Brian Sandberg

Northern Illinois University

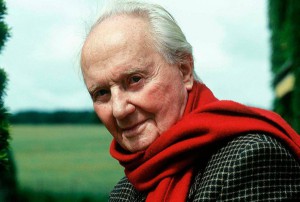

The Brethren and City of Wisdom and Blood are the first two installments (the third comes out in June) of a popular French series set during the Wars of Religion, Fortune de France. Robert Merle epic thirteen-volumes, published between 1977 and 2003, span the period 1547 to 1661, and is now being translated into English for the first time. The title of the series comes from a quotation from Michel de l’Hospital: “Shall we never see France’s fortunes reversed? Or shall we remain for ever despised and downtrodden?” (5). Merle grew up in French Algeria, then moved to Paris and began teaching English at a lycée in Neuilly-sur-Seine. He served as an interpreter for British forces during the Second World War, and wrote a novel about his experiences that won the Prix Goncourt in 1949.[1] The Fortunes of France constructs swashbuckling adventures across the historical landscape of sixteenth and seventeenth-century France, evoking Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers and attracting a loyal French readership.

Merle describes his work as a chronicle, but the novels actually blend together several genres of history and historical fiction. The first six are written as a first-person narrative by Pierre de Siorac, a minor noble from Périgord. But a third-person narrative voice sometimes takes over to chronicle events across France that Pierre could not have witnessed. Documents such as letters, notarial contracts, and the family’s livre de raison (commonplace book) are regularly featured, but the use of the latter at times seems anachronistic, more like a nineteenth-century confessional diary than a sixteenth-century account book or family chronicle. Merle relies heavily on contemporary or near-contemporary memoirs written by participants in the religious wars such as Blaise de Montluc and Pierre de Bourdeille, seigneur de Brantôme. He also interjects writings from contemporary writers and poets, including Étienne de La Boétie, Michel de Montaigne, and Pierre de Ronsard.

Merle describes his work as a chronicle, but the novels actually blend together several genres of history and historical fiction. The first six are written as a first-person narrative by Pierre de Siorac, a minor noble from Périgord. But a third-person narrative voice sometimes takes over to chronicle events across France that Pierre could not have witnessed. Documents such as letters, notarial contracts, and the family’s livre de raison (commonplace book) are regularly featured, but the use of the latter at times seems anachronistic, more like a nineteenth-century confessional diary than a sixteenth-century account book or family chronicle. Merle relies heavily on contemporary or near-contemporary memoirs written by participants in the religious wars such as Blaise de Montluc and Pierre de Bourdeille, seigneur de Brantôme. He also interjects writings from contemporary writers and poets, including Étienne de La Boétie, Michel de Montaigne, and Pierre de Ronsard.

The first novel, The Brethren, is the coming-of-age story of the protagonist, Pierre de Siorac, and takes place in the years 1547-1565. Pierre is raised on the small seigneurie of Mespech, a fictional estate near Sarlat. Pierre’s father Jean served in Italy as a captain in the armies of François I alongside Jean de Sauveterre, “his friend and steadfast companion” (13). After leaving military service in the 1540s, the two Jeans forge a brotherhood and purchase the estate at Mespech together, settling there along with three of their ex-soldiers. Locals begin referring to the two captains collectively as the “Brethren” because of their close bond as they establish themselves as minor noblemen in Périgord.

Merle draws on Annales school histories to paint a fascinating portrait of everyday life at the château de Mespech. The rhythms of the agrarian cycle are emphasized, for example in descriptions of summer haying. Periodic droughts and heavy rains ravage crops and contribute to famine, disease, and death in the Périgord countryside. The family’s notary Ricou comes regularly to draw up marriage contacts, codicils, and other notarial documents—which often become part of the plot (132). Pierre de Siorac shares passages from the family livre de raison, which feature dialogues between the two Jeans on major family events (52-53). The family servants and other locals speak the langue d’oc rather than the northern langue d’oil from which modern French derives. This highlights the profound particularism and regionalism in early modern France. The story builds a social history from the bottom up of seigneurial landholding, agrarian economy, and peasant culture in the rural setting of Périgord.

Pierre’s father and “uncle” Jean de Sauveterre both secretly adopt the Calvinist “new opinion” and continue to act as co-seigneurs, even after Jean de Siorac marries a Catholic noblewoman and the couple have several children. Pierre highlights the religious tensions within the family: “Between my father and my mother, almost from the first day of their marriage, there raged a small war of religion, which, whether latent or openly engaged, knew no respite” (54). The book depicts the rapid growth of Calvinism in southern France in the mid-sixteenth century, and how religious reform and heresy became divisive issues throughout the kingdom. Henri II’s persecution of heresy in the 1550s provoked fears among Périgord Calvinists. The two Jeans nonetheless continue to practice in secret and engage in clandestine Reformed worship. At the news of François II’s death in 1560 they stop attending Mass and openly proclaim their Calvinist faith (159-160).

