Mark S. Micale

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

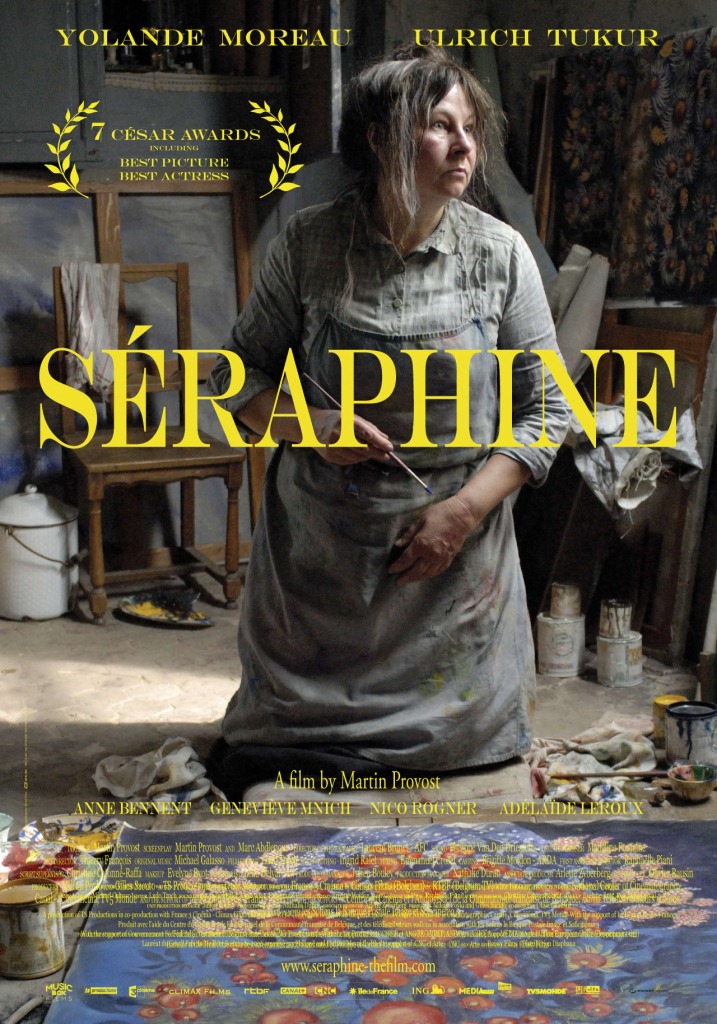

Films about “mad women artists” seem to be proliferating in France recently. Séraphine tells the story of Séraphine Louis (1864-1942?), played superbly by Yolande Moreau, a poor and simple domestique who began painting in middle age. Séraphine’s is a profoundly private, solitary world, and some visiting local nuns hint that she previously had problems with her mental health. Séraphine has no family, we learn, and her only daily conversations involve rote exchanges with the people she encounters as she goes about her work routines. She passes her days performing the same set of physically demanding chores whose repetitive nature comforts her.

In Séraphine’s adult life, nature, Catholic religion—especially the cult of the Virgin Mary—and painting are the great sources of solace and meaning. Mostly, she paints flowers, but interestingly the images emerge entirely from her mind rather than direct views of nature in the plein air Impressionist manner. Séraphine applies the paint with a brush and her fingers. When she can’t afford color paints, she grinds them herself from the physical world —from red wine, animal blood, flower juice, and church candle wax. She paints on small wooden panels, and the brilliant floral tones contrast markedly with her drab clothes and affectless life, as well as the picturesque stone buildings of the small village she inhabits. (The setting is intended to be Senlis, a tiny Picardie town, near Chantilly, about 40 miles north of Paris.) Eventually her art will be labelled “primitivist;” in her case, however, the source of inspiration is not the African savannah but the French rural countryside. For a sense of her style, think Van Gogh married with Grandma Moses.

