Alyssa Goldstein Sepinwall

California State University, San Marcos

One of the greatest literary classics of the twentieth century was Primo Levi’s Survival in Auschwitz (first published in English in 1958). In this powerful memoir, Levi recounted the horrors of everyday life for Jews in Nazi death camps. Beyond offering detailed testimony, Levi used his experience to ask profound questions about what it means to be human. Indeed, the original title of his book was If This is a Man (Se questo è un uomo). Through Levi’s text and other memoirs, readers could move from an abstract idea of the Shoah (with millions of faceless victims) to a more concrete understanding of the humanity and suffering of individuals. As the corpus of Holocaust memoirs has grown, it has become possible to identify horrific commonalities as well as no-less-gruesome differences between individual fates. With texts by female survivors added to better-known ones by Elie Wiesel and others, scholars have been able to move beyond generalizing from men’s experiences to analyzing how gender mattered in the camps.[1]

Unfortunately, scholars have no If This Is a Man from a survivor of New-World slavery. They have a handful of exceptional slave narratives such as those written by Olaudah Equiano and Solomon Northrup. However, in general, African slaves were forbidden to read or write, in contrast to the victims of the Holocaust who had lived in freedom and been educated before their deportation to the camps. Unlike Anglo-American scholars, students of the French Caribbean have no narrative akin to Equiano’s or Northrup’s, let alone a large corpus of memoirs that would help us understand slaves as individuals and identify variations in their experiences.[2]

How then can scholars learn about slaves’ everyday life in the French colonies? Historians have long relied on sources such as plantation records, which tally numbers of slaves, noting their birth and death rates and the names they were assigned. They can also turn to treatises such as Moreau de Saint-Mery’s 1797 depiction of colonial society in Saint-Domingue.[3] Of course, these sources describe slavery from colonists’ perspectives rather than that of slaves. Slavery offers an extreme example of what Michel-Rolph Trouillot has observed about archives in general, that they are filled with silences and imbalances because it is the victors who leave records.[4] Court transcripts provide one potential site where we can hear enslaved voices. Yet these are not unmediated, as historians have also noted in regard to peasant and subaltern testimonies. Slaves were compelled to testify in particular cases, their words transcribed by others, and they were at risk if they related inappropriate behavior by their owners. Historians are thus greatly constrained when trying to understand slaves’ interior lives.

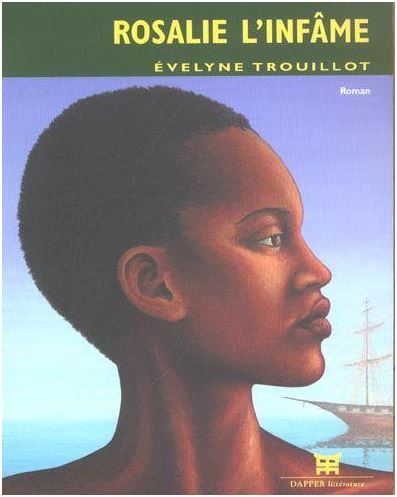

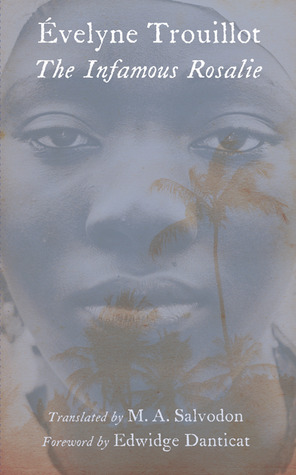

Évelyne Trouillot’s brilliant novel The Infamous Rosalie (originally published 2003 in Paris as Rosalie l’Infâme and translated into English in 2013) seeks to fill this void. Trouillot has produced a fictional analog to Survival in Auschwitz since none exists in the archives – from a female slave’s perspective. Relying on existing scholarship as faithfully as she can, Trouillot imagines a slave’s existence. What did slaves see and what did they think? How did their experiences vary? Her book also offers a more compelling account of the background to the Haitian Revolution than many existing histories. Finally, she uses slavery to raise big questions about the purpose of life and whether life as a slave was worth living. A beautifully written short novel with an excellent translation by M.A. Salvodon, The Infamous Rosalie deserves to be far better known in the U.S. It is eminently worthy of becoming a new “classroom classic.”

