Les Anarchistes, the engagement with the French past and its struggles feels less surface than these wares, but not by all that much. Class struggle and consciousness are subordinated to personalities and relationships, while political ideals and acts become dialogue and plot twists. History in Wajeman’s film is, first and foremost, a vibe, un feeling, a set of nostalgic aesthetic and decorative choices, from the fin-de-siècle setting to the sounds of the 1960s/70s that play in the background. In the end, the love that makes these anarchists anarchists feels more like a crush than solidarity.

Elie Wajeman, Director, Les Anarchistes (2015), France, Color, 101 min, 24 Mai Productions, France 2 Cinéma, Mars Films.

NOTES

- *: The phrase (“With fists of love) is a line from a Léo Ferré’s 1969 song, “Les Anarchistes.”

- Interview with Elie Wajeman, La Semaine de Critique, Festival de Cannes 2015, 14 May, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4KTDJVDeJEw (accessed 15 March 2017).

- A geographer and writer, Elisée Reclus was a well-known French anarchist who participated in the Paris Commune of 1871.

- For a brilliant recent discussion of Reclus’s thought within a broader analysis of the Commune’s “centrifugal effects,” see Kristin Ross’s Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune (New York: Verso Books, 2015). For a quick overview of anarchism’s French history in which Reclus figures importantly, see George Woodcock’s “Anarchism in France,” chapter 10 of Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements (Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 2004), 230-274. See also John Merriman, The Dynamite Club: How a Bombing in Fin-de-Siècle Paris Ignited the Age of Modern Terror (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Company, 2009) and Richard Parry, The Bonnot Gang: The Story of the French Illegalists, 2nd edition (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2016).

- See Interview with Elie Wajeman, op. cit.

- Marie-Antoinette. Directed by Sofia Coppola. Los Angeles: Columbia Pictures, 2006.

- See the H-France discussion launched by historian Judith Miller’s 29 May 2006 post, “Sofia Coppola’s Marie-Antoinette,” H-France Archives. https://lists.uakron.edu/sympa/arc/h-france (accessed 15 March 2017); See also, Jennifer Milam’s essay, “Imagining Marie Antoinette: Cultural Memory, Coolness and the Deconstruction of History in Cinema,” French History and Civilization: Papers from the George Rudé Seminar, 4, 2011, 45-53.

- See my article, “If the Revolution Had Been Televised: The Productive Anachronisms of Peter Watkins’s La Commune (Paris, 1871)” in Rethinking History, 10, no. 4 (December 2006): 553-571.

- See the lyrics to Gil Scott-Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” released as a single with Flying Dutchman Productions in 1971.

- See Tom Wolfe, Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers (new York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1970).

- See the fashion line’s website: https://www.communedeparis1871.fr (accessed 15 March 2017).