Emma Gilby

University of Cambridge

Tired of the vacuous backstabbing and insincerity of the theatrical world, ex-actor Serge Tanneur (Fabrice Luchini) has “pris sa retraite”: retired and retreated to an inherited home on the Ile de Ré, off the coast of La Rochelle. Unshaven, dressed in shapeless fisherman’s sweaters, with a house decorated in some indeterminately unfashionable era and a leaking septic tank, he finds himself increasingly out of place even here. As the film constantly reminds us, the Ile de Ré is now one of France’s most desirable holiday locations, with property prices on the island exceeding those in Paris. Off-season, the place is largely empty: its houses done up, made over and sold as second homes to wealthy city-dwellers (at one point, a back-lit jacuzzi fashioned from a stone feeding trough provides a perfect symbol of this transformation). The director of photography, Jean-Claude Larrieu, does a tremendous job of capturing the dulled ambience of the Ile de Ré in winter: all immense skies and endless dunes. Into this unseasonal wildness descends the slick, sophisticated Gauthier Valence (Lambert Wilson), complete with bouffant hair-do and fabulously impractical coat.

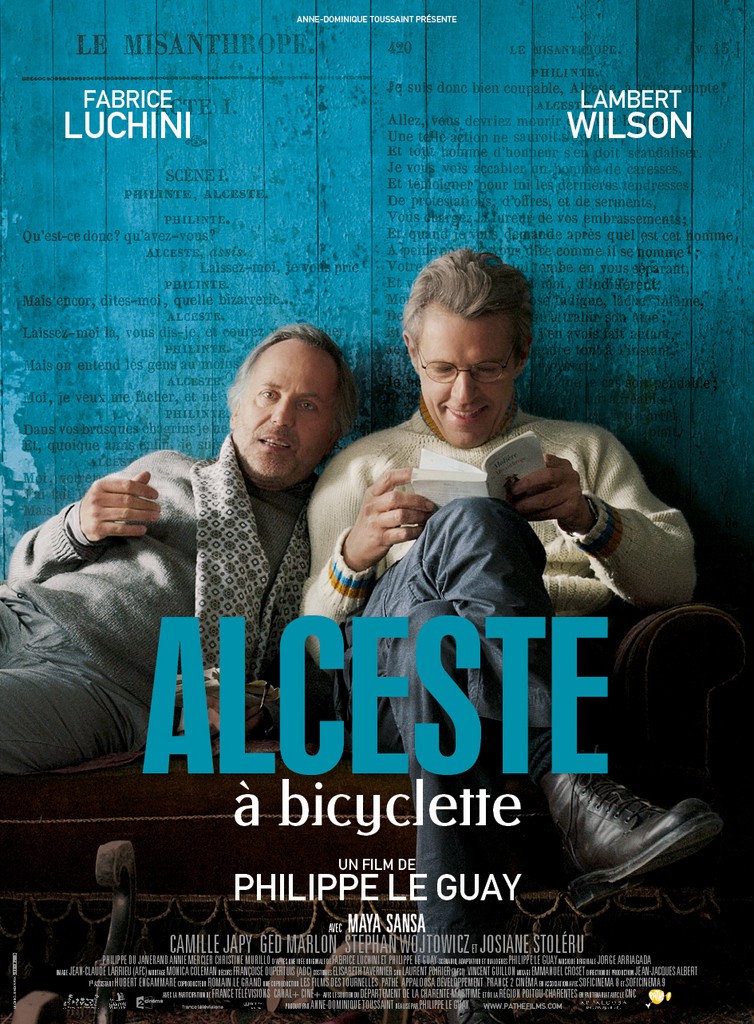

Gauthier is an old friend of Serge, but his life has taken a very different path. He now plays the role of an absurdly successful doctor in a daytime soap, Docteur Morange – Docteur Morange being the kind of man who is “capable de sauver un patient avec un couteau en plastique en pleine tempête de neige.” Artistic principles have been put aside in favour of the cushioning comforts of income and popularity. He wants, though, to return to the Parisian stage, and he wants Serge with him. His vision is of a new production of Molière’s classic, Le Misanthrope, and he needs Serge’s declamatory brilliance to make it work (Fabrice Luchini is renowned in France, incidentally, for his fine recitals of classical verse). The two men will work so closely together that they will be able to alternate the characters they play, taking on the roles of Alceste and Philinte in turn. It will be “du jamais vu”: a whole new way of thinking about the relationship between the two men. Director Philippe Le Guay’s conceit is, of course, to take the misanthropic Serge and the more open Gauthier and map modern onto classic in numerous, flexible ways. Serge initially refuses; but Molière calls to him, and he grants Gauthier a few days to see if the plan has any potential. We proceed to the first of very many readings of the play’s opening dialogue.