Évelyne Trouillot’s brilliant novel The Infamous Rosalie (originally published 2003 in Paris as Rosalie l’Infâme and translated into English in 2013) seeks to fill this void. Trouillot has produced a fictional analog to Survival in Auschwitz since none exists in the archives – from a female slave’s perspective. Relying on existing scholarship as faithfully as she can, Trouillot imagines a slave’s existence. What did slaves see and what did they think? How did their experiences vary? Her book also offers a more compelling account of the background to the Haitian Revolution than many existing histories. Finally, she uses slavery to raise big questions about the purpose of life and whether life as a slave was worth living. A beautifully written short novel with an excellent translation by M.A. Salvodon, The Infamous Rosalie deserves to be far better known in the U.S. It is eminently worthy of becoming a new “classroom classic.”

Alhough the English translation of Trouillot’s book has received few reviews,[5] the French version is better known, and a growing body of literary criticism has approached Rosalie from different angles. Scholars have looked at the novel, for example, as a story of gender-based resistance to slavery or as a Caribbean detective story.[6] In my view, the importance of the novel – and its usefulness for historians in the classroom – exceeds these particular genres. One of The Infamous Rosalie’s main accomplishments is its ability to recapture the past. In many ways, Trouillot is the ideal person to write what Danielle Legros Georges has termed a “neoslave narrative.”[7] She is one of Haiti’s leading novelists, as well as a professor of French literature at the Université d’État d’Haïti. She also comes from a family of important Haitian historians. Besides her brother Michel-Rolph (a major figure in recent Anglophone historical theory),[8] Évelyne is the niece and daughter, respectively, of two of Haiti’s leading historians of the 1950s-1960s, Hénock and Ernst Trouillot. The Trouillot brothers wrote groundbreaking work on the history of Haiti, much of which has been overlooked or forgotten by Anglophone historians.[9]

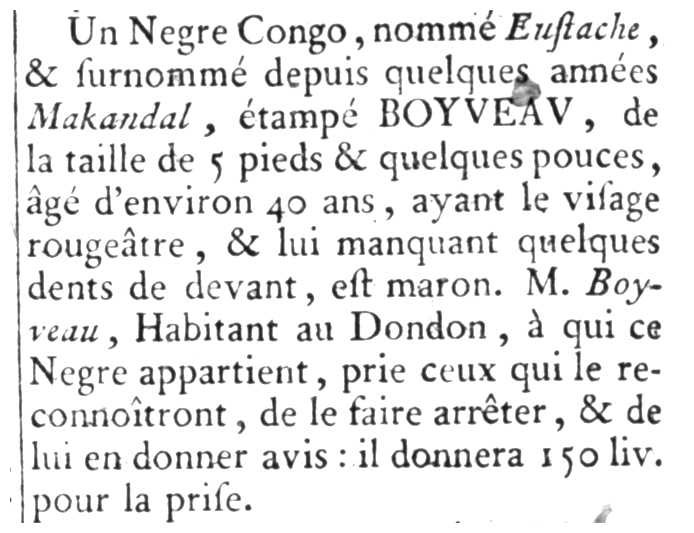

In many ways, The Infamous Rosalie builds on work by the Trouillots. In order to reverse the archival silences that Michel-Rolph identified in Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (1995), Evelyne Trouillot drew on work by her uncle and other historians, such as Hénock’s articles in the Revue de la société haïtienne d’histoire et de géographie.[10] She also read a great many primary sources. For example, her characters refer to runaway slave advertisements in real periodicals such as the Affiches américaines. Trouillot notes her “Afterword” that she did not set out to write a historical novel. However, she was haunted by a story she had read (in Lucien Abénon, Jacques de Cauna, et al., La Révolution aux Caraïbes [1989]) about an Arada midwife and her efforts to resist the slave system. While historians are limited to writing about what they find in archives, Trouillot felt that, as a novelist, she would have the freedom to “imagine and create men, women, and children living through this infamy filled with complex passions and emotions” (pp. 131-2). Indeed, as the Haitian-American writer Edwidge Danticat writes in her Foreword to Rosalie, “The Code noir, the brutal decree passed in 1685 …, gives us some idea what life was like for a slave…. Yet we rarely hear – even in fiction – from ordinary people, such as Lisette, the narrator of the book, about their daily activities, their few joys, and their constant agonies and pain” (p. vii). As Danticat’s comment indicates, even if The Infamous Rosalie is hardly an authentic primary source like the Code noir, it has the potential to fill some of those archival “silences.”

