V. Hunter Capps

University at Buffalo, SUNY

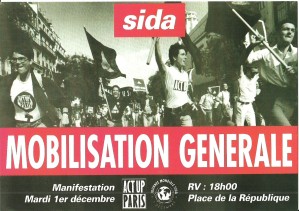

Originally premiering at the Cannes Film Festival in May of 2017 where it won the Grand Prix, 120 battements par minute rapidly garnered attention both inside France and in the United States. The focus of the film is the grassroots political organization ACT UP Paris (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) and its members as they react to government apathy in the face of rising death tolls and the medical establishment’s slow efforts at finding a cure. To contextualize France a bit further, despite having decriminalized homosexuality in 1982, Socialist president François Mitterrand, who was in office from 1981, when the crisis emerged, until 1995, a year before life-saving medication became available, did not order an assessment of the AIDS crisis, and it was because of such political indifference that ACT UP Paris was born.

ACT UP Paris was formed in 1989, two years after its American counterpart held its first demonstration in March of 1987. The film is set in the early 1990s when the director Robin Campillo joined the group. The date is extremely important because it situates the film before 1996 when effective medical treatments became available as a triple combination antiretroviral therapy, otherwise known as HAART,[1] still used today, and that transformed HIV from a death sentence into a chronic but livable condition.

Robin Campillo depicts both the meetings behind ACT UP’s actions and the emotional roller-coaster that governed many of these intense exchanges. This pointedly French, existential style consists of prolonged scenes that make the viewer feel as if the drama unfolding between ACT UP’s members is not so much fictitiously staged as authentic. One of the first scenes in the film consists of one of the organization’s leaders explaining the basic rules and tenets of ACT UP to some newcomers. What is ACT UP? Where do we decide what actions to take? How do we speak to each other? Are you ready to be perceived as HIV positive regardless of your status? As the members file in, other group leaders lay out the evening’s agenda and its specific subjects. For the duration of this meeting, the members engage each other in a respectful yet nonetheless fierce dialogue concerning a recent protest that did not go according to plan. This cinematic aesthetic contributes to enhancing the viewer’s experience, by generating a remarkable empathy. Indeed, the plight of those living with and around HIV in the late 80s and early 90s was rather extraordinary.

To represent a time when friends and family were dying in droves and gay sex was made out to be a one-way ticket to heaven, this cinematographic aesthetic feels especially salient. Members of ACT UP are portrayed as engaging in robust rhetorical exchanges that aptly illuminate the struggles of the time. Sean, played by Nahuel Pérez Biscayart, is HIV positive and at one point in a heated debate shouts out his quickly depleting T-cell count. He represents the one side of the epidemic and of ACT UP members in particular, who knew that they had very little time left and thus called for more intense and immediate medical and political action.

To represent a time when friends and family were dying in droves and gay sex was made out to be a one-way ticket to heaven, this cinematographic aesthetic feels especially salient. Members of ACT UP are portrayed as engaging in robust rhetorical exchanges that aptly illuminate the struggles of the time. Sean, played by Nahuel Pérez Biscayart, is HIV positive and at one point in a heated debate shouts out his quickly depleting T-cell count. He represents the one side of the epidemic and of ACT UP members in particular, who knew that they had very little time left and thus called for more intense and immediate medical and political action.  Indeed, during a protest at the pharmaceutical company Melton Pharm, Sean angrily reminds an employee shaken up by their fake-blood splatter that he and his friends do not have time to wait for their trial results; they are all dying.

Indeed, during a protest at the pharmaceutical company Melton Pharm, Sean angrily reminds an employee shaken up by their fake-blood splatter that he and his friends do not have time to wait for their trial results; they are all dying.

Alongside them, leaders of ACT UP Thibault and Sophie, played by Antoine Reinartz and Adèle Haenel, argue for more “rational” and pacifist approaches. The former is a rough, composite character, drawn mainly from Didier Lestrade, the first president of ACT UP Paris. The latter is also a composite character that pays homage to the presence of lesbians in the fight against AIDS, something not often seen in American depictions of the crisis.

Alongside them, leaders of ACT UP Thibault and Sophie, played by Antoine Reinartz and Adèle Haenel, argue for more “rational” and pacifist approaches. The former is a rough, composite character, drawn mainly from Didier Lestrade, the first president of ACT UP Paris. The latter is also a composite character that pays homage to the presence of lesbians in the fight against AIDS, something not often seen in American depictions of the crisis.

