Alyssa Goldstein Sepinwall

California State University San Marcos

Making a film about the Holocaust can seem daunting to a twenty-first century filmmaker. In the decades since the camps were liberated, a large number of Holocaust films have already been made. This is especially true in France, where classics from Nuit et brouillard (1955) to Shoah (1985) and Au revoir les enfants (1987) have been seen widely.[1]

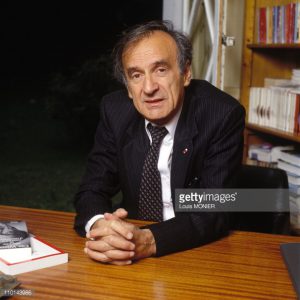

In addition to the size of the canon, the Holocaust presents an additional difficulty for contemporary filmmakers: whether such a horrific event can even be recreated visually. In a 1989 New York Times column, Elie Wiesel denounced the “recent spate of fictionalized accounts” of the Holocaust. He declared: “Auschwitz is … a universe outside the universe, a creation that exists parallel to creation.” Wiesel asked,

Why this determination to show “everything’” in pictures? … How can one “stage” a convoy of uprooted deportees being sent into the unknown, or the liquidation of thousands and thousands of men, women and children? How can one “produce” the machine-gunned, the gassed, the mutilated corpses, when the viewer knows that they are all actors, and that after the filming they will return to the hotel for a well-deserved bath and a meal?

Wiesel argued that direct contact with survivors was the best way to learn about the Holocaust. In its absence, texts by survivors or documentaries showcasing their voices could be acceptable.[2]

Wiesel’s critique of Holocaust dramas underscores how much more difficult it is to represent the Shoah cinematically than other events. However, one thing has changed dramatically since 1989: the possibility of meeting with survivors. In the last five years, their number has dropped precipitously. Those survivors who were teenagers during the Holocaust have reached their early 90s, if they are still living. (Children deported to Auschwitz or other camps were sent to gas chambers immediately, so there are no younger camp survivors). Survivors can thus no longer be the primary transmitters of Holocaust memory.

As survivor ranks have thinned, scholars have become less apprehensive about audiences learning about the Holocaust, at least initially, through film. There have also been challenges to the idea that feature films on the Holocaust are inherently inferior to documentaries and written texts. In his 2005 book Projecting the Holocaust into the Present, Lawrence Baron argued that feature films can sometimes offer “a more tangible sense of how past events were experienced than most academic histories can achieve.” Even when dramas alter historical details, Baron explained, they can still “evoke a sense of the collective and individual choices and historical circumstances” of lived experience during the Holocaust better than non-visual media.[3]

The passage of time has led to shifts in Holocaust education and cinema. In Holocaust testimony, there has been an emphasis on second-generation survivors narrating their parents’ experiences. And in cinema, filmmakers have sought to make the Shoah relevant to audiences who may never meet survivors. Baron has noticed a focus on second-generation themes in newer Holocaust films. In addition, he found that where older viewers “prefer historically realistic movies about the persecution and genocide of Jews during World War II,” those born after 1960 are “more receptive to films that are creative rather than literal” in treating the Holocaust” as well as to films that show “why the Holocaust is relevant today” (p. ix). These tastes, which drive funding for films, have prompted filmmakers to find fresh ways to tackle the topic. Many avoid the problem of restaging by not setting their stories in the camps (at least not for a film’s full length).[4]

French filmmakers have been well-represented among those treating the Holocaust in new ways. I shall focus here on three recent examples: The Origin of Violence, Once in a Lifetime, and Victor “Young” Perez.

L’origine de la violence (2016), directed by Elie Chouraqui and based on a novel by Fabrice Humbert, is one of the newest French films about the Holocaust. Set in the present day, the film raises questions about memory and the legacy of the Shoah. Origin is a thriller, with many twists and turns, as its characters uncover family secrets about the Holocaust. It has parallels with Atom Egoyan’s Remember! (2015), another thriller about Holocaust secrets, as well as with films like Plus Tard (2008) and Sarah’s Key (2010) where secrets about Jewish identity and profiting from the round-up of Jews affect post-war generations.

The Origin of Violence is likely to appeal to history students, since it centers on historical research — while making it look glamorous, with violence and romance along the way. The film’s protagonist is a French teacher, Nathan Fabre. Nathan is writing his history dissertation on German resistance to the Nazis. We see him travelling to Germany to visit Buchenwald/Weimar and to meet a granddaughter of Nazis (Gabi), so that she can provide him with family papers crucial to his research. The film shows Nathan speaking to archivists, checking databases, and finding documents that resolve his puzzles about the past.

