Alan Forrest

University of York

What, one may legitimately ask, can historians of war and conflict learn from novels, even great novels, when written by authors who did not take part in the conflict and may not have known those who did? The question is only complicated by the propagandist tone of so many of the memoirs and official histories that were published shortly after the end of wars. Yet to deny novels any role in the study of history is to discount the power of literary imagination in conjuring up the doubts and emotions of those who were there. Novelists often use their own experiences, like Tolstoy in War and Peace, to discuss the motives and pathologies of soldiers, and the crises of conscience and loyalty that they must have faced. Such portrayals offer healthy antidotes to the Great Man perspective of the generals and strategists, kings and emperors, by giving due place to the individual soldier, his fears and conflicting loyalties. Louis Aragon is, of course, a very different writer from Tolstoy, with different personal experiences and understanding of the past, albeit not as an army officer, like Tolstoy in the Crimea. But he did bring another, and many would argue, equally apposite experience, as a French patriot and communist who had lived through the crises of the Spanish Civil War and the German Occupation, which had necessitated choices that exposed the individual to mortal danger. His novel – published in 1958 – is about just such a moment, albeit one nearly 150 years into the past.

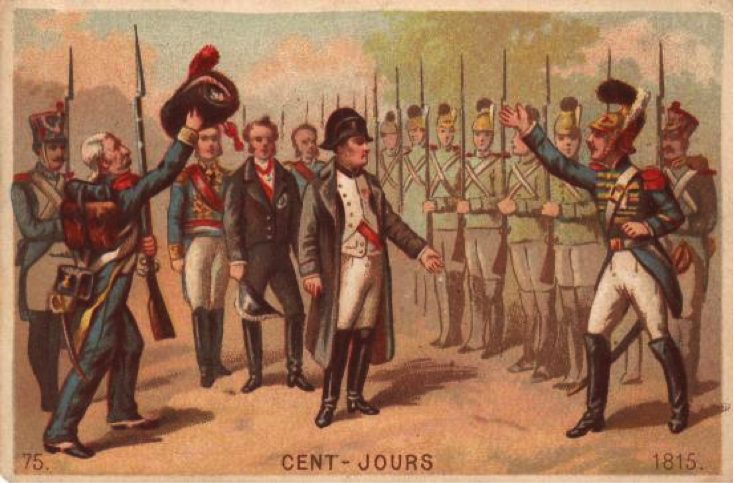

La Semaine Sainte, the Holy Week of the title, refers to the week of 19 to 26 March 1815, which coincided with Easter, following Napoleon’s escape from Elba and his landing on the French coast at Antibes. The story of his march north with his tiny force, avoiding the main roads, skirting around villages after nightfall, almost daring local mayors and National Guard units to bar his way, before charming his former marshals and their battalions to change sides and break their oaths to the King, went on to form part of the Napoleonic legend in the nineteenth century. It is often told as a story of stately progress, from Grenoble to Lyon, then up through Burgundy towards the capital, gathering support and swelling his army along the way. But, seen from the court in the Tuileries or from the officers’ mess of the regiments lining up to defend the King, the story was much more turbulent. Men who had previously been loyal to Napoleon, who had followed their Emperor to Borodino or Leipzig, now found themselves tugged between opposing loyalties, as the country divided into two clearly-defined camps. Louis XVIII, of course, hardly helped his cause by fleeing his capital for the Belgian frontier, arriving in Béthune amidst claims and counter-claims about his intentions and his proposed destination. Was he fleeing Paris to await a more propitious moment to re-impose his claims to his throne, possibly in Lille? Was he intending to cross the Channel and throw himself once more on the mercies of the British government? And what would the future hold for the French people if Napoleon recovered the throne? Would he now be, as he promised, a man of the people, loyal to the democratic traditions of the Revolution? Or would he simply plunge France once again into an endless series of wars, as his enemies proclaimed?