In Séraphine’s adult life, nature, Catholic religion—especially the cult of the Virgin Mary—and painting are the great sources of solace and meaning. Mostly, she paints flowers, but interestingly the images emerge entirely from her mind rather than direct views of nature in the plein air Impressionist manner. Séraphine applies the paint with a brush and her fingers. When she can’t afford color paints, she grinds them herself from the physical world —from red wine, animal blood, flower juice, and church candle wax. She paints on small wooden panels, and the brilliant floral tones contrast markedly with her drab clothes and affectless life, as well as the picturesque stone buildings of the small village she inhabits. (The setting is intended to be Senlis, a tiny Picardie town, near Chantilly, about 40 miles north of Paris.) Eventually her art will be labelled “primitivist;” in her case, however, the source of inspiration is not the African savannah but the French rural countryside. For a sense of her style, think Van Gogh married with Grandma Moses.

Séraphine paints exclusively in her one-bedroom, top-floor apartment, late into the night, while she hums religious hymns and drinks her homemade “energy wine.” Her snobby local employers joke about her artistic efforts, which they reject as crudely unrealistic. (That is precisely what they are.) In 1912, however, the visiting German art dealer Wilhelm Uhde spies her paintings while she is working for him as a kitchen maid. (All the characters in the movie are given their real names.) An early champion of the painter Henri Rousseau (as well as an early buyer of Picasso and Braque canvases), Uhde immediately admires Séraphine’s work for its authenticity and expressive power.

The film tracks the story of Séraphine’s relationship with the avant-garde dealer as it develops over many years. Although he urged Séraphine to continue her painting, their budding friendship gets disrupted by the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, forcing Uhde to leave France in a hurry. Many years later–we eventually learn it is 1927–he returns to Senlis and seeks out Séraphine. Perhaps in part because of his encouragement, she has indeed continued to paint, but her canvases are now larger, somewhat more abstract, and much more self-confident artistically. Uhde begins to promote her paintings more systematically, bringing her some public recognition and sales. A small but select circle of avant-garde enthusiasts in Paris and Berlin agree with Udhe that Séraphine’s work is “alluringly naive,” suggesting that it deserves a place in visual modernism.

Twenty minutes before it ends, however, the film takes an unexpected turn. When the Great Depression hits France around 1930, both the sales of Séraphine’s paintings and the monthly stipend Uhde has been providing her evaporate. Having just begun to adjust to her new success, Séraphine doesn’t understand this change of fortune; she can’t cope and becomes oddly petulant. She seems to join those who are “ruined by success.” (For an analogy in our time, think Susan Boyle, the dowdy, small-town singer on the television show Britain’s Got Talent who in 2009 wowed audiences with her initial performance of the song “I Dreamed a Dream” but then collapsed after placing second in a later televised performance.) When Séraphine begins parading through town at dawn dressed in a bridal gown, the locals sympathetically notify the police–who respond by taking her away in a paddy wagon.

The film then shifts to the women’s asylum in Clermont, where Séraphine has been interned. Denied access to painting and the outdoors, she suffers bouts of confusion, crying, and anger. The one scene set in the asylum is reminiscent of the dungeon sequence from The Snake Pit (1955) in which the traumatized female protagonist wanders among demented geriatric patients who are much sicker than she. As the film ends, viewers are informed simply that Séraphine remained confined at the Clermont mental hospital until her death in 1942, although biographers are uncertain about when she died.

Séraphine is conceivably too long. The whining violin music that accompanies the main character’s scenes eventually grates. As I suggest above, the main character’s collapse seems too sudden psychologically, and her confinement for the remainder of her life never gets explained or explored. Although the film narrates their crossing paths, Director Provost chooses not to probe her relationship with Uhde, presenting it quite straightforwardly as that between an artist and critic. The one interpersonal dynamic is the contrast between the highly cultured Uhde and the entirely self-taught and unschooled Séraphine. Nonetheless, Provost does present Uhde’s emotional life as a kind of parallel phenomenon: the story of the German critic’s private life, first as a lonely and depressed gay man and then as the caretaker of his much younger and tubercular male lover/painter/protégé also contrasts with Séraphine’s romantically and sexually uneventful existence.