Gauthier is an old friend of Serge, but his life has taken a very different path. He now plays the role of an absurdly successful doctor in a daytime soap, Docteur Morange – Docteur Morange being the kind of man who is “capable de sauver un patient avec un couteau en plastique en pleine tempête de neige.” Artistic principles have been put aside in favour of the cushioning comforts of income and popularity. He wants, though, to return to the Parisian stage, and he wants Serge with him. His vision is of a new production of Molière’s classic, Le Misanthrope, and he needs Serge’s declamatory brilliance to make it work (Fabrice Luchini is renowned in France, incidentally, for his fine recitals of classical verse). The two men will work so closely together that they will be able to alternate the characters they play, taking on the roles of Alceste and Philinte in turn. It will be “du jamais vu”: a whole new way of thinking about the relationship between the two men. Director Philippe Le Guay’s conceit is, of course, to take the misanthropic Serge and the more open Gauthier and map modern onto classic in numerous, flexible ways. Serge initially refuses; but Molière calls to him, and he grants Gauthier a few days to see if the plan has any potential. We proceed to the first of very many readings of the play’s opening dialogue.

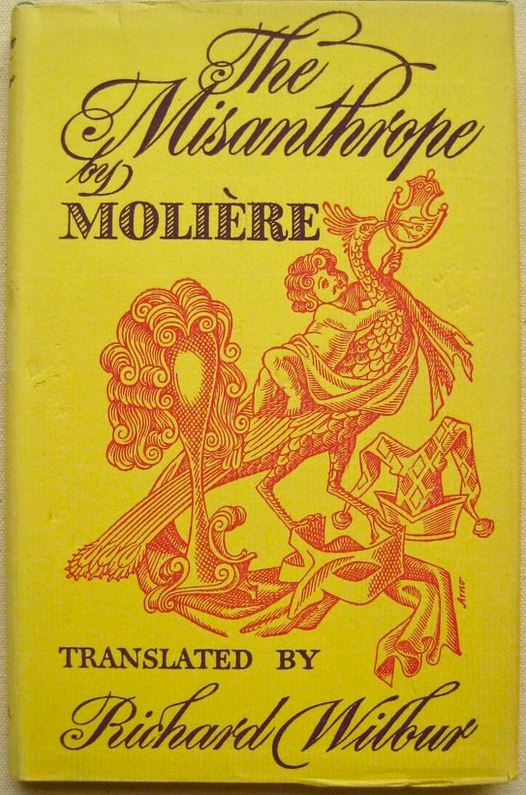

Act 1, scene 1 of Le Misanthrope is one of the most renowned exchanges in all of seventeenth-century French comedy. In the play, Alceste is taken to task by the phlegmatic, kind-hearted Philinte, who is the perfect embodiment of the seventeenth-century honnête homme. The quality of honnêteté, here, does not mean a straightforward “honesty,” but in some ways its opposite: an ability to fit in skilfully with whatever one’s social situation demands: (“Mais quand on est du monde, il faut bien que l’on rende / Quelques dehors civils que l’usage demande.”) Philinte, then, is a raisonneur figure: a figure who generally performs the comic function of directly opposing a foolish protagonist, expressing the social norms from which that protagonist diverges. As his name suggests, he is an excellent friend, offering frank and thoughtful advice. In the play, the scene has various focal points: Philinte’s greeting of a man he doesn’t really know; Alceste’s and Philinte’s contrasting attitudes to politesse and Alceste’s general tendency to separate himself off from the world, seeing insincerity all around; a lawsuit in which Alceste is embroiled; and finally, Alceste’s desire to have a private conversation with Célimène, with whom he is bizarrely and hopelessly in love. Alceste responds angrily both to Philinte’s advice and to its attendant suggestion of friendship, in a line that is repeated again and again in the film as Serge and Gauthier rehearse: “Moi, votre ami? Rayez cela de vos papiers.” This bilious volatility is perfectly mirrored in Serge’s own unpredictable attitudes: will he or won’t he finally agree to perform with Gauthier?

