Jeffrey S. Ravel

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The theater of the Old Regime and the French Revolution can be used to great effect in the undergraduate history classroom.[1] The plays of Molière and Beaumarchais introduce students to the absolutist politics, social inequalities, and mordant humor of prerevolutionary France. Reasonable English translations exist of some of the more popular boulevard and Théâtre de la foire plays of the second half of the eighteenth century, as well as some of the most controversial and provocative stage offerings of the revolutionary decade.[2] While careful readings of twentieth and twenty-first century editions of these plays in translation invoke major themes of seventeenth and eighteenth-century French history, they do not by themselves allow us to recapture the many  meanings of live theatrical performance in France before 1800. Theater during the Old Regime and the Revolution was a multi-media phenomenon, experienced by French men and women as a print or manuscript text to be read as well as an ephemeral performance moment. These theatrical encounters occurred in a variety of public, semi-public, and private spaces in Paris, Versailles, the provinces, and the colonies.[3]

meanings of live theatrical performance in France before 1800. Theater during the Old Regime and the Revolution was a multi-media phenomenon, experienced by French men and women as a print or manuscript text to be read as well as an ephemeral performance moment. These theatrical encounters occurred in a variety of public, semi-public, and private spaces in Paris, Versailles, the provinces, and the colonies.[3]

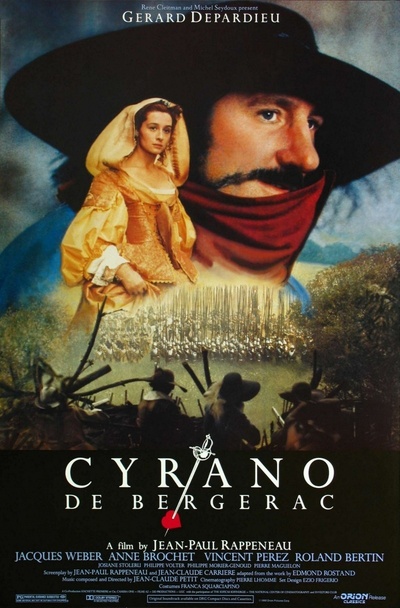

The challenge for the classroom teacher is to sensitize the students to the differences between the surprisingly interactive performance experience in France 250-350 years ago, and the distinctly tamer variant of live theater that we encounter in most playhouses today. Since its premiere in 1990, I have occasionally shown students the first 15 minutes or so of Jean-Paul Rappeneau’s film version of the Edmond Rostand stage classic, Cyrano de Bergerac. In this opening segment, Rappeneau and his actors recreate a live performance in a Parisian public theater of the 1640s. In the past year, I have preceded this film clip with a PowerPoint presentation of a series of engravings and other images of seventeenth-century Paris theaters that help students better understand the many historically specific details captured in the film. In my PowerPoint presentation, I stress three themes: the architectural peculiarities of Paris playhouses of the Old Regime, the characteristics of the different sections of those theaters, and the comparison between the public theaters and the performing spaces at the court of the kings of France. Once we have looked carefully at engravings and other still images of theaters in this period, we are ready to appreciate Rappeneau’s filmic version of an admittedly turbulent evening in a seventeenth-century Paris public theater.