However, the film is not only about researching the Holocaust at a distance. While in Buchenwald, Nathan makes a startling discovery, one that launches him on a quest to learn the truth about his own family. He sees a prisoner in a museum photo who looks eerily like his father. Nathan has been raised as a Catholic and a Norman, but he eventually learns that his family has hidden its Ashkenazi heritage, and that the man beyond the barbed wires in the photo, murdered in the camp, was his grandfather.

The film’s central concern is how stories about the past have affected Nathan and his family. The film includes some flashbacks to the 1940s. We meet a Jewish family named the Wagners, including their teenage son David Nathan (Nathan Fabre’s grandfather). The scenes in Paris before the war are lively, full of fashion and color. Once David Wagner has been arrested by Pétain’s police, the flashbacks move to the camps, shot in grey and white. Even in returning to the camps, which have been depicted so many times, Chouraqui is still able to add to our understanding of the experiences of those murdered during the Shoah. Having humanized David before the war, Chouraqui helps the audience experience the intense fear that the young man felt each moment in the camp. He also showcases the moments of dark humor that made existence more tolerable, even fleetingly.

The camp scenes also provoke important questions about the present: to what extent does the trauma that David Wagner experienced carry to the present, to subsequent generations? Chouraqui raises interesting parallels between Wagner’s descendants and those of the Nazis, embodied by Gabi. Other questions that might spark debate in the classroom include: Which is better, remembering or forgetting? Is willful amnesia about history always bad? And were there any circumstances under which collaboration was excusable?

Once in a Lifetime (Les héritiers, 2014) is another recent French film about the Holocaust, set in the present. The film is a paradigmatic example of recent efforts to make the Shoah relevant to diverse French audiences. It has been highlighted as useful for sparking discussions with French collège and lycée students,[5] and it is likely to do so with university students studying French history and culture.

Once in a Lifetime takes place at the Lycée Léon Blum in Créteil. Like the American films Freedom Writers and Dangerous Minds, it celebrates a white-hero teacher who sees the good in children of color whom others dismiss as unteachable. She takes her students seriously, inspires them, and changes their lives. The film is based on a true story, in this case about a teacher named Anne Anglès (called Anne Gueguen in the film to allow for dramatic license). What makes the film unique is that it was co-written by one of Anglès’s former students, who also stars in it. Ahmed Dramé wrote the screenplay with the director Marie-Castille Mention-Schaar, basing it on his own experiences at Lycée Blum. Starring as Malik, a fictionalized version of himself, Dramé was nominated for Meilleur espoir masculin (Rising Star Actor) at the 2015 César Awards.

Once in a Lifetime deals with issues other than the Holocaust. These include conflicts over religion in French public schools. Can a young woman wear a veil to school? Is it against secularism for girls to wear long skirts to school instead of miniskirts à la française? The film also looks at students’ personal challenges as they form their own religious identities; is trying to be “French” betraying their mostly Muslim heritages? The film also fits into the Muslim-Jewish relationship film genre I have chronicled elsewhere, as Malik comes to appreciate his neighbor Mme Levy and to date his Jewish classmate Camélia.[6] Another of the film’s virtues is in humanizing young people in the banlieues who are often dismissed as indifferent and destined for failure. Indeed, Dramé’s memoir is called Nous sommes tous des exceptions (Fayard, 2014); he wants to emphasize that, even though he broke out of his neighborhood and became a success, the others he left behind are also human beings, worthy of concern.

