Issue 4

Indochine & The Sea Wall

The history of France has never been just the history of France; too much of that polity and its history do not fit into the large hexagon one finds on maps of Western Europe. For hundreds of years, the notion of France included overseas territories. It still does. The French colonial empire was at its height between the First and Second World Wars, so it is fitting that various film-makers have chosen that period as a suitable moment to explore the French presence in south-east Asia. How much of the complexity of that presence can be captured by a film, especially one intended for a popular audience? Big-budget and star-led productions such as Indochine (1992) and The Sea Wall (2009) confront serious challenges when it comes to telling a colonial story. Are novels, even the semi-autobiographical ones of Marguerite Duras known as the “Indochina trilogy” on which these films (and others) are partly based, any better? How do the films and novels compare? Our expert reviewers respond by exploring the historical complexity represented – or not – in these dramatic depictions.

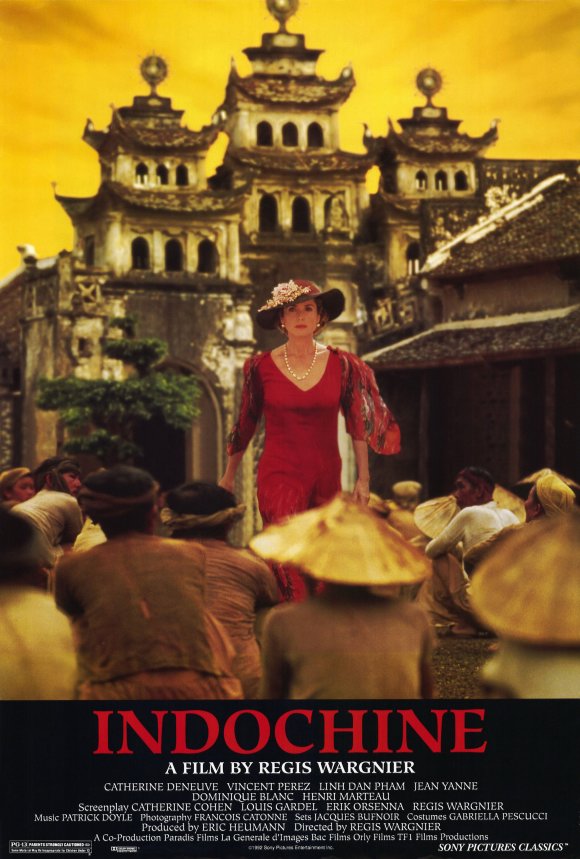

Indochine

Alison J. Murray Levine

University of Virginia

After nearly twenty years, Régis Wargnier’s Indochine (1992) still sparkles. Stylistically, it resembles Hollywood heritage films – high budget, pictorialist films that privilege visual pleasure, spectacle, and a claim to literary or historical “authenticity.” Indochine’s opulence extends to international stars (Catherine Deneuve and Vincent Perez), extensive location shooting in Vietnam and Malaysia, sweeping shots of landscapes and period sets, designer clothing by Gabriella Pescucci, and two historical consultants (Nelly Krowolski and Benjamin Stora). Well publicized and distributed, Indochine drew 3.2 million viewers in France, an Oscar win for Best Foreign Language Film, and many other awards and accolades. However, as a scholar of French cultural history and cinema, teaching in a French department, I find Indochine beautiful, irritating, and problematic. Unlike The Sea Wall, this film operates with all the subtlety and nuance of a sledgehammer. It is formulaic, melodramatic, and historically vague. And yet, I continue to assign it in courses on colonial France and film, and I believe it can also spark substantial discussion about the French empire in more general French history courses.