La Semaine Sainte, the Holy Week of the title, refers to the week of 19 to 26 March 1815, which coincided with Easter, following Napoleon’s escape from Elba and his landing on the French coast at Antibes. The story of his march north with his tiny force, avoiding the main roads, skirting around villages after nightfall, almost daring local mayors and National Guard units to bar his way, before charming his former marshals and their battalions to change sides and break their oaths to the King, went on to form part of the Napoleonic legend in the nineteenth century. It is often told as a story of stately progress, from Grenoble to Lyon, then up through Burgundy towards the capital, gathering support and swelling his army along the way. But, seen from the court in the Tuileries or from the officers’ mess of the regiments lining up to defend the King, the story was much more turbulent. Men who had previously been loyal to Napoleon, who had followed their Emperor to Borodino or Leipzig, now found themselves tugged between opposing loyalties, as the country divided into two clearly-defined camps. Louis XVIII, of course, hardly helped his cause by fleeing his capital for the Belgian frontier, arriving in Béthune amidst claims and counter-claims about his intentions and his proposed destination. Was he fleeing Paris to await a more propitious moment to re-impose his claims to his throne, possibly in Lille? Was he intending to cross the Channel and throw himself once more on the mercies of the British government? And what would the future hold for the French people if Napoleon recovered the throne? Would he now be, as he promised, a man of the people, loyal to the democratic traditions of the Revolution? Or would he simply plunge France once again into an endless series of wars, as his enemies proclaimed?

This placed the people of France in a considerable quandary. A war-weary nation faced the reality of renewed conflict and of renewed political division. It is perhaps Aragon’s greatest achievement to present that population in all its confused, at times contradictory, complexity to offer a panorama of opinions and reactions and the different experiences of that fateful week. He does not seek to offer a grand narrative or give a history lesson; Aragon’s surrealism would not admit of such a thing. Nor does he patronise ordinary men and women; Aragon is unrepentantly non-judgemental. Rather he examines the same events through different lenses, demonstrating their repercussions for the individuals involved and for society at large. In this way he makes his contribution to history from below.

This placed the people of France in a considerable quandary. A war-weary nation faced the reality of renewed conflict and of renewed political division. It is perhaps Aragon’s greatest achievement to present that population in all its confused, at times contradictory, complexity to offer a panorama of opinions and reactions and the different experiences of that fateful week. He does not seek to offer a grand narrative or give a history lesson; Aragon’s surrealism would not admit of such a thing. Nor does he patronise ordinary men and women; Aragon is unrepentantly non-judgemental. Rather he examines the same events through different lenses, demonstrating their repercussions for the individuals involved and for society at large. In this way he makes his contribution to history from below.

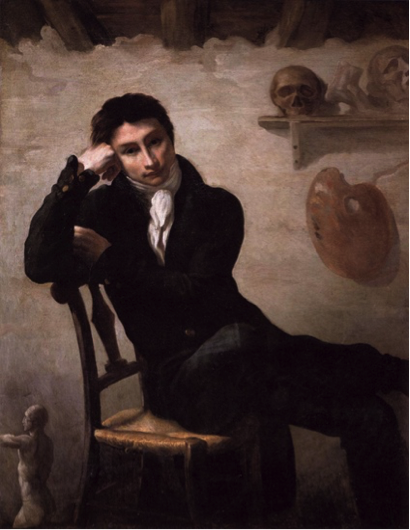

Most civilians could afford to wait and see. It was the army that, most immediately, had to decide where their future loyalties lay, an army that had served the Empire but which had now taken an oath to serve the Bourbons. Officers, in particular, had no option but to decide: to respond to the King’s call, or to defect to the Usurper. Aragon’s novel tracks different officers through the events of the week, but his main focus is on one royal officer, a young man with a singular future ahead of him: the painter Théodore Géricault, whose thoughts and dilemmas he relates. Which France did he want – a return to privilege and Catholicism with the Bourbons, or the hopes and aspirations the Emperor evoked? And whom would he betray? Which cause, which ideas, but also, far more personally than that, which friends, which comrades-in-arms? Everyone, it seemed in this post-revolutionary world, had a past. Aragon introduces us to diehard royalists, men newly back from emigration, still seeking to avenge victims of the Terror of 1794; a local National Guard unit commanded by a former Babouviste; and many who, as republicans, did not really know what to think of Napoleon. For his own part Géricault, as an artist, cannot avoid being grateful to the man who had brought the treasures of Rome and Florence to the Louvre, but is faced with a stark choice. Davout, the new Minister of War, has ordered the King’s arrest, and Géricault must show his true colours. Is his loyalty to the King, or to the patrie? The option of serving any master, indiscriminately, had suddenly become untenable.

