Charlotte C. Wells

University of Northern Iowa

First, a disclaimer: the author of this review is not a film or literature specialist. All you’ve got is an early modern historian who teaches a lot more survey courses and a lot less specialty than would be the case in the best of all possible worlds. So when challenged to take on The Three Musketeers in its cinematic incarnations, I wondered whether any of them could be used in the classroom to spark discussion about early modern France. For that reason I chose to stick with films in English and films set in the seventeenth century. No Musketeers in the French Foreign Legion, no singing Musketeers, no cartoon or superhero Musketeers, though such versions abound, and some of them are fun.

To begin, a little background: there were seventeenth-century musketeers, both in France and elsewhere. They were generally elite infantry, whose weapons had longer range and greater stopping power than the older arquebus. In France, Louis XIII created a unit of mounted musketeers as part of his household troops in 1622. Cardinal Richelieu followed with his own company of musketeers, which eventually passed to Cardinal Mazarin. The two companies competed, though probably not as vigorously as in Dumas’ fiction. They merged into one after Mazarin’s death in 1661. A certain d’Artagnan commanded this combined troop under Louis XIV.

For there was a real d’Artagnan. Dumas took much of his story from the mostly fictional Mémoires de M. d’Artagnan, published by hack author Gatien de Courtilz de Sandras in 1700. But Courtilz might have gleaned memories of the actual d’Artagnan during his imprisonment in the Bastille from 1693-1699. Its governor, Besmaux, had been a friend of the doughty captain of Musketeers, Charles Ogier Batz de Castelmore, Comte d’Artagnan, born in Lupiac in Gascony in 1611 and killed at the siege of Maastricht in 1673. Rather than working against the machinations of Cardinal Richelieu, he was an agent for Cardinal Mazarin and used the cardinal’s patronage as a springboard to serving Louis XIV. For the Sun King, d’Artagnan did everything from arresting Fouquet to serving as governor of Lille before his much-lamented death in battle. He’d achieved upward mobility, seventeenth-century style. Athos, Porthos and Aramis? Also real, probably friends and colleagues of d’Artagnan, although their relations are difficult to clarify from the historical record.[1]

For there was a real d’Artagnan. Dumas took much of his story from the mostly fictional Mémoires de M. d’Artagnan, published by hack author Gatien de Courtilz de Sandras in 1700. But Courtilz might have gleaned memories of the actual d’Artagnan during his imprisonment in the Bastille from 1693-1699. Its governor, Besmaux, had been a friend of the doughty captain of Musketeers, Charles Ogier Batz de Castelmore, Comte d’Artagnan, born in Lupiac in Gascony in 1611 and killed at the siege of Maastricht in 1673. Rather than working against the machinations of Cardinal Richelieu, he was an agent for Cardinal Mazarin and used the cardinal’s patronage as a springboard to serving Louis XIV. For the Sun King, d’Artagnan did everything from arresting Fouquet to serving as governor of Lille before his much-lamented death in battle. He’d achieved upward mobility, seventeenth-century style. Athos, Porthos and Aramis? Also real, probably friends and colleagues of d’Artagnan, although their relations are difficult to clarify from the historical record.[1]

The real d’Artagnan lived in a world of violence, both political and personal. In politics, wars both civil and foreign offered opportunities for young men with military skills. The same could be said of the more personal violence of civil society. The Bourbon monarchy sought to control the chaos, but with limited success before Louis XIV. Dumas managed to capture the desire for order and the reality of chaos that characterized France in the early seventeenth century. It is another question whether any of the cinematic versions of his work does the same. As a recent FFFH reviewer noted, films and novels tell the same story in very different ways.[2]

There have been over one hundred film adaptations of The Three Musketeers, a number impossible to cover in an essay of this length.[3] We’ll focus on five: the silent 1921 version starring Douglas Fairbanks as d’Artagnan, the 1948 production with Gene Kelly as d’Artagnan and Vincent Price as Richelieu, the 1970s Richard Lester films with Michael York as the hero and Charlton Heston as the Cardinal, and the current BBC America series with Luke Pasqualino as d’Artagnan and a now-departed Peter Capaldi as Richelieu.

