Colin Jones

Queen Mary, University of London

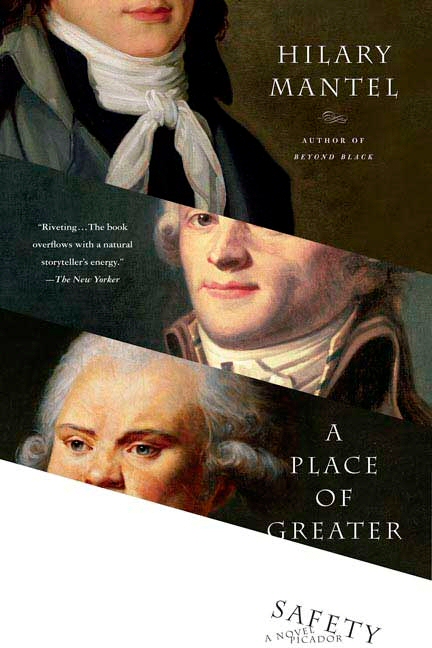

The plaudits for Hilary Mantel are already starting to appear, as the second volume of her trilogy based on the life of Henry VIII’s minister, Thomas Cromwell, is launched this month in England.The first, Wolf Hall, enjoyed huge success, winning in 2009 Britain’s most prestigious literary prize, the Man Booker. Mantel enthusiasts should try her back catalogue. Her A Place of Greater Safety (1992) is the most compelling historical novel devoted to the French Revolution that I have been fortunate enough to encounter. Wolf Hall ends with “the sickening sound of the axe on flesh,” as Sir Thomas More encounters the block, and this eerily echoes the bravura description of the guillotining of Danton at the end of A Place of Greater Safety. The latter novel is structured around the interlocking lives of Danton, Robespierre, and Camille Desmoulins. Mantel follows them from their childhood, fast-forwarding through their adolescence, to the experience of Revolution of 1789 and the climacteric spring of 1794.

When I first read this huge novel,[1] I was stunned and agog: stunned at the novelistic power of the narrative, the deftness of its emplotment and the sharpness of the writing; and agog (in that snooty way we historians can affect) at the thoroughness of its historical grounding. Mantel is a novelist who sometimes writes on historical subjects – she has authored twice as many contemporary novels (eight) as historical ones. But she clearly revels in historical research, luxuriates in historical detail and thrills to the cocktail of power and violence that accompany revolutions.[2] Her A Place of Greater Safety obliges us to question some of the fundamental ways that we have approached the Revolution, and in particular the Terror, and manages to do this in imaginative ways not available to historians (and all the more inspiring for that).

When I first read this huge novel,[1] I was stunned and agog: stunned at the novelistic power of the narrative, the deftness of its emplotment and the sharpness of the writing; and agog (in that snooty way we historians can affect) at the thoroughness of its historical grounding. Mantel is a novelist who sometimes writes on historical subjects – she has authored twice as many contemporary novels (eight) as historical ones. But she clearly revels in historical research, luxuriates in historical detail and thrills to the cocktail of power and violence that accompany revolutions.[2] Her A Place of Greater Safety obliges us to question some of the fundamental ways that we have approached the Revolution, and in particular the Terror, and manages to do this in imaginative ways not available to historians (and all the more inspiring for that).

A Place of Greater Safety eschews panoramic description, ex cathedra historical judgements, and the wide-angle lens on revolutionary process. This is unsurprising in a way: unless one happens to be Leon Tolstoy, the novel form lends itself poorly to big picture description and analysis. Apart from a few mob-like instantiations, the Parisian masses have no place in A Place of Greater Safety.[3] The provinces too are largely absent, featuring essentially as places where the characters grow up, where they are damaged in some way and where (with the exception of Danton, whose hankering for a return to Arcis-sur-Aube is a foolish chimera) they wish never to return. Mantel evokes the broader political context essentially through clipped authorial asides and through the conversations of her subjects. This makes for one of the novel’s most striking features. For Mantel must be one of the wittiest and most amusing writers of imagined conversation writing in English today. What we lose on the swings of verisimilitude we gain on the roundabout of sheer delight.

