Elena Russo

Johns Hopkins University

Who’s afraid of Marivaux? Quite a few people, it turns out, especially those who ought to know better. Late this spring, I was being treated, by a lovely friend, to a front-row seat at the Paris Odéon theatre where they were showing Les Fausses confidences with Isabelle Huppert as Araminte, and was counting myself blessed. But when my friend and I emerged from the theatre we did not feel so much like thanking the gods, as grabbing the director by the ear, sitting him down, and giving him a piece of our mind.

What was the point of the whole performance? What was he thinking? Why put on a play by Marivaux if you don’t trust the text, if you instruct the actors to play as if they didn’t believe one word of it, as if it were all one big, fat, hysterical farce? But the audience had seemed happy and had applauded heartily. Then I was reminded of a pertinent remark I had read about Abdellatif Kechiche’s acclaimed movie L’Esquive (2004) and Kechiche’s successful appropriation of marivaudian themes: “Marivaux’s language is as foreign to well-to-do Parisians as it is to banlieusards.”[1] But, the author had added: “As such, it belongs more readily to all.”

To all? To Kechiche, for sure. For he has succeeded in revealing its chameleonic potential and in populating Marivaux’s world with his own creatures, who live and breathe alongside Silvia, Dorante, Lisette and Arlequin. It’s true that an act of intertexual appropriation such as L’Esquive offers a freedom and versatility that are not available to a director who is putting up a theatrical production, and that it would be unfair to compare the two procedures. But I am not going to. What I’d like to do here is have a second look at L’Esquive. Literally so, in fact, because when I first saw it, about ten years ago, I was intrigued and overwhelmed by the youths’ mode of interaction. As my father asked one day that I was playing a tape of Puccini’s Tosca in the car: “But why are they yelling so much?”

I’d like to explore to what extent Kechiche’s claim “I wanted my characters to live a marivaudge” comes true in the movie.[2] Not in hopes of making a case for the relevance of Marivaux to contemporary culture (after all, Marivaux may well be a mid-20th-century author, for that’s when he first found his most qualified and receptive audience), but to ask – and perhaps it comes down to the same – what, if anything, playing Marivaux brings to the young people portrayed in the film.

I’d like to explore to what extent Kechiche’s claim “I wanted my characters to live a marivaudge” comes true in the movie.[2] Not in hopes of making a case for the relevance of Marivaux to contemporary culture (after all, Marivaux may well be a mid-20th-century author, for that’s when he first found his most qualified and receptive audience), but to ask – and perhaps it comes down to the same – what, if anything, playing Marivaux brings to the young people portrayed in the film.

I should add that my reading intentionally eschews the explicitly political readings that have been done very well elsewhere. Marivaux’s political message is real, but always intimate and elusive. So too, in this movie, is Kechiche’s.

Much has been said about the fruitful encounter between Marivaux’s idiolect and the multi-cultural idiom of the banlieues. Of course, we should not make the mistake of thinking that there are two separate spaces: that of the banlieue, a site of politically competing, contested representations, of authentic language, of life as it is; and that of theatre, with its highly ritualized language and conventions.[3] For the originality of L’Esquive is that the kids’ space is already inherently theatrical in a true marivaudian sense, and that their language is as much a cultural construct as that of Marivaux. The dialogue, Kechiche explained, was fully scripted and its language was the product of a collaborative effort between the director and the young actors, some of whom were kids from the milieu portrayed in the movie.[4] Let me briefly recap the plot’s main premises.

Fifteen-year old Lydia is heading to a small, open-air amphitheatre, in her cité, where she’ll rehearse Le Jeu de l’amour et du hasard for a school performance. Arguably Marivaux’s quintessential play, the plot features role-playing as Silvia and Dorante, betrothed without having ever met, decide, unbeknownst to each other, to switch places with their servants (Lisette and Arlequin), so as to be better able to study each other’s behavior. Before the game is over, and everybody is unmasked and back to where they belong, the rich and proud Silvia must endure the awful thought that she has fallen in love with a manservant. That said, let us keep in mind that Marivaux’s play is embedded in L’Esquive, but not mise en abyme, not refracted. The real and profound encounter between Kechiche’s dramatic language and Marivaux’s takes place at an entirely different level, as I will argue.