Other scenes in the film help to contribute to its historical accuracy. In one meeting, a member uses a projector to explain the inner workings of a new and promising protease inhibitor as it interacts with the virus and a healthy human cell, foreshadowing the advent of HAART. This scene serves two functions. First, it is an accurate representation of how members of ACT UP educated themselves in the latest scientific findings in order to be up to speed with current treatments and the responses of bureaucratic bodies. Second, the viewers learn at the same time what is assuredly not common knowledge about HIV, how it interacts with the body and the drugs that keep people alive. Although this might seem mundane, since it is not the fake blood splattered on a wall or a dramatic disruption of church services during real life ACT UP protests, this scene helps to teach viewers about the less exciting aspects of how the epidemic unfolded. After all, staying informed and dispelling ignorance were always at the forefront of ACT UP’s concerns, and on this front the film more than exceeds expectations.

An extended scene shows Sean engaging in sex with Nathan (Arnaud Valois), an HIV negative member of ACT UP with whom Sean will eventually pursue an amorous relationship despite his not so promising future. The scene consists of an open conversation about the usage of condoms for both oral and anal exchanges wherein Sean expresses his preferred usage of latex. Once more, the audience sees a substantially authentic, non-romanticized depiction of what sex of the time looked like: informed, open, and engaged but nevertheless haunted by the specter of HIV. Once more, the scene functions both aesthetically for the purposes of the film’s portrayal of the issues surrounding gay sex as well as informatively exposing the audience to the realities of those living at the time. What is more, one learns that safe sex was critical to the ACT UP movement. Keep in mind, it was illegal to advertise condoms in France until 1988, and the government failed to provide information about prevention, one of ACT UP’s principal goals.

One scene, however, reveals what might be a big critical faux pas in the film. This is a scene where the audience is shown actual footage of a real ACT UP protest, spliced with the hospitalization and the quick death thereafter of a sympathetic minor character. The young man is a history student, and he reflects on the similarities between the February Revolution of 1848 that spawned the short-lived Second Republic, and the revolution in outlook that was developing in France regarding AIDS. He wishes his ashes to be returned to his family, a point whose relevance we will see later in the film. This relates directly to the political and historical nature of the response to AIDS in France. The eventual collective response of ACT UP, modeled after a longstanding American LGBTQ community and protest tradition,[2] was delayed at a significantly high price. Scholar Jean-Pierre Boulé has pointed out that at the height of the crisis, the casualty rate in Paris alone was three times that of the entire United Kingdom.[3] By and large, France suffered worse from the epidemic than any of its European neighbors, all of whom had organized prevention campaigns as early as 1983 while France’s first official campaign started in 1987. Moreover, France’s lack of testing of blood donors contributed to the overall negligent oversight of HIV/AIDS, as blood transfusions were discovered to be infected. This was the situation to which ACT UP ultimately responded.[4]

I see this scene as exposing the fundamental division in France between the traditional universalist view of rights (that to its credit did allow for the early passing of anti-discrimination laws as well as decent funding for research) and a more communitarian approach. The film shows in its recreation of ACT UP’s meetings how its French members were open to an Anglo-American-inflected model of community and their insistence that such communities be recognized. Indeed, the film’s opening scene has one leader define ACT UP specifically as “a group founded in the gay community specifically to defend the rights of people with AIDS.” Moreover, chief among the goals of ACT UP, both in America and in France, was to define AIDS as a political crisis that necessitated political solutions. Another group depicted in the film, AIDES, was a less radical community-based not-for-profit organization that worked to organize its own prevention campaigns. It was founded by Michel Foucault’s lover, originally as an extension of the anti-colonial engagement of the famous gay French philosopher, as a response to the lack of action on the government’s part. With the scene of the dying history student in mind, the vision the film proposes of France’s political response, as well as its way of historicizing the epidemic, become somewhat tendentious.