Lisette, the protagonist, is a Creole (New World-born) slave. She is atypical in many ways, with a relatively elite position in the plantation’s “big house.” Notwithstanding savage beatings which all slaves endured, she still has all her limbs and her beauty. Moreover, despite molestation by the master’s son, she has faced less sexual abuse than many other slaves. Because she was born into slavery, her condition is less shocking to her than to her African-born kin. “As a Creole,” she observes, “I can barely imagine a plantation without whites, without a master and a mistress” (p. 51). As a child, Lisette served as the best friend (but also occasional whipping girl) of the master’s daughter Sarah; as an adult, she is viewed as a beautiful object. When her mistress goes into town, she brings along Lisette and other attractive house slaves and allows them to dress up (“The mistress likes to surround herself with beautiful people” [p. 34]).

Lisette, the protagonist, is a Creole (New World-born) slave. She is atypical in many ways, with a relatively elite position in the plantation’s “big house.” Notwithstanding savage beatings which all slaves endured, she still has all her limbs and her beauty. Moreover, despite molestation by the master’s son, she has faced less sexual abuse than many other slaves. Because she was born into slavery, her condition is less shocking to her than to her African-born kin. “As a Creole,” she observes, “I can barely imagine a plantation without whites, without a master and a mistress” (p. 51). As a child, Lisette served as the best friend (but also occasional whipping girl) of the master’s daughter Sarah; as an adult, she is viewed as a beautiful object. When her mistress goes into town, she brings along Lisette and other attractive house slaves and allows them to dress up (“The mistress likes to surround herself with beautiful people” [p. 34]).

Despite Lisette’s advantages, she lives in the constant shadow of violence, as does every slave; on any given day, she or a friend could be arbitrarily whipped or killed. The novel begins with Lisette walking past the site where, the previous night, a slave named Paladin was burnt to death, while his children and others were forced to watch. Over the course of the novel, Trouillot has Lisette become increasingly aware of the utter inhumanity of the slave system. She surrounds Lisette with a collection of matriarchs, such as her Grandmother Charlotte, who tell her about their experience of capture:

Despite Lisette’s advantages, she lives in the constant shadow of violence, as does every slave; on any given day, she or a friend could be arbitrarily whipped or killed. The novel begins with Lisette walking past the site where, the previous night, a slave named Paladin was burnt to death, while his children and others were forced to watch. Over the course of the novel, Trouillot has Lisette become increasingly aware of the utter inhumanity of the slave system. She surrounds Lisette with a collection of matriarchs, such as her Grandmother Charlotte, who tell her about their experience of capture:

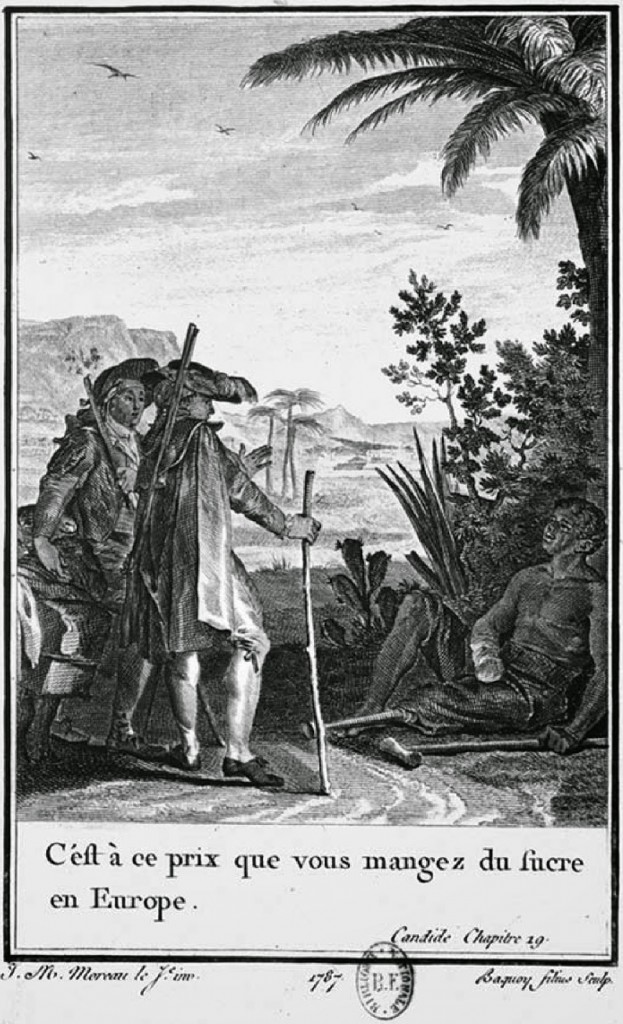

Alas, you’ve witnessed the buying and selling of human beings since the day you were born. It’s true you didn’t feel those hands on your skin, rubbing it sometimes to see if it was really shiny or the product of lemon juice and gunpowder. No one forced open your lips to examine your teeth. No buyer ever spit in your face to make you understand that while there may have been physical closeness between you and him, there was no intimacy. But Lisette, you know how this can tear up the insides of a human being (p. 80).

Charlotte also explains to Lisette why literacy itself is a horror to many African-born slaves: “Shortly after being inspected and purchased, we were branded. The surgeon… used red-hot branding irons made of silver…. TR, the initials of the slave ship, the only letters I ever learned, were from the ship that brought me here. The Rosalie. Your eyes tell me that you would have wanted me to learn other letters…. For me it’s too late: the alphabet will always embody the character of hell” (p. 80).

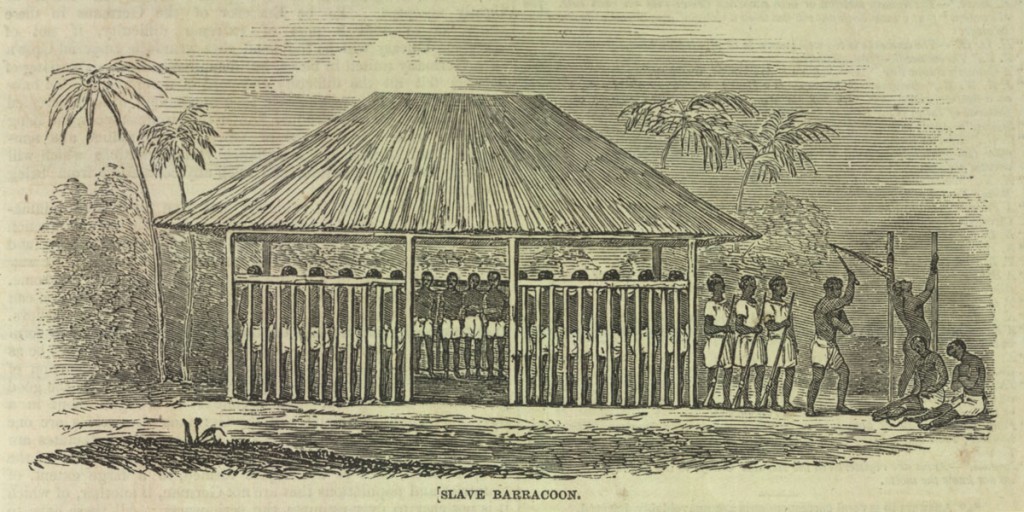

Through Grandma Charlotte and other characters, Trouillot exposes readers to slave perspectives other than Lisette’s; they provide a more thorough understanding of the diverse experiences of enslaved persons. Charlotte teaches Lisette (and the reader) about the barracoons, the holding camps in Africa where slaves were kept before the Middle Passage. Charlotte explains that, “for me, the barracoons are the wound that will always bleed deep inside me. That was when I knew for sure that a large part of me had been buried…. I was no longer an Arada woman who loved the sun and the sea. To me the barracoons represented the beginning of night, the end of liberty… (pp. 78 – 79).” As Marie Frémin has observed, the word barracon has disappeared from French dictionaries; one of Trouillot’s achievements is thus restoring this side of the slave experience to our consciousness.[11]