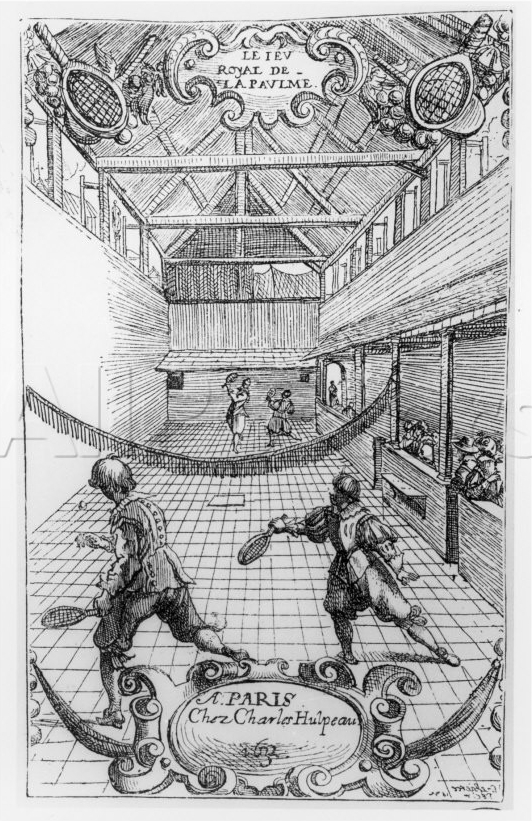

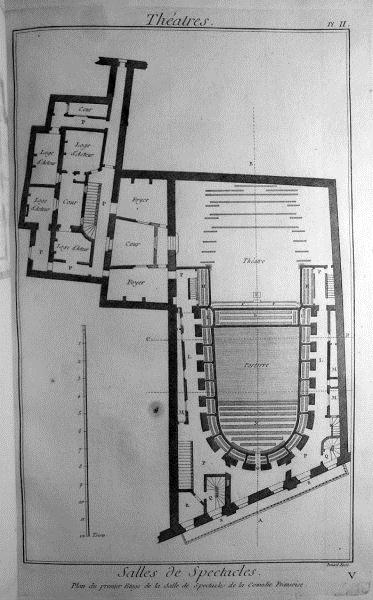

I begin with an image of an early seventeenth-century jeu de paume. Paris did not have dedicated public performance spaces where standing troupes regularly performed until about 1630, almost half a century after such theater buildings appeared in London and Madrid. Until then, ambulatory troupes would rent vacant indoor tennis courts, which were increasingly out of fashion among the Parisian nobles whose functions and pastimes were changing under the Bourbons. The oblong shape of these tennis courts influenced the first permanent theater buildings in the French capital, as one can see in this overhead view of the left bank building in which the Comédie-Française performed from 1689 to 1770.

Overhead view of the Comédie-Française playhouse, 1689-1770, from Recueil de planches sur les sciences, les arts libéraux, et les arts méchaniques, avec leur explication, vol. 9 (Paris, 1772)]

I ask the students to think about how well spectators sitting in the loges on either side of the auditorium would have been able to view the stage. I then ask them to think about how easily these same spectators could observe what was happening in the loges on the other side of the hall, or in the pit below them. Loge occupants were much better placed to observe the spectacles in the boxes and the parterre than on the stage itself, which tells us something about audience expectations in the period.

Another important difference between theatergoing in the age of Molière and today was the presence of spectators on the stage itself. These tickets were the most expensive ones available, for reasons I ask the students to ponder. Someone usually comes up with the idea that people of means wanted to display themselves at the theater in the most conspicuous way possible. I then recount anecdotes from the period of men who would engage in banter with the actors and actresses during the performance, walk across the stage in the midst of comic or tragic scenes, and generally do their best to provoke audience members in other parts of the hall.[4] I then show the students two seventeenth-century images of stage performances where the players are competing with the spectators on stage for audience attention.[5] These visual and textual examples usually lead to entertaining discussions about different aesthetic expectations exhibited by past spectators; in some instances, we discuss why seventeenth-century audiences did not share the same illusionistic expectations of theatergoers today.

After pointing out these features of seventeenth-century playhouses that appear so unusual today, I make a point of explaining to the students that the same troupes that performed in these public theaters also entertained the Bourbon kings and their followers at court in the 1600s and 1700s. Playwrights in the period knew they were writing for audiences in at least two substantially different settings, and the best ones, like Shakespeare in an earlier period in England, were able to craft entertainments that had something for all potential spectators from the king to the lackeys who snuck into the public theater spaces of Paris.[6] I tell the students to study Michael van Lochon’s 1641 engraving Le Soir, which depicts Louis XIII and Anne of Austria in the playhouse constructed in the residence of Cardinal Richelieu. Reminding them of our previous discussion about the focus of audience attention in the public theaters, I ask them where the focus of attention lies in this theatrical space, pointing out that many of the spectators in the balcony are gazing at the royal couple and Richelieu, rather than the performers on stage, and that the stage itself is eclipsed in the composition by the cardinal-minister, the king and the queen.