I see this scene as exposing the fundamental division in France between the traditional universalist view of rights (that to its credit did allow for the early passing of anti-discrimination laws as well as decent funding for research) and a more communitarian approach. The film shows in its recreation of ACT UP’s meetings how its French members were open to an Anglo-American-inflected model of community and their insistence that such communities be recognized. Indeed, the film’s opening scene has one leader define ACT UP specifically as “a group founded in the gay community specifically to defend the rights of people with AIDS.” Moreover, chief among the goals of ACT UP, both in America and in France, was to define AIDS as a political crisis that necessitated political solutions. Another group depicted in the film, AIDES, was a less radical community-based not-for-profit organization that worked to organize its own prevention campaigns. It was founded by Michel Foucault’s lover, originally as an extension of the anti-colonial engagement of the famous gay French philosopher, as a response to the lack of action on the government’s part. With the scene of the dying history student in mind, the vision the film proposes of France’s political response, as well as its way of historicizing the epidemic, become somewhat tendentious.

ACT UP, unlike AIDES, was an intensely political organization whose birth and presence spoke to the utter urgency of the times. This means that we must take into account the political climate that allowed for HIV to explode in the Hexagon. A literature was emerging that questioned more than the actions of the Socialist government and the larger French model of universalism. Its principal representative was a journalist, Frédéric Martel, himself a member of the Socialist party and an open advocate of universalism, whose mainstream appeal came from the fact that he was a gay man essentially attacking gay men for being too paranoid to get tested, a theory among others that has since been debunked by scholars.[5] One should remember that in the early days of the crisis, when still so little was known, gay men were rightly suspicious of mandatory testing, especially in the hands of a medical establishment that had hitherto pathologized queer people and their sex acts. Moreover, the gay community in France, whose members are shown as fiercely bonded through their common existential plight in the film, did not exist prior to ACT UP per se, since such community identity was treated as a challenge to the integrity of the universalist model. Indeed, the contemporary French gay community, especially in Paris, emerged from the historical queer tradition of which ACT UP was an integral part, as bonds were forged in the midst of untimely death, government indifference, and shared political solidarity.

The longing for community is demonstrated throughout the film in scenes of members of ACT UP dancing the night away in clubs where strobe lights flash on and off giving the audience glimpses of the moving and touching bodies that cannot help but come into contact with each other, alluding to the pivotal role of disco in early 80s gay culture.[6] At one point, the camera focuses on floating particles catching glints of light in the air that make them visible. The camera zooms in, this time to the microscopic level, where airborne microbes interact. At a time when the smallest infection could potentially mean hospitalization or even death, this scene stands out as emblematic of the constant risk to those with an autoimmune disorder and, ultimately, how unavoidable exposure really was. The fight for dignity and political recognition, existed alongside a ferocious will to live. Despite death and suffering, a solidarity was forged in these communities despite the risk of exposure to both microbial threats and to each other. Contact, desire, sex, touch, and proximity were all matters in which those affected by HIV were caught, and instead of shying away, many bravely marched forward, insisting on living despite many urging them not to. Jean-Marie Le Pen, the infamously far right French politician and father to Marine Le Pen, once proposed that HIV positive individuals be tattooed and quarantined. In the face of such discrimination, an emphasis on living becomes a radical act itself. The scene of ACT UP’s members proudly and jubilantly dancing in skirts with pom-poms in the gay pride parade comes to mind as well.[7]

The longing for community is demonstrated throughout the film in scenes of members of ACT UP dancing the night away in clubs where strobe lights flash on and off giving the audience glimpses of the moving and touching bodies that cannot help but come into contact with each other, alluding to the pivotal role of disco in early 80s gay culture.[6] At one point, the camera focuses on floating particles catching glints of light in the air that make them visible. The camera zooms in, this time to the microscopic level, where airborne microbes interact. At a time when the smallest infection could potentially mean hospitalization or even death, this scene stands out as emblematic of the constant risk to those with an autoimmune disorder and, ultimately, how unavoidable exposure really was. The fight for dignity and political recognition, existed alongside a ferocious will to live. Despite death and suffering, a solidarity was forged in these communities despite the risk of exposure to both microbial threats and to each other. Contact, desire, sex, touch, and proximity were all matters in which those affected by HIV were caught, and instead of shying away, many bravely marched forward, insisting on living despite many urging them not to. Jean-Marie Le Pen, the infamously far right French politician and father to Marine Le Pen, once proposed that HIV positive individuals be tattooed and quarantined. In the face of such discrimination, an emphasis on living becomes a radical act itself. The scene of ACT UP’s members proudly and jubilantly dancing in skirts with pom-poms in the gay pride parade comes to mind as well.[7]

