Issue 3

Somewhat surprisingly, no films deal directly with the Haitian Revolution – although a biopic on Toussaint Louverture is in the works. All the same Burn! transparently alludes to it, and Les caprices d’un fleuve, set in a slave-trading port in Africa, potently displays French racial prejudices in the age of the French Revolution. Neither film is new, and they would surely be markedly different if made today. But that is why showing an historical film – in both senses of the adjective – can be so helpful to students. In an old cliché, the context becomes the text. The time and place in which the story takes place is doubled by the time and place in which the film was made. And as our reviewer points out, showing such movies alongside ones of a similar genre creates a third layer of contextualization. Pretty soon nothing is just black and white – not the characters, not the prejudices, not even the older films themselves.

Les caprices d’un fleuve and Burn!

Alyssa Goldstein Sepinwall

California State University, San Marcos

The best films on colonial encounters humanize the participants, whether colonizers or colonized. They help students understand multiple perspectives; they undermine assumptions about the passivity and backwardness of colonized peoples. Moreover, film helps students understand colonialism as a lived experience – one that affects individuals differently and that can transform colonizers as profoundly as the colonized. Certainly, not all films on empire are of equal quality. Nevertheless, even “bad films” that Orientalize colonized peoples can be useful in the classroom. Not only can they help students enter the mindset of colonizers, they can prompt questions about colonial memory. Why are certain films made today? How do they reflect colonialist thinking, then and now?

Historians teaching about the nineteenth – and twentieth – century empires can choose from a wide array of modern films, as well as others made at the height of empire, whether documentaries or fictions.[1] However, for the first French empire, choices are few. Black Robe (1991, dir. Bruce Beresford) is a wonderfully complex film which can be used to teach about contact between Europeans and First Peoples in Canada, especially when combined with the Jesuit Relations. An analogous film for the French Caribbean does not exist. Nevertheless, two films can be used – with care – in courses covering French slavery or the Haitian Revolution: Les caprices d’un fleuve (1996) and Burn! (Queimada, 1969). Neither is ideal, and neither portrays the motivations and humanity of the colonized as fully as that of colonizers. Of the two, Burn! is both more complex and easier to use in the classroom (its dialogue is largely in English, whereas Les caprices is not available with subtitles). Still, the imperfections of each film promise many teachable moments.

Les caprices d’un fleuve was directed by Bernard Giraudeau, who also plays the film’s central character, Jean-François de la Plaine. The story begins in 1785, when Louis XVI banishes Jean-François to a French outpost in West Africa after the latter has killed one of the king’s favorites in a duel. Jean-François leaves behind his lover, Louise de Saint-Agnan, and a life full of culture and opulence. The film then moves to the dusty comptoir of Cap Saint-Louis (modern Senegal), where the exiled Jean-François will serve as governor. Early scenes show him disdaining the backward natives and the triviality of his post, while pining for Louise and the musical salons they enjoyed together. Over the course of the film, Jean-François’s attraction to two women transforms him. First, he has a torrid affair with Anne Brisseau, a wealthy mixed-race (signare) slave trader. Later, he falls in love with one of his slaves, Amélie, whom he had earlier seen as his adopted daughter and tried to turn into a proper French girl, Eliza Doolittle-style. Amélie and Jean-François eventually have a child together, but she dies in childbirth. After having been recalled to France by the Convention, Jean-François returns to Africa to raise his child. Overall, the film’s Europeans fall into two categories: “bad European” slave traders who make racist comments and “good Europeans” who embrace métissage, particularly by becoming involved with African women.

Les caprices d’un fleuve was directed by Bernard Giraudeau, who also plays the film’s central character, Jean-François de la Plaine. The story begins in 1785, when Louis XVI banishes Jean-François to a French outpost in West Africa after the latter has killed one of the king’s favorites in a duel. Jean-François leaves behind his lover, Louise de Saint-Agnan, and a life full of culture and opulence. The film then moves to the dusty comptoir of Cap Saint-Louis (modern Senegal), where the exiled Jean-François will serve as governor. Early scenes show him disdaining the backward natives and the triviality of his post, while pining for Louise and the musical salons they enjoyed together. Over the course of the film, Jean-François’s attraction to two women transforms him. First, he has a torrid affair with Anne Brisseau, a wealthy mixed-race (signare) slave trader. Later, he falls in love with one of his slaves, Amélie, whom he had earlier seen as his adopted daughter and tried to turn into a proper French girl, Eliza Doolittle-style. Amélie and Jean-François eventually have a child together, but she dies in childbirth. After having been recalled to France by the Convention, Jean-François returns to Africa to raise his child. Overall, the film’s Europeans fall into two categories: “bad European” slave traders who make racist comments and “good Europeans” who embrace métissage, particularly by becoming involved with African women.