Indochine unfolds as an extensive flashback narrated by Eliane Devries (Deneuve), a French woman who grew up on a rubber plantation in French Indochina. Her story begins with the funeral of her best friends, Prince N’Guyen and his wife, and her subsequent adoption of their young daughter, Camille. Eliane raises Camille and remains unmarried, managing the plantation and engaging in passionate love affairs. She becomes involved with a young French naval officer, Jean-Baptiste (Perez), who also falls in love with Camille (Linh Dan Pham). As is typical in this genre, multiple love stories intertwine against a backdrop of historical conflict (in this case, the “hurricane” that ended French rule in Indochina).[1] Camille runs off to join the nationalist movement and to find Jean-Baptiste, who fathers her child. She gives birth to a son, Etienne, whom Eliane ends up raising, because Camille is imprisoned. Freed in 1936, Camille does not return to her family, preferring to continue working for independence. The film ends at the 1954 peace accords in Geneva, which Camille attends as part of the Vietnamese delegation. Eliane and Etienne are also in Geneva, as the viewer learns at the end, for Eliane to tell her story and to give Etienne the possibility of meeting his birth mother.

Indochine unfolds as an extensive flashback narrated by Eliane Devries (Deneuve), a French woman who grew up on a rubber plantation in French Indochina. Her story begins with the funeral of her best friends, Prince N’Guyen and his wife, and her subsequent adoption of their young daughter, Camille. Eliane raises Camille and remains unmarried, managing the plantation and engaging in passionate love affairs. She becomes involved with a young French naval officer, Jean-Baptiste (Perez), who also falls in love with Camille (Linh Dan Pham). As is typical in this genre, multiple love stories intertwine against a backdrop of historical conflict (in this case, the “hurricane” that ended French rule in Indochina).[1] Camille runs off to join the nationalist movement and to find Jean-Baptiste, who fathers her child. She gives birth to a son, Etienne, whom Eliane ends up raising, because Camille is imprisoned. Freed in 1936, Camille does not return to her family, preferring to continue working for independence. The film ends at the 1954 peace accords in Geneva, which Camille attends as part of the Vietnamese delegation. Eliane and Etienne are also in Geneva, as the viewer learns at the end, for Eliane to tell her story and to give Etienne the possibility of meeting his birth mother.

Panivong Norindr, Marina Heung, I, and others, have articulated many of the problems in Indochine, but it is perhaps useful to recall them briefly here.[2] Relying on individual memory as its narrative principle, the film avoids historical precision in favor of the portrayal of a French Indochina lost in the mists of time. The only date in the film appears in the last frame. Events such as the repressive treatment of nationalists, the Yen-Bay uprising, and the enslavement of peasants, while mentioned, serve merely as background material to heighten the melodrama of the protagonists’ experiences. Beautiful images seduce the viewer into complicity with Eliane’s viewpoint, serving up a foggy, mythical “Indochine” with a primordial connection to France.

Eliane experiences independence as a traumatic loss of homeland and of family. Her nostalgia permeates the entire film, and yet, because her voice is only sparsely interspersed, the viewer tends to forget that she is the narrative filter for every scene. Hers is a “domestic genealogy” of empire, in which her character and that of Camille romantically represent the familial ties between France and Indochina.[3] The colonial context is thus naturalized through the figure of the mother.[4] The representational strategies exemplify, as Marina Heung suggests, “the revisionist tactics of postcolonial representation,” perhaps even performing “the work of disavowal by gendering colonialism, by displacing its scandal onto the female.”[5]

The result is that rather than opening up a new space within which to figure colonial history, the film fixes images of the empire in memorial timelessness. Its discursive economy approaches Fredric Jameson’s definition of the nostalgia film, symptomatic of a postmodern desire for lost authenticity that evokes the past through “stylistic connotation” and memory process rather than actual historical content.[6]

Despite these problems – in part because of them – I still assign the film. To begin with, students often find it pleasurable. Its shimmering display of consumable beauty, combined with a pacing and score that soothe and fray the viewer’s emotions in familiar ways, encourages an openness to debate that I find productive. Students care about the world in the film and want to learn more. Once they begin to grapple with the problems outlined above, rich discussion about colonial France and its aftermath can follow.