As usual, the French bring something to the table that no one else can. The sentimentality of the film is by no means cheap, and when it delivers it carries just the right amount of weight. In the film’s climax, Sean, who has by now forged a relationship with Nathan, is clearly dying and asks Nathan to assist him in committing suicide. In the middle of the night, Nathan frantically and apprehensively injects Sean with a substance that will bring his suffering to an end. The next day, as friends from ACT UP pour into the apartment to mourn Sean’s loss, another lengthy scene unfolds as Sean’s mother and a friend help undress and dress again the twenty-six–year-old’s now lifeless body. The indignity of this disease is put on full display as Sean’s corpse is maneuvered into a fresh set of clothes while the camera moves around his body, including his eyes that have been taped shut and his diaper. The presence of this seemingly banal component, an adult diaper, functions to bring yet another realistic touch to the film. The viewer is not spared any of the uncomfortable details about this disease and the effects it has on the body. Unlike the final scene of Philadelphia where Tom Hanks, on the verge of HIV-related death, slowly and dramatically removes his oxygen mask to muster a smile for Denzel Washington, 120 battements par minute lets the presence of death slowly enter and linger in the minds of the viewers, drawing uncomfortable attention to the extent of the injustices of the epidemic.

As usual, the French bring something to the table that no one else can. The sentimentality of the film is by no means cheap, and when it delivers it carries just the right amount of weight. In the film’s climax, Sean, who has by now forged a relationship with Nathan, is clearly dying and asks Nathan to assist him in committing suicide. In the middle of the night, Nathan frantically and apprehensively injects Sean with a substance that will bring his suffering to an end. The next day, as friends from ACT UP pour into the apartment to mourn Sean’s loss, another lengthy scene unfolds as Sean’s mother and a friend help undress and dress again the twenty-six–year-old’s now lifeless body. The indignity of this disease is put on full display as Sean’s corpse is maneuvered into a fresh set of clothes while the camera moves around his body, including his eyes that have been taped shut and his diaper. The presence of this seemingly banal component, an adult diaper, functions to bring yet another realistic touch to the film. The viewer is not spared any of the uncomfortable details about this disease and the effects it has on the body. Unlike the final scene of Philadelphia where Tom Hanks, on the verge of HIV-related death, slowly and dramatically removes his oxygen mask to muster a smile for Denzel Washington, 120 battements par minute lets the presence of death slowly enter and linger in the minds of the viewers, drawing uncomfortable attention to the extent of the injustices of the epidemic.

As Sean’s friends congregate in the living room with Sean’s mother, one of them reads a short eulogy he has written that mentions Sean’s determination to make known the extent of the ravages of the epidemic. Sean, he says, who headed the prison subcommittee “spoke for faggots, addicts, prostitutes, those in prison. . .” and yet again the film pays proper historical homage to the manner in which this fight took place. Despite the sentimentality of Sean’s passing, the tragedy that was AIDS is not sanitized or reduced to the struggle of one or a few and the audience is forced once more to confront the reality of where and how this epidemic devastated minority populations. His friends make it clear that Sean’s memory will live on in the form of ACT UP persisting in the battle for acknowledgment, recognition, and justice for all those affected by HIV.

The film comes to a quick yet robust close that succinctly expresses the complicated manner in which all the issues behind the AIDS epidemic are interconnected. Nathan, having just lost Sean, asks Thibault to stay with him later that night to which Thibault candidly asks if they are going to have sex. As the sex scene between the two begins, so too does a final protest in which members of ACT UP infiltrate an insurance company’s gala and toss Sean’s ashes onto the ornately displayed banquet food. This powerful, political funeral was a common tactic used in real life by ACT UP in France and America. As the members of ACT UP shout and whistle at the participants in the gala, the lights begin to flash strobe-like, linking the scene to the earlier ones in the nightclub. This renders the scene of intense political protest and the scenes of communal enjoyment nearly indistinguishable. The setting does ultimately move to an actual nightclub scene, juxtaposed with the still-ongoing sex scene where Nathan abruptly begins to cry. As the music begins to fade, only the faint beeps of a heart monitor can be heard until finally all that remains is silence, blackness. Roll credits.