Moreau’s virtuoso performance, which earned her the Best Actress Prize of the National Society of Film Critics and the French César, easily sustains the film artistically. Historically-minded audiences are likely to enjoy the film because it complicates the standard narrative of artistic modernism on a number of levels. Séraphine is an avant-garde painter, yet her life and art are profoundly rural and religious rather than urban and secular. (At one point, Séraphine reports that she began painting after a personal directive from the Virgin Mary.) The one major male figure in the story is a supportive homosexual.

As an historian of psychiatry, I was left contemplating the real-life Séraphine’s fate. Throughout the film, Séraphine’s behavior was awkward, “different,” and somewhat anti-social, but never psychotic. She appears vacant emotionally, but she never harms herself or anyone else. Her mental decline comes off today as a circumstantial “nervous breakdown,” not overt insanity. Only when imprisoned psychiatrically, does she become agitated and fitful. A generation later in French medicine, such a patient would surely have been “decarcerated” back into the community.

Is Séraphine’s confinement the result of provincial ignorance, or society’s intolerance, or medical ineptitude? The film does not take a position or even formulate the question. In the short segment devoted to her institutionalization, Séraphine receives no treatment, no medicines, and not even a diagnosis; yet the film cannot be called “anti-psychiatric” per se. It remains unclear in fact if her tragic plight after 1933 is linked in any way with her identity as either an artist or a woman.

Scholars have now established unmistakably that European women of ability and creativity, ranging from the late medieval English mystic Margery of Kemp to Freud’s “hysterical” patients of the 1890s, were alternately misunderstood, pathologized, or suppressed by male medical elites and a patriarchal society. Just how Séraphine (and Séraphine Louis) relates to this tradition, however, is open to interpretation–which is probably another reason to watch and ponder the film.

The newest of the three films under review, Camille Claudel 1915 offers a very different sort of viewing experience. It relates the story of a recognized, Paris-based sculptor who at mid-life was imprisoned in an asylum in southern France by her disapproving family after a severe crisis in her personal life, namely the end of her tempestuous grande passion with mentor Auguste Rodin. In contrast to the biopic approach of the other two films, Camille Claudel 1915 takes place entirely during the winter of 1915. The lead role is played by the internationally acclaimed actress Juliette Binoche, and the film directed by award-winner Bruno Dumont.

Also unlike Séraphine, Camille Claudel 1915 takes place almost entirely inside a “madhouse,” and like The Snake Pit or One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), it is a study of the daily institutional life of patients and staff. The facility in question, however, is Catholic: there is no medical regimen, nuns serve as nurses, and Camille receives no treatment of any sort, and certainly not the psychotherapy that we sense would benefit her greatly. Although we continually see how fragile and depressed she is, Camille is never diagnosed. In his one encounter with her, the senior male physician at the asylum listens to her with little interest before observing laconically that Camille is still obsessed by Rodin and the belief that her famous ex-lover stole her work.

Also unlike Séraphine, Camille Claudel 1915 takes place almost entirely inside a “madhouse,” and like The Snake Pit or One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), it is a study of the daily institutional life of patients and staff. The facility in question, however, is Catholic: there is no medical regimen, nuns serve as nurses, and Camille receives no treatment of any sort, and certainly not the psychotherapy that we sense would benefit her greatly. Although we continually see how fragile and depressed she is, Camille is never diagnosed. In his one encounter with her, the senior male physician at the asylum listens to her with little interest before observing laconically that Camille is still obsessed by Rodin and the belief that her famous ex-lover stole her work.

The physical setting of the scenes mirrors Claudel’s bleak state of mind: room interiors are sparsely furnished and painted in neutral colors, the asylum is built of gray stone, and the courtyards feature dead, gnarly trees. Patients are clad mostly in black, and the surrounding wintertime countryside is rocky, colorless, and uninhabited. Most deadening is Claudel’s daily routine: there are no sculpting materials, books, or newspapers at the asylum. Viewers, in fact, never glimpse the sizable body of sculpture that Claudel had produced earlier in her life.