Here are a few examples of paths into discussion that open from a viewing of Indochine and complementary readings. A discussion of the heritage genre, and its flowering during Mitterand’s presidency, with its concurrent wave of nostalgia for the era of the Popular Front, can help to situate the film and raise questions about its nostalgic tendencies. This can lead to the larger question of memory narratives and the legacies of colonialism in contemporary France. Addressing the students’ own visual pleasure can lead to a conversation about desire and spectator identification, and from there, to questions about how the viewer’s identification with Eliane colors the impression of historical events portrayed. I have also found Indochine useful as an introduction to scholarship on gender and the culture of colonialism. Like The Sea Wall, the film can help students to break down monolithic notions of “French colonizers” into smaller groups divided by markers such as geography, social class, profession, gender, and marital status. It pairs well with readings on European women’s experiences in the colonies and the implication of gender and power relations in discussions of nationalism, nation-building, and the imperialist project.[7] The film also invites discussion of the relationship between the French administration and educated elites in Indochina, through the characters of Tanh and his family.[8] Though artistically flawed and historically skewed, Indochine is, and will likely remain, a powerful teaching tool.

- The term “hurricane” is borrowed from Jean Noury, L’Indochine avant l’ouragan (Chartres: Imprimerie Charon, 1984).

- See, for example, Panivong Norindr, Phantasmatic Indochina: French Colonial Ideology in Architecture, Film, and Literature, (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996); Alison J. Murray, “Women, Nostalgia, Memory: Chocolat, Outremer, and Indochine,” Research in African Literatures 33:2 (2002): 235-44; Marina Heung, “The Family Romance of Orientalism: From Madame Butterfly to Indochine,” Genders 21 (1995): 222-258; Srilata Ravi, “Women, Family and Empire-building: Régis Wargnier’s Indochine,” Studies in French Cinema, 2:2 (2002): 74-82.

- The visual association between Deneuve and Marianne is unavoidable, and Eliane’s role as a colonial matriarch is also clear. Eliane mothers first Camille, then Etienne, and she also sees herself as a mother to her workers: “Tu crois qu’une mère aime battre ses enfants?” she says to one of her workers, who is being punished for desertion. He replies: “Tu es mon père et ma mère.”

- Anne McClintock, “‘No Longer in a Future Heaven’: Gender, Race, and Nationalism,” in Dangerous Liaisons: Gender, Nation, and Postcolonial Perspectives, ed. Anne McClintock, Aamir Mufti, and Ella Shohat (Minneapolis, 1997), 89-112, quote from p. 93.

- Heung, “Family Romance,” 241; Laura Kipnis, “‘The Phantom Twitches of an Amputated Limb’: Sexual Spectacle in the Post-Colonial Epic,” Wide Angle 11:4 (1989): 42-51, quote from p. 44.

- Fredric J. Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991).

- Unlike The Sea Wall, Indochine only briefly suggests the threat that white women’s presence in the colonies could pose to white male dominance, not only because of the women’s own agency but also because of their potential attraction to non-white partners. Ann Laura Stoler cites the “overwhelming uniformity with which white women were barred from early colonial enterprises” because of the threat that they posed to the boundaries of European (white male) prestige and control. “Rethinking Colonial Categories: European Communities and the Boundaries of Rule,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 31:1 (1989): 134-161, quote from p. 139. Before their love affair begins, Jean-Baptiste briefly voices this point of view by criticizing Eliane for “commanding men,” which is a man’s job.

- Additional readings can of course be tailored to the overall scope of the course. In addition to the articles specifically devoted to the film, mentioned in Note 2, I have found the following useful with Indochine: Alice L. Conklin, “Redefining Frenchness: Citizenship, Race Regeneration, and Imperial Motherhood in France and West Africa, 1914–1940,” in Domesticating the Empire: Race, Gender, and Family Life in French and Dutch Colonialism, ed. Julia Clancy-Smith and Frances Gouda (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998), 43–64; Ann Laura Stoler, “Making Empire Respectable: The Politics of Race and Sexual Morality in 20th-Century Colonial Cultures,” American Ethnologist 4:3 (1989): 634-660; Eric Jennings, “From Indochine to Indochic: The Lang Bian/Dalat palace Hotel and French Colonial Leisure, Power, and Culture,” Modern Asian Studies 37:1 (2003): 159-194; Anne McClintock, Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Context (New York: Routledge, 1995).

Régis Wargnier, Director, Indochine (1992) France/Color, Paradis Films/La Générale d’image/Bac Films/Orly Films/Ciné Cinq. Running Time (USA cut): 153 min.