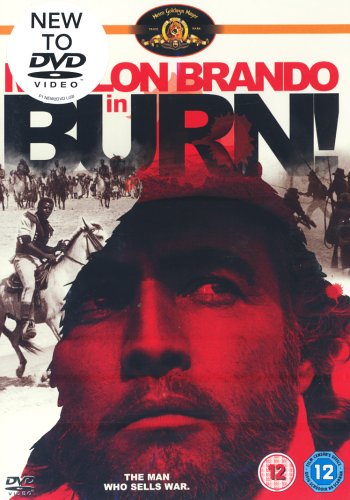

Burn!, directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, is set in the fictional Portuguese colony of Queimada in the 1840s; it is primarily modeled on the Haitian Revolution. Marlon Brando plays Sir William Walker, a British adventurer who foments a rebellion so that Britain can capture Queimada’s sugar trade. He produces a leader who resembles Toussaint Louverture in Jose Dolores (Evaristo Márquez), a dock porter whom Walker tricks into launching a rebellion. Simultaneously, Walker persuades Creole plantation owners to assassinate the island’s Portuguese governor so that they can rule themselves. After slavery is abolished and the overseas Portuguese ejected, Walker tries to manipulate Dolores into laying down his arms and accepting Creole rule. “Who will govern your island, Jose?” he asks. “Who will run your industries? … Civilization is not a simple matter, Jose. You cannot learn its secrets overnight.” Dolores later leads a revolt against the island’s new rulers, but is captured and executed. As Walker prepares to leave the island, he too is killed, stabbed by a dock porter.

In many ways, Burn! is a useful dramatization of slave resistance. It criticizes colonial exploitation; the duplicitous William Walker is shown as deserving his fate. Students enjoy Burn!, since it is structured as an adventure and much of the dialogue is in English. However, the film is not as successful as Pontecorvo’s Battle of Algiers (1966) in showing the agency of colonized peoples. Though Walker is manipulative, the African population appears as easy marks; moreover, he provides both the ideas and strategy for the slave revolt. Dolores is virtually the only African in the film whom the viewer gets to know, while other slaves remain exoticized masses. The film’s portrayal of mixed-race women as prostitutes is also problematic.[2] Nevertheless, Burn! can easily become an integral part of a unit on the Haitian Revolution if it is handled appropriately. The film is best taught alongside Carolyn Fick’s The Making of Haiti, which treats the Haitian Revolution from below and gives more accurate detail about slave life and resistance.[3]

In many ways, Burn! is a useful dramatization of slave resistance. It criticizes colonial exploitation; the duplicitous William Walker is shown as deserving his fate. Students enjoy Burn!, since it is structured as an adventure and much of the dialogue is in English. However, the film is not as successful as Pontecorvo’s Battle of Algiers (1966) in showing the agency of colonized peoples. Though Walker is manipulative, the African population appears as easy marks; moreover, he provides both the ideas and strategy for the slave revolt. Dolores is virtually the only African in the film whom the viewer gets to know, while other slaves remain exoticized masses. The film’s portrayal of mixed-race women as prostitutes is also problematic.[2] Nevertheless, Burn! can easily become an integral part of a unit on the Haitian Revolution if it is handled appropriately. The film is best taught alongside Carolyn Fick’s The Making of Haiti, which treats the Haitian Revolution from below and gives more accurate detail about slave life and resistance.[3]

Using Les caprices d’un fleuve in the classroom is more complicated. On the one hand, the film (with its depictions of West African kings and armies) undermines students’ assumptions about the relative power of Europeans and Africans in the eighteenth century. It humanizes some Africans by showing how alluring Anne and Amélie turn out to be once Jean-François abandons his initial prejudices. Moreover, the film contains some affecting depictions of slavery and the slave trade. As Christopher Miller has pointed out, mainstream French films have been almost entirely silent on the subject of slavery.[4] Consequently, that the film discussed the topic at all was noteworthy to many French critics. Le Monde de l’Éducation said Les caprices could “remind young generations of one of the greatest crimes against humanity.” L’Humanité Dimanche praised the film’s “courageous” antiracist message and French high school students were encouraged to see the film as part of the Lycéens au cinéma program.[5]