Lydia plays Lisette; her classmate and friend (frenemy, more like) Frida plays Silvia; classmate Rachid is Arlequin. When Lydia’s old friend Krimo, a shy, reserved fifteen-year old, runs into her, and is invited to watch the rehearsal, we guess that something akin to a surprise de l’amour is happening to him, in real time. Seeing Lydia gyrating, enchanted by her own looks, in her eighteenth-century costume, perhaps does it; having just been dumped by his fiery and jealous girlfriend Magali, likely does it too. But Krimo’s facial expressions are not very revealing, and he never says much. Eventually Krimo bribes Rachid into relinquishing his role as Arlequin in his favor. We can guess why; but surely Krimo had other chances to see Lydia, besides joining her on the rehersal stage, mumbling his lines in a dull monotone, and finally trying to kiss her so awkwardly that they both fall backwards, legs kicking the air. “What got into you?,” asks Lydia, who acts surprised, but (we know for a fact) had seen it coming. “Nothing…Just to go out with you, that’s all,” Krimo replies (1043). “Alors? Alors tu veux?,” he insists.[5] But Lydia says she doesn’t know, and asks for some time to “reflect.” She is going to call him from home. “À quoi ça sert qu’tu gâches des unités…” (why waste your minutes), Krimo asks ruefully, in one last-ditch effort (1065). Lydia’s request to take the time to think about it, is perceived as shockingly transgressive: the rest of the movie will explore why.

If playing Marivaux turns out to be such a big disruption in the little community, it’s not because the kids of the banlieue do not “get” theatre. Most of them get it very well. Rachid, in particular, a sturdy, self-assured boy – safely provided with a girlfriend, Hanane, who attends the rehearsals – is perfectly at ease in Arlequin’s role. (In Marivaux’s play Arlequin is, of course, a servant impersonating his master, intent on seducing a servant girl who impersonates her mistress.) Rachid with large, showy gestures, cleverly overplays the seduction part, kisses Lisette’s hand, tries a kiss on her cheek, while she shields herself from him with a fan (“je l’esquive”); all that in front of Hanane, who does not dream of being jealous and has no fear that Rachid is going to lose his masculine standing. Frida rebukes Lydia for her excessive investment in her costume and enjoins her to “vivre les sentiments des personnages.” And Lydia loves every minute of it, strenuously fanning herself and sashaying on the stage.

But Krimo is the odd boy out; he just doesn’t get it, and soon the trouble that is surging inside spills all around him. In the classroom, in front of his schoolmates, Krimo’s habitual reserve turns to complete paralysis. When the teacher tells him that his delivery is dull, and asks for more “joie de vivre,” because Arlequin is young and in love, she does not know how close to the truth she is. As an actor, Krimo sucks–“il puait la merde,” says Nanou, a friend of Lydia. The problem with Krimo is one that Marivaux and Diderot both knew and wrote about: he means what he says. Unlike Rachid, Krimo is not acting, he is being himself. Or rather, being himself prevents him from acting. Krimo must play a character who is in love, but the fact that he himself is in love with the actress playing his fictional love object gets in the way.

To make his situation worse, Krimo is reciting at this point one of the most jargony, challenging lines in the play. No one bothers to explain to him what Arlequin means when he stretches and strains his metaphors.[6] Certainly not the teacher, who is too busy delivering a sweeping, crude sociological analysis of the play’s political message to realize that Krimo is clueless. Instead, she throws at him well-meaning, inspirational speeches about acting that only stump him more. But when she prods him: “Embrasse cette main, amuse-toi! Libère-toi… Donne-toi!” (1228 and1233), there is a cruel irony to in her words, unbeknownst to her.[7]

Krimo, lost in an unfamiliar “feminine” world (for some of the kids see the theatre as female, or worse, as effeminate), finds himself in a hopeless bind: unable to utter the words he would like to say to Lydia, he is made instead to channel his feelings through the highfalutin chatter that Arlequin mistakes (half-mistakes, for Arlequin is no fool, but that’s another story) for the language of the masters. It’s no wonder that he seeks to end his ordeal by quitting and slamming the door behind him.