The Sea Wall

Eric T. Jennings

University of Toronto

I teach an advanced undergraduate seminar on French colonial Indochina, whose subtitle runs: “histories, cultures, texts, films.” After reading a textbook, the excellent Pierre Brocheux and Daniel Hémery, Indochina: An Ambiguous Colonization, 1858-1954 (2010), students tackle a series of themes and genres which encompass prisons, métissage, urbanism and architecture, across fiction, biographies, historiography and filmic representations. I pair Panivong Norindr, Phantasmatic Indochina (1996) with several of the films he analyses so trenchantly, Indochine and The Lover. When I learned that Rithy Panh, a Cambodian director already famous for documentaries on peasants and on the Khmer Rouge,[1] was adapting Marguerite Duras’ Un barrage contre le Pacifique, a novel set in French colonial Cambodia, I leapt at what I imagined to be a useful new teaching tool.

Although Panh renders much of Duras’ text very accurately (readers of Un barrage will instantly pick up such cues as the dying horse, the automobiles, the phonographs, even the échassier au vin blanc), I was struck by some major divergences between novel and film. One has to do with the relative calm of the novel’s mercurial maternal character. The madness of the Kam household is bowdlerized through her indifference. To be sure, Panh has quite sensibly seized the anticolonial dimension of Duras’ 1950 novel, which some decried at the time as an attack on France’s empire.[2] And he has manifestly attempted to empower the peasants whom Duras treats as both timeless[3] and largely peripheral to her plot. In the novel, said peasants are visible mostly when their children perish from cholera, hunger, or malaria, or when they are enrolled to build a Sisyphean dam to keep the South China Sea out of the rice fields. In the film, conversely, they rebel, even decapitating a French official in the process.

Although Panh renders much of Duras’ text very accurately (readers of Un barrage will instantly pick up such cues as the dying horse, the automobiles, the phonographs, even the échassier au vin blanc), I was struck by some major divergences between novel and film. One has to do with the relative calm of the novel’s mercurial maternal character. The madness of the Kam household is bowdlerized through her indifference. To be sure, Panh has quite sensibly seized the anticolonial dimension of Duras’ 1950 novel, which some decried at the time as an attack on France’s empire.[2] And he has manifestly attempted to empower the peasants whom Duras treats as both timeless[3] and largely peripheral to her plot. In the novel, said peasants are visible mostly when their children perish from cholera, hunger, or malaria, or when they are enrolled to build a Sisyphean dam to keep the South China Sea out of the rice fields. In the film, conversely, they rebel, even decapitating a French official in the process.

One wonders whether a juste milieu might have been achieved. In the film, Duras’ peasant victims have not really been endowed with agency (we still don’t know any names, and to an average North American student, their language could be Khmer just as easily as it could be Vietnamese), but they deploy a form of violence, which, to some of my students at least, seemed to surpass even that of the colonizers in this rendition.[4] Panh attributes this particular departure from the novel to the fact that he is Cambodian. He adds that this enabled him to stress the political dimension of Duras’ novel, rather than what he calls her “schmaltzy side.”[5]

The problem is that the novel’s most potent political statement, revolving around colonial extraction, and centering on Saigon’s white quarter, is curiously cut from the film. Gone is Duras’ unforgettable depiction of colonial vampirism and extraction, where blood and latex intermingle. Gone is the lengthy discussion of colonial segregation, a segregation inscribed into Saigon’s very fabric in Duras’ novel. Gone is her brilliant analysis of white and whiteness.[6] Does Panh’s politicization of Duras’ peasants ultimately work? Several students told me that they found Panh’s film to be, overall, oddly more suffused with colonial nostalgia than Régis Wargnier’s Indochine. Perhaps the final scene contributed to this impression. We will come to that soon.