Many of these young men did not know what they believed or what ideology they wanted to live by. 1815, as Pierre Serna has remarked, was a time of indecision when many quietly changed sides. In the armies Aragon finds many who fit this description; this was “la France des girouettes.” They were soldiers seeking a career in the only profession they knew, at a time when just continuing in service could involve political compromises. Friends were divided, and army units ended up shooting at those they had fought alongside, men just like themselves. In this confused, chaotic, rain-sodden week they understandably made different calculations and different choices. In Géricault’s own case, the decision to remain loyal to the Bourbons was born of circumstance. In the rain at Saint-Denis he had seen the king, looking pained and pitiful, and he vowed to remain with him; when chosen to escort the royal berline, he had made up his mind. But it came only after several nights of agonizing indecision. The dominant image of the flight from the capital is of torrents of rain, clawing mud, poor communications, and utter confusion with army units losing their way in Paris’s own backyard. They had, after all, spent much of their young lives beyond France’s boundaries. For men of his generation, remarks Aragon, the map of Europe was more familiar than the landscape of the Île-de-France. Their world was the army, and he is especially good at describing the internal politics of the army, any army, but especially one that had been tossed back and forwards by political upheaval. Of course they were on their guard for signs of disorder and insurrection in Paris, ready to intervene at the slightest sign of trouble. But other aspects of military life merely added to the confusion: the personal jealousies, the gossip and bickering, or the endless jostling for promotions that so characterised this masculine culture. To these were added the risks they were now forced to take: of taking a wrong turn, supporting the wrong side, committing involuntary acts of treason and facing a military tribunal, or even a humiliating death.

Many of these young men did not know what they believed or what ideology they wanted to live by. 1815, as Pierre Serna has remarked, was a time of indecision when many quietly changed sides. In the armies Aragon finds many who fit this description; this was “la France des girouettes.” They were soldiers seeking a career in the only profession they knew, at a time when just continuing in service could involve political compromises. Friends were divided, and army units ended up shooting at those they had fought alongside, men just like themselves. In this confused, chaotic, rain-sodden week they understandably made different calculations and different choices. In Géricault’s own case, the decision to remain loyal to the Bourbons was born of circumstance. In the rain at Saint-Denis he had seen the king, looking pained and pitiful, and he vowed to remain with him; when chosen to escort the royal berline, he had made up his mind. But it came only after several nights of agonizing indecision. The dominant image of the flight from the capital is of torrents of rain, clawing mud, poor communications, and utter confusion with army units losing their way in Paris’s own backyard. They had, after all, spent much of their young lives beyond France’s boundaries. For men of his generation, remarks Aragon, the map of Europe was more familiar than the landscape of the Île-de-France. Their world was the army, and he is especially good at describing the internal politics of the army, any army, but especially one that had been tossed back and forwards by political upheaval. Of course they were on their guard for signs of disorder and insurrection in Paris, ready to intervene at the slightest sign of trouble. But other aspects of military life merely added to the confusion: the personal jealousies, the gossip and bickering, or the endless jostling for promotions that so characterised this masculine culture. To these were added the risks they were now forced to take: of taking a wrong turn, supporting the wrong side, committing involuntary acts of treason and facing a military tribunal, or even a humiliating death.

These are, of course, the symptoms of a society in the midst of political and social convulsion, where no one can confidently read the future and where soldiers bore a particular burden of risk. The week of 19 March saw France on the brink of civil war, the self-destructive urges of the Revolutionary era ready to reignite as Napoleon returned from exile. Emotions ran high, and Aragon paints a picture of a people seized by fear, hope and despair in equal measure, through the prism of a young officer exposed for the first time to the deprivations of a forced march. Géricault is depicted as a man of tender feelings, a vulnerable young man caught up in the contradictions of his times; he is the sensitive artist that he will be in civilian life, not some heartless cog in a military machine. At times he reflects on the futility of the political quarrels that surround him, concluding that his future in this cruel century lies not in the army. “Later, perhaps,” he muses, “when men have ended quarrels for which I can find little passion, later, I will paint, that’s all.” Monarchy and empire, Louis XVIII and Napoleon, have sunk into insignificance. France is more important than these; and France, for Géricault as for Aragon himself, merges with its people, its struggling masses, le peuple.

These are, of course, the symptoms of a society in the midst of political and social convulsion, where no one can confidently read the future and where soldiers bore a particular burden of risk. The week of 19 March saw France on the brink of civil war, the self-destructive urges of the Revolutionary era ready to reignite as Napoleon returned from exile. Emotions ran high, and Aragon paints a picture of a people seized by fear, hope and despair in equal measure, through the prism of a young officer exposed for the first time to the deprivations of a forced march. Géricault is depicted as a man of tender feelings, a vulnerable young man caught up in the contradictions of his times; he is the sensitive artist that he will be in civilian life, not some heartless cog in a military machine. At times he reflects on the futility of the political quarrels that surround him, concluding that his future in this cruel century lies not in the army. “Later, perhaps,” he muses, “when men have ended quarrels for which I can find little passion, later, I will paint, that’s all.” Monarchy and empire, Louis XVIII and Napoleon, have sunk into insignificance. France is more important than these; and France, for Géricault as for Aragon himself, merges with its people, its struggling masses, le peuple.

La Semaine Sainte has been hailed by critics as Aragon’s masterpiece for its broad canvas of a society plunged once more into confusion a year after the Restoration settlement. Through individuals caught in the same event, he reflects on the army, and through the army on French society itself. He draws parallels with other periods of crisis when individuals had to make choices, at times obliquely, but the parallels are there for all to see. The Occupation in 1940 is the most obvious, when individuals found themselves trapped by events beyond their control. Aragon warns against confusing two very different contexts –we are talking about the same countryside engulfed once again in a chaotic retreat – but the soldier of 1940 does not have the mentality of a soldier of 1815, because the contradictions of the one are not the contradictions of the other, because words and their meaning had changed from one period to another. Yet there are significant similarities, too. Aragon understands human motivations and morale, and he knows that, in the early nineteenth century as in the mid- twentieth, ideologies and national politics have only so much persuasive power. Individuals are as much influenced by bonds of friendship and comradeship as they are by political affiliations or ideological commitments. What he describes amidst the chaos of these few days is what he had witnessed around him, in the PCF in Paris in the 1930s, in the Communist Resistance after 1940 – a largely self-contained world peopled by comrades and copains with whom you shared your leisure hours, discussed your dreams for the future, and spent your Sundays selling L’Huma-Dimanche at the nearest bouchon de métro. They were people you passed your youth with, whose commitment you shared and whose companionship kept you afloat. A Communist of that era understood the full meaning of fraternité. Aragon had difficult, fateful decisions to make in his own lifetime. And vividly, sensitively, acutely, he recreates that uncertainty, that conflict of interests and emotions, in the characters he brings to life in the first week of the Hundred Days in the pages of La Semaine Sainte.

La Semaine Sainte has been hailed by critics as Aragon’s masterpiece for its broad canvas of a society plunged once more into confusion a year after the Restoration settlement. Through individuals caught in the same event, he reflects on the army, and through the army on French society itself. He draws parallels with other periods of crisis when individuals had to make choices, at times obliquely, but the parallels are there for all to see. The Occupation in 1940 is the most obvious, when individuals found themselves trapped by events beyond their control. Aragon warns against confusing two very different contexts –we are talking about the same countryside engulfed once again in a chaotic retreat – but the soldier of 1940 does not have the mentality of a soldier of 1815, because the contradictions of the one are not the contradictions of the other, because words and their meaning had changed from one period to another. Yet there are significant similarities, too. Aragon understands human motivations and morale, and he knows that, in the early nineteenth century as in the mid- twentieth, ideologies and national politics have only so much persuasive power. Individuals are as much influenced by bonds of friendship and comradeship as they are by political affiliations or ideological commitments. What he describes amidst the chaos of these few days is what he had witnessed around him, in the PCF in Paris in the 1930s, in the Communist Resistance after 1940 – a largely self-contained world peopled by comrades and copains with whom you shared your leisure hours, discussed your dreams for the future, and spent your Sundays selling L’Huma-Dimanche at the nearest bouchon de métro. They were people you passed your youth with, whose commitment you shared and whose companionship kept you afloat. A Communist of that era understood the full meaning of fraternité. Aragon had difficult, fateful decisions to make in his own lifetime. And vividly, sensitively, acutely, he recreates that uncertainty, that conflict of interests and emotions, in the characters he brings to life in the first week of the Hundred Days in the pages of La Semaine Sainte.

Louis Aragon, La Semaine Sainte, Paris: Gallimard, 1958, English translation Holy Week, London: Hamish Hamilton, 1961.