Krimo’s life is largely dominated by Fathi, an older swaggering bully who is used to beating girls. Fathi’s and Krimo’s relationship displays some seigneur-vassal dynamics. Fathi takes his subordinate’s “best” interest at heart, initiates him to porn movies, and supervises his love life, unaware of the boy’s break-up with Magali (whom Fathi sees as the “right woman” for him) because Krimo hasn’t dared to tell him. Eventually, Fathi is updated by Slam, a boy in Krimo’s and Lydia’s class. Krimo is in trouble! “He is making a fool of himself for a girl who won’t even say yes or no, flat as a board, no tits or ass, nothing, pure crap!” And yet he is groveling at her feet, acting like a buffoon: he is doing theatre! “Get out of here! that’s horseshit,” replies Fathi, outraged: no way a boy like Krimo would ever do anything like that! “On my mother’s head, I am telling you the truth!” Slam protests. “He’s acting in a play, you know, the old-fashioned kind, like, in the Middle Ages.” “Like a fag,” he concludes (1133-1143).

Does the girl like him at least? Fathi asks: “Et elle, elle le kiffe ou quoi?” To which Slam answers, with perfect authority: “Franchement, j’vais te dire la vérité, j’crois pas… Elle l’allume, elle l’allume, elle le chauffe mais elle le kiffe pas.” (1153)] [8] If she did she would say yes, instead of pushing him to such depravity.

The youthful world in which Lydia, Krimo and their community operates is ruled by strict laws, with as little space for equivocation as possible. It is public and theatrical; actions and values are negotiated and discussed constantly, so that anyone may be a judge of everyone else, and possibly an enforcer of the law. Feelings overflow the strict constraints of a language that is made of value-laden words that carry more affect than content, because they signify rejection or acceptance, approval or blame. Pute, for instance, covers a wide, poorly defined range of female transgressions: being disloyal; being late; keeping things to yourself; being too much of a flirt, etc. It’s all the more threatening as it is broad, but categorical. It’s all or nothing; either/or. The kids’ vocabulary does not allow them to modulate and distance themselves from their emotions, which are often raw. Style tends to be hyperbolic – “T’es folle, toi?” or “t’es malade?” will preface a polite refusal to accept an invitation to the movies because “are you crazy? I have a lot of work” – or antiphrastic, with negatives being used to express approval (as in “une bête de meuf,” a terrific woman). One of the iron rules that should not be broken is that when a boy, or a girl, asks someone out, the person who is asked doesn’t dawdle, procrastinate, evade, skid around the issue: in other words, she does not practice the “esquive,” the art of avoidance and equivocation. Uncertainty and ambiguities are taboo in this small society run by the boys’ fear of losing face and submitting to the whims and desires of the girls. And the girls largely accept it, as a principle. But of course, practicing what one preaches is quite another matter: for how can the heart submit to such binding transactions? Thus, when Magali breaks up with Krimo and calls him names (“sale connard, va!… enculé,” (59-61) she does not quite mean what she says. She is getting back at him because she feels neglected. Eventually, she thinks, they’ll make up. Instead, Krimo feels fine about the breakup, though he doesn’t tell her, and perhaps he is not quite aware of it yet. Their mutual méprise (misunderstanding) will thus trigger a series of reactions, for everything in this movie is constructed like a classical play: unity of action, time, place.

Soon after the breakup, Magali confronts Lydia, in front of her girlfriends, and accuses her of being a tease and a slut, and of trying to steal her boyfriend: why would a guy like him, who never opens a book, decide to do theatre? “Tu touches pas à ce mec, il est à moi, t’as compris? […] tu fais pas ta petite allumeuse…”(682-83) “J’suis pas une voleuse de gars, moi,” Lydia protests. (662) [9] That scene is tense, rife with hostility and hurt feelings. Most critics have ignored it, and in so doing, they have taken away an essential piece of the puzzle that constitutes the dramatic core of the play. Without the pressure enacted by Magali, we cannot understand the reasons for Lydia’s hesitation concerning her feelings for Krimo, nor can we understand that, in true Marivaudian spirit, Krimo appeals to Lydia as much because he is a contested, forbidden object, as despite the fact that he is one.

But Lydia, contrary to what people are saying, is not a tease who fancies herself to be a Lisette.[10] In Kechiche’s movie, as in most of Marivaux’s plays, the heroine finds herself at a crossroads, torn between several pressure points that result in conflicting feelings and irreconcilable ethical choices. Marivaudage is not simply bantering, as has been said too many times: it’s a crisis that builds up gradually, explodes, and finds a resolution. Whatever bantering there seems to be is not flirty wordplay, but negotiation. That’s why L’Esquive feels so “Marivaux,” in a deep sense: to Lydia, esquiver is no mating game. In the rule-bound world of the cité (a world that’s just as constraining as that of Marivaux’s upper-class, sheltered heroines) Lydia is trying to find a private space to understand what she wants, while carefully skirting the rules that dictate how a woman should behave.

