Howard G. Brown

Binghamton University, SUNY

College courses on modern France often run from 1815 to sometime near the present. This suggests that Napoleon’s demise as emperor was the start of a new era. But the “Restoration” had begun more than a year earlier; therefore, 1815 better marks the end of a period than the beginning of one. And yet, the Hundred Days are incomprehensible without the social and political context of the early Restoration. This can be dull stuff compared to the swashbuckling return from Elba. Succor comes in the form of the film Le Colonel Chabert (1994) a brilliantly crafted exploration of uncertain identities, social climbing, and aristocratic snobbery set in the early years of the Restoration.

Yves Angelo’s film is based on a novella by Honoré de Balzac. The story first appeared in a magazine in 1832 and was later folded into La Comédie humaine in 1844. The eponymous protagonist, Colonel Chabert, was a derelict of the Napoleonic Empire. Despite humble beginnings in an orphanage, Chabert rose through the ranks during the Revolution and Empire by fighting in Napoleon’s campaigns in Italy, Egypt, Spain, and Russia. He reached the pinnacle of personal fame by leading a dangerous cavalry charge through the Russian lines at the battle of Eylau in February 1807. According to the Bulletin de la Grande Armée, Chabert’s heroic action turned the tide of battle, but got him killed in the process.

Yves Angelo’s film is based on a novella by Honoré de Balzac. The story first appeared in a magazine in 1832 and was later folded into La Comédie humaine in 1844. The eponymous protagonist, Colonel Chabert, was a derelict of the Napoleonic Empire. Despite humble beginnings in an orphanage, Chabert rose through the ranks during the Revolution and Empire by fighting in Napoleon’s campaigns in Italy, Egypt, Spain, and Russia. He reached the pinnacle of personal fame by leading a dangerous cavalry charge through the Russian lines at the battle of Eylau in February 1807. According to the Bulletin de la Grande Armée, Chabert’s heroic action turned the tide of battle, but got him killed in the process.

Who then was this decrepit drifter who appeared in Paris a decade later insisting that he was Colonel Chabert? His erstwhile wife, Rose Chapotel, a prostitute elevated to high society, considered the man an imposter seeking to claim her now considerable fortune and so, quite reasonably, refused to see him. But her solicitor, Maître Derville, was fascinated by the bizarre man, so much so that he was willing to pay the stranger’s living expenses long enough to determine whether his fantastic story was true. Derville learns that Colonel Chabert, in fact, had not died in battle. Rather, having been rendered cataleptic by a massive gash in his head and then buried alive in a common grave, the fallen warrior had managed to claw his way out in time to be rescued by Prussian peasants picking over the battlefield. A period of convalescence was followed by years as a penniless vagabond whose preposterous claims eventually landed him in a German mad house.

During Chabert’s prolonged travails, his “widow” had married a wealthy noble of ancient lineage, the Comte Ferraud, and bore him two children. The re-emergence of the old aristocracy after Napoleon’s defeat gave the recently minted Comtesse Ferraud an opportunity to consolidate her social position. Consequently, she had no desire to see Chabert come back from the dead. But Maître Derville, armed with all the legal evidence needed to enforce Chabert’s claims, astutely arranges a deal between the would-be dead man and his would-be widow. Unfortunately, greed on her side and passion on his destroy the carefully arranged transaction. The Comtesse Ferraud exploits her role as mother to convince Chabert to accept a far less generous settlement. Chabert accidentally overhears her scheming and so withdraws his consent. Her plan “suddenly afflicted him with an illness – disdain for humanity.” He abandons his efforts to restore his identity or reclaim his fortune. He thereby preserves his honor, but at the price of having to live out his final years anonymously in an asylum for the aged.