In Dumont’s film, the patient-protagonist seems less sick than the other female inmates around her: they are deranged, demented, or mentally deficient whereas Claudel is desperately sad but not “out of her mind.” Poignantly, in several scenes she assists the other patients who are in greater need. Dumont’s film was controversial in France because in several scenes he used real-life psychiatric patients, adding to the film’s impact.

Not Camille Claudel (1864-1943) but Juliette Binoche seems to be the true subject of the film. Binoche inhabits her character brilliantly. Deathly pale, her face in close up becomes a canvas for an extraordinarily subtle variety of emotions. Without make up and with signs of frequent crying, her facial beauty nonetheless remains irrepressible. Binoche’s transitions from one affect to another are particularly masterly. The film could easily double as a case study–at once scientific and aesthetic—in human facial physiognomy.

In Camille’s monotonous daily life, her brother Paul comes to visit one day. This encounter provides the main “action” of the film’s second half. Paul Claudel is a well-known poet working in the French Symbolist style, who is usually classed with Verlaine, Rimbaud, and Valéry. Unlike his sculptor sister, he inherited his mother’s strict Catholic piety, and by the wartime period depicted in the film was deeply, even morbidly, religious.

Paul Claudel, played by Jean-Luc Vincent, comes across as a bland, emotionless character with all the charisma of a Victorian undertaker. We first encounter him on a country road, praying out loud on his hands and knees, on his way to the asylum. In his daily diary, Paul addressed God directly, and in one scene, he seems to despise his own corporeality, with hints at self-flagellation. It was Paul and his mother who originally had Camille committed. Earlier in her life, they had been bitterly opposed to Camille’s pursuit of a career in the arts and condemned her relationship with Rodin. Paul, we learn, believes that art and adultery drove Camille insane. He prays that her inner demons might be exorcised, which is no metaphor for her psychological suffering. He views emotions as a terrible curse and has done his best to purge his own from consciousness. He brings his suffering sister no gifts or even greetings, manifesting the family’s dysfunctionality, a likely precondition for Camille’s deterioration. Even before he reaches the hospital, it is clear that Paul will not be able to help his anguished sister, demonstrating instead that he is part of the problem.

Although excited by his visit, Camille’s conversation with her brother is intensely fraught. Both Paul and Camille, we see, are trapped inside their closed mental worlds where they are doomed to remain. Which worldview is more troubled, more deluded, is open to debate. The film ends bleakly with Paul’s departure and no opportunity for the release of Camille, who, shockingly, remained imprisoned until her death in 1943, the entire second half of her life.

An example of “slow cinema” with longish, dialogue-free stretches, Camille Claudel 1915 is probably too painful existentially for use in the college classroom. (Imagine The Snake Pit or Girl Interrupted directed by Ingmar Bergman, and you get a good sense of the film’s atmosphere.) Although French history viewers might be familiar with the Claudel/Rodin saga, which was so well depicted in the earlier biopic Camille Claudel (1988)–directed by Bruno Nuytten with Isabelle Adjani as Camille and Gérard Depardieu as Rodin–non-movie-buffs will likely require some biographical information to understand the second film, where it is not included.

Besides Binoche’s breathtaking performance, the most memorable aspect of the film is its short temporal frame. Dumont gives us an intensive Solzhenitsyn-like reconstruction of several days in Camille’s incarcerated existence as she suffers and survives–One Day in the Life of the Psychiatric Patient Camille Claudel. The problem is that both the film and the biographies about her life suggest that Camille Claudel did not need to be incarcerated at all. Like Séraphine, Camille never hurt herself or anyone else, and she was fully in touch with “reality.” She was a proven highly talented artist who at one point in her life, in response to a specific amorous relationship, had several temper tantrums and destroyed some of her artwork. How many male artists throughout history responded with similar outbursts? Historically, a passionate male artist seems to be interpreted as a temperamental genius; a female artist of “excessive passions” is classified as a mental patient to be secluded and silenced. That is one lesson from this powerful, starkly beautiful film.