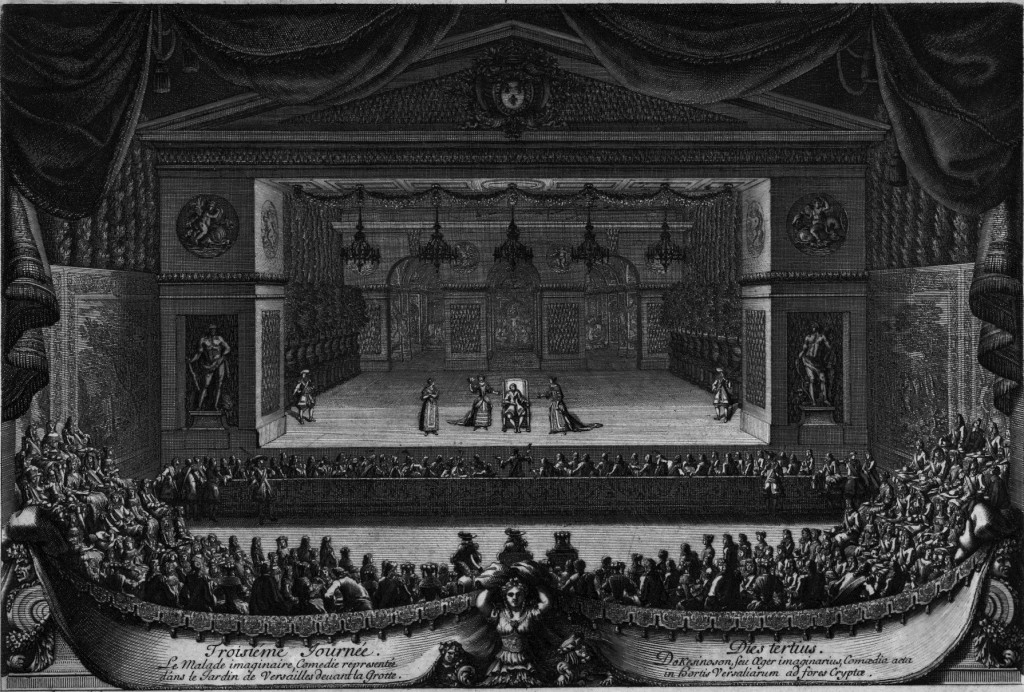

Jean le Pautre, Troisième journée, from André Félibien, Les Divertissements de Versailles donnez par le Roy à toute sa Cour au retour de la conqueste de la Franche-Comté en l’année MDCLXXXIV (Paris, 1674).

To drive home the point, I then show them the Jean le Pautre engraving of the performance of Molière’s Malade imaginaire during the cycle of court festivities in 1674 intended to celebrate the reconquest of the Franche-Comté. Here we see, a generation later, a far more grandiose courtly theater, but the dynamic of the royal gaze remains the same. The King enjoys the best seat in the house, one that enables him to comprehend fully the illusion created by the union of set design, the costumes, and the performance of the troupe. Louis’s courtiers are situated in such a way that they can observe the monarch’s reactions to the spectacle more easily than the spectacle itself. I then conclude this section of the presentation by pointing out that the place occupied by the monarch in the royal theaters becomes the parterre in the public theaters, the space inhabited by the crowd of standing male spectators who paid the cheapest price of admission. We speculate together on why this was so, and I discuss whether it was inevitable that this section of the audience hall would eventually be seated and cost more to enjoy than any other part of the theater. We also talk about why spectators sitting along the length of the auditorium in both public and royal playhouses did not demand a better view of the stage itself.

