Issue 2

At its fortieth anniversary, much covered by the international press, 1968 remained “the year that changed everything,” from the Prague Spring to the Chicago riots, by way of a French general strike and the occupation of the Sorbonne. The controversy over its legacy, however, has been bitter in France, focused on the hedonistic abandon of its middle-class participants. The political intrudes occasionally in Louis Malle’s Milou en mai, but, unlike documentaries about the period, it is indeed sexual liberation that permeates the fiction on this period. Does this tell us something worth addressing with our students, or does the phenomenon merely reflect the personal obsessions of the film directors?

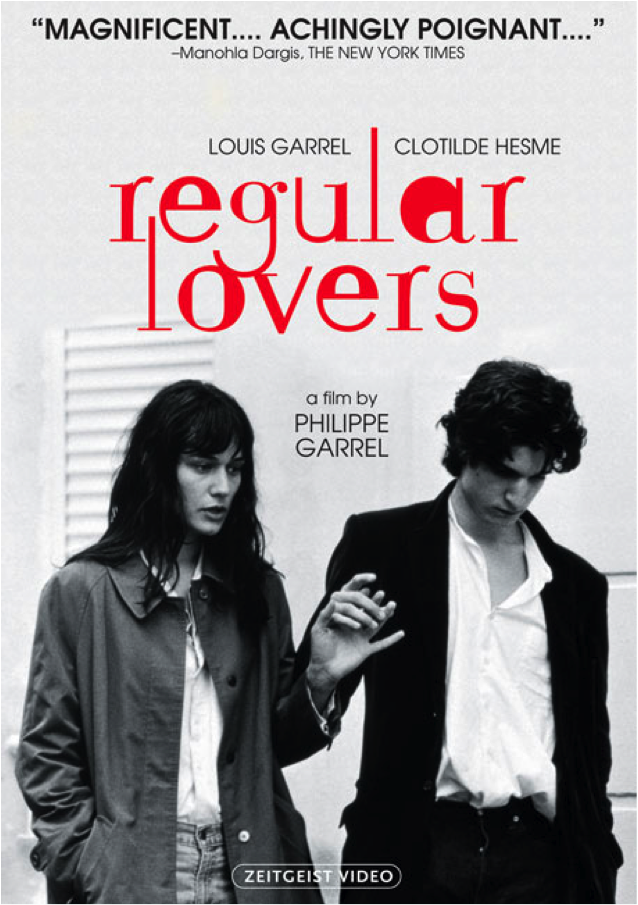

May Fools, The Dreamers & Regular Lovers

Donald M. Reid

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

This time tomorrow, where will we be?

On a spaceship somewhere sailing across an empty sea

–The Kinks (“This Time Tomorrow,” the song to which

soixante-huitards party like it’s 1969 in Regular Lovers)

Did Gustave Flaubert reveal that he was a bourgeois as well as an artist in sharing with George Sand his axiom that “hatred of the bourgeois is the beginning of wisdom”? This anti-bourgeois ethos rooted in the class that dare not speak its name informs the perspective of three of the best known dramatic films set in the era of May 1968: Louis Malle’s May Fools/Milou en mai (1989), Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers (2003), and Philippe Garrel’s Regular Lovers/Les amants réguliers (2004).

Malle’s May Fools opens with a bourgeois matriarch keeling over when she hears about the events of May on the radio. The family gathers for her funeral, but it is held up because the gravediggers are on strike. In a moment when everything seems possible, the family finds liberation from their bourgeois lives in choosing new partners. Liberation takes place not just in the streets of Paris, but also in the family’s unprofitable vineyard, to the sound of Stéphane Grappelli playing L’Internationale. The exploited farmhand digs a grave for the matriarch while the family cavorts. Their free love is interrupted by the specter of a revolution which could threaten their possessions and their persons, so they go off to the forest to hide. Only President Charles de Gaulle’s reassertion of power allows them to escape this sylvan asylum. Most of the avant-mai couples are reunited. However, the one figure who had already repudiated the patriarchal order before May, the lesbian granddaughter, loses her lover to a man.

Malle’s May Fools opens with a bourgeois matriarch keeling over when she hears about the events of May on the radio. The family gathers for her funeral, but it is held up because the gravediggers are on strike. In a moment when everything seems possible, the family finds liberation from their bourgeois lives in choosing new partners. Liberation takes place not just in the streets of Paris, but also in the family’s unprofitable vineyard, to the sound of Stéphane Grappelli playing L’Internationale. The exploited farmhand digs a grave for the matriarch while the family cavorts. Their free love is interrupted by the specter of a revolution which could threaten their possessions and their persons, so they go off to the forest to hide. Only President Charles de Gaulle’s reassertion of power allows them to escape this sylvan asylum. Most of the avant-mai couples are reunited. However, the one figure who had already repudiated the patriarchal order before May, the lesbian granddaughter, loses her lover to a man.