During Chabert’s prolonged travails, his “widow” had married a wealthy noble of ancient lineage, the Comte Ferraud, and bore him two children. The re-emergence of the old aristocracy after Napoleon’s defeat gave the recently minted Comtesse Ferraud an opportunity to consolidate her social position. Consequently, she had no desire to see Chabert come back from the dead. But Maître Derville, armed with all the legal evidence needed to enforce Chabert’s claims, astutely arranges a deal between the would-be dead man and his would-be widow. Unfortunately, greed on her side and passion on his destroy the carefully arranged transaction. The Comtesse Ferraud exploits her role as mother to convince Chabert to accept a far less generous settlement. Chabert accidentally overhears her scheming and so withdraws his consent. Her plan “suddenly afflicted him with an illness – disdain for humanity.” He abandons his efforts to restore his identity or reclaim his fortune. He thereby preserves his honor, but at the price of having to live out his final years anonymously in an asylum for the aged.

Balzac’s story is a gem of period commentary. Its characteristically vivid descriptions, whether of the paperasserie of a solicitor’s office or the squalor of an urban hovel, make it history by immersion. It also distills the quintessentially Balzacian critiques of human failing. These appear either in simple phrases – “tous trois le regardèrent avec une stupidité spirituelle” – or in sustained observations, such as Derville’s insistence that, of the three black-robed servants of society, the Priest, the Doctor, and the Lawyer, it is the latter who is most unhappy: “nos études sont des égouts qu’on peut pas curer.” It would be hard to find a more succinct, representative, and enjoyable embodiment of Balzac’s entire oeuvre than “Le Colonel Chabert.”

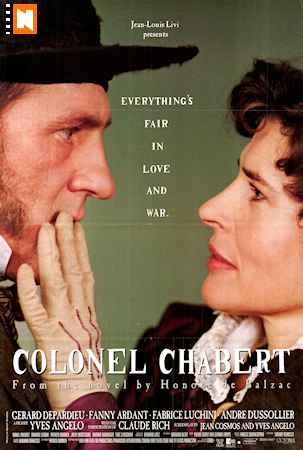

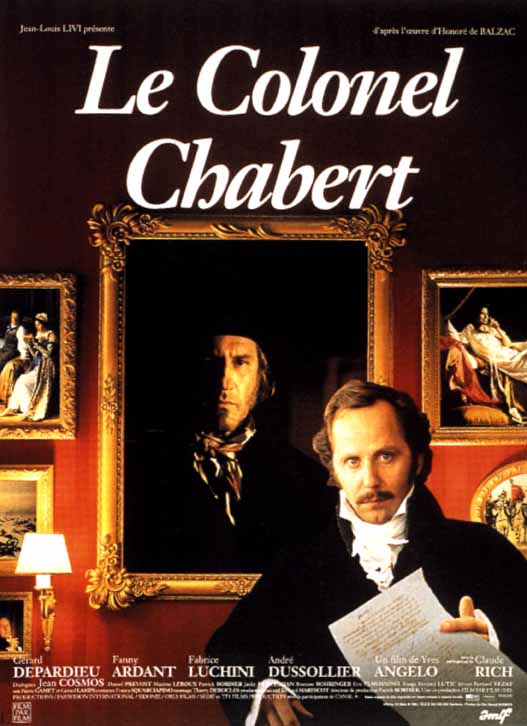

And yet the film is better – or at least more effective as an introduction to the Restoration. This is not only because film is a medium with which students are more comfortable. Nor is it due to the remarkable casting, though that too adds to its credibility. Gérard Depardieu as a wild-eyed and explosive Chabert has never performed better, not even as Pansette alias Martin Guerre. [1] Likewise, Fabrice Luchini magnificently incarnates the solicitor Derville. His crisply precise speech and piercing eyes combine perfectly to express fascination, intelligence and strategic acumen. Here is a man at the top of his profession, capable of discerning human motives without a hint of sentimentality. Finally, the compromised Comtesse Ferraud (formerly Madame Chabert) is played by Fanny Ardant, whose beautiful, angular face conveys both her continuing sexual allure and her hard attitude toward money. In short, the casting enhances the historical verisimilitude of the movie by not having to overcome the kind of physical or emotional anachronisms that undercut so many historical costume dramas. But the fact that Le Colonel Chabert is a movie, one that it is both sumptuously shot and perfectly cast, is not why it surpasses Balzac’s original story. Rather, the film proves more useful for teaching French history because it preserves most of the original novella, including detailed settings and clever dialogue, while adding lavish new scenes and elaborating on the characters.