Rather than focusing only on the anguish of being a slave, Trouillot seeks to recreate the many emotions slaves likely felt in the course of their daily lives. Amidst near-constant sadness, Lisette finds intermittent pleasures: the shade of a poison-wood tree, the release of dancing with a childhood friend, the comfort of sleeping in the arms of her lover Vincent, the sweetness of a banana. Lisette also gains strength from her maternal elders’ stories about Arada culture and their life before slavery. Trouillot’s characters console themselves with small acts of resistance, like meeting an old Jesuit priest who treats them with respect; or Lisette’s wearing gold earrings that Sarah gave her, even though they are forbidden to a slave.

Rather than focusing only on the anguish of being a slave, Trouillot seeks to recreate the many emotions slaves likely felt in the course of their daily lives. Amidst near-constant sadness, Lisette finds intermittent pleasures: the shade of a poison-wood tree, the release of dancing with a childhood friend, the comfort of sleeping in the arms of her lover Vincent, the sweetness of a banana. Lisette also gains strength from her maternal elders’ stories about Arada culture and their life before slavery. Trouillot’s characters console themselves with small acts of resistance, like meeting an old Jesuit priest who treats them with respect; or Lisette’s wearing gold earrings that Sarah gave her, even though they are forbidden to a slave.

Still, as the novel unfolds, Lisette sees slave life as increasingly unbearable. She gradually realizes the anguish and excruciating choices faced by other house slaves. As planters’ fears of being poisoned increase, the small things that have made life tolerable for her (like dances) are banned. Meanwhile, she overhears alarming statements from planters while serving dinner; colonists outdo each other in describing the torture they will inflict to stop the poisonings. Lisette becomes “seized by the crushing truth that I am nothing but an object at the mercy of whites…. They can burn us slowly, blaze us like a torch, and make us shake like a kettle…. We’re at their mercy, and nothing will change unless we do something” (pp. 110, 112-3).

Ultimately, Lisette and the novel’s other slaves have to decide whether life is worth living in this form: is a slave better off dead? The novel’s characters make a variety of choices, some of which simply involve “choosing one’s own hell.” And yet, Trouillot also emphasizes that the will to live was indomitable, as slaves fought to protect themselves from torture or simply to see the sun rise the next day.

To a much greater extent than most historical fiction, the book’s historical perspective places it squarely in line with recent historiography on the Haitian Revolution. Trouillot very deliberately aimed to shift attention away from the great leaders on whom Haitian historiography has traditionally focused to the experiences of the common slave. In a 2005 interview excerpted in the book’s Foreword, she explained: “The emphasis was always put on the great figures, the heroes, and not on the mass of enslaved and of newly freed slaves. While writing Rosalie l’Infâme, I learned about the struggles of the enslaved women, men and children … to maintain their dignity” (p. viii). Trouillot later wrote: “it is the unspoken aspects of history that interest me: what has not been said, what is not taught at school.”[12] In this regard, Rosalie fits well with the writings of historians such as Carolyn Fick, who has sought to recover the history of Saint-Domingue slavery from below; John Thornton, who has emphasized the African cultural roots of Saint-Domingue’s slaves; and of course Michel-Rolph, who has striven to express the unrecorded stories that “no history book can tell.”[13]