Douglas Fairbanks settled on The Three Musketeers as one of the first productions for United Artists Studio, which he co-founded with Mary Pickford and D.W. Griffith. Fairbanks was turning from his earlier romantic comedies to the swashbuckling epics of his peak career. The Three Musketeers was a logical choice and the film is memorable, although the Fairbanks version might better be titled D’Artagnan and Friends, since it focuses on the star. The musketeers, played by Léon Bary, George Siegmann, and Eugene Pallette, seem mostly a backdrop for Fairbanks, as does Marguerite de la Motte as Constance. Mary Maclaren emotes enthusiastically as Anne of Austria and Adolphe Menjou achieves some dignity as Louis XIII, but only Nigel de Brulier as Richelieu competes with the star. The flexing fingers on his chair arm betray his tension as he awaits the results of his machinations—no words necessary. Nor are they needed to appreciate Fairbanks’ hilarious portrayal of d’Artagnan as a young man given to large gestures. The scene where, newly arrived in Paris, he exchanges his horse for a hat more suitable to his new life is not in the original novel, but it should have been. Likewise the one in which he uses a guard’s shoulder to vault over the gate to the port at Calais.

But so much of the story has been cut away or modified for social acceptability—Constance is the grandchild of M. Bonancieux and remains alive to marry d’Artagnan for the required happy ending–the film isn’t really Dumas at all, and it certainly isn’t history. The tidy streets where d’Artagnan swaggers are a dead give-away. Yet it was influential: viewing Musketeer films in sequence shows that Fairbanks set the pattern for all interpretations of the story until its present BBC incarnation. The 1948 Three Musketeers simply took what Fairbanks had done and did it better.

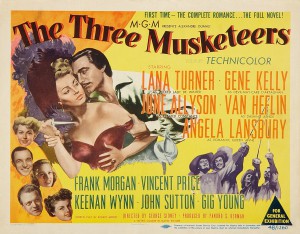

That film, released by Metro Goldwyn-Mayer, has dazzling fights, more so than any of the films examined here. Gene Kelly leaps over statues, swings through windows, and duels from perches with a kind of blazing joy that seems to echo duelists’ love affair with death. This version also features Vincent Price as a wonderfully urbane Richelieu, who has a decidedly unhistorical ambition to make himself king, and Lana Turner as a deliciously evil Milady. When the two get together to plot, they positively ooze devilish delight. The film is worth watching for them alone.

But again, it’s neither history nor an accurate retelling of the novel. While following Dumas through the initial scenes and the general plot of Queen Anne’s romance with the Duke of Buckingham and the diamond studs affair, it begins to go its own way with the presentation of Constance, played by June Allyson, as the goddaughter of M. Bonancieux, on-screen adultery not being acceptable in 1948 any more than it was in 1921. She and d’Artagnan fall in love at first sight, although the romance is spoiled by d’Artagnan’s fascination with Milady; in one of the film’s more hilarious scenes he attempts to seduce her while masquerading as M. de Warennes. Once he has recovered, he and Constance pass an apparently chaste—but blissful—wedding night before she is sent to safety by the queen. Safety means staying with the Duke of Buckingham! In England Constance becomes the captured Milady’s jailor, Buckingham reasoning that a woman should be safe from her seductions. The duke is mistaken: Milady gets Constance to slip her a knife by pretending she seeks honorable suicide. Instead she murders both Constance and the Duke, and the Musketeers arrive too late. They are not too late to pursue Milady to her French hideout, where she is duly put to death. As in the original, d’Artagnan and the others escape punishment by producing the carte blanche Richelieu had given Milady. The king rewards them according to their desires, and all ends happily.

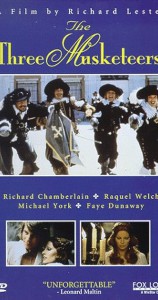

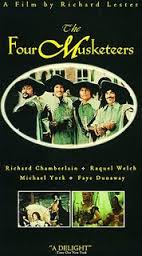

Richard Lester achieved something more with the Musketeer movies he directed between 1973 and 1989. The first two, The Three Musketeers and The Four Musketeers (released in 1973 and 1974), were made as a single film, only to have the producers, Alexander and Ilya Salkind, realize that the result was too long for one theatrical release. They turned one film into two, giving rise to much irritation and several lawsuits on the part of the cast and crew, who had been paid only for one. The reason for the length is that the Lester films are the only ones that completely cover Dumas’ tale. An incandescent d’Artagnan kills Rochefort before an audience of horrified nuns after Milady has murdered Constance. Milady is captured, judged by the four and hanged by her husband.