Act 1, scene 1 of Le Misanthrope is one of the most renowned exchanges in all of seventeenth-century French comedy. In the play, Alceste is taken to task by the phlegmatic, kind-hearted Philinte, who is the perfect embodiment of the seventeenth-century honnête homme. The quality of honnêteté, here, does not mean a straightforward “honesty,” but in some ways its opposite: an ability to fit in skilfully with whatever one’s social situation demands: (“Mais quand on est du monde, il faut bien que l’on rende / Quelques dehors civils que l’usage demande.”) Philinte, then, is a raisonneur figure: a figure who generally performs the comic function of directly opposing a foolish protagonist, expressing the social norms from which that protagonist diverges. As his name suggests, he is an excellent friend, offering frank and thoughtful advice. In the play, the scene has various focal points: Philinte’s greeting of a man he doesn’t really know; Alceste’s and Philinte’s contrasting attitudes to politesse and Alceste’s general tendency to separate himself off from the world, seeing insincerity all around; a lawsuit in which Alceste is embroiled; and finally, Alceste’s desire to have a private conversation with Célimène, with whom he is bizarrely and hopelessly in love. Alceste responds angrily both to Philinte’s advice and to its attendant suggestion of friendship, in a line that is repeated again and again in the film as Serge and Gauthier rehearse: “Moi, votre ami? Rayez cela de vos papiers.” This bilious volatility is perfectly mirrored in Serge’s own unpredictable attitudes: will he or won’t he finally agree to perform with Gauthier?

Le Guay has a lot of fun playing verbally and visually with the opposing attitudes of the two protagonists. Serge has a battered old Livre de poche edition of Le Misanthrope that looks like it was second-hand when he bought it in the sixties; Gauthier carries a shiny Larousse version. Gauthier wants to “sortir de l’élitisme crétin” and bring Molière to the public; Serge corrects his overly modern pronunciation (in the form of an alexandrine, no less): “Quand on joue les classiques, on respecte les vers.” (This does not go down well: “prépara-t-i-on, masturba-t-i-on,” spits Gauthier.) In both the play and the film, a common past binds the two protagonists together. There is a suggestion in Molière that Alceste and Philinte are like two brothers (“les deux frères de l’Ecole du mari”), with a reference to them both having been “sous mêmes soins nourris.” Gauthier recalls an episode early in his career when Serge took him to one side to “travailler le texte,” enabling him to conquer his stage fright for the first time. Molière reworks recognized classical authorities, Cicero’s De amicitia for example, on the shared experience required for true friendship; Philippe Le Guay writes a tetchy bromance. So far, so amusing. Watching two very fine actors perform lines from Le Misanthrope is hugely pleasurable, and I could well imagine discussing the interactions between Alceste and Philinte through the medium of a short clip of the film at this point.

Le Guay has a lot of fun playing verbally and visually with the opposing attitudes of the two protagonists. Serge has a battered old Livre de poche edition of Le Misanthrope that looks like it was second-hand when he bought it in the sixties; Gauthier carries a shiny Larousse version. Gauthier wants to “sortir de l’élitisme crétin” and bring Molière to the public; Serge corrects his overly modern pronunciation (in the form of an alexandrine, no less): “Quand on joue les classiques, on respecte les vers.” (This does not go down well: “prépara-t-i-on, masturba-t-i-on,” spits Gauthier.) In both the play and the film, a common past binds the two protagonists together. There is a suggestion in Molière that Alceste and Philinte are like two brothers (“les deux frères de l’Ecole du mari”), with a reference to them both having been “sous mêmes soins nourris.” Gauthier recalls an episode early in his career when Serge took him to one side to “travailler le texte,” enabling him to conquer his stage fright for the first time. Molière reworks recognized classical authorities, Cicero’s De amicitia for example, on the shared experience required for true friendship; Philippe Le Guay writes a tetchy bromance. So far, so amusing. Watching two very fine actors perform lines from Le Misanthrope is hugely pleasurable, and I could well imagine discussing the interactions between Alceste and Philinte through the medium of a short clip of the film at this point.