To a much greater extent than most historical fiction, the book’s historical perspective places it squarely in line with recent historiography on the Haitian Revolution. Trouillot very deliberately aimed to shift attention away from the great leaders on whom Haitian historiography has traditionally focused to the experiences of the common slave. In a 2005 interview excerpted in the book’s Foreword, she explained: “The emphasis was always put on the great figures, the heroes, and not on the mass of enslaved and of newly freed slaves. While writing Rosalie l’Infâme, I learned about the struggles of the enslaved women, men and children … to maintain their dignity” (p. viii). Trouillot later wrote: “it is the unspoken aspects of history that interest me: what has not been said, what is not taught at school.”[12] In this regard, Rosalie fits well with the writings of historians such as Carolyn Fick, who has sought to recover the history of Saint-Domingue slavery from below; John Thornton, who has emphasized the African cultural roots of Saint-Domingue’s slaves; and of course Michel-Rolph, who has striven to express the unrecorded stories that “no history book can tell.”[13]

In the classroom, Fick’s Making of Haiti and Trouillot’s Infamous Rosalie would be a perfect pairing. Both deemphasize the French Revolution as the cause of the revolution in Saint-Domingue and highlight the resistance by slaves (whether brazen acts like revolt or less visible ones like infanticide) that existed since their capture in Africa. Trouillot’s story is set on a plantation in the 1750s, in the midst of the rebel slave Makandal’s poisoning scare, an episode examined by Fick. Like Fick for the period 1750 – 1789, Trouillot highlights subtle kinds of resistance. One of the major historiographical debates about the Haitian Revolution has revolved around whether it was the result of long-standing internal forces or of the events of 1789, and the novel helps bring such issues to life.[14] The novel’s questioning of what makes human life meaningful can also stimulate lively debate. Even though Rosalie is a fictional memoir and Survival in Auschwitz a real one, juxtaposing the two could spark profound discussions. Students well-versed in modern literature might also consider how a real narrative from that time (if only one existed) might have differed from this reimagined one.[15] Finally, the book would pair well in historical theory classes with Silencing the Past. Reading Évelyne’s work against her brother’s would generate discussions about history versus fiction, and whether a novel like hers might be truer to the past than textbooks filled with the kinds of silences that her brother exposed.

While such discussions would leave room for a variety of perspectives, it is undeniable that The Infamous Rosalie offers deeply grounded, highly plausible speculations about the daily lives – and inner worlds – of slaves. Trouillot highlights how women’s experiences under slavery varied from men’s; she also brings to life current historiographical debates. Poetically written and intensely readable, The Infamous Rosalie is a model historical novel; it fills gaps in the archives by layering creative speculations onto historical data. And Lisette herself is an ideal companion through the plantation, so fully fleshed out that it is easy to imagine her as real.

While such discussions would leave room for a variety of perspectives, it is undeniable that The Infamous Rosalie offers deeply grounded, highly plausible speculations about the daily lives – and inner worlds – of slaves. Trouillot highlights how women’s experiences under slavery varied from men’s; she also brings to life current historiographical debates. Poetically written and intensely readable, The Infamous Rosalie is a model historical novel; it fills gaps in the archives by layering creative speculations onto historical data. And Lisette herself is an ideal companion through the plantation, so fully fleshed out that it is easy to imagine her as real.

Against all odds, an enterprising historian may someday find a manuscript written by a female house slave in Saint-Domingue – or, even more amazingly, a cache of manuscripts by different slaves. In their absence, The Infamous Rosalie does a great service in helping us imagine what such texts might have looked like, and in humanizing the slaves of Saint-Domingue.

Évelyne Trouillot, The Infamous Rosalie, trans. by M.A. Salvodon, foreword by Edwidge Danticat. Lincoln: The University of Nebraska Press, 2013. 132 pp. [French editions available as Rosalie l’Infâme. Paris: Dapper, 2003, and Port-au-Prince: Éditions Presses Nationales d’Haïti, 2007].

- On this point, see Dalia Ofer and Lenore J. Weitzman, eds., Women in the Holocaust (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998); and Sonja M. Hedgepeth and Rochelle G. Saidel, eds., Sexual Violence Against Jewish Women during the Holocaust (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2010).

- Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the life of Olaudah Equiano… (London, 1789; available in multiple reprint editions); Solomon Northup, Twelve Years a Slave (Auburn, NY: Derby and Miller, 1853).