The matriarch’s personal property is divided and arrangements are made to sell the homestead. A local industrialist who had feared that his workers would seize his factory does what capitalists do when order is restored and dumps his factory waste into the farm’s waters. Before May, Milou had resided with his mother and had never been gainfully employed. That is, he lived the life of bucolic freedom that the radical grandson come from Paris for the funeral says his generation is looking for. But there will be no place for this in the new order. Milou’s mistress, the family servant, leaves him to marry a policeman. The family takes its bourgeois héritage to the marketplace. For, after all, to be bourgeois in France has not only meant repudiating on occasion the bourgeois within oneself, it has also meant, when living in the city, invoking one’s rural roots as embodied in country property. The family’s decision to sell the homestead fits with the interpretation Régis Debray offered of May 1968 as an event which resulted in capitalist and bourgeois modernization. Milou, the “back-to-the-land” figure, who, of course, had never left the land, will have no land to which to go back.

In contrast to the rural setting of Malle’s May Fools, both Bertolucci’s The Dreamers and Garrel’s Regular Lovers are set in Paris. The protagonists of The Dreamers are Matthew, a student from a middle-class suburb of San Diego, and Théo and Isabelle, incestuous twins, who draw him into their world.  The twins’ bourgeois parents – the father is a poet who offers the bourgeoisie a frisson of rebellion, but dismisses youthful rebellion in the streets – go to their country house in May, leaving their children in Paris. Matthew had met the twins at the protests over the firing of the director of the Cinémathèque Française, Henri Langlois, in February 1968. If the reinstatement of Langlois can be interpreted as encouraging demonstrations later that spring, the three film buffs in The Dreamers enter the world outside the theater only when their cinematic world is threatened. The three bond when they race through the Louvre mimicking a scene from Godard’s Bande à part. (Bertolucci participates in this game, recreating the demonstration at the Cinémathèque by having the same actors who read Godard’s statement on Langlois’ expulsion in 1968 do so in The Dreamers, thereby reenacting the gestures caught on film thirty-five years earlier.) Théo has a poster of Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise on his wall and treats Mao Zedong as if he were a great cinéaste, plotting the moves of millions of Red Guards. When Théo says that all parents should go to the countryside for re-education, Matthew has to remind him that his parents have already gone there.

The twins’ bourgeois parents – the father is a poet who offers the bourgeoisie a frisson of rebellion, but dismisses youthful rebellion in the streets – go to their country house in May, leaving their children in Paris. Matthew had met the twins at the protests over the firing of the director of the Cinémathèque Française, Henri Langlois, in February 1968. If the reinstatement of Langlois can be interpreted as encouraging demonstrations later that spring, the three film buffs in The Dreamers enter the world outside the theater only when their cinematic world is threatened. The three bond when they race through the Louvre mimicking a scene from Godard’s Bande à part. (Bertolucci participates in this game, recreating the demonstration at the Cinémathèque by having the same actors who read Godard’s statement on Langlois’ expulsion in 1968 do so in The Dreamers, thereby reenacting the gestures caught on film thirty-five years earlier.) Théo has a poster of Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise on his wall and treats Mao Zedong as if he were a great cinéaste, plotting the moves of millions of Red Guards. When Théo says that all parents should go to the countryside for re-education, Matthew has to remind him that his parents have already gone there.

Accidental revelation of the twins’ incestuous relationship (when the parents visit the spacious Paris apartment to drop off a check for their children) and the American Matthew’s introduction of the external world in the form of “asking out” Isabelle, threaten the twins’ insular world. Isabelle’s initial response to her parents’ discovery of her relationship to Théo is suicide, but this is fortuitously interrupted by a street demonstration. The three join in, but when Théo throws a Molotov cocktail at the police, the pacifist Matthew (who had earlier told Théo that Mao’s actors were “extras”) is left behind. Thus, the demonstrations of May 1968 temporarily save the bourgeois youths, whose love is a repudiation of bourgeois norms, from the dual threats of bourgeois normalization and American culture.

Philippe Garrel’s Regular Lovers is a dialogue with The Dreamers. François, the star of Regular Lovers, is played by the director’s son, Louis Garrel, who had also played Théo in The Dreamers. In their press conference at the Venice film festival, where Regular Lovers won the Silver Lion in 2005,  Philippe Garrel explained that he had taken advantage of the costumes available from The Dreamers, and Louis Garrel said that the same actors were used as policemen in both films. In the second film, a bourgeois poet named François falls in love with Lillie, a sculptress, to whom he is not related and who is from a different social class, which may make them regular lovers. Lillie tells us that she has seen Bertolucci’s Before the Revolution, the story of Fabrizio, the bourgeois who comes to despise socialist culture, rejects the party and embraces a bourgeois life. Lillie is the daughter of a Communist factory worker and immigrant from Italy who had forsaken art for his family. Her 1968 will take the form of not making this sacrifice and she eventually abandons François to pursue her career in the United States. Though gauchiste friends of François tell him that things are happening politically, no manif will stop him from committing suicide that night.