In this movie, the girl-on-girl conflict has largely been ignored in favor of the boys vs. girls conflict. In reality, both axes intersect, at several crucial moments, and Lydia finds herself stuck in the middle. Sitting on a bench, or perched atop of it, Nanou, Frida, Hanane and Lydia spoon or embrace, enfolded into one another like a polymorphic organism. Yet, faced with Magali’s challenge, the girls’ loyalties swing abruptly from one contender to the other, as they sympathize in turn with the hurt feelings of Magali or of Lydia.[11] Later on, after Fathi has brutally taken Frida and her cellphone as hostages (for he intends to use Frida in order to put pressure on Lydia to declare herself), an angry, tearful Frida spits back at Lydia the accusations she heard from Fathi. Nanou, the level-headed one, sides now with one, now with the other of her two friends, but beneath the vehement, foul language, there is an effort to clarify, to understand, to manage the conflict.

Much like the boys, Frida and Nanou press Lydia to reveal the truth, to level with them: did Krimo ask her out? Did she say yes? Why didn’t she tell Nanou, her best friend, that Krimo had asked her out? And why hasn’t she given Krimo an answer? “Espèce de p’tite pute! Tu vois comment t’es?” calls out Frida, exasperated: “T’es pas nette, putain, même avec nous t’es pas nette… Tu nous l’as même pas dit…” (1443). And, worst of all: “Tu veux trop te faire désirer toi, c’est pas bien.”(1466)[12] But Lydia protests: what about Magali? She still loves Krimo. No, Nanou and Frida rebut, don’t try to hide behind that excuse! In the end, they decide that calling Magali is the right course. It’s time to tell her outright to let go of Krimo: he no longer loves her, and she is just making trouble for everybody. “S’il kiffe une autre meuf, et que la meuf elle a besoin de faire les choses proprement […] t’as pas à faire tes coups de pression… ça se fait pas ça.”(1478-1481) [13] Those are the rules; he can’t mess with them.

The drama explodes with Fathi’s brutal, clumsy intervention, the last link in the chain of actions and reactions that shapes the plot: his manhandling of Nanou and Frida, of Krimo and Lydia, whom he throws together into his car so they’ll finally sort out this mess right there and then. But Fathi’s plan flounders when three cops descend upon them, bringing malice and hellfire, like diaboli ex machina. Follows a long, excruciating scene that grabs you by the throat and is abruptly cut when the camera releases you, shifting to a stage full of young children, doting teachers in the wings, smiling parents in the audience – including Fathi and Magali, who hugs a new boyfriend! It’s the day of the performance. As if it was left to the theatre to patch up all conflict and heartbreak, to bring some peace. But Krimo is not there. He is outside; he puts his forehead to the glass door, for a moment, and then walks away, like a stranger.

I want to go back to my initial question: what does the experience of the theatre, of Marivaux’s theatre in particular, do for the kids? What do they take from it, and what do we, as spectators, take from it, above and beyond the opening up of a space of irony and self-questioning? Marivaux does not exactly bring his language to these youths: the one they have, however grating it may sound to us, serves them fine. What he brings to them, to Lydia (who is the main vector) and to the other women, is a new grammar of human relations. The suggestion that the rules your friends defend and enforce may be broken; that pressures may be resisted. Lydia insists that she has the right not only to say “yes” or “no” (no one will begrudge her that), but also that of “reflecting,” of taking her time, of saying “maybe;” of evading constraints, skirting around obligations; the luxury of doubt. But those are rights that the boys do not want the girls to have because, to a greater extent than the girls, the boys need clarity and certainty: they want to know where they stand, not only because they need to keep the peace, but also because they don’t want to work too hard to get a girl. If a girl says “maybe,” or “it depends,” then you’ve got to seduce her, try to please her. Sooner than you know, she’ll have power over you, the kind of power that can make you miserable.[14]

But that’s how revolutions start, Marivaux seems to be telling us: with a sudden swerve, a new twist in human relations. Avec une esquive.