The novel explores the religious life of this unconventional extended family, which includes several Catholic servants and artisans. The book captures some of the religious discourse of the sixteenth century through Calvinist discussions of faith, salvation, Providence, the pure Word of God, the Last Supper, and the service of God. The Catholic characters engage in religious practices such as prayer, invocations of saints, Marian devotions, and religious processions. Calvinists practice psalm-singing, engage in religious disputes and austere worship, but they also mock Catholic idolatry, “superstitions,” and “errors.” Calvinist characters at times promote “religious freedom” and “liberty,” promoting toleration in anachronistic fashion (164). The two Jeans eventually force their mixed-religion extended household to convert to Calvinism, but Isabelle refuses to submit and continues to practice Catholicism openly. Pierre de Siorac emerges as a reluctant Calvinist who is torn between his love for his Huguenot father and his loyalty to his Catholic mother. Pierre comments that “the cruel disagreement which split Mespech was but a feeble and tiny reflection of the disputes that raged at that time throughout the entire kingdom between Catholics and Huguenots, causing such passions, such tumult and, finally, such frightful civil wars that the fortunes of France were all but buried” (189).

The telling of war stories and the relating of war news provide opportunities to inform Pierre about political and religious developments in faraway Paris and throughout the kingdom. In the 1550s, Jean de Siorac takes up arms to serve in the campaign to retake Calais from the English. Merle inserts the famous medieval story of the burghers of Calais, famously depicted in the bronzes by Rodin (93-95). Siorac’s service in the king’s army led by the duc de Guise wins him the title of baron de Siorac. Once the French Wars of Religion break out in 1562, the countryside descends into chaos with nobles, brigands, and peasants fighting each other.

The telling of war stories and the relating of war news provide opportunities to inform Pierre about political and religious developments in faraway Paris and throughout the kingdom. In the 1550s, Jean de Siorac takes up arms to serve in the campaign to retake Calais from the English. Merle inserts the famous medieval story of the burghers of Calais, famously depicted in the bronzes by Rodin (93-95). Siorac’s service in the king’s army led by the duc de Guise wins him the title of baron de Siorac. Once the French Wars of Religion break out in 1562, the countryside descends into chaos with nobles, brigands, and peasants fighting each other.

Medical history plays a role in the plot of the Fortunes of France series, since Jean de Siorac has trained as a doctor and his son Pierre is destined to follow the same path. Jean frequently discusses medical concepts and occasionally practices medicine at the château de Mespech. The book discusses wet-nurses and breast-feeding extensively, with Merle offering long, voyeuristic descriptions of breasts and breast-feeding. The dangers of childbirth are shown through several stillborn births and the tragic death of Pierre’s mother, Isabelle, while giving birth. Plague epidemics periodically ravage the nearby town of Sarlat and the Périgord countryside, provoking fears at the château. The famous physicians Ambroise Paré and Nostradamus make an appearance in the book. Merle seems to overreach in having Jean de Siorac conduct an autopsy and advise the use of opium, which would not be readily available in Europe until European commerce with East Asia accelerated in the seventeenth century. In the second book, City of Wisdom and Blood, Pierre studies at the famous faculty of medicine in Montpellier.

Despite incorporating these historical dimensions, The Fortunes of France series unfortunately reinforces many stereotypes and outdated historiographical interpretations. The Valois royal court is portrayed as “a den of corruption” (383). The novel subscribes to the Black Legend of Catherine de Médicis as a conniving, dissimulating, and Machiavellian woman. “The niece of Pope Leo X, Catherine had inherited her uncle’s high forehead, bulging eyes and deep scepticism,” Merle writes (370). Later, the queen mother is described as “a snake groveling in the dust at her Spanish master’s feet” (393).

The Fortunes of France series does effectively showcase the atrocious violence of religious conflict and civil warfare. Southern France appears as a dangerous region where hostage-taking, ransom, and pillage became part of everyday life. The novels incorporate stock characters drawn from contemporary picaresque novels: gypsies, beggars, vagabonds, bandits, brigands, and spies. Early in the book, the wicked baron de Fontenac opposes the two Jeans’ plan to purchase the château de Mespech, but they outwit him and kill the Italian agent the baron sent against them, hanging his body upon a tree as a message to Fontenac (107). As the Calvinist movement gathers strength in southern France, Huguenot crowds engage in iconoclastic attacks and destruction. A religious middle ground emerges through the interventions of Étienne La Boétie, a Catholic moderate who questions Huguenot iconoclasm and aggression (190-194). Angered by massacres at Vassy and Cahors, Jean de Siorac and his son eventually join the Huguenot cause and engage in skirmishes, battles, and sieges, typical of this chaotic period. Meanwhile, the duc de Guise provides effective leadership for the Catholic cause early in the fighting, but the baron de Montluc displays cruelty in pursuing Huguenots in Périgord. The narrative presents torture, maiming, and summary execution as normal aspects of religious warfare. But the experience of combat shakes young Pierre, who questions killing and begins to doubt his commitment to the Huguenot cause.

Despite some errors, Robert Merle paints a rich tapestry of sixteenth-century France in the volumes considered here. Where Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers depicts violence primarily through dueling and gallant adventures, Merle concentrates on pervasive raids, ambushes, and assassinations. The Fortunes of France presents an imaginative fictional recreation of the French Wars of Religion that should interest readers who are fascinated with French history or curious about religious conflict.

Robert Merle, The Brethren and City of Wisdom and Blood, translated by T. Jefferson Kline (London: Pushkin Press, 2014-2015).

NOTES

- Dalya Alberge, “Historical Epic of France’s Hilary Mantel Finally Crosses the Channel,” The Guardian, 16 August 2014.