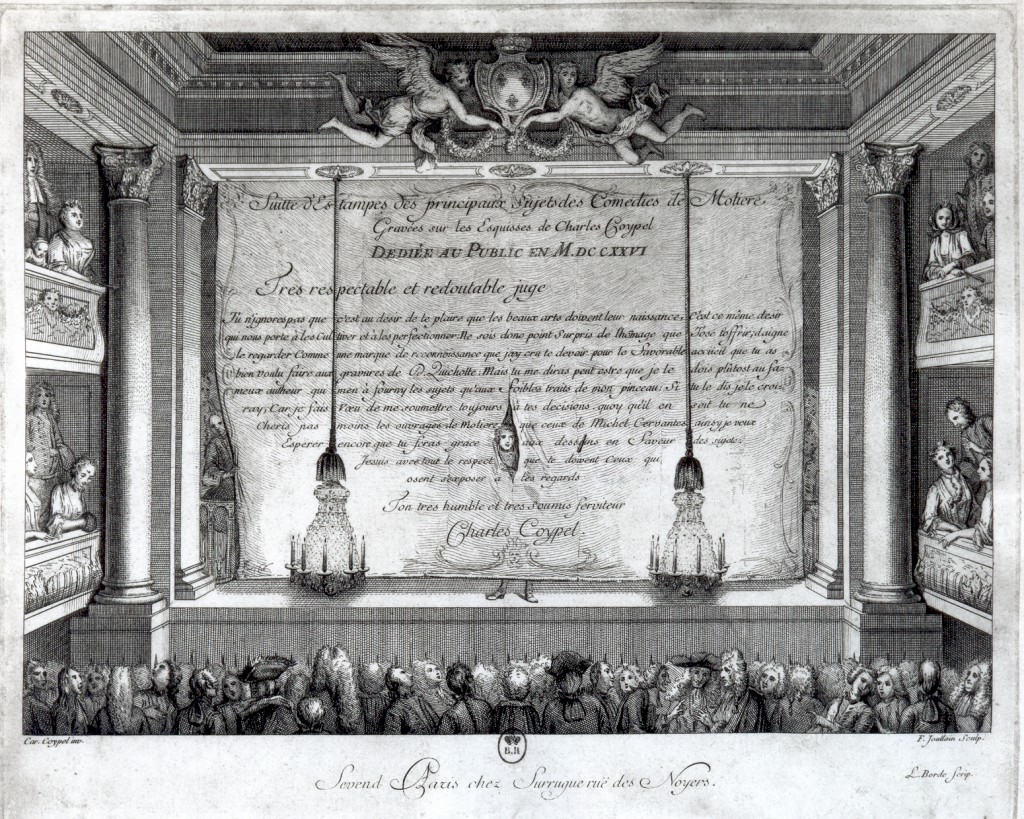

I conclude the powerpoint presentation with an image from 1727, a half century after the Sun King’s courtly spectacle, in which the artist and playwright Charles Coypel represented a Parisian public theater full of spectators just before the curtain rose on the evening’s performance. This image, dedicated to the theatergoing public as the text on the curtain tells us, served as the frontispiece to a multi-volume edition of plays by Molière that Coypel illustrated. The image suggests changes in the evolution of the theater public from the time of Molière to the early career of Voltaire, in that it shows a more orderly audience that divides its attention between the upcoming stage performance and the spectacle already under way in the audience. Spectators seated on the stage peak from behind the curtain to observe the men in the parterre, some of whom in turn ogle the women in the loges. But I also remind the students that this image was intended to draw readers into a private engagement with the texts left behind by Molière, thus emphasizing the theater’s dual role as a textual and performative medium.

Charles-Antoine Coypel, Frontispiece d’une suitte d’Estampes des principaux sujets des comédies de Molière, 1726.

Once we have worked our way through these images, we are better ready to appreciate the movie version of a Parisian public theater created by Rappeneau, the omnipresent Gérard Depardieu in his pre-Putin phase, and the other members of the 1990 film ensemble. The movie begins with a shot of a carriage rumbling towards a theater on a rainy Parisian night. Soon the tumultuous street scene invades the theatrical space. The ticket-takers stationed at the entrance to the building are overwhelmed by the crush of people jamming into the playhouse, many of whom refuse to pay the price of admission. Once inside, the audience vocally clamors for the start of the play amidst much drinking, eating, and gambling. The male spectators seated on the stage preen for the assembled masses before them, then attempt to defend the ill-fated actor Montfleury, whom Depardieu’s Cyrano attacks for his miserable style of acting. In one of my favorite touches, anachronistic perhaps but highly amusing, a young rogue in the upper balcony whips the wig off the head of one of the august members of the Académie française, seated just to the left of the stage, exposing his bald pate to the guffaws of the pit. I usually let the movie run through the duel between Cyrano and Valvert in which the latter is impaled on Cyrano’s sword, because the fight scene is so entertaining and because there is no natural stopping point before the end of the duel. Having closely considered the spaces of Old Regime playhouses in still images, and then seen the masterful depiction of one of these spaces in the film, the students are better prepared to understand the many political, social, and cultural meanings of the French stage in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Jean-Paul Rappeneau, Director, Cyrano de Bergerac (1990), Color, 137 min., France, Caméra One, Centre National de la Cinématographie, DD Productions.

- In Spring 2011 I structured a survey of French history from 1660 to 1815 in part around a series of play texts and their performances. See this link.

- For translations of boulevard and fair plays, see Daniel Gerould, ed., Gallant and Libertine: Divertissements and Parades of 18th-Century France (New York: Performing Arts Journal, 1983); for Jean-Louis Laya’s notorious revolutionary play L’Ami des lois, see Marvin Carlson, trans. and ed., The Heirs of Molière: Four French Comedies of the 17th and 18th Centuries (New York: The Martin E. Segal Theater Center, 2003); and for Olympe de Gouges’ L’Esclavage des noirs, ou L’Heureux naufrage (1792), see Doris Y. Kadish and Françoise Massardier-Kenney, eds., Translating Slavery, Vol. I. Gender and Race in French Abolitionist Writing, 1780-1830 (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2009), 2nd ed., revised and expanded.

- On French theater of the period in the provinces and the colonies, see Lauren R. Clay, Stagestruck; The Business of Theater in Eighteenth-Century France and Its Colonies (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013); and Cyril Triolaire, Le Théâtre en province pendant le Consulat et l’Empire (Clermont-Ferrand: Presses universitaires Blaise-Pascal, 2012).

- English translations of police reports and other primary source documents from the period detailing these and similar disturbances can be found in William Driver Howarth, et al. Theatre in Europe: A Documentary History. French Theatre in the Neo-Classical Era, 1550-1789 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

- Copyright restrictions prevent us from reproducing these two images here, but they can be found in Barbara G. Mittman, Spectators on the Stage in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1984), p. 43; and the catalogue from the recent exhibit in Paris entitled La Comédie-Française s’expose au Petit Palais (Paris: Petit Palais Musée des Beaux-Arts de la ville de Paris, 2011), pp. 46-47. Mittman’s book is a good source for other contemporary stage engravings of spectators on the stage. The imagebank section of the CESAR online database also contains engravings, drawings, and other material that will help students envision the seventeenth and eighteenth-century French stage, accessible here.

- The classic treatment of this question is Roger Chartier, “From Court Festivity to City Spectators,” in Forms and Meanings: Texts, Performances, and Audiences From Codex to Computer (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995), pp. 43-82.

- For more on the experience of play-going in eighteenth-century Paris, see Jeffrey S. Ravel, The Contested Parterre: Public Theater and French Political Culture, 1680-1791 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999), pp. 13-66.