Lester had originally intended the Beatles (whom he directed in A Hard Day’s Night and Help) to play the Musketeers. Probably fortunate that the lads from Liverpool were replaced by Oliver Reed (Athos), Richard Chamberlain (Aramis), Frank Finlay (Porthos), and Michael York, who embodies the exuberant d’Artagnan with a gangling enthusiasm that almost matches Kelly’s brilliance. They are joined by Raquel Welch as Constance Bonancieux, Faye Dunaway as Milady, Christopher Lee as Rochefort and Charlton Heston playing a ruefully ruthless Richelieu. There is much in these movies that could be used in the college classroom and they are likely to hold student attention. This is probably also true of The Return of the Musketeers (released in 1989 and roughly based on the second volume of the d’Artagnan trilogy, Twenty Years Later), but that film appears to be available in the U.S. only in used VHS format.

Lester and the scriptwriter George MacDonald Fraser (author of the Flashman novels) inject dark humor both by the way the derring-do degenerates into slapstick and by their sharp contrasts between the lives of the ruling classes and those of the menu people. For example, they show the pointlessness of dueling in The Three Musketeers when d’Artagnan and Rochefort encounter each other by night on the road to Calais. The mayhem that ensues as they try to blind each other with dark lanterns and grope with their swords renders the fight an exercise in futility. As for social relations, the Musketeers, who aspire to the highest positions, steal and destroy property with joyful abandon and no thought of cost. After one particularly destructive romp through an inn, Athos pays le patron with a bag of what is supposedly coins and is actually salt. On their endless dashes though the countryside, our heroes crush crops and trample new-mown hay, to the obvious chagrin of the farmers. We do not get to hear their comments, but in the Four Musketeers we are treated to the reaction of Milady’s chaise bearers after they deliver her home. They mutter that she’s gained so much weight she should invest in a horse. All this is quite reminiscent of Robert Darnton and Natalie Davis, as are some of the sharper points made in the portrayal of the royal court. King Louis XIII acted as impatient and foolish by Jean-Pierre Cassel makes one sympathize with Richelieu’s lust for power. Geraldine Chaplin as Queen Anne is beautiful and silly. She enjoys her ride on a revolving swing so much that she demands that someone beat the servants who are not pushing her high enough. We later join them at an idyllic picnic, complete with music from a hand-pumped organ. All is delight until the camera pans the background: peasants being hanged, with Cardinal Richelieu presiding.

The gulf between Second Estate and Third is signaled visually and even through motion. The court dresses in brilliant, pristine colors—even appearing as a snowy wonderland of white for the ball at which the queen must wear her diamond studs, those glittering lynchpins of the plot. The outside world, in sharp contrast, is dull gray and tan. When the people move it is to flee their rulers or their rulers’ armies. The court processes with ponderous dignity, the slightest of motions conveying meaning, as when King Louis summons a servant with a twitch of his fingers—so he can wipe his hands on the man’s clothes! That brief incident sums up Lester and Fraser’s vision of early modern France, and it leaves the viewer wondering why it took another century to start the French Revolution.

The Musketeers’ current incarnation is the BBC series that premiered in 2014 and is about to begin a third season. The developers of the show rethought the premise, keeping the Dumas characters but seemingly laying aside the original story line to explore other topics. It’s a darker, grittier seventeenth century that seems closer to the actual past than to the novel that gave it birth. It’s not entirely realistic: there are echoes of the police procedural and the western in the plotting and costuming. The Musketeers wear leather, and the plumed chapeaux proper to the period have somehow evolved to resemble Stetsons. We witness the routine of loading, priming, ramming and cocking firearms early modern style, but there is more gunplay than seems likely in seventeenth-century Paris. To be fair, we also learn that fired guns make useful clubs in a fight. The Musketeers in this version function as a combination of Secret Service, police, and elite military unit. They interact frequently with king, queen and Cardinal, and interesting, though unhistorical, things happen: for instance, the handsome Aramis becomes the father of the future Louis XIV—a reworking of the rumors about the Sun King’s birth typical of the show’s use of history.

While The Musketeers thus affords some irritations, it also uses early modern issues and situations. The series is set before the outbreak of Louis XIII’s wars against the Huguenots, so the foreign enemy is not England, but Spain. In the second season Rochefort is presented as a Spanish agent in very deep cover, and the border tensions between France and Savoy lie at the heart of another episode. The Musketeers investigate a mystic claiming direct revelations from God, clarify the machinations of a mad astrologer, and walk the mean streets of the Paris Cour de Miracles. They break up a prostitution ring reminiscent of Hogarth’s Harlot’s Progress and are instrumental in saving a “libertine” woman accused of being a witch. They explore the religious tensions of the age: they believe they’ve uncovered a Huguenot plot against Catholics, only to encounter a Reformed divine who preaches reconciliation and helps them uncover what it is really going on—a decidedly non-religious plan to restore the fortunes of a noble family. D’Artagnan is unable to achieve a commission in the Musketeers until Milady gives him the thirty livres he needs to acquire it. In the second season, a Spanish general offers military secrets to the French because he’s being persecuted at home for his Moorish ancestry. All these could spark discussion of history but also of the differences between fiction and history.

