Jay Winter

Yale University

The Grand Illusion is the finest film made about the Great War, perhaps the finest film made about war tout court. I am far from alone in this judgment. Like other works of genius, Renoir’s 1937 film is too quicksilver, too intelligent, to be placed in any one category, even a superlative one. It is a work of art which defies simple description and conventional analysis.

What helps gives this film its extraordinary power? There are many answers to this question. We can point to a cast of exceptionally gifted actors at the height of their powers, to the pacing and rhythms with which Renoir propels his prisoners of war – and all those in the film are prisoners of war — to their fates, to the delicate handling of a love story which, in other hands, would have turned mawkishly sentimental. We can point to the inspired choice of settings of the final part of the story in Haute Koenigsberg in Alsace, transformed into somewhere in the east of Germany, and the final denouement in the snow of the German-Swiss border. Both provide locations as remote as possible from Verdun and the Somme, once more distancing us from a conventional war film and enabling us to see war by not seeing it, and thereby to travel in our minds to violent moments and places which film can never capture.

Here is the beginning of an answer to the question as to why the Grand Illusion has such magical power. It is the enduring, indeed the classic cinematic statement of indirection, of disclosing war by not showing it.

Let me make a small diversion into the history of cinema to develop this argument. War films have a history that may be divided into three parts: the first is the era of silent films and of those filmmakers who made talkies but who carried on the earlier traditions of silent films. This was an era of inevitable indirection, of suggestion and gesture, rather than big picture pseudo-realism. What a contrast when from roughly 1940-1970 came the era of the spectacular in war films, in which special effects and scale forced viewers to see the epic character of war. In my view, these epics failed to show war by pretending that they could. Then came a third period, displaying more moral and visual ambiguity. With the Vietnam War debacle, showing war as grandiose spectacle came to take a back seat to showing its destructive effects on soldiers, victorious and vanquished alike, even if they survived combat. Films of indirection returned, drawing their inspiration from the locus classicus of the genre: Renoir’s Grand Illusion. That is what makes his film, now nearly 75 years old, look and feel so modern. It is the antithesis of Hollywood and all the cheap clichés it has peddled about war in the genre’s heyday, from the 1940s to the 1970s, and still occasionally later.

Let me make a small diversion into the history of cinema to develop this argument. War films have a history that may be divided into three parts: the first is the era of silent films and of those filmmakers who made talkies but who carried on the earlier traditions of silent films. This was an era of inevitable indirection, of suggestion and gesture, rather than big picture pseudo-realism. What a contrast when from roughly 1940-1970 came the era of the spectacular in war films, in which special effects and scale forced viewers to see the epic character of war. In my view, these epics failed to show war by pretending that they could. Then came a third period, displaying more moral and visual ambiguity. With the Vietnam War debacle, showing war as grandiose spectacle came to take a back seat to showing its destructive effects on soldiers, victorious and vanquished alike, even if they survived combat. Films of indirection returned, drawing their inspiration from the locus classicus of the genre: Renoir’s Grand Illusion. That is what makes his film, now nearly 75 years old, look and feel so modern. It is the antithesis of Hollywood and all the cheap clichés it has peddled about war in the genre’s heyday, from the 1940s to the 1970s, and still occasionally later.

In each of these approaches to filming war, I believe directors have opted for one of two registers, or combinations thereof– the spectacle or indirection. The Grand Illusion was a liminal film, bordering on the silent era, when the world of cinematic extravaganza remained a relatively rare phenomenon, with notable exceptions from Gance to Eisenstein. In 1937 war appeared increasingly inevitable, but the soldiers in Renoir’s film were not those of the Second World War. They were men of a gentler age.

The Second World War offered directors the liberty to latch cinema’s power to simplify and dramatize to a cause that was clearly intelligible as a conflict between good and evil. Post-1970 war films adhered to this “good war” version –oscillating between moral simplification and depiction of the horrors and moral ambiguities of war itself–affecting how the public has come to view war in the last few decades.

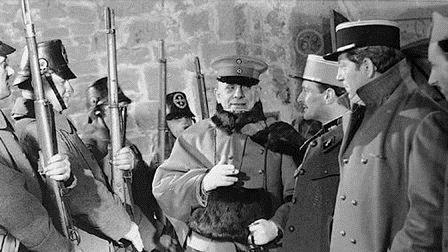

With this in mind, let us return to the Grand Illusion. Neither a pacifist nor a patriotic film, it is one of the earliest instances of depicting war as morally ambiguous. All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) was a pacifist film, with German soldiers played with conspicuous American accents, and Renoir avoids such heavy-handedness. He doesn’t lecture us; he ministers. This universal gentleness is what struck viewers with such force when the Grand Illusion was released during the Paris world’s fair of 1937. German soldiers and French soldiers are ordinary people wearing uniforms. There is virtually nothing to distinguish between them, their hopes, their frustrations, their sadness. Renoir’s plot is predicated on human solidarity, demonstrated in the fraternity among prisoners-of-war of various nationalities and their guards; in the code of honour shared by officers in opposing camps.

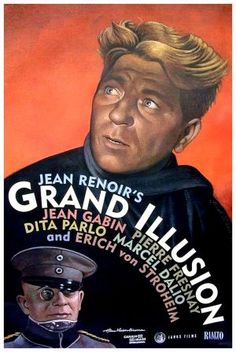

The movie opens with the arrival of a fresh crop of French prisoners-of-war, shot down by a German ace, von Rauffenstein, played by Erich von Stroheim, and focuses on three who happen to share a cell. They are Maréchal, a worker from Lyon played by Jean Gabin; de Boieldieu, a professional soldier played by Pierre Fresnay, and Lieutenant Rosenthal, a Rothschild-style wealthy Jewish Frenchman played by Marcel Dalio. We meet them again in a second prisoner-of-war camp set in a medieval castle, commanded by none other than Rauffenstein, whose injuries ended his carrier as pilot and turned him into a policeman, the only way, he explains, that he can still pretend to serve his country. His castle, he reminds his prisoners, is one from which escape is impossible. The latter parts of the film depict Maréchal and Rosenthal’s escape, enabled by the diversionary bravery of de Boieldieu, a geste that costs him his life.

Throughout the film, Renoir depicts small incidents that undercut the hostility between the two sides, each composed of men who are trapped in a seemingly endless conflict. In one early scene, a German airman cuts the meat of a recently captured French pilot at a lunch where all sit as equals. Indeed, the German commander himself bows his head in respect and apologizes to his French guests when a German soldier walks in, holding a wreath for the Frenchman’s dead comrade. Later in the film, Jean Gabin screams out in his solitary confinement that he just wants to hear someone speaking French. His gaoler, a mustachioed old codger, can’t give him what he wants, but offers the next best thing – a harmonica. Hearing the prisoner practice, the gaoler explains to a fellow German soldier the Frenchman’s frustration, reflecting what they all knew: that the war had lasted much too long.

Throughout the film, Renoir depicts small incidents that undercut the hostility between the two sides, each composed of men who are trapped in a seemingly endless conflict. In one early scene, a German airman cuts the meat of a recently captured French pilot at a lunch where all sit as equals. Indeed, the German commander himself bows his head in respect and apologizes to his French guests when a German soldier walks in, holding a wreath for the Frenchman’s dead comrade. Later in the film, Jean Gabin screams out in his solitary confinement that he just wants to hear someone speaking French. His gaoler, a mustachioed old codger, can’t give him what he wants, but offers the next best thing – a harmonica. Hearing the prisoner practice, the gaoler explains to a fellow German soldier the Frenchman’s frustration, reflecting what they all knew: that the war had lasted much too long.

The French prisoners’ pride and their singing of the Marseillaise at the recapture of Fort Douaumont in June 1916 (in the midst of the battle of Verdun) might suggest Renoir’s taking sides. However, the tenderness shown by a German woman to Gabin and Dalio after their escape undercuts such a reading. Dita Parlo, playing the German war widow, describes the men in her family to her “guests” not by name but by the battles in which they were killed. She looks annoyed when she catches Jean Gabin looking at her longingly as she is washing the floor, but then keeps her door slightly ajar after they celebrate a highly unusual Christmas to the joy of Ilse’s daughter Lotte. And once Gabin and Parlo become lovers, who is to say that the key to the mysterious title of the film is not in Gabin’s promise to return to Parlo once the war is over?

The French prisoners’ pride and their singing of the Marseillaise at the recapture of Fort Douaumont in June 1916 (in the midst of the battle of Verdun) might suggest Renoir’s taking sides. However, the tenderness shown by a German woman to Gabin and Dalio after their escape undercuts such a reading. Dita Parlo, playing the German war widow, describes the men in her family to her “guests” not by name but by the battles in which they were killed. She looks annoyed when she catches Jean Gabin looking at her longingly as she is washing the floor, but then keeps her door slightly ajar after they celebrate a highly unusual Christmas to the joy of Ilse’s daughter Lotte. And once Gabin and Parlo become lovers, who is to say that the key to the mysterious title of the film is not in Gabin’s promise to return to Parlo once the war is over?

That title has driven commentators to distraction for 75 years, and will continue to do so. What a brilliant and tantalizing bit of indirection. I have no idea what the title means, and revel in that uncertainty. Was the “grand illusion” a reference to Norman Angell’s Great Illusion of 1910, which argued that war never paid? Was it a poetic way of capturing the wonderful conversation between the gallant officer de Boieldieu and von Rauffenstein (memorably sporting a neck-brace and monocle), who both agree that the aristocratic order they inhabit will be gone after the war? Perhaps the world has no more need of us, says Boieldieu, and don’t you find that is a pity? responds Rauffenstein. Perhaps, says his prisoner, a man whom he will kill as the Frenchman teases his men across the fortress walls with his man-made flute –Boieldieu, after all, is the fife-playing god of the forest—long enough to distract the German detachment to allow Maréchal and Rosenthal to make good their escape. Perhaps indeed.

All of the film’s delicious ambiguities nod toward the elegiac character of the film. There are plenty of laughs for those who know the absurdities of war. Franco-British relations are reduced to a dialogue of the deaf, as a French prisoner tries to tell a tennis-racket-carrying British newcomer to the prison camp about the escape tunnel they have dug. The Brit simply can’t understand French. Russian prisoners feed a fire with the books the Czarina has sent for moral uplift to men who yearn not for Dostoyevsky but for drink. His fellow inmates mock the French schoolteacher who decides to translate Pindar without a hope of understanding him. “Poor Pindar” observes the camp commandant, at the man’s foolish dream. And what of the commandant’s own foolish dream: that he can continue to serve his country no longer as a combatant but as prison commander despite viewing it as a meaningless existence? Yes, war is meaningless, and yet here it is engulfing them all.

All of the film’s delicious ambiguities nod toward the elegiac character of the film. There are plenty of laughs for those who know the absurdities of war. Franco-British relations are reduced to a dialogue of the deaf, as a French prisoner tries to tell a tennis-racket-carrying British newcomer to the prison camp about the escape tunnel they have dug. The Brit simply can’t understand French. Russian prisoners feed a fire with the books the Czarina has sent for moral uplift to men who yearn not for Dostoyevsky but for drink. His fellow inmates mock the French schoolteacher who decides to translate Pindar without a hope of understanding him. “Poor Pindar” observes the camp commandant, at the man’s foolish dream. And what of the commandant’s own foolish dream: that he can continue to serve his country no longer as a combatant but as prison commander despite viewing it as a meaningless existence? Yes, war is meaningless, and yet here it is engulfing them all.

The unsaid is the motor of so much in this film: Renoir lingers on the faces of German children (new recruits with boyish faces) playing at being soldiers while older French soldiers in confinement play at children’s games. This Includes the lark of driving their enlisted German guards around the bend, by piping away after being ordered to cease and desist; they do so for a bit, that is, until Pan himself, Boieldieu, persists, giving up his life to ensure Gabin and Dalio’s getaway.

My claim is that the Grand Illusion said more about war than any other film precisely because of its relentless indirection: it shows nothing of combat itself, thereby mocking the pretentions of film directors who aimed to capture war by showing the stupendous force of artillery barrages or the breathtaking sight of soldiers going over the top to face murderous machine gun fire, or the dizzying acrobatics of air warfare. Jean Renoir made the spectacular approach to war films look ridiculous. Instead, he captured its inner essence by leaving its outer manifestations to the imagination. Suggested fears or horrors seem almost always worse than fears or horrors spoon-fed to an audience. In this unique film, Renoir made us know war, feel war viscerally, pity those trapped in it, more fully and more movingly, than any other artist. The Grand Illusion is more than a classic. It is a masterpiece.

Jean Renoir, Director, La grande illusion [Grand Illusion], 1937, 114 min., Black and White, France, Réalisation d’art cinématographique (RAC), Janus Films (USA), The Criterion Collection DVD (2004.2008)