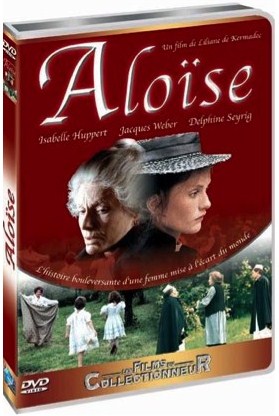

The only film among the three to be directed by a woman, Liliane de Kermadec’s Aloïse came out in 1975 and a DVD version was reissued in 2008. Born in Lausanne, Switzerland, Aloïse Corbaz (1886-1964) aspired to become an opera singer and had enough talent to make this plausible, yet her conservative family sent her to Germany to work as a governess at Kaiser Wilhelm II ‘s court in Potsdam, just before the outbreak of the First World War. Romantically inexperienced, Aloïse developed an obsessive crush on the emperor himself. After her dismissal from her post, she returned to Switzerland, racked by guilt and loneliness, and began to exhibit ranting, delusional behavior. In 1918, at the age of 32, she was forcibly confined at the Cery Psychiatric Clinic outside Lausanne, where she was diagnosed with “schizophrenia,” a brand new clinical label formulated by the Zurich psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler. She spent the rest of her life, or a total of 46 years, at the hospital.

The only film among the three to be directed by a woman, Liliane de Kermadec’s Aloïse came out in 1975 and a DVD version was reissued in 2008. Born in Lausanne, Switzerland, Aloïse Corbaz (1886-1964) aspired to become an opera singer and had enough talent to make this plausible, yet her conservative family sent her to Germany to work as a governess at Kaiser Wilhelm II ‘s court in Potsdam, just before the outbreak of the First World War. Romantically inexperienced, Aloïse developed an obsessive crush on the emperor himself. After her dismissal from her post, she returned to Switzerland, racked by guilt and loneliness, and began to exhibit ranting, delusional behavior. In 1918, at the age of 32, she was forcibly confined at the Cery Psychiatric Clinic outside Lausanne, where she was diagnosed with “schizophrenia,” a brand new clinical label formulated by the Zurich psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler. She spent the rest of her life, or a total of 46 years, at the hospital.

Soon after her institutionalization, however, Aloïse began to paint and draw. Unlike Séraphine and Camille, Aloïse’s medical handlers—specifically the male hospital director and a female staff psychiatrist—provided her with the space and materials to pursue her artistic impulses. By the 1950s, she had produced over 800 drawings, some of them quite large. Aloïse drew with colored pencils and crayons, overlaid at times with watercolor. Her favorite subject matter was either natural/floral or romantic/erotic, featuring young, curvateous women with male partners in military uniform. She filled every inch with swirling decorative lines and symbols, with a preference for brilliant Fauve colors.

Around 1947, Aloïse’s asylum art was “discovered” by the French painter, sculptor, and art theorist Jean Dubuffet, who was entranced by its unique, uninhibited expressivity. Dubuffet visited Aloïse regularly for the next twenty years. He gave lectures about her artwork and arranged a local exhibition to showcase it. For Dubuffet she typified “l’art brut—raw or rough art”—or image-making created outside traditional art establishments. By the time of her death in the mid-1960s, Aloïse had become a recognized artist in Switzerland, France, and Japan, and in 2012, the Fine Arts Museum of Lausanne mounted a major retrospective of her oeuvre, accompanied by a full catalogue raisonné.

Aloïse’s story is absorbing, but the poor, grainy DVD transfer (2008) does it a disservice. (Serious students of the artist should also search out the 1963 documentary Aloïse’s Magic Mirror, which features interviews with the elderly artist.) Since the film’s narrative follows the artist from her adolescence to her death, the role of Aloïse is played by four different actresses, including a young Isabelle Huppert. The film highlights how Aloïse’s entourage failed to appreciate her talents: her family was affectionate but unwilling to send the young woman to a Conservatory for proper musical training. The local Calvinist minister advised her to use her vocal gifts to glorify God, not to pursue a career. And the cold, highly regulated court of the Kaiser had little interest in anything outside service to the Fatherland. At each key moment in her young life, some stern or unsupportive patriarch blocked her self-expression.Trapped by her petit-bourgeois milieu, she has no one to turn to about her internal turmoil once she finally develops strong emotional and erotic feelings for another person.