And yet the film is better – or at least more effective as an introduction to the Restoration. This is not only because film is a medium with which students are more comfortable. Nor is it due to the remarkable casting, though that too adds to its credibility. Gérard Depardieu as a wild-eyed and explosive Chabert has never performed better, not even as Pansette alias Martin Guerre. [1] Likewise, Fabrice Luchini magnificently incarnates the solicitor Derville. His crisply precise speech and piercing eyes combine perfectly to express fascination, intelligence and strategic acumen. Here is a man at the top of his profession, capable of discerning human motives without a hint of sentimentality. Finally, the compromised Comtesse Ferraud (formerly Madame Chabert) is played by Fanny Ardant, whose beautiful, angular face conveys both her continuing sexual allure and her hard attitude toward money. In short, the casting enhances the historical verisimilitude of the movie by not having to overcome the kind of physical or emotional anachronisms that undercut so many historical costume dramas. But the fact that Le Colonel Chabert is a movie, one that it is both sumptuously shot and perfectly cast, is not why it surpasses Balzac’s original story. Rather, the film proves more useful for teaching French history because it preserves most of the original novella, including detailed settings and clever dialogue, while adding lavish new scenes and elaborating on the characters.

Each of these additional aspects of the film enhances its pedagogical power. The new scenes provide rich historical content. Whereas Balzac provides no description of the battle of Eylau, one of the bloodiest of the period,[2] the film opens with a prolonged sequence on its devastating aftermath. Carnage stretches as far as the camera can roam. All across the snowy landscape, human and animal corpses are being stripped or dragged, buried or burned. This is arguably the best evocation of the horrors of Napoleonic warfare available on film. Chabert’s memories justify several other flashbacks that add period texture. One impressively recreates the thrilling dangers of a mass cavalry charge and the brutal deaths that conclude it; another prowls through Chabert’s former home, panning slowly over the luxurious furniture, tapestries, carved banister, paintings, and objets d’art, then ends with a close-up of his beautiful wife. In passing, Chabert is shown donning his military uniform, a clear sign that we are contemplating the spoils of imperial adventure.

Several other additions serve to develop the characters and strengthen the plot. They also provide a better understanding of the social politics of the Restoration. By more fully developing the relationship between the Comte and Comtesse Ferraud, the film expertly captures the tension between the open elite fostered by Napoleon and the exclusionary elite constructed under Louis XVIII. The Comte is consumed by ambition to be elevated to the peerage. His strategy includes expanding his property into an entailed estate, but he can only do this by drawing on his wife’s fortune (i.e. Chabert’s booty wisely invested), which she is reluctant to permit. Moreover, the aristocratic power-brokers, former émigrés, insist that his wife’s association with the elite of the Empire is an obstacle to attaining the peerage, and he is advised to abandon her. Follow the example of Talleyrand, he is told, and cut her out surgically, then marry the daughter of an existing peer. Almost none of this can be found in the original novella, and yet all of it is perfectly in keeping with it. Balzac would approve.

Several other additions serve to develop the characters and strengthen the plot. They also provide a better understanding of the social politics of the Restoration. By more fully developing the relationship between the Comte and Comtesse Ferraud, the film expertly captures the tension between the open elite fostered by Napoleon and the exclusionary elite constructed under Louis XVIII. The Comte is consumed by ambition to be elevated to the peerage. His strategy includes expanding his property into an entailed estate, but he can only do this by drawing on his wife’s fortune (i.e. Chabert’s booty wisely invested), which she is reluctant to permit. Moreover, the aristocratic power-brokers, former émigrés, insist that his wife’s association with the elite of the Empire is an obstacle to attaining the peerage, and he is advised to abandon her. Follow the example of Talleyrand, he is told, and cut her out surgically, then marry the daughter of an existing peer. Almost none of this can be found in the original novella, and yet all of it is perfectly in keeping with it. Balzac would approve.