One of the great topoi of the historiography of the Terror has always been the notion of the Revolutionary juggernaut crushing private individuals in its path. Mantel contributes to this tradition, but complicates and enriches it in very striking ways. She demonstrates with graphic detail and insight the extent to which the sense of fear, anxiety, and victimhood caused by the Terror was shared by the great revolutionary protagonists. This is more than a case of Saturn devouring his children.[4] It is really Saturn devouring himself, that is to say, revolutionaries constructing the Terror at the same time that they fell victim to the machine that they were fabricating. Danton, Desmoulins and Robespierre exhibit as many of the symptoms of anxiety, fear of betrayal, and doomed fatalism as any captured emigré marquis, hapless Farmer General or non-juring priest, sweating it out at the Conciergerie prison. In the Terror, no “place” is “safe,” least of all the Committee of Public Safety. The characters proceed ineluctably towards their doom strapped to a mast of their own creation.

Focussing on the psychology and motivations of leading individuals is not a novelistic monopoly. In fact, the historiography of the French Revolution is absolutely saturated with obsessions about such figures. The thunderous disagreements at the start of the twentieth century between Aulard and Mathiez on the respective merits of Danton and Robespierre set the tone. The Jacobino-Marxist tradition of Revolutionary historiography taken forward from Mathiez by Georges Lefebvre, Albert Soboul and Michel Vovelle was almost wholly pro-Robespierre (and consequently anti-Danton) in its sympathies. The historians most opposed to this tradition have, in contrast, tended to smile indulgently on Danton.[5]

The way in which Mantel interweaves the politics of government and terror with gender politics is one of the most striking aspects of the novel. It is not just that no place is safe, no private life immune from the reach of Terror. In addition, Mantel places Danton, Robespierre and Desmoulins in an imagined but believable marital and sexual ecology. After all, it is not far-fetched to think that the politicians of the Terror went home at night and tried to live normal lives. Mantel’s perspective brings to the front of the stage the female figures conventionally lost from view. In particular, she conjures up from the shadows a whole dramatis personae of women whose existence framed the lives of the three male protagonists. It must be said that just about all of them are portrayed unflatteringly. Mantel started writing A Place of Greater Safety in the 1970s, coming back to finish it off in 1991.[6] The work thus shows few traces of the ‘gender turn’ within French Revolutionary historiography that really started in earnest at the time of the bicentenary. Camille Desmoulins’s wife Lucile is memorably ghastly, the priggish and self-obsessed Manon Roland scarcely less so. The Duplay sisters include a drably scheming Eléonore and a sex-obsessed Elisabeth. Danton’s young second wife is a dim-witted, if sweet, dolt. Théroigne de Méricourt is here, but only in a bloodcurdlingly psychopathic incarnation. The wince-making portrayals highlight the extent to which the women who lived in the ambit of Revolutionary leaders were as much subject to the influences of Terror as the men around whom they revolved, fluttered and schemed.

For me, the most brilliant characterisation in the novel is that of Camille Desmoulins. He and his wife Lucile are presented as a kind of couple maudit, damned souls and capricious free spirits addicted to self-gratifying pleasure in all the forms that life and revolutionary politics have on offer (principally, sex and power). Though Lucile fights off the attentions of a string of suitors (including Danton), Camille is a bed-hopping bi-sexual enfant perdu, pausing in his wild and hectic course only to inspire Parisians to attack the Bastille, to endorse political lynching, to launch polemical assaults on former friends (e.g. Brissot) and, finally, to urge retreat from Terror. It would be easy thoroughly to deplore Camille had not Mantel equipped him with a charm, a riotous sense of fun and a wicked wit that force his contemporaries (as they force us) to suspend our moral qualms. This allows us even to feel a measure of sympathy for him as he adopts the Dantonist road towards indulgence, aware that, in the context of the Great Terror, this could only lead to the grave, that ultimate “place of greater safety,” whose spectre hangs sombrely over the final sections of the novel.[7]