Philippe Garrel explained that he had taken advantage of the costumes available from The Dreamers, and Louis Garrel said that the same actors were used as policemen in both films. In the second film, a bourgeois poet named François falls in love with Lillie, a sculptress, to whom he is not related and who is from a different social class, which may make them regular lovers. Lillie tells us that she has seen Bertolucci’s Before the Revolution, the story of Fabrizio, the bourgeois who comes to despise socialist culture, rejects the party and embraces a bourgeois life. Lillie is the daughter of a Communist factory worker and immigrant from Italy who had forsaken art for his family. Her 1968 will take the form of not making this sacrifice and she eventually abandons François to pursue her career in the United States. Though gauchiste friends of François tell him that things are happening politically, no manif will stop him from committing suicide that night.

Regular Lovers begins before May with François as an insoumis (draft-dodger). His lawyer gets François a suspended sentence with the anti-bourgeois bourgeois defense, which only a bourgeois artist could avail himself of, that protecting his poetic genius from the drudgery of the caserne will be of greater value to France than his military service. Hash and opium figure from the start. It is not an accident that smoking on the barricades precedes the scene in which the street-fighting students become the rebels of 1789 or 1848. Like a good bourgeois, François calls on his rural roots, which in his imagination take the form of an armed peasant uprising.

Unlike The Dreamers and May Fools, Regular Lovers does not end with the demonstrations of May 1968, but follows François, Lillie, and their world into l’après-mai. Until May 1968, François and his friends lived with their bourgeois parents. Escaping from the police, François shows up at what might be the apartment of his father’s mistress; she draws him a bath and gives him his father’s clothes to wear. When a demonstrator returns to find his mother vacuuming, she sends him to bed and picks his dirty boots off the floor. After May 1968, François and Lillie attach themselves to a group funded by Antoine, a young bourgeois who says the revolution happened for him when his father died and the wealth he inherited allowed him to create a world without laws. He buys dope and serves as a patron of the arts for his community. The beginning of the end comes when Antoine and his entourage move to Morocco, leaving François behind.

All three films share a sense that the most radical events of May 1968 did not take place in the streets of Paris, but in bourgeois vineyards, Paris apartments or the history-saturated imaginations of those who threw the pavés. These acts were born of the contradictory elements in bourgeois culture. May 1968 concludes with the restoration of bourgeois order. Milou will lose the shelter from the market the family estate had provided; the twins, though saved by May 1968, will have to confront their parents, whose time in the countryside did not include re-education in polymorphous perversity; François won’t find a niche as a bourgeois poet, like that occupied by Théo’s father in The Dreamers. Lillie can become a successful artist and a self-proclaimed anarchist only by moving to America, the country that, as François Furet reminds us, has no bourgeoisie. Each of these films evokes May 1968 not so much as a revolution lost, but as elements of the anti-bourgeois bourgeois world mired in painfully sentimental educations.

As historians of memory of the Occupation know, films are both important historical sources and excellent classroom materials for students to analyze. For the memory of May 1968, May Fools has the most to offer in the classroom. Louis Malle had apparently been thinking about Jean Renoir while making this film, and it would work well in a course on modern French history, especially when shown in conjunction with Renoir’s La Règle du jeu. There is some nudity in May Fools, but the full frontal nudity in Bertolucci’s The Dreamers makes it even trickier to show in class. That Bertolucci is Italian and the screenwriter Gilbert Adair is English also situates The Dreamers as a European, rather than solely French, reflection on May 1968. However, May 1968 is clearly important within the collective memory of an entire generation of Europeans. Students could also read Adair’s short novel The Holy Innocents (1988) on which The Dreamers is based. (The French version of the film is, in fact, called Les Innocents). In the novel, Matthew is (accidentally?) shot to death by the police. Why the change in Matthew’s fate between the book and the film and what this could reveal are potentially interesting questions for a class to discuss. Regular Lovers, a three-hour, black-and-white film (with no nudity!), will try the patience of most American college students today. However, if they are prepared to read the film as a novella about navigating the complexities and false starts that characterize any venture on “a spaceship somewhere sailing across an empty sea,” they will find themselves exploring the relation between the memory of youth and the memory of a particular historical situation, and aware that juxtaposition of the two turns the past into a foreign country to which they, the viewers living “this time tomorrow,” have gained a passport.

Louis Malle, Director, Milou en Mai [May Fools] (1990), France and Italy/Color, Nouvelles Editions de Films/TF1 Films/Ellepi Films Production/released by Orion Classics. Running Time: 107 min.

Bernardo Bertolucci, Director, The Dreamers (2003), Italy/Color, Recorded Pictures Company/Peninsula Films/Fiction Films. Running Time (R-rated version): 112 min.

Philippe Garrel, Director, Les amants réguliers [Regular Lovers] (2005), France/Black and White, Maia Films/Arte/France Cinéma/ Programme Media de la Communauté européenne. Running Time: 183 min.