On the other hand, as the Anglophone criticism of the film has suggested, Les caprices cannot be read as unambiguously anti-colonial. The film is shot through European eyes, with a foreign gaze scrutinizing an exoticized landscape and strange-seeming customs (it differs here from the superb Rue Cases-Nègres [Sugar Cane Alley, 1983, dir. Euzhan Palcy], which offers the history-from-below perspective of twentieth-century Caribbean sugar-cane cutters). Moreover, though Les caprices is meant as a paean to anti-racism, with dutiful references to Enlightenment abolitionism, it is permeated by unwitting colonialist thinking. As John Emerson has pointed out, the film reinforces ideas of Europe as old and cultured and Africa as new and in need of tutelage. Aside from Anne and Amélie, Emerson notes, we learn nothing of other Africans’ personal lives or private feelings. In addition, Africans in the film seem to be “begging Europe to rescue them.” More fundamentally, Emerson argues, the film “depicts African culture as a civilisation in tatters, thus justifying its subsequent colonization. … it reinforces the argument offered by Francis Ramirez that France prefers to believe that it conquered its colonised peoples by seduction rather than force.”[6]

Other reviewers have pointed to similar flaws. Variety noted “that the other slaves [beyond Amélie] seem to be an afterthought (or no thought) both to Jean-Francois and the film points up the problems with a movie that says one thing but shows another,” adding that “despite Jean-Francois’ abolitionist lip service, the exceedingly complex and troubling dynamics of an intimate relationship between an adult white man and an adolescent black girl (master and slave, no less) goes largely unexplored. And while the film’s dialogue exalts the virtues of its female characters, the women themselves remain ciphers, one-dimensional fantasies.” Carrie Tarr, one of the best critics of colonial film, termed Les caprices a “neo-colonial action film.” In her view, “although it includes debates about slavery and human rights, its focalization through the point of view of its dashing, music-loving exiled governor … works conventionally to repossess the colonial landscape and people.” Christopher Miller pithily described Les caprices as “a strange, narcissistic film that nonetheless contains some striking images of the slave trade.”[7]

Two scenes typify how the film purports to celebrate human universality yet at the same time reifies human difference; indeed, one character is set to write an “éloge de la différence” but dies before completing it. In the first scene, Jean-François declares that Anne makes love differently than Louise because she is a “Negress.” In a later scene, Jean-François is disturbed by Amélie’s putting on a European dress in imitation of a white lady’s portrait, adding that she is African and should stay that way.[8] The film’s press dossier reinforces the notion of African difference by proclaiming that only Giraudeau, a man with a “passion for African sensuality, smells, music and women,” could have made this film.[9]

Thus, despite some heartfelt denunciations of racism in Les caprices, the film critiques fantasies of integration in a surprisingly old-fashioned way. It comes nearly to the same conclusion as Princesse Tam-Tam (dir. Edmond Gréville), made in 1935! In that film, a dashing, cultured Frenchman tries to transform a barefoot Tunisian (played by Josephine Baker) into a cultured “princess”; he eventually falls in love with her. However, as the film ends, we learn that this was but a chimera, since Baker’s character can never be civilized. As in that film, Les caprices implies that the effort to civilize non-Europeans is useless. As a French colleague says to Jean-François, “Vous partirez, elle restera. Que serait-elle devenue à réciter des vers dans les sables du désert ? [You will leave, she will stay. What will become of her reciting poetry amidst the desert sands?]”[10]

Despite these flaws – or perhaps, because of them – Les caprices can still be valuable in the classroom. For one thing, in its ambivalent treatment of Africans (decrying their enslavement while depicting them as Other), it mirrors certain Enlightenment views. Moreover, though the lack of subtitles makes it difficult to show in its entirety to Anglophones (in truth, its slow pace may not appeal to many students anyway), certain vivid clips can still be used. These include a scene of Jean-François’s party hesitantly paying a visit to an African king (mins. 34:30-37:30); another depicting a battle between Jean-François’s men and a group of African slave traders as he tries to rescue Amélie, who has run away out of jealousy over his affair with Anne (1:21:20-1:23:00); and another showing a slave trader inspecting a pen of teenage slaves, while poking their body parts (1:10:50-1:11:35).

For students who can understand French and thus watch the whole film, Les caprices can also be compared to other movies with slavery and colonial themes. For instance, the self-evident idea that Amélie should desire her heroic European slave-owner can be contrasted with Chocolat (1988, dir. Claire Denis). In that film, the African servant Protée suffers daily humiliations at the hands of his “benevolent” European employers; he rejects his mistress’s efforts to seduce him. The film can also be contrasted with representations of slavery in American and African films. One easily accessible film to watch alongside Les caprices is Amistad (1997, dir. Steven Spielberg); the latter has far more brutal images of slavery even if it also centers on a heroic white figure. Instructors can also contrast Les caprices (or Burn!) with Ceddo (1979, dir. Ousmane Sembene), Sankofa (1993, dir. Haile Gerima) and Middle Passage (2000, dir. Guy Deslauriers), all of which offer African or Antillais perspectives on the slave trade.[11] The relative benignity of Les caprices (Variety called it “one of the most tranquil movies ever made about slave trading”) can also be used to highlight differences in American and French memories of slavery and colonialism. That French reviewers praised Les caprices just for portraying slavery – and were not troubled by Giraudeau’s portrayal of a master-slave romance, since he was championing métissage in an era when the Front National opposed it – can also be discussed in the classroom.[12]