As someone who has always found the attractiveness of Camille Desmoulins both to his contemporaries and to historians very difficult to understand, I found this characterisation thought-provoking. In the novel, Desmoulins serves as critical go-between. Old school pal of Robespierre, intimate friend of Danton, Camille lubricates the Danton-Robespierre axis, and by doing so, highlights the extent to which Danton and Robespierre were similar rather than different (thus breaking the historiographical vulgate). The two men had grown up together, and grown close through their involvement in radical politics. They had different personalities and private lives; but they were peas in the same Revolutionary pod. Refreshingly, Mantel even allows Robespierre a sex life – and why not? Danton’s macho death-cell posturing, vaunting his own abundant sexual drive as against Robespierre’s alleged virginity have been followed far too uncritically by generations of historians. The break between the two men in Germinal Year II is not treated as an agenda-settling clash between two contrasting behemoths, let alone between two philosophies of Revolution, or between two contrasting political mindsets. The break came late and – Mantel has us believe – as a result of a clash within the private sphere not the public. (Over Danton’s alleged rape of one of the Duplay girls: no evidence, but no matter.) Not the least merit of Mantel’s extraordinary novel is to prompt us to break out of our fixation with the Danton-Robespierre polarity which has structured so much historical analysis of the Terror. A Place of Greater Safety calls on us as historians to re-boot our imaginations.

Hilary Mantel, A Place of Greater Safety, London, Viking: 1992; Picador USA: 2006 (749 pages); UK, Harper Collins/Fourth Estate, Reissue edition: 2010 (880 pages).

- I read the book in the Harper Perennial edition, published in 1997. It runs to 871 pages.

- Mantel has expressed “regret at not having been a historian,” in fact. See “An Interiew with Hilary Mantel,” edited by Rosario Arias, Atlantis, 20, 1998, 277-89: 89. Also worth consulting is Mantel’s article, “What a man is this with his crowd of women around him,” London Review of Books, 22 (30 March 2000), pp. 3-8.

- Cf. “a mob has no soul, no conscience; just paws and claws and teeth,” at p. 223.

- Significantly, the Saturn devouring his children expression is noted at p. 731 as “a pat phrase.”

- In the same spirit, one notes how Gérard Depardieu’s towerifng characterisation as the eponymous hero of Wajda’s Danton (1983), brilliantly set off against the ascetic figure of Wojciech Pzoniak as Robespierre, has probably done more to shape how historians nowadays think about the Terror than any recent history of the Terror.

- “An Interview,” p. 289.

- The phrase is used by Camille Desmoulins with this sense at p. 651.

I think this review does a fairly good job of highlighting the merits of a book I love but I have to disagree about the portrayal of the women – don’t see why they would seem any more flawed and unsympathetic than the men. This is a book where everyone is aweful and compelling and heart-breaking, even priggish Madame Rolande who certainly has her own kind of pathos and is hardly any more priggish than the male cast, who are all very vain and self-righteous in their own way. (Let’s be real – no one in this story lacked in the amour-propre department; it’s apparently a requirement for being a proper revolutionary).

Firstly, I don’t see what’s so particularly ghastly about Lucille – the way she jumps on the opportunity to marry Camille even though she knows he was orginally after her mom? It’s a bit ruthless, yes (in the way it’s bound to upset mom and dad), but that’s a given if you want to run with radicals. (Leading a mob to storm the bastille and voting to behead the King is going to upset mom and dad too). I see a woman who knows what she wants (and that’s not just Camille, obviously, but the chance to break free from her bourgeouise background – a fairly relateable desire, no?) And is in a way justified in this by the narrative – the marriage after all is portrayed as rather successful (if you disregard the whole getting beheaded bit in the end). She picked a man who suited her and she suited him and it might have all worked out just fine, if not for those meddling committees. Book-Lucille and Book-Camille might not be faithful to each other in the sexual sense, but that does not seem to strain their emotional connection – they “get” each other, can sometimes communicate without words and and show a great deal of affection towards each other to the end. Even in fiction, it’s rare to see a couple so well-matched.