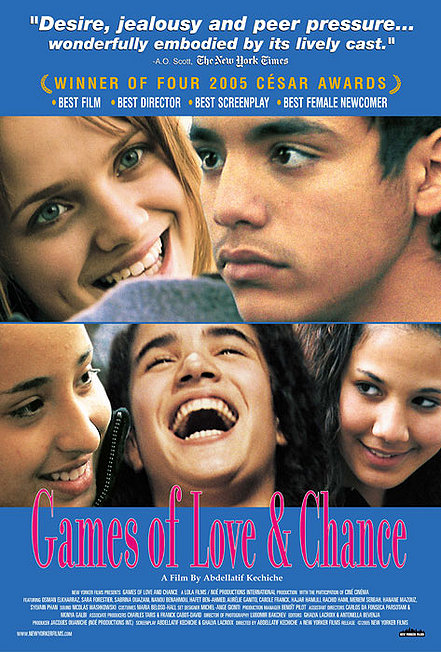

Abdellatif Kechiche, L’Esquive [Games of Love and Chance], France, 2003, 123 min, Lola Films, Noé Productions, CinéCinéma

NOTES

- Louisa Shea, “Exit Voltaire, Enter Marivaux, Abdellatif Kechiche on the Legacy of the Enlightenment,” The French Review, vol. 86, n. 6, May 2012, p. 1136-1148.

- “Je voulais que mes personnages vivent un marivaudage.” Kechiche also felt that “Cette jeunesse n’a pas de place dans le paysage audiovisuel.” A propos du film ‘l’Esquive’ d’A. Kechiche.” Interview by Michaël Melinard, L’Humanité, 7 January 2004, p. 18.

- “Ça me faisait plaisir de mélanger les deux formes de langage. J’aime beaucoup le langage de Marivaux mais j’aime beaucoup celui de ces jeunes que je trouve très inventif.” Ibid.

- “I had to do a great deal of work during the casting phase to get the language right. I gave the young people a great deal of freedom during the rehearsal period to explore the best way of saying certain things. That was work that we did together. Once shooting started, however, the script was fixed and we didn’t deviate from that.” “Marivaux in the ‘Hood: An Interview with Abdellatif Kechiche” by Richard Porton; Cineaste n. 31, Winter 2005, p. 46-49.

- “Qu’est-ce qui t’a pris, là ?” “Rien… Juste sortir avec toi, c’est tout.”

- “Prodige de nos jours,” Arlequin tells Lisette, “un amour de votre façon ne reste pas longtemps au berceau; votre premier coup d’ail a fait naître le mien, le second lui a donné des forces, et le troisième l’a rendu grand garçon; tâchons de l’établir au plus vite, ayez soin de lui puisque vous êtes sa mère.” Le Jeu de l’amour et du hasard, II, 3.

- “Kiss this hand… have fun. Free yourself.” The script was published in L’Avant-scène: Cinéma, n. 542, May 2005, p. 10-91. References are to the number of each frame.

- “I’ll be straight with you. I don’t think so. She provokes him, she fires him up, but she doesn’t care for him.”

- “Magali: lay off this guy, he’s mine, got it? Don’t act the little tease.” To which Lydia retors: “I don’t steal guys, me.”

- Michel Boujut is typical of the (quite sexist, if you ask me) trend. See “Lisette de Banlieue,” Avant-Propos to “L’Esquive,” in L’Avant-scène: Cinéma, n. 542, p. 1.

- Frida’s sympathy is for Magali: “Mais comprenez-la, putain de merde, comprenez-la! Vous êtes des meufs ou quoi? Z’avez un coeur, oui ou merde?” (711) – but Nanou redirects it towards Lydia: “Casse-toi, elle fait des embrouilles pour rien… Même à cause d’elle [Magali], on s’embrouille entre nous… Mais jamais!” (714)

- “You see how you are, little slut? You are not straight, even with us, you haven’t told us… You want too much to be desired, that’s no good.”

- “If he loves another girl and that girl needs to do things properly…you shouldn’t pressure her…it’s not done.”

- “Si tu restes avec elle, tu vas partir en couilles,” Fathi warns Krimo about Lydia: “Elle va t’apporter le malheur.” (1270-71). (If you stick to her, you’ll be ruined; she’ll bring you grief.)