- M. L. E. Moreau de Saint-Méry, Description topographique, physique, civile, politique et historique de la partie française de l’isle Saint-Domingue… (Philadelphia/Paris, 1797), excerpted and translated into English as A Civilization That Perished: The Last Years of White Colonial Rule in Haiti, trans. Ivor D. Spencer (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1985).

- See Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press, 1995).

- The only formal reviews the book has received thus far are from those of Barbara Hoffert, review in Library Journal 138, no. 15 [Sept. 15, 2013], 66 (which called it a “remarkable little book]) and Danielle Legros Georges, review in Women’s Review of Books 31, no. 4 (Jul/Aug 2014): 26-7.

- See for instance Antoinette Sol, “Histoire(s) et traumatisme(s): l’infanticide dans le roman féminin antillais,” The French Review 81, no. 5 (2008), 967- 984; Brinda Mehta, “Diasporic Fractures in Colonial Saint-Domingue: From Enslavement to Resistance in Évelyne Trouillot’s Rosalie l’Infâme,” in Mehta, Notions of Identity, Diaspora, and Gender in Caribbean Women’s Writing (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 29 – 61; Renée Larrier, “Legacies and Lifelines in Evelyne Trouillot’s Rosalie L’Infâme,” Dalhousie French Studies 88 (Fall 2009), 135 -145; Marie Frémin, “Écrire la mémoire de l’esclavage en Haïti: Pour une réappropriation de l’Histoire par le peuple: Évelyne Trouillot et Rosalie l’Infâme,” and Jason Herbeck, “Le Polar aux Antilles et le cas de Rosalie l’Infâme d’Évelyne Trouillot,” both in Nadève Ménard, ed., Ecrits d’Haïti: perspectives sur la littérature haïtienne contemporaine (1986-2006) (Paris: Karthala, 2011), 21 – 37, 279 – 290; Laurence Clerfeuille, “Marronage au féminin dans Rosâlie l’Infame d’Évelyne Trouillot,” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 16, no. 1 (2012): 33 – 44. See also Laurent Dubois’s favorable comparison of Rosalie l’Infâme to other novels on the Haitian Revolution, such as Isabel Allende’s Island Beneath the Sea (“The Buzz: Unwritten Stories,” FFFH 1, no. 3, para. 5). Rosalie had a wider reception among the French reading public; it was reviewed in L’Humanité, and won the Prix Soroptimist de la romancière francophone.

- See Legros Georges, 26.

- On the arguments and impact of Silencing the Past, see Sepinwall, “Still Unthinkable? The Haitian Revolution and the Reception of Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s Silencing the Past,” Journal of Haitian Studies 19, no. 2 (Fall 2013): 75 – 103.

- See for instance Catts Pressoir, Ernst Trouillot, and Hénock Trouillot, Historiographie d’Haïti (Mexico: Instituto Panamericano de Geografía e Historia, 1953); and Hénock Trouillot, La condition des travailleurs à Saint-Dominque (Port-au-Prince: Impr. des Antilles, 1969).

- Interview with E. Trouillot via email, April 2, 2014.

- Frémin, 26.

- Comments by E. Trouillot in J. Michael Dash, ed., “Roundtable: Writing, History, and Revolution,” Small Axe 9, no. 2 (2005): 189 – 199.

- Fick, Making of Haiti: The Saint-Domingue Revolution from Below (Knoxville: Univ. of Tennessee Press, 1990); John K. Thornton, “‘I am the Subject of the King of Congo’: African Political Ideology and the Haitian Revolution,” Journal of World History 4, no. 2 (Fall 1993): 181 – 214; and M.-R. Trouillot, Silencing the Past, 71. See also Deborah Jenson, Beyond the Slave Narrative: Politics, Sex, and Manuscripts in the Haitian Revolution (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2011).

- For more on Makandal, see Fick, Making of Haiti, ch. 2; on historiographical debates about the Haitian Revolution, see Sepinwall, Haitian History: New Perspectives (New York: Routledge, 2012), section I.

- On the modernity of the narrative, see Legros Georges, 26-7.