Clare Crowston

University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

Among the more than 250,000 visitors who descend the spiral staircase to the Parisian catacombs each year, who does not at some point in the ensuing spectacle ask him or herself: how did they do this? Andrew Miller’s Pure provides a satisfyingly grim and detailed response. The year is 1785, and like another ambitious and idealistic young provincial engineer, Baron Ponceludon de Malavoy of the film Ridicule, Jean-Baptiste Baratte appears at Versailles seeking to make his mark on the world. Whereas the noble Ponceludon has the social credentials to stake his claims in the salons and ballrooms of court society, Baratte (eldest son of a Norman master glove maker and favored client of the local count) receives a curt audience with “the minister” and then escapes the palace’s labyrinthine corridors for Paris. Ponceludon dreams of draining the malarial swamps of the Dombes, Baratte receives an even more daunting – and disgusting – task that of emptying the reeking Saints-Innocents Cemetery.

Having served as burial grounds for centuries of Parisians, through plagues, famines and the ordinary toll of death, the cemetery is literally bursting at its seams. Over the years, skeletons exhumed from common pits have been stacked in charnels, so that the pits could be filled once more. The closing of the church and its cemetery in 1780 finally halted the burials but did nothing to remove the source of its pollution. The great hoard of decomposing bodies continues to poison the air and the water supply, a danger horrifically demonstrated by the collapse of a wall separating a mass grave from a private home. In an age of enlightened notions of public hygiene and mounting public opinion, the royal government has decreed that something must be done.

Having served as burial grounds for centuries of Parisians, through plagues, famines and the ordinary toll of death, the cemetery is literally bursting at its seams. Over the years, skeletons exhumed from common pits have been stacked in charnels, so that the pits could be filled once more. The closing of the church and its cemetery in 1780 finally halted the burials but did nothing to remove the source of its pollution. The great hoard of decomposing bodies continues to poison the air and the water supply, a danger horrifically demonstrated by the collapse of a wall separating a mass grave from a private home. In an age of enlightened notions of public hygiene and mounting public opinion, the royal government has decreed that something must be done.

Miller erects his novel on the real-life historical scaffolding of the disinterment of the cemetery’s dead and their transfer to a subterranean quarry on the southern borders of the city. After two miserable years at the mines of Valenciennes, Jean-Baptiste Baratte is both tempted by the promise of royal gratitude for this service and overwhelmed by the enormity of the task assigned to him. He enlists the assistance of Lecoeur, a mine manager at Valenciennes, who has languished in the isolation and brutality of the mines, cherishing memories of the brief friendship that flourished between the two young men and the utopian schemes they hatched in the long winter nights. Lecoeur arrives with a small army of miners, skilled and hardened Flemish laborers who will remain a mysterious tribe unto themselves, camped in tents in the churchyard, with their own language and rituals and, ultimately, loyal only to their own unspoken leader.

Despite his inner doubts and uncertainties, Baratte’s superior status as an engineer trained at the Ecole royale des ponts et chaussées earns him lodging in the nearby household of a master cutler. Baratte’s arrival disrupts the fragile stability of the family – whose breath reeks of the poisoned atmosphere they inhabit – unleashing emotional turmoil that will ultimately explode into violence. As the workers take up their grisly task, Baratte becomes enmeshed in the tensions coursing through the streets beyond the cemetery walls. Armand, the organist of the moldering church, one of the rare foundlings to survive the Hôpital des enfants trouvés, has introduced him to a sect of “men of the future,” whose nocturnal graffiti hurl dire threats and denunciations at the regime. Baratte also encounters a prostitute, nicknamed the “Austrian” after the blonde hair and widely-rumored promiscuity of the Queen, who entrances the otherwise virtuous engineer. The doctor Guillotin, one of several medical men keen to observe the process of disinterment, provides a sympathetic note of kindly, enlightened wisdom. After months of grueling labor, a series of additional unexpected acts of violence and their consequences mark the fiery culmination of the plot; in the aftermath the protagonists quietly disperse to the futures awaiting them. The book closes with Baratte’s return to Versailles to report on the completion of the project, whereupon he stumbles on the death throes of the Siamese elephant, whose captivity in the Versailles gardens was one of the few pieces of information conveyed to him by the minister during his first visit.

Pure, winner of the 2011 Costa Best Novel Award, was greeted with critical acclaim in the author’s native Britain and the United States. As previous reviewers have noted, the ambience Miller crafts is chillingly gloomy and evocative. Anyone familiar with the cold damp reek of Parisian streets on a dark winter afternoon will immediately feel at home in this novel. The reader is fascinated by the enormity of the labor involved in emptying the cemetery, by the technical and physical demands it presented, and by the impact such an act would have had on the workers involved, their supervisors and the surrounding neighborhood. Miller’s brilliantly worded account of this labor convinces the reader and draws us into the grisly details he unfolds. His story, on one level, is a quiet yet forceful tribute to the heroism of the workers responsible for the massive public works projects that made the modern city.