The characters are evolving in directions that make them attractive to a contemporary audience. D’Artagnan, played by Luke Pasqualino, bursts into the Musketeer barracks in the first episode, seeking revenge for his father, who has been murdered by a renegade Musketeer masquerading as Athos. Only as the series progresses do his uncertainties and doubts emerge. He can’t persuade Constance to become his mistress. Constance, as acted by Tamla Kari, believes her husband’s threat to kill d’Artagnan. She crisply enunciates to her would-be lover the consequences for a seventeenth-century woman who leaves her husband. She prefers to wait for Bonancieux to die, which happens in the second season. She plays a full part in that season’s denouement, since d’Artagnan has taught her to shoot and use a sword.

The older Musketeers are as originally written, but each with his own twist. Tom Burke’s Athos still drinks to excess while dreaming of his lost wife. But he has to deal with her in reality, as an agent of Richelieu and Rochefort and as a member of the court, which she enters by seducing the king. Aramis, Santiago Cabera, is not an aspiring priest but a failed one due to his liking for the ladies. Now he is in love with Queen Anne and seems likely to end in very deep waters indeed. Howard Charles as Porthos offers perhaps the most interesting development of Dumas. His Porthos retains the size and strength which Dumas gave him, but in homage to the author’s Haitian ancestry, Porthos has become Afro-French. He is presented as the offspring of an unlikely marriage between a freed slave and a ruthless young noble who abandoned his African family to avoid being disinherited. Porthos grew up on the streets, joined the army and was recruited into the Musketeers by Captain Tréville, portrayed by Hugo Speers. Tréville is much more present in this version, and rather than being bewigged and blustering he is a vigorous veteran who sacrifices himself to spare his men.

Maimie McCoy’s Milady is a sharp contrast to Faye Dunaway’s version. Dunaway’s villain is as icy as the splendid snowy gowns she wears. She seems to feel nothing even when she seduces Buckingham, encounters her husband, or strangles Constance. McCoy plays Milady as an angry, angry woman. It is not until the end of the first season that we get her version of her failed marriage. While she was indeed a thief and a prostitute before meeting Athos, she was devoted to her husband. Unfortunately for both of them, Athos’ brother attempted to rape her and in resisting, she killed him.

Athos, apparently reverting to his medieval right of high justice, had her hung. But she survived the drop—not unheard of in the period—and now seeks to destroy her husband and his friends, even though it is clear the two are still intensely focused on each other. In the supporting cast Ryan Gage plays Louis XIII with a strong, if immature, personality, dependent on Richelieu and then Rochefort even while resenting the dominance of these older men. King Louis was 24 in 1625 and the series presents him so, unlike any other of the Musketeers considered here. Peter Capaldi’s Richelieu was ruthless and driven, but as ambitious for the grandeur of France as for his own. Capaldi caught something of the real Richelieu’s physical fragility and high-strung nature. It is a pity for the series that he decided to become the next Dr. Who. The comte de Rochefort, portrayed by Marc Warren, became the Musketeers’ next antagonist. Rochefort is not only a traitor; he is driven by an obsession with Queen Anne, played by Alexandra Dowling. He tries to rape the queen, which leads to the loss of his eye, since her majesty sticks a hairpin in it.

Rochefort’s revenge dominates the final shows of the second season. By its end, Dumas’ story has indeed been retold: Queen Anne has been accused of illicit passion and rescued by the Musketeers, Constance brought to (near) death for helping them, Rochefort killed by d’Artagnan, and Aramis departed for a monastery. But, always, the twists: the queen has actually had the affair and doesn’t regret it; Constance survives to spend a distinctly not chaste—but apparently blissful—wedding night with d’Artagnan; Milady redeems herself by helping to foil Rochefort and plans to start a new life in England—with Athos, although in the end he doesn’t go. Neither Porthos nor Aramis gets a girl, but the former is semi-officially adopted by Tréville through the gift of the captain’s sword. And Aramis will be pulled out of his cell to join his friends for the war with Spain that erupts as the season ends. So having left Dumas behind, the third season will explore new territory.