Aloïse was born and died twenty years after Séraphine and Camille, and she was treated in an urban clinic associated with a leading hospital in Switzerland, not at a small asylum in some isolated setting. These differences matter. The Cery Clinic, where the second half of the film transpires, is no psychiatric gulag. The same society that had earlier oppressed Aloïse manages to foster, recognize, and finally publicize her artistic accomplishments. What viewers may not know is that Aloïse’s internment corresponds with “the golden age of Swiss psychiatry” when an array of new, progressive ideas about psychodynamic psychotherapy were developed in major Swiss clinics. It was, of course, the age of Jung and Piaget but also of Binswanger, Bleuler, Claparède, Flournoy, Forel, Klages, Pfister, and Rorschach, and a prime site for the dissemination of existential analysis and phenomenological psychiatry. Liliane de Kermadec does indeed depict clinic director Hans Steck and internist Jacqueline Porret-Forel as heroic figures.

Viewing these films together highlights intriguing similarities and differences. Most obviously, all three films deal with women artists who lived in Francophone cultures during the first half of the twentieth century, and whose personal and artistic lives were affected by mental breakdown and, as a consequence, long-term institutionalization. As readers may have noticed, Séraphine and Camille were born in 1864 and died only one year apart. All three were eventually recognized and won their place within “the history of art.” Each formed ties with a more established figure in the art world–Rodin, Uhde, Dubuffet– who enabled their public recognition. Moreover, their work is still being evaluated and interpreted today. A last common feature: it is highly unlikely that any of these women would today be institutionalized for life.

The differences in the life stories, as presented in the films, are still more instructive. Art, gender, modernity, and mental health intersect in substantially different ways here. Religion is indispensable for Séraphine but a source of oppression for Camille and Aloïse. While Séraphine and Camille were reduced to silence, Aloïse created all of her pictures at the clinic. While mental illness ended the first two careers, Aloïse became an example of “the art of the insane,” where patients channel psychopathology into cultural creativity. Her achievements raise the oft-posed question about the relations between madness and modern art, schizophrenia and creativity. Only Camille had formal training. Of the three, only Aloïse produced art that is arguably gendered, with its overt reference to sex and her coded use of blues and pinks. Likewise, only de Kermadec’s film could be called feminist, displaying explicit sexual politics. Even the “psychopathological styles” of the three artists differ: whereas Séraphine and Camille Claudel were cocooned in the intensely private mental world we call melancholy, Aloïse is more extraverted and “maniacal.”

Is there something inherently “French” about the mad female artist? I don’t think so; I wager, rather, that the simultaneous appearance (or re-appearance) of the films in this review reflects the longstanding interest in the visual arts of the Francophone world, as well as, of course, the rise of feminist biography, academic gender studies, and feminist art criticism. Still, the contrast between these three “mad” artists, and the trajectories, say, of the “female Impressionists” Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, the German graphic artist Käthe Kollwitz, and the British modernist sculptor Barbara Hepworth invites further analysis.Viewed together, the films raise the possibility of a comparative and comprehensive study of women, art, and psychology in both the past and the present. Such a study would be timely and most welcome.

Martin Provost, Director, Séraphine, Color, 2008, 125 min., Color, France, Belgium, TS Productions, France 3 Cinéma, Climax Films

Bruno Dumont, Director, Camille Claudel, 1915, Color, 2013, 93 min., France, 3B Productions, arte France Cinéma, C.R.R.A.V Nord-Pas de Calais

Liliane de Kekrmadec, Aloise, Color, 1975. 115 min., France, Unités Trois