Howard G. Brown

Binghamton University, SUNY

The original title of the epic silent film, Napoléon, vu par Abel Gance, provides the basis for understanding its pedagogical powers. The film is an idiosyncratic interpretation of both Napoleon and the French Revolution, one that only a creative genius like Abel Gance could pull off. Despite its abundance of glaring errors, distortions, and reworkings of the historical record, the film manages to present key aspects of the period in ways that deserve to be called historical truth. Thus, the challenge of using this film for teaching college-level history lies less in its combination of enormous length and antiquated format than in its powerful mix of historical realism and blatant myth-making.

Abel Gance began his film as the first of a planned series of six films to cover the full life of Napoleon Bonaparte. However, his maniacal overspending on the first episode yielded an astronomical and unprecedented amount of footage, much of it devoted to extended subplots that had to be eliminated in order to make the film even remotely commercially viable. As it stands, the film begins with the young Corsican pupil “Paille-au-nez” Buonaparte at the French military prep school at Brienne where loneliness, mockery and bullying gave him character and leadership skills. No attempt is made to cover his training as an artillery officer, which would have suggested that he was not an entirely self-made man. Other lengthy sequences include his involvement in Corsican politics in the early Revolution, where he emerges as a fierce French patriot and great hope of the Bonaparte family. Much time is devoted to the French Revolution, covering major events from the overthrow of the Monarchy in 1792, through the Terror, the Thermidorian period, and into the early Directory. At times, Bonaparte is little more than an iconic walk-on blessed with a penetrating insight into the historical significance of current events. The romance with Joséphine also receives extended treatment. Here Bonaparte is depicted as naïve and pathetic, the opposite of the rakish and dissolute nobility of the ancien régime as embodied by Barras. Having spent much time establishing Bonaparte as the victor of both the siege of Toulon in 1793 and the Vendémiaire uprising of 1795, Gance then ends the film with the earliest victories won by the Army of Italy under his command in 1796. Emotional intensity and grandiosity suffuse the film throughout, making it clear that this would be a crowd-pleasing block-buster with a sustained argument – Napoleon was the savior of France. Who knows whether any nuance would ever have been introduced by episodes three, four, and five, when dictatorship and defeat could hardly have been written out of the story.

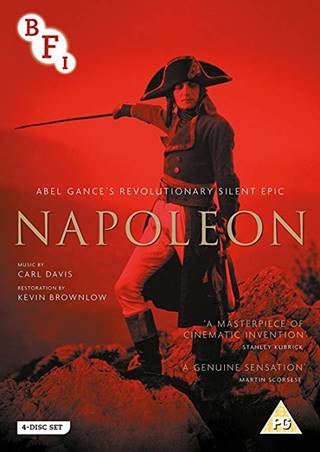

The original masterpiece was made in 1925-26, just before “talkies” transformed cinema, and so depended on intertitles for vital information and minimal dialogue. It also required a live orchestra to provide appropriate mood-setting music. Ninety years later, the spectacular reconstruction and restoration of the film by Kevin Brownlow and the British Film Institute, along with the brilliant score by Carl Davis, offers a viewing experience that even the Hunger Games generation can appreciate. Of course, such herculean efforts would not have been undertaken if the original film had not been replete with cinematic ingenuity, striking settings, huge crowds of extras, and inimitable individual performances, all seasoned with authentic period costumes, clever details, and even comic relief. This latest version may not be the definitive version of the film Napoleon (there are rumors that a French version is in the offing) but it is easily the most complete and most exciting version yet made. In fact, so powerful and appealing is this new version that showing it to students runs the risk of having Gance’s interpretation indelibly imprinted on them, even in an age of Twitter-shaped attention spans and “fake news” skepticism. To avoid such an ahistorical outcome, it is necessary to appreciate the film as an extraordinary work of art rather than an elaborate recreation of the past.

The BFI’s 2016 version of Napoleon lasts five hours and thirty-two minutes. This is considerably longer than the 1981 version sponsored by the Hollywood director, Francis Ford Coppola and released on VHS by Zoetrope Studios, which runs to a little less than four hours. The additional hour and a half is the result of two things that significantly improve the overall film: 1) changing the speed from 24 feet per second (as required by standard projectors) to the more appropriate 20 feet per second (made possible by digitization), thereby removing much of the jerkiness and excessive speed associated with silent films (and present in the US version by Coppola); 2) including previously missing footage in many scenes. Each of these adds about 45 minutes to the overall running time. The additional footage is by no means all of the missing film [1]. Making multiple, often shorter, versions of the film together with prolonged neglect and disastrous fires at the Cinémathèque française have left significant gaps, as Gance’s 1927 scenario indicates. This can be confusing at times. The prolonged section about the siege of Toulon in 1793, for example, is missing the sequence in which Bonaparte leads an unsuccessful charge by new, untrained infantrymen and a hundred cavalry against the English batteries of “Little Gibraltar.” Nonetheless, an intertitle provides a remark from Salicetti, the Convention’s deputy on mission, condemning Bonaparte’s charge as a great crime and worthy of beheading. Footage of another attack that results in Bonaparte’s only major wound, a bayonet to the thigh, is also missing. As a result, a meeting of the army’s leadership, including Bonaparte, is followed by an incoherent intertitle describing his fearlessness in battle: “He is in the thick of fire, in his element.” On the other hand, the additional footage provides more continuity for Tristan Fleuri, a fictional character who represents the French everyman. As such, his repeated appearance, each time in a new function – scullion, tavern keeper, soldier – conveys Bonaparte’s popular appeal as well as his (imagined) refusal to act the populist.