In what is less of a rupture than an interpretation, Panh depicts the wealthy Monsieur Jo, the “Northern planter” enamored with the teenage Suzanne, as Asian. In this respect, Panh has seized upon the ambiguity of The Sea Wall, where Monsieur Jo’s race is never made explicit (Suzanne’s vulgar, boorish, and racist brother does call him a “monkey,” but that hardly offers a definitive clue).[7] Yet, in some ways, Panh has also vaulted forward one novel, to Suzanne’s Asian lover in L’Amant. The problem is that the lover’s ethnic identity – first ambiguous in Un barrage (1950), then Chinese in L’Amant (1984), and finally Manchurian in L’Amant de la Chine du Nord (1991), is anything but trivial. For one thing, the male lover is eroticized in the second and third installments of Duras’ Indochina trilogy, but not in the first. Mostly, the original Durassian shift has to do with the author’s own life story; indeed, the Indochina trilogy is more than loosely autobiographical. In a hypothesis based on Duras’ own notes, Jean Vallier has suggested that the actual Marguerite Donnadieu’s lover, Léo, was in fact Vietnamese. If such were the case, Duras’ reckoning with this colonial transgression took place over the forty-one years that it took to compose the Indochina trilogy, with Duras recasting him first as a hazy “Northern planter” – at a time when she dared not reveal to her mother that he was Asian – then as a wealthy Cholon Chinese, and finally as Manchurian.[8] In other words, injecting the explicitly racialized relations of L’Amant into the earlier Barrage jumbles the cards. The result is that when contrasting Panh’s film to Duras’ trilogy, gender and power relations do not keep pace with racial ones.

Finally, this reviewer and his students were left wondering about the film’s final scene, showing a present-day fertile plot purportedly still known as the “white woman’s.” In a classic bookending, the field has gone from desolation in the movie’s opening scene, to lushness in its closing one. Furthermore, Joseph is seen handing over stewardship of the land, and the gun that protects it. Is one to deduce that the family has been ascribed a Cambodian indigenousness? Or that the mother’s determination, verging on madness, was ultimately rewarded? Or are Cambodians supposed to actually miss her? Of course, this dash to the present also leapfrogs over Cambodia’s greatest tragedy, its genocide.

All of this said, the film certainly struck my class as well suited to a seminar on French Indochina. And it clearly stimulated debate. The discussion that followed the screening was lively, and touched upon several of the points evoked above, and many more. In the film review I had students write, one even analyzed the musical score, puzzling over the fact that no Cambodian music was chosen.[9] Indeed, is there anything specifically Cambodian about this story with which to debunk the common perception that the Duras trilogy are “Vietnam novels”? The problem is that in order fully to undertake such a class discussion, students would ideally have read all three of Duras’ Indochina novels, and perhaps one of her biographies. Still, viewing Panh’s film against the grain of Norindr’s argument about “Indochic” (and hence Norindr’s analysis of three other films, all French, and all released in 1992) seemed a useful assignment. If my class was any indication, most found that the film fell headlong into the “Indochic” tropes and traps that Norindr decries.[10]

- Rithy Panh, Rice People (1994) and S21 (2003).

- Interview with Rithy Panh at http://twitchfilm.com/interviews/2008/09/tiff08-un-barrage-contre-le-pacifique-the-sea-wallinterview-with-rithy-panh.php.

- Duras evokes “une torpeur millénaire.” Duras, Un barrage contre le Pacifique, (Paris: Gallimard, 1950), 30. On p. 117, she notes “Il y avait mille ans que c’était comme ça.”

- To be fair, Panh does depict everyday colonial violence, in the form of chain gangs and forced labor, for instance.

- Interview with Rithy Panh (see note 2).

- Duras, Un barrage, 167-170.

- Duras, Un barrage, 42.

- Jean Vallier, C’était Marguerite Duras (Paris: Fayard, 2006), 379-385. According to Vallier (p. 385) Marguerite Donnadieu/Duras apparently refused to write of the lover’s Asianness so long as her mother was still alive.

- John Cowling, film review for HIS 467H, University of Toronto, Fall 2010.

- Panivong Norindr, Phantasmatic Indochina (Raleigh: Duke University Press, 1996).

Rithy Panh, Director, Un barrage contre la pacifique [Sea Wall] (2009), France, Cambodia, Belgium/Color, Catherine Dussart Productions (CDP)/Studio 37/France 2 Cinéma, Running Time: 115 min.