The cast of characters is sympathetic if somewhat predictable – the self-doubting striver from the provinces (who puts himself to sleep at night with a few pages of Buffon and a ritual incantation of his belief in reason), the stone-eyed representative of the forces of order, the libertine musician, the maid of loose morals, the mad priest, and even the hooker with a heart of gold. Their familiarity is perhaps intentional, all the better to establish the allegory at the novel’s heart. Miller sets these stock figures at play in a satisfyingly complex and ambiguous manner. The momentum of the plot continually pulls us forward, at least until the dramatic denouement, after which the author himself seems to lose interest somewhat in the Herculean tasks at which he has set his protagonists.

Readers of this review may be interested in more specific questions about the historical accuracy of the novel and its potential use in the classroom. To the question, does Miller succeed in creating a fully realized late eighteenth-century world? I would answer, on the whole, yes, especially the material world of humble and middling households and the grinding toil of physical labor. He convincingly conveys the fine texture of daily life: the cascade of petticoats, ribbons, bonnets, and other bits of finery accumulated by the daughter of a successful master craftsman; the social and intellectual pretensions represented by the pistachio-green suit and Voltaire’s “banyan” that Baratte drunkenly acquires; the pig trotters, pipes, and copious brandy provided to keep up the miners’ morale and the celebratory roast chicken and oysters consumed at a performance of the Mariage de Figaro. In the omnipresent piles of human and animal excrement, the guttering candles, the bitter cold of unheated rooms, the recourse to bleeding as treatment for a head wound, the chapped hands of laundresses scrubbing in cold water, and in the welcome warmth of a steamy café, we feel the heavy weight of the body and its needs in the pre-modern age. Miller’s novel presents the reader both with the achievements of the eighteenth-century consumer revolution (coffee, brightly colored clothing, street lighting, newspapers, and theater) and the ongoing precariousness of life; we witness the Rabelaisian vitality of the bustling city and the ubiquity of suffering and death.

His deficiencies in historical awareness, however, are also in evidence, sometimes wincingly so, for example, in his characters’ repeated references to hectares, meters and other units of the metric system that was itself a product of the French Revolution. (The hero’s profession as an engineer who is constantly pulling out his ruler to measure something produces distressingly frequent instances of this gaffe). From a historian’s point of view, I was less troubled by the occasional off notes than by one aspect of the novel highly praised by critics: the function of the story as an allegory for the approaching Revolution, whose footsteps –like the undead lurking in so many fictional churchyards– can be heard treading ever closer, ever more quickly. The organist’s “party of the future” evokes, and may implicitly refer to, Robert Darnton’s hacks, who attacked the monarchical regime in increasingly strident and vicious terms in this period. Beyond bringing to life the low-life of the Enlightenment, the author goes one better than François Furet: the logic of the Terror does not have to await 1789, but is already present in 1785. Armand advises Baratte that he suffers from the politics of undrawn conclusions, that he does not have much time left to make his choice between the doomed past and the looming future, and that “ownership will soon be a much more flexible concept.”

Miller is nothing if not clear in his purposes. We need no help recognizing the destruction and purification of the hulking church and the removal of its dead as a metaphor for the painful but necessary destruction of a decrepit and ossified regime. The elephant in the room is, in this case, a literal breathing and dying creature. In case we somehow still miss the point, Doctor Guillotin is always on hand to remind us in which direction we are headed. And the mysterious, unknowable crowd of workers, following its obscure loyalties and motivations is, we learn, already well versed in the art of burning buildings. At stake in Baratte’s tortuous endeavors, we are to understand, is nothing less than the fate of the nation itself and the ambivalent modernity toward which it is hurtling.

All this makes, as the glowing reviews testify, for an exciting and dramatic narrative. It does not make for good history. I would not assign this book to students – and it must be said that there is no evidence Miller had any intention of seeing his book enter the history classroom – because his Revolution, the Revolution of 1793, is a foregone conclusion. Having tried so hard to keep alive in students’ minds the fact that no one knew on July 13, 1789 what would happen on July 14 (let alone on August 4, 1789; September 2-6, 1792; or January 21,1793), I would not encourage the belief that a nebulous conspiracy existed within the common people of Paris from 1785 to bring down the monarchy through violence and create a wholly new regime, with common ownership of property. To do so would be to forgo entirely the ways in which the events of the Revolution themselves changed peoples’ ideas, opened up new political possibilities, sundered groups apart, forged new alliances and made the formerly unimaginable into the urgently necessary. In short, the Revolution as process, not plot.

Miller’s anachronistic use of the metric system, it seems, is not merely a mistake in historical detail. It is the telling sign of a text that could only have been written from the perspective of a Revolution that has already happened. In that sense, the author ultimately fails to enter fully the mindset of 1785, whose daily chores of dressing and undressing, eating and excreting, toiling and promenading, he otherwise captures so well.

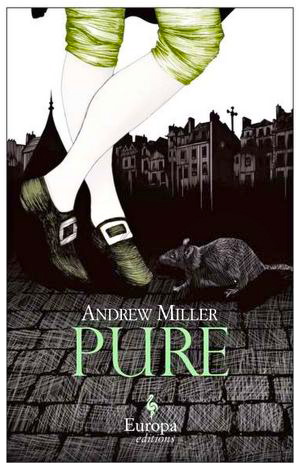

Andrew Miller, Pure (New York: Europea Editions, 2011)