The BFI’s 2016 version of Napoleon lasts five hours and thirty-two minutes. This is considerably longer than the 1981 version sponsored by the Hollywood director, Francis Ford Coppola and released on VHS by Zoetrope Studios, which runs to a little less than four hours. The additional hour and a half is the result of two things that significantly improve the overall film: 1) changing the speed from 24 feet per second (as required by standard projectors) to the more appropriate 20 feet per second (made possible by digitization), thereby removing much of the jerkiness and excessive speed associated with silent films (and present in the US version by Coppola); 2) including previously missing footage in many scenes. Each of these adds about 45 minutes to the overall running time. The additional footage is by no means all of the missing film [1]. Making multiple, often shorter, versions of the film together with prolonged neglect and disastrous fires at the Cinémathèque française have left significant gaps, as Gance’s 1927 scenario indicates. This can be confusing at times. The prolonged section about the siege of Toulon in 1793, for example, is missing the sequence in which Bonaparte leads an unsuccessful charge by new, untrained infantrymen and a hundred cavalry against the English batteries of “Little Gibraltar.” Nonetheless, an intertitle provides a remark from Salicetti, the Convention’s deputy on mission, condemning Bonaparte’s charge as a great crime and worthy of beheading. Footage of another attack that results in Bonaparte’s only major wound, a bayonet to the thigh, is also missing. As a result, a meeting of the army’s leadership, including Bonaparte, is followed by an incoherent intertitle describing his fearlessness in battle: “He is in the thick of fire, in his element.” On the other hand, the additional footage provides more continuity for Tristan Fleuri, a fictional character who represents the French everyman. As such, his repeated appearance, each time in a new function – scullion, tavern keeper, soldier – conveys Bonaparte’s popular appeal as well as his (imagined) refusal to act the populist.

The monumental length of Napoleon presents major pedagogical challenges. Of course, a few short excerpts can always be chosen for classroom use. Favorites would include scenes of the National Convention, especially the “double storm” in which Bonaparte’s flight from Corsica in a small boat is intercut with the tumultuous expulsion of the Girondins, filmed with a swinging overhead camera that swooped low enough to frighten the extras. The session of 9 Thermidor is also filmed with a wonderful summary of the humanitarian intentions of the Revolution, articulated to the Convention by Saint Just (played effeminately by Abel Gance himself), followed by a riotous arrest of the Robespierrists in which many extras were physically injured.

The monumental length of Napoleon presents major pedagogical challenges. Of course, a few short excerpts can always be chosen for classroom use. Favorites would include scenes of the National Convention, especially the “double storm” in which Bonaparte’s flight from Corsica in a small boat is intercut with the tumultuous expulsion of the Girondins, filmed with a swinging overhead camera that swooped low enough to frighten the extras. The session of 9 Thermidor is also filmed with a wonderful summary of the humanitarian intentions of the Revolution, articulated to the Convention by Saint Just (played effeminately by Abel Gance himself), followed by a riotous arrest of the Robespierrists in which many extras were physically injured.  The scene in the Cordelier Club, with its wide range of male and female social types, provides a good sense of revolutionary fervor, even if it is not where the Marseillaise made its Parisian début. Likewise, the eerily filmed lynching that takes place outside Bonaparte’s apartment window offers a visceral sense of popular violence. Other gems include the famous snowball fight at Brienne, where dividing the screen into four and then nine segments creates a crescendo of furious fighting.

The scene in the Cordelier Club, with its wide range of male and female social types, provides a good sense of revolutionary fervor, even if it is not where the Marseillaise made its Parisian début. Likewise, the eerily filmed lynching that takes place outside Bonaparte’s apartment window offers a visceral sense of popular violence. Other gems include the famous snowball fight at Brienne, where dividing the screen into four and then nine segments creates a crescendo of furious fighting.

And, of course, there is the grand finale, the famous triptych of Bonaparte mustering the Army of Italy and leading it into battle at Montenotte and Montezemolo. This Polyvision, as it was dubbed, was originally reserved for venues that could accommodate three full movie screens. An alternative version for a single screen is available, but the grandeur of the triptych, even when compressed to a rather narrow band across a single screen, is much superior. Moreover, showing the triptych demonstrates