The Third Estate penetrates the Second to a far greater degree here than in the Lester films. The king and queen sometimes even walk through the streets and interact with their subjects, while Constance brings a sensible, if not always welcome, Third Estate presence to the court. She demonstrates her worldly savvy in saving the Dauphin from a chest infection by taking him to spend the night in a steamy commercial laundry. The court doctor, evidently a Paracelsan, had been dosing little Louis with metallic tinctures and was about to apply leaches to bring down his fever. The series’ view on early modern society is pithily summed up by King Louis’ observation that common sense is for the common people. Indeed it is. One is again left wondering what took the Revolution so long—and that is certainly a question that can be profitably explored in the classroom.

So can gender. Constance with a rapier, Queen Ann with a hairpin, Milady with an array of weapons, all call for a quick review of the presentation of women in the films.  Their portrayal parallels the perception of the role of women and the rise of women’s history. In 1921 women are nonentities. Even Milady as played by Barbara LaMarr is physically and intellectually frail–d’Artagnan takes the diamonds from her by force and easily avoids the ruse by which she tries to get them back. In the 1948 and 1973 films, wicked women are powerful: Lana Turner and Faye Dunaway are frightening each in her own way. But June Allyson as Constance has too kind a heart for her own good. Raquel Welch’s Constance is feisty, but clumsy and incompetent. She’s hilarious, but hardly a female role model. Angela Lansbury played Queen Anne in 1948. She cannot maintain her honor without the Musketeers and takes delight in tricking her husband and the Cardinal. Geraldine Chaplin’s Queen Ann is almost as despicable for her silliness as Dunaway’s Milady is for her wickedness. Only in the BBC series do women, good and bad, show agency. From Queen Anne’s determination to protect her son, to Ninon the free-thinker’s efforts to educate women, to Constance defending herself instead of allowing d’Artagnan to do it, these women control their own lives. Ladies handling swords is stretching things a little—there were such women, but they were rare. Other women show us some of the ways women could act within a male-dominated world to live lives that seemed good and right to them. Is any of this plausible? No less than Dumas’ invention.

Their portrayal parallels the perception of the role of women and the rise of women’s history. In 1921 women are nonentities. Even Milady as played by Barbara LaMarr is physically and intellectually frail–d’Artagnan takes the diamonds from her by force and easily avoids the ruse by which she tries to get them back. In the 1948 and 1973 films, wicked women are powerful: Lana Turner and Faye Dunaway are frightening each in her own way. But June Allyson as Constance has too kind a heart for her own good. Raquel Welch’s Constance is feisty, but clumsy and incompetent. She’s hilarious, but hardly a female role model. Angela Lansbury played Queen Anne in 1948. She cannot maintain her honor without the Musketeers and takes delight in tricking her husband and the Cardinal. Geraldine Chaplin’s Queen Ann is almost as despicable for her silliness as Dunaway’s Milady is for her wickedness. Only in the BBC series do women, good and bad, show agency. From Queen Anne’s determination to protect her son, to Ninon the free-thinker’s efforts to educate women, to Constance defending herself instead of allowing d’Artagnan to do it, these women control their own lives. Ladies handling swords is stretching things a little—there were such women, but they were rare. Other women show us some of the ways women could act within a male-dominated world to live lives that seemed good and right to them. Is any of this plausible? No less than Dumas’ invention.

Fred Niblo, Director, The Three Musketeers, 1921, b/w and color, 119 min, USA, Douglas Fairbanks Pictures.

George Sidney, Director, The Three Musketeers. 1948, Color, 125 min, USA, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM).

Richard Lester, Director, The Three Musketeers, 1973, Color, 106 min, Spain, USA, Panama, UK, Film Trust S.A., Este Films

Richard Lester,Director, The Four Musketeers, 1974, Color, 108 min, Spain, Panama, USA, UK, Film Trust S.A., Este Films.

Adrian Hodges, Simon Allen, Simon J. Ashford, Creators, The Musketeers, 2014–, BBC (UK), BBC America, BBC Drama Productions, BBC Worldwide

NOTES

- Roger MacDonald, “Behind the Iron Mask,” History Today 56:11 (November, 2005): 3.

- Joshua Cole, “Albert Camus’s L’hôte becomes Loin des hommes (Far From Men), Film and Fiction for French Historians: A Cultural Bulletin 6:5 (March, 2016), Accessed April 3, 2016, http://h-france.net/fffh/the-buzz/review-of-loin-des-hommes-far-from-men/

- Roxane Petit-Rasselle. “Enseignement interdisciplinaire des Trois Mousquetaires” Synergies Canada, No 1 (2009): 1.