The film comes to a quick yet robust close that succinctly expresses the complicated manner in which all the issues behind the AIDS epidemic are interconnected. Nathan, having just lost Sean, asks Thibault to stay with him later that night to which Thibault candidly asks if they are going to have sex. As the sex scene between the two begins, so too does a final protest in which members of ACT UP infiltrate an insurance company’s gala and toss Sean’s ashes onto the ornately displayed banquet food. This powerful, political funeral was a common tactic used in real life by ACT UP in France and America. As the members of ACT UP shout and whistle at the participants in the gala, the lights begin to flash strobe-like, linking the scene to the earlier ones in the nightclub. This renders the scene of intense political protest and the scenes of communal enjoyment nearly indistinguishable. The setting does ultimately move to an actual nightclub scene, juxtaposed with the still-ongoing sex scene where Nathan abruptly begins to cry. As the music begins to fade, only the faint beeps of a heart monitor can be heard until finally all that remains is silence, blackness. Roll credits.

Douglas Crimp, an original member of ACT UP and scholar on AIDS discourse, has aptly noted how art and textual criticism were fundamental in the fight against AIDS.[8] 120 battements par minute depicts the AIDS crisis neither as an object of spectacle nor of overwrought sentimentality. It stays true to the spirit of ACT UP and the issues faced by those deep in the trenches, dealing respectfully with the movement’s narrative as well as refusing to hide the uglier side of the early plague days. In fact, this final scene is a perfect example of why the film is a pedagogically efficient tool from which anyone can learn about the AIDS phenomenon. There is an inextricable and deeply intimate relationship binding the human condition on display. Sex and death, life and protest, politics and pleasure are interwoven in a way that challenges widely accepted misconceptions. Seeing the characters respond to this tempest, the audience is afforded a glimpse into the heart of this struggle when HIV/AIDS challenged the social fabric.

Robin Campillo, Director, BPM (Beats per Minute)/120 battements par minute, France, 2017, Color, 143 min, Les Films de Pierre, France 3 Cinéma, Page 114, Memento Films Production, FD Production

NOTES

- Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy allowed for the successful suppression of the viral load in the body as well as allowing for the replenishment of once-depleted CD4 white blood cells.

- Pre-dating even the Stonewall riots of 1969, a type of zap itself, the “zap” was a form of direct political action that was harnessed by early gay liberation movements. They targeted and highlighted discriminatory people or places. They influenced but also evolved with the emergence of ACT UP. Their favorite tactic was “die-ins” where members would all lie down on the pavement before being apprehended by the authorities.

- Jean-Pierre Boulé, HIV Stories: The Archaeology of AIDS Writing in France, 1985-1988 (Liverpool, EN: Liverpool University Press, 2002), 11.

- For further reading on HIV and the French blood supply, see: Michael J. Bosia, “Written in Blood: AIDS Prevention and the Politics of Failure in France.” Perspectives on Politics 4, No.4 (2006): 647-653.

- For further reading on the prevailing scholarship, see: James N. Agar. “Queer in France: AIDS Dissidentification in France.” In Queer in Europe, 57-70. Burlington: Ashgate Publish Ltd., 2011. Michael J. Bosia. “’Assassin!’ AIDS and Neoliberal Reform in France.” New Political Science 27, no. 3 (August 2006): 291-308. Jean-Pierre Boulé, HIV Stories: The Archaeology of AIDS Writing in France, 1985-1988 (Liverpool, EN: Liverpool University Press, 2002). David Caron, AIDS in French Culture: Social Ills, Literary Cures (Madison WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001). My Father and I: The Marais and the Queerness of Community (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009). The Nearness of Others: Searching to Tact and Contact in the Age of HIV (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2014). William J. Poulin-Detour, “French Gay Activism and the American Referent in Contemporary France.” The French Review 78, no. 1 (October 2004): 118-25. Murray Pratt, “Getting it from Noise and Other Myths: AIDS and Intellectuals in France.” Paragraph 35, no.2 (2012): 181-196.

- For further reading on the nightclub as a naturally democratic space see: Guillaume Dustan, Je sors ce soir (Paris, FR: P.O.L., 2013).

- It is worth noting that the tradition of gay pride and the parades that accompany it come from the American Stonewall Riots of 1969, which are considered to be the catalyst for modern gay rights movements. ACT UP NY, and by extension ACT UP Paris, mobilized and utilized gay pride celebrations to revive the zap tradition to focus attention on both HIV/AIDS and the struggle for broader political, cultural, and social recognition for queers.

- Douglas Crimp, “AIDS: Cultural Analysis, Cultural Activism.” In October 43. (Winter 1987).