So too would Emmanuel Waresquiel, the foremost expert on the elites of the Restoration. He has persuasively argued that, in social terms, the regime “took the forms of a struggle for power and position … between the elites of the ‘former France’ and those of the ‘new France’ …. This clash revolved around the question of a necessary redefinition of the elites in light of the Revolution and Empire, between a ‘society of privilege’ and the ‘reign of merit and reason.’”[3] Derville embodies merit and reason and is highly successful professionally. Nonetheless, he is unable to reconcile the exemplars of Revolutionary and Napoleonic success (Chabert and his wife) because the Comtesse, when faced with the snobbery of aristocratic émigrés, concludes that preserving her family requires guarding her fortune. Her greed has harsh consequences. It leaves Chabert destitute and institutionalized, and it leaves her divorced and ostracized. Thus, by elaborating on the predicament and motives of the Comtesse, the film manages to replace Balzac’s rather crude deus ex machina with a resolution to the plot that anticipates the best recent scholarship on the period.

So too would Emmanuel Waresquiel, the foremost expert on the elites of the Restoration. He has persuasively argued that, in social terms, the regime “took the forms of a struggle for power and position … between the elites of the ‘former France’ and those of the ‘new France’ …. This clash revolved around the question of a necessary redefinition of the elites in light of the Revolution and Empire, between a ‘society of privilege’ and the ‘reign of merit and reason.’”[3] Derville embodies merit and reason and is highly successful professionally. Nonetheless, he is unable to reconcile the exemplars of Revolutionary and Napoleonic success (Chabert and his wife) because the Comtesse, when faced with the snobbery of aristocratic émigrés, concludes that preserving her family requires guarding her fortune. Her greed has harsh consequences. It leaves Chabert destitute and institutionalized, and it leaves her divorced and ostracized. Thus, by elaborating on the predicament and motives of the Comtesse, the film manages to replace Balzac’s rather crude deus ex machina with a resolution to the plot that anticipates the best recent scholarship on the period.

As we noted at the opening, the end of Napoleon and the start of the Restoration overlap, pointing both backwards and forwards. Yves Angelo’s film captures the Janus-faced nature of the period far better than Balzac’s novella on which it is based. Flashbacks provide exceptionally rich depictions of the Napoleonic Empire, be it on the battlefield or in the boudoir, and add depth to our understanding of the Restoration’s pampered elite and its neglect of the poor. Moreover, the rise of the professional class, the squalor of urban poverty, the sense of loss felt by military men after the defeat of Napoleon, and the triumph of greed over honor, are all drawn from Balzac but sharpened by a first-rate piece of historical cinema. Le Colonel Chabert has the power to make the Restoration interesting, whether as historical denouement or point of departure.

Honoré de Balzac, Le Colonel Chabert, préface et commentaires de Jeannine Guichardet (Paris: Presses Pocket, 1991).

Yves Angelo, Director, Le Colonel Chabert, 1994, Color, 110 min, France, Canal+, DD Productions, Film Par Film, Orly Films, Paravision International S.A., Sidonie, Sédif Productions, TFI films Production.

- It would be an interesting exercise to have students compare the mysteries of personal identity and social acceptance depicted in the two films.

- The Bulletin published in the Moniteur unusually described Eylau as a “massacre” and the battlefield as “a horror to see.” One French general noted that he “had never seen so many dead gathered on such a small patch of ground. Entire divisions, Russian and French, had been chopped to pieces where they fought … There was an enormous number of horses killed, which added to the bloody aspect of the tableau.” Quoted in Thierry Lentz, Nouvelle Histoire du Premier Empire, vol. 1 Napoléon et la conquête de l’Europe, 1804-1810 (Paris: Fayard, 2002), 275.

- L’Histoire à rebrousse-poil. Les élites, la Restauration, la Révolution. (Paris: Fayard, 2005), 12-13. This modest essay provides a synthetic introduction to his numerous other works on the period.