Of course, Lucille gets more than she bargained for – just like Camille she got initially swept up in the romance of it all. Just like him, she has to see it through to the bitter end. But for the most part, she’s not wallowing in self-pity – she knows that this is what she signed up for, when she set her heart on Camille. (For me, a crucial scene is when she compares herself to Danton’s wife Gabrielle in that regard – “Gabrielle married a nice young lawyer; I married a revolutionary – I knew what I got myself into”, someting along those lines).

But I can see why someone wouldn’t be into Lucille. I guess if you can’t see the appeal of Camille, you probably won’t see the appeal of Lucille either.

What I don’t see at all is why anyone would describe Danton’s second wife Louise as dim-witted (or sweet, for the matter – she’s one of the few characters of Danton’s inner circle prepared to properly call him out on his bullsh*t on occassion). Girl’s 15, maybe cut her some slack? Do you really expect her to be able to go quite toe to toe with the towering intellects of her time at that age? And for a 15-year old, she’s rather precocious anyway. In the passages written from her POV it becomes very clear, that she’s much less naive than her surroundings believe her to be. She might not be entirely immune to the charms of Danton and Camille (neither was most of France, at some point in the story or another), but she also takes the measure of them, and for her purposes, maybe more accurately than many other characters in the novel. There’s a reason, why Camille – himself not always the most rigorous intellectual, maybe, but clearly graced with the occassionaly flash of brilliance – takes her absolutely serious as a rival when it comes to influencing Danton.

If there’s a character who could be described as dim-witted and sweet it’s probably Danton’s comparatively long-suffering first wife Gabrielle, and even she has her hidden depths and is quite a bit less clueless than the men in her life tend to give her credit for. It takes a really shallow reading to take Danton’s judgment of her at face value.

(More convincing candidates for “dim-witted and sweet” would be Louis Capet and the Philippe Egalité, as portrayed in this novel, although even in the fictional account, one could argue about the sweet part, I guess.)

Just read your excellent response to the review (after having seen the Wajda movie, read Mantel, and reread Carlyle). Mantel and Wajda seem to have used some of the same sources. Lots of little echoes in the film. In a couple of places, however, Mantel diverges from Carlyle. Both Jeanne Rolande and the ci-devant duc d’Orleans died very well (“Depechons-nous,” the latter says to Sansom; and Carlyle seems to have sources attesting to Philippe’s consistently noble demeanor in the hours preceding that polite suggestion)

Mantel’s portrayal of Mme. Rolande as a shallow, hypocritical groupie who uses her husband to force her way into a position of influence seems to have been an artifact of literary license. She (JR) was greatly respected in prison for her kindness to others and for her personal courage. When it was her turn, she was paired with a terrified man whose name I can’t recall. She told him she’d go first and show him how easy it was. Sansom wasn’t about to allow this because against the regs. Carlyle reports that Rolande responded that surely he wouldn’t deny a lady her last request. & he didn’t.

I can’t think of the name of the little neighbor girl who positions herself, perhaps not quite consciously, to become the second Mme. Danton, but the reviewer may have been influenced by the very young (12, rather than 15, she looked) actress who had the role in the film and says hardly two words.

Perhaps you haven’t seen the film. The Desmoulins’s parts were badly written, badly cast, and bizarrely directed. Camille doesn’t have long hair, isn’t good looking, and doesn’t seem to be very bright — the furthest thing in the world from Carlyle’s “lightly sparkling man” and Mantel’s lovable bundle of enigmas. He doesn’t read Augustine toward the end; he snivels. He petulantly refuses to talk to Robespierre twice. Lucile plays most of the film with a baby, whether she’s “helping” her husband with an article or coming apart as they take the prisoners away at the kangaroo court. She dresses plainly, with her hair tied in the back. Eleonore Duplay, otoh, is pretty and dresses in bright colors. Go figure.

I suspect that Mantel’s Danton is closer to the man than the one Wajda directed Depardieu as. But the director had only a little over 2 hours; the author had over 800 pages. The Polish actor who plays Robespierre, however, is superb, and pretty much as he was in the book.