But there are one or two more serious points to be made, too. Is there a little bit of the eminently reasonable Philinte in Alceste? After all, Alceste’s response to an imperfect, self-obsessed world – to ignore its demands – seems perfectly rational. Is there a little bit of the arrogant Alceste in Philinte? He is certainly seeking to affirm his own authority, to change Alceste’s behaviour rather than accept it for what it is. As Serge and Gauthier swap roles, the film provides us with the perfect literalization of these questions. One could move onto a discussion of what the raisonneur figure does, exactly, in Molière. Is he himself the target of laughter? Is he a foil or a sounding board; an adversary or the perfect embodiment of “toute la sagesse humaniste?”[1] Michael Hawcroft has recently challenged and reassessed previous critics’ conclusions on the subject, arguing that the raisonneur has an advanced dramaturgical and comic structural function that allows him to alternate between all these different roles as the plot demands.[2]

All of the preceding points, though, relate to the first third of Alceste à bicyclette. After that, it loses its way. As impressive as Luchini and Wilson are, the supporting cast seems solely designed to add to the damp atmosphere of the Ile de Ré in winter. They are off-season anomalies, caught in a state of suspension while waiting for something better or something more. There’s the frustrated young waitress, Zoé, whose sole ambition is to star in porn films; the Italian divorcée, Francesca, attempting to sell her house; a bored real-estate agent; the silly, overly chatty proprietor of an empty hotel. In the course of the film, Zoé and Francesca interact with Serge and Gauthier in various increasingly uninteresting and clichéd ways. While there is some suggestion that we should think of these women in connection with Molière’s Célimène and Eliante, this idea never really goes anywhere. Nor do many of the film’s incoherent sub-plots, which include a fight with a taxi-driver and a cancelled vasectomy. One would not necessarily want to put one’s students through an analysis of these features. (If they did happen to have sat through the whole thing, one might nevertheless ask about the extent to which they thought that the bleak pessimism of the film’s ending is representative of Molière’s own dénouement.)

All of the preceding points, though, relate to the first third of Alceste à bicyclette. After that, it loses its way. As impressive as Luchini and Wilson are, the supporting cast seems solely designed to add to the damp atmosphere of the Ile de Ré in winter. They are off-season anomalies, caught in a state of suspension while waiting for something better or something more. There’s the frustrated young waitress, Zoé, whose sole ambition is to star in porn films; the Italian divorcée, Francesca, attempting to sell her house; a bored real-estate agent; the silly, overly chatty proprietor of an empty hotel. In the course of the film, Zoé and Francesca interact with Serge and Gauthier in various increasingly uninteresting and clichéd ways. While there is some suggestion that we should think of these women in connection with Molière’s Célimène and Eliante, this idea never really goes anywhere. Nor do many of the film’s incoherent sub-plots, which include a fight with a taxi-driver and a cancelled vasectomy. One would not necessarily want to put one’s students through an analysis of these features. (If they did happen to have sat through the whole thing, one might nevertheless ask about the extent to which they thought that the bleak pessimism of the film’s ending is representative of Molière’s own dénouement.)

In some ways, Philippe Le Guay has brilliantly spotted the filmic potential of Le Misanthrope. In others, he misses a few tricks. He could certainly have taken more from Molière’s dramaturgy: the seventeenth-century author’s insistence on Alceste’s and Philinte’s diverse interactions not just with each other, but with a full range of characters, all crucial to the advancement and conclusion of the plot. Still, as a starting point for discussion of honnêteté, of inauthenticity and the fickle norms of fashion and sociability, or of the function of the raisonneur figure, this film has classroom potential as a light-hearted, amusing opener to discussion.

Philippe Le Guay, Director, Alceste à bicyclette [Cycling with Molière], 2013, Color, 104 min, France, Les Films des Tournelles, Pathé, Appaloosa Développement, France 2 Cinéma.

- Georges Forestier, Molière en toutes lettres (Paris: Bordas, 1990), p. 148.

- Michael Hawcroft, Molière: Reasoning with Fools (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).