A final comparison can be made with Indochine (1992, dir. Régis Warner). Both Les caprices and Indochine are ostensibly anti-colonial, yet they also feature much colonial nostalgia. Both are told from the perspective of sympathetic colonizers, and both feature an ill-fated interracial romance. Each film also shows a certain ambivalence about colonial independence: in both Indochine and Les caprices, the son produced by this romance is raised by his European parent or grandparent, after his Vietnamese/African mother is unable to take care of him.

As I have tried to show, neither Les caprices d’un fleuve nor Burn! should be used alone to teach about slavery and slave resistance; both films have problematic aspects. Nevertheless, they each can be used very successfully in the classroom if presented in conjunction with well-chosen scholarship and probing questions. They can help to teach both the complexities of early modern empire and the caprices of colonial memory.

- For a good discussion of films on the modern French empire, see Alison Murray, “Teaching Colonial History through Film,” French Historical Studies 25 (2002): 41-52; see also my discussion in Alyssa Goldstein Sepinwall, “‘Is This Tocqueville or George W. Bush?’ Teaching French Colonialism in Southern California After 9/11,” World History Bulletin 26 (2010), 18-23. On documentaries, see Peter J. Bloom, French Colonial Documentary: Mythologies of Humanitarianism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), which includes a list of colonial documentaries on pp. 208-15.

- For more, see Sepinwall, “Burn!” in Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellions, ed. Junius P. Rodriguez (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2006), 1: 86-88; and Natalie Zemon Davis, Slaves on Screen: Film and Historical Vision (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2000), ch. 3.

- Carolyn E. Fick, The Making of Haiti : The Saint Domingue Revolution from Below (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1990), esp. chs. 1 and 2.

- See Christopher L. Miller, The French Atlantic Triangle: Literature and Culture of the Slave Trade (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 376.

- See these and other review excerpts in Avant-scène cinema, no. 462 (May 1997), 77-82.

- http://www.bifi.fr/upload/bibliotheque/File/Lyc%C3%A9ens%20au%20cin%C3%A9ma%20PDF/caprices.pdf has a useful teaching guide. See John Emerson, “Capricious Resolution in Postcolonial Filmic Narratives,” in Endings [Dialogues 2], ed. Ann Amherst, Katherine Astbury et al. (Exeter: Elm Bank, 1999), 51-56; and idem, “The Representation of the Colonial Past in French and Australian Cinema, from 1970 to 2000” (Ph.D. diss., University of Adelaide, 2003).

- See Greg Evans, review of Les caprices d’un fleuve, in Variety, Dec. 4, 1995: http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117910522.html?categoryid=31&cs=1 (accessed October 5, 2010); Carrie Tarr, “French Cinema and Postcolonial Minorities,” in Post-Colonial Cultures in France, Alec G. Hargreaves and Mark McKinney, eds. (New York: Routledge, 1997), 65; and Miller, The French Atlantic Triangle, 522.

- See script of the film published in Avant-scène cinema, no. 462 (May 1997), 9 – 75 (relevant scenes at 49, 68).

- See Lycéens au cinéma guide (n. 9 above), 6.

- Avant-scène cinema, no. 462 (May 1997), 59.

- For more on these films, see Robert Harms, “The Transatlantic Slave Trade in Cinema,” in Black and White in Colour: African History on Screen, Vivian Bickford-Smith and Richard Mendelsohn, eds. (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2007), 59-81; and Miller, The French Atlantic Triangle, 370-73, 376-77.

- For a fuller comparison of American and French memory on slavery, see Sepinwall, “The Specter of Saint-Domingue: American and French Reactions to the Haitian Revolution,” in The World of the Haitian Revolution, eds. Norman Fiering and David Geggus (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009), 317-38 (esp. 323-25).

Bernard Giraudeau, Director, Les Caprices d’un fleuve (1996) France/Color, Canal+/Flach Film/Les Films de la Saga. Running Time: 111 min.

Gillo Pontecorvo, Director, Queimada [Burn!] (1969) France and Italy/Color, Europee Associate SAS/Produzioni Europee Associati (PEA)/released by Criterion Collection. Running Time (USA dubbed): 112 min.