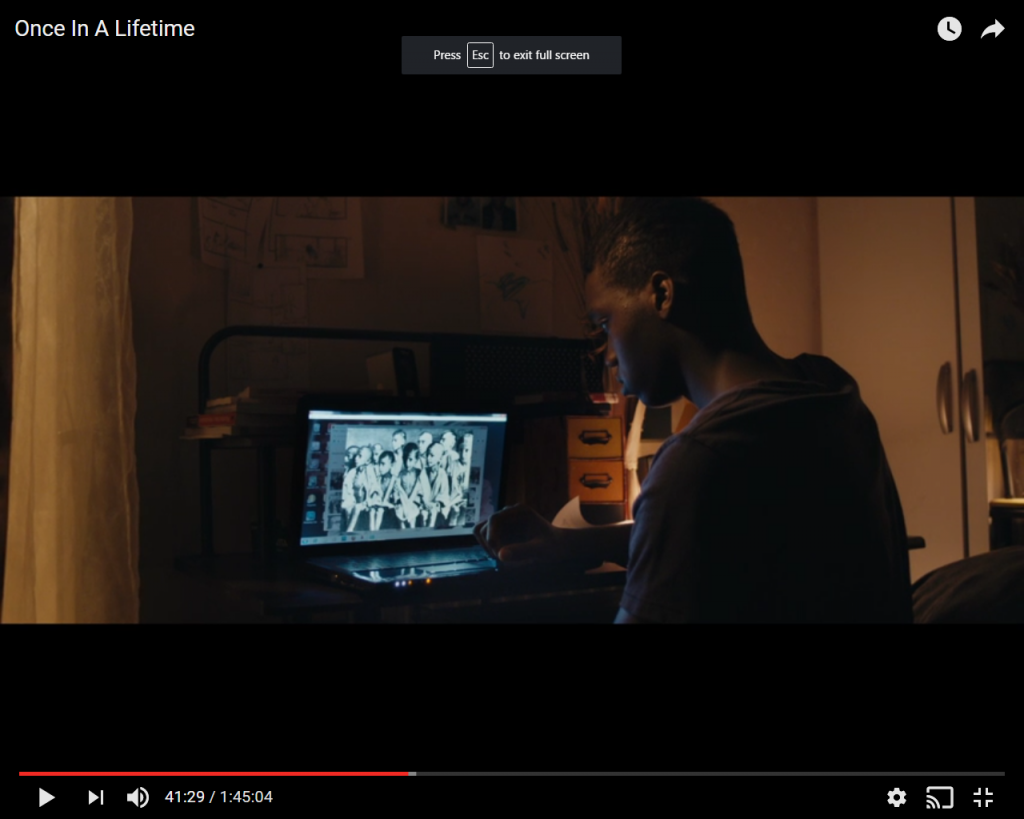

Even while exploring postcolonial issues in France, the film revolves around studying the Holocaust. Mme Gueguen begins the children’s journey from hopelessness to success by encouraging them to enter the French National Contest on Resistance and Deportation. The contest’s annual theme is “Children and Teenagers under the Nazis.” Gueguen is convinced that by helping the teens to learn about racism and religious prejudice beyond their neighborhood, she will be able to awaken both their faith in themselves and their kindness toward those different from them. The students go from thinking, “Jews don’t concern us,” to understanding what it means to target a people for annihilation on the basis of who they are, rather than their actions. The film thus offers a more hopeful view of the potential of young people issus de l’immigration than does the film Entre les murs (The Class, 2008).

Like The Origin of Violence, Once in a Lifetime avoids the pitfalls identified by Wiesel in creative ways. For one thing, though it is fictionalized, it contains a powerful note of realism. French survivor Léon Zyguel appears in the film sharing his testimony with Malik’s class, just as in real life he spoke in Anglès’s class to Ahmed and his friends. When the film was released in fall 2014, Zyguel was alive; however, he died several months later. The film thus preserves a survivor account that might otherwise have been lost. Second, Schaar and Dramé do not recreate camp scenes using actors; rather they insert real primary source images as the students find them in their research. In this way, Dramé and Schaar are able to depict the stark realities of the Shoah (including “muselmann” children, reduced to skin and bones) without having to reenact them. Ultimately, Once in a Lifetime is a powerful testament to seeing each person as an individual with potential, instead of consigning them to stereotypes. Indeed, in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo and HyperCacher attacks in January 2015, the film was seen as a ray of hope for universalism. In February 2015, the Council of Jewish Institutions in France (CRIF) awarded it a special prize.[7]

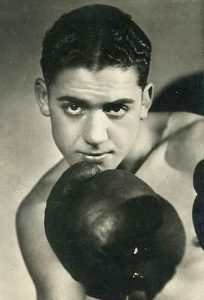

Jacques Ouaniche’s Victor “Young” Perez (2013) shares some features with The Origin of Violence and Once in a Lifetime, while exemplifying still other dimensions of recent Holocaust cinema. The film chronicles the life of a Tunisian Jewish boxing champion, deported to Auschwitz in 1943 and forced to fight for the Nazis’ amusement. Where the other two films deal with memory and the Holocaust’s legacy, Victor “Young” Perez fits a different tendency: the Holocaust explored in its French colonial dimension. Discussions of the Holocaust often assume that victims were Ashkenazi Jews. Karin Albou’s Le chant des mariées (2008), Férid Boughedir’s Villa Jasmin (2008), and Victor Young Perez show that North African Jews (in all three cases, from Tunisia) could also become Holocaust victims. In addition, Victor “Young” Perez fits into the genre of the Holocaust as biopic (which, according to Baron, has become the most prevalent genre of Holocaust film [p. 17]).

While not set in the present, Victor “Young” Perez spans time periods, just like Origin. It moves between colorful scenes set in the nightclubs of 1930s Paris and dimly lit scenes in the camps. The film chronicles the rise of Perez from humble origins in Tunis to the World Flyweight Championship in 1931, before turning to his later deportation. The film’s core resides in its camp scenes. The Nazi commandant of Buna/Monowitz (Auschwitz-III), where Perez has been imprisoned, is offended by the notion that a Jew should have been named world champion in any sport. But he is intrigued by the possibility that his famous prisoner can prove Aryan superiority. He tells Perez that he wants to demonstrate, by staging a match against “real Aryan” opponents, that Perez could only have won the title by buying off the referees. The fact that Perez is emaciated, hungry and terrorized will not be considered in the outcome.

In addition to being a biopic, Victor “Young” Perez falls into another growing genre: the Holocaust sports film. The very idea might seem strange; the genre’s existence has been little discussed in scholarship. However, Victor Young Perez joins at least nine other sports-themed Holocaust films, each intended to draw audiences who might not otherwise want to see a film about the Shoah.[8] These films parallel an effort by museums such as the USHMM and Yad Vashem to use sports as an entry point for engaging students. As Sheryl Ochayon of Yad Vashem has noted, “Using sports in teaching about the Holocaust can be extremely useful …. [It] makes the point that the Holocaust happened in the modern world – a world where there were sports teams, stars and cheering crowds. Sports can be used as a means to bridge the gulf between the Holocaust as a massive historical event and the Holocaust as a human story.”[9] Victor “Young” Perez rests on sports-film staples (will our hero claim victory?) even when presenting them in an uncommon setting. Perez battles to stay on his feet and make the best showing he can for his fellow Jews, no matter how much his Nazi opponent brutalizes him. This dimension of the film offers much to discuss with students, not least of which is the level of agency that concentration camp prisoners had.

While Victor “Young” Perez is powerful in many ways, its least successful scene for me is when Perez embarks in January 1945 on the death march that will claim him as a victim. Films like La Rafle or Sarah’s Key (both from 2010) can resemble reality more easily; in those films depicting the 1942 Vel d’Hiv roundup, the well-nourished actors pretending to be arrested do not look that different from the characters they play, since Jews until that moment had been living free as civilians. However, representing the death march is so challenging that it is almost never shown cinematically, since it requires depicting people who have spent months if not years starving. Ouaniche’s desire to show how Perez suffered is well-intentioned; however, the same actors who were convincing in their boxing scenes (Perez is played by Olympic gold medalist Brahim Asloum) look too strong and healthy to be believable stand-ins for those still alive in the camps after the winter of 1944. The film also collapses some characters from Perez’s real life into composites, though as Robert Rosenstone has noted, this does not disqualify a film from being able to offer important insights into history as lived experience.[10]

All three films make clear that the Holocaust has not been exhausted as cinematic subject matter in France. But recent films differ significantly from older ones which sought to educate viewers about the horrors of the camps and the complicity of French civilians and bureaucrats. These new films seek less to confront audiences with the facts of history than to engage them using contemporary lenses. Whether exploring Holocaust secrets and the legacy of the Shoah, or uncovering North African Jewish victims and unconventional forms of resistance, French filmmakers are finding new ways to make the Holocaust relevant for students and general audiences alike.

Elie Chouraqui, Director, L’origine de la violence [The Origin of Violence], France, Germany, 2016, Color, 116 min, L’Origine Prod, Integral Film, ERF Filmproduktion.

Marie-Castille Mention-Schaar, Director, Les Héritiers [Once in a Lifetime], France, 2014, Color, 105 min, Loma Nasha, Vendredi Film, TFI droits audiovisuels.

Jacques Ouaniche, Director, Victor “Young” Perez, France, Israel, Bulgaria, 2013, Color, 110 min, Noé Productions, Mazel Productions, France 3 Cinéma.

NOTES

- For analysis of these and other classic French films on the Shoah, see André Colombat, The Holocaust in French Film (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1993); Giacomo Lichtner, Film and the Shoah in France and Italy (Portland, OR: Vallentine Mitchell, 2008); Ferzina Banaji, France, Film, and the Holocaust: From le génocide to la shoah (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012); and Alain Kleinberger and Philippe Mesnard, eds., La Shoah: Théâtre et cinéma aux limites de la représentation (Paris: Kimé, 2013).

- Elie Wiesel, “Art and the Holocaust: Trivializing Memory,” New York Times (June 11, 1989), available at http://www.nytimes.com/1989/06/11/movies/art-and-the-holocaust-trivializing-memory.html. See however Wiesel’s apprehension about the weakness of language itself to communicate the horrors of the Holocaust, in Sepinwall, Interview with Elie Wiesel, April 19, 2009, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sXhG7nXHdFc (08:48 – 09:30).

- Lawrence Baron, Projecting the Holocaust into the Present: The Changing Focus of Contemporary Holocaust Cinema (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005), viii – ix. On using film to teach about the Holocaust, see also Anne-Marie Baron, The Shoah on Screen: Representing Crimes against Humanity [trans. of La Shoah à l’écran: crimes contre l’humanité et représentation] (Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, 2006); and Henry Gonshak, Hollywood and the Holocaust (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2015).

- For further analysis of analysis of trends in recent Holocaust cinema, see Oleksandr Kobrynskyy and Gerd Bayer, Holocaust Cinema in the Twenty-First Century: Memory, Images, and the Ethics of Representation (New York: Wallflower Press, 2015).

- See the guide prepared by Collège au cinema/Lycéens et apprentis au cinéma (dossier 223, Les Héritiers), on how to teach using the film, available at http://www.clermont-filmfest.com/03_pole_regional/11_medias/4627_HritiersLesdeMarieCastilleMentionSchaar.pdf

- See Sepinwall, “Reimagining Jewish-Muslim Relations on Screen: French-Jewish Filmmakers and the Middle East Conflict,” in Zvi Jonathan Kaplan and Nadia Malinovich, eds., The Jews of Modern France: Images and Identities (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 302 – 322; and “Jewish-Muslim Romance, With a French Twist: Jean-Jacques Zilbermann’s He’s My Girl,” Fiction and Film for French Historians: A Cultural Bulletin 6, no. 6 (April 2016), at http://h-france.net/fffh/maybe-missed/jewish-muslim-romance-with-a-french-twist-jean-jacques-zilbermanns-hes-my-girl/

- AFP/Le Figaro, “Dîner du Crif: trois prix remis dont un à Bathily,” Le Figaro (23 fév. 2015), at http://www.lefigaro.fr/flash-actu/2015/02/23/97001-20150223FILWWW00074-diner-du-crif-trois-prix-remis-dont-un-a-bathily.php

- Sports-themed Holocaust films include the Hungarian film The Last Goal/Two Half-Times in Hell (1961); the Slovakian film The Boxer and Death (1962); the American film Triumph of the Spirit (1989) about a Greek boxer deported to Auschwitz; István Szabó’s Sunshine (1999), one of whose characters is a Hungarian-Jewish fencing champion; Watermarks (2004), a documentary about Jewish women swimming champions in Vienna in the 1930s; two films about Gretel Bergmann, the German-Jewish high-jumping star who was banned from the 1936 Olympics and later changed her name to Margaret Lambert (Hitler’s Pawn: The Margaret Lambert Story [2004] and Berlin ’36 [2009]); the Macedonian film Third Half (2012); and the German film Landauer – Der Präsident (A Life for Football [2014]). Two other films focus on sports contests in Nazi camps, but without focusing on Jews in particular (Olympics 40 [1981] and Victory [1981]). I am grateful to Lawrence Baron for helping me round out this list by sharing information from his database of Holocaust films; see also his discussion of Triumph of the Spirit as a hybrid sports/Holocaust film (89 – 93).

- Sheryl Ochayon, “Teaching the Holocaust Using Sports,” http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/education/video/hevt_sports.asp. Sports also formed the subject of one of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s earliest exhibitions, on the 1936 Berlin Olympics (online version at https://www.ushmm.org/exhibition/olympics/?content=august_1936&lang=en).

- Rosenstone, History on Film/Film on History (New York: Routledge, 2012), 2nd, 46 – 51.