Don Reid

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

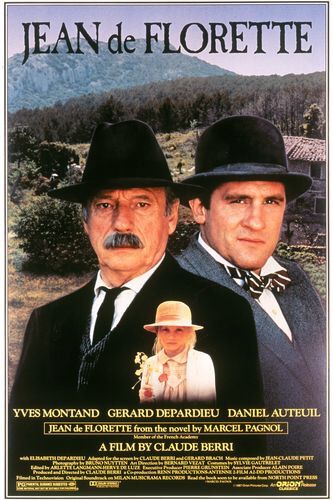

The great change brought by the trentes glorieuses was the transformation of France from a nation with a large population of paysans to one with a much smaller number of agriculteurs. Marcel Pagnol’s 1963 novels, Jean de Florette and Manon des Sources [Manon of the Spring] (the latter based on a screenplay and film done by Pagnol in 1952) and Claude Berri’s films of these works (1986) offered a representation of the prewar paysan in Provence that appealed to urbanizing French men and women who spoke of the rural, provincial origins of their families

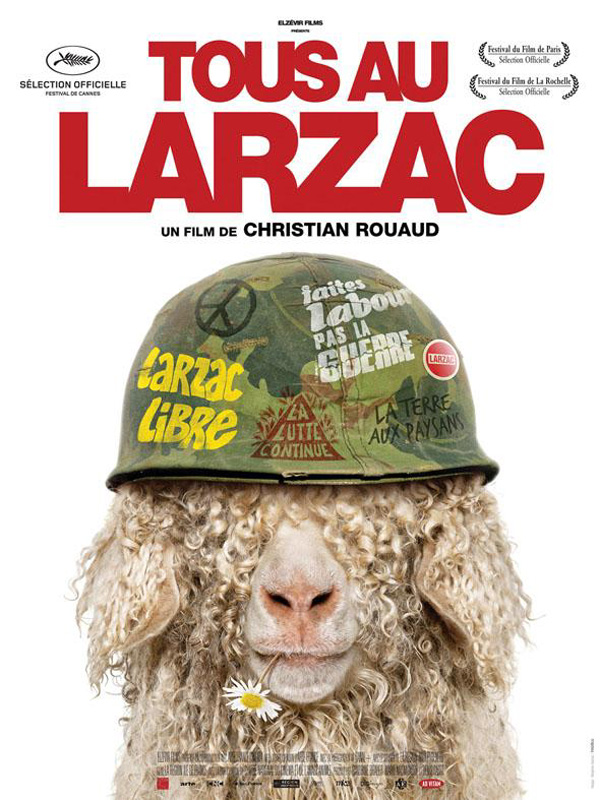

and perhaps owned a second residence in said province, but had no direct connection with what the word paysan evoked for them. In the 1970s, modernizing family farmers opposed to mass production agriculture, in conjunction with néoruraux, urbanites who reversed history by turning to farming, embraced the term paysan in formulating a representation of the, society to which they aspired. A revealing way to get at the paysan of collective memory and the paysan of collective action in the Fifth Republic is to think about who we see in Berri’s filmed adaptations of Pagnol’s novels and Christian Rouaud’s Tous au Larzac [Leadersheep].

and perhaps owned a second residence in said province, but had no direct connection with what the word paysan evoked for them. In the 1970s, modernizing family farmers opposed to mass production agriculture, in conjunction with néoruraux, urbanites who reversed history by turning to farming, embraced the term paysan in formulating a representation of the, society to which they aspired. A revealing way to get at the paysan of collective memory and the paysan of collective action in the Fifth Republic is to think about who we see in Berri’s filmed adaptations of Pagnol’s novels and Christian Rouaud’s Tous au Larzac [Leadersheep].

Pagnol (1895-1974) tells the story of La Bastide, a village in the Third Republic, which owes its existence to the decision by a summer resident from Marseilles to pipe water to what becomes the village center. Jean, another Marseillais, inherits land in La Bastide and moves there in search of “authenticity,” and finds without recognizing it, the paysans’ stereotypical love of land and money. Papet and his nephew Ugolin cheat Jean of the water on his land, leading to his death. Both Jean and Ugolin are driven by dreams of success in market agriculture—the first by raising rabbits and the second carnations. The fecundity absent from the aging peasant population itself inhabits these agricultural dreams.

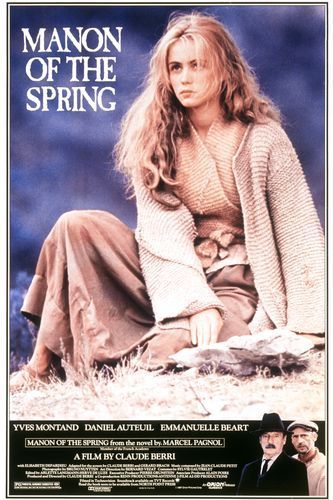

Berri wanted to present a peasant culture with an “authenticity” for his viewers as well. To assure this, he edited out the illegality in Pagnol’s account that maintains stability in La Bastide, i.e. poaching identified as such and reference to what amounts to prostitution; even Jean’s daughter Manon gathers rue, presented by Pagnol as an abortifacient, to sell. Berri also takes out Pagnol’s evocation of Jean as a figure of the globalization associated with the port of Marseilles, as his plans depend on the unusual qualities of squash identified in the novel as coming from Asia and a rabbit which Pagnol presents as native to Australia. However, for both Pagnol and Berri, republican politics are limited to anti-clericalism which suffers when the Church appears more effective than the village republicans or republican authorities in restoring water to the village. The novels and films present a world in which agriculture for external markets may increase the demand for water, but the loss of water comes only from the actions of individuals within the village. And in turn the village is premised on a solidarity marked by insularity and the expectation that none interfere in others’ affairs, particularly when recent arrivals to the village would benefit.

In Tous au Larzac, Rouaud tells a very different story in a different way. From 1971 to 1981, the sheep farmers of Larzac (Aveyron) successfully resisted army efforts to take their farms to expand a military base. As producers of milk used to make Rocquefort cheese, the farmers shared traits with the enterprising carnation and rabbit farmers of La Bastide. However, the state, not other peasants, threatened their ability to work the land. The Larzac farmers acted very differently from Berri’s and in so doing have played an important role in developing a new representation of the paysan in France. The movement owed its success to an ideology and practices with roots in a Left-wing Catholicism quite unlike the culture that Pagnol and Berri present in La Bastide. Furthermore, the Larzac farmers were open to outsiders who supported  them and to néoruraux like Confédération paysanne leader José Bové, who came from an urban world to set up farms in Larzac. As Tous au Larzac shows, the farmers of Larzac began to think of themselves not as an exemplar of the French past, like the paysans audiences saw in Berri’s films, but as sharing experiences and interests with smallholding peasants internationally today. When the farmers of Larzac adopted the term paysan, it had become for many in France a denigrating term connoting a lack of sophistication like that displayed by Ugolin, mystified by Jean’s reference to the “authentic,” which he could only take to be an unknown crop. Rouaud’s film shows the farmers of Larzac creating a systematically different representation of paysan.

them and to néoruraux like Confédération paysanne leader José Bové, who came from an urban world to set up farms in Larzac. As Tous au Larzac shows, the farmers of Larzac began to think of themselves not as an exemplar of the French past, like the paysans audiences saw in Berri’s films, but as sharing experiences and interests with smallholding peasants internationally today. When the farmers of Larzac adopted the term paysan, it had become for many in France a denigrating term connoting a lack of sophistication like that displayed by Ugolin, mystified by Jean’s reference to the “authentic,” which he could only take to be an unknown crop. Rouaud’s film shows the farmers of Larzac creating a systematically different representation of paysan.

Tous au Larzac is not the first documentary on Larzac. The Larzac farmers’ organization co-produced Philippe Cassard’s La Lutte du Larzac 1971-1981 in 2000 and it remains the film available on the movement’s web site, larzac.org. Cassard collected super-8 footage from Larzac farmers and others and put it together to chronicle events. The soundtrack is provided by the comments and conversations of movement leaders in response to what they see in this footage. If it is not on contemporary film then it is not part of the story told. The viewer never sees the speakers nor are they individually identified.

However, the speakers’ names appeared on the cassette box of La Lutte du Larzac and from this, Rouaud compiled his initial list of people with whom to speak. He began by using a tape recorder to interview his subjects individually at length. Having pored over the 750 transcribed pages of interviews and used them to prepare a script, Rouaud then filmed his subjects, seeking footage that he could cut and splice to allow him to tell the story, what he calls the “fiction du réel,” that he had developed from the earlier interviews. And unlike the reverential treatment given the footage from the time of the conflict in La Lutte du Larzac, Rouaud on occasion speeds it up and slows it down, turning color footage into black and white.

Both Berri’s and Rouaud’s films are works of adaptation. Rouaud recognizes this in elements like the presentation of Marizette Tarlier at the gravestone of her husband, the movement leader Guy Tarlier, whose distraught response to the imprisonment of his wife for destroying documents to save farms is recalled elsewhere in the film. Rouaud tells an interviewer that one viewer told him Tous au Larzac was “a love story.” Those who saw the rough cut recommended he take the scene at the tomb out as extraneous, but he rightly refused. Viewed in light of the very male world of the peasantry in Berri’s films, Rouaud displays the peasant couple of the new paysannerie.

Rouaud is quite successful in making the men and women he interviews distinct individuals. He told an interviewer that what interested him in the story of Larzac was “the way in which such different people manage to build things together.” The very texture of the film explores the confluence of the representation of the family farm as a last site of independence in contemporary post-industrial culture and the commitment to the collectivity which allows it to remain so. The contrast is clear with Pagnol/Berri’s peasants who, to paraphrase Karl Marx, are as similar and uncooperative as potatoes in a sack, whose only shared interest is keeping the sack closed.

In 1978 Jean-Paul Sartre called the Larzac movement “la plus belle lutte de notre vingtième siècle,” evoking in aesthetic terms the authentic that he valued. Between the initial interviews and the final filming, Rouaud found himself watching Hollywood westerns. Thinking of the dramatic rock formations in the Larzac, reminiscent of those found in the American West, he wrote in the script of Tous au Larzac that he wanted to make the “paysage un personnage.” In his film, the land is the actor it was in the struggle, unlike the haphazard place it holds in contemporary footage. More important, Rouaud thought about the themes of westerns like the conflict of rights and laws and their relation to the story he wanted to tell. It would be “an action film,” “a non-violent western,” in which the Larzac farmers sometimes bring to mind the Indians in the way their land is taken, farming in the midst of military occupiers, having treaties (accords) broken, and, at other times, the settlers in the American West, forming new bonds of solidarity in a community under siege and participating in a new world in the making, with different codes and values. Berri’s peasants are bound and bind themselves as individuals to the land unlike those in Tous au Larzac for whom the land is the site of collective agency. Rouaud’s treatment of the landscape is illustrative of how the genre of the documentary can be opened up by drawing on the most expressive cinematographic languages. If Berri rightly won accolades for the beauty of his films, Rouaud’s triumphs through an intertextual display of a beauty which evokes that to which Sartre refers.

Pairing these films in a course in modern French history works well, both as an exploration of representations and practices of farming populations and as an analysis of the texts historians use. Screening Jean de Florette (if only one Berri film can be shown) and Tous au Larzac allow for a discussion of the rural actors’ cultures and ideologies and how they enact them in particular historical situations. Viewing the films together brings out the particularities of representations of the paysan in Fifth Republic France and encourages students to think about the nature of historical recreation. Both Berri and Rouaud adapt original scripts, whether novels or participants’ accounts, and craft a new narrative in which the real of the fiction confronts the fiction of the real.

Claude Berri, Director, Jean de Florette, Color, 1986, 120 min., France, Switzerland, Italy, Austria, DD Productions, Films A2, Radtiotelevisione Italiana (RAI)

Claude Berri, Director, Manon des souces [Manon of the Spring], Color, 1986, 113 min., Italy, France, Switzerland, DD Productions, Films A2, Radtiotelevisione Italiana (RAI)

Christian Rouaud, Director, Tous au Larzac [Leadersheep], Color, 2011, 120 min., France, Elvézir Films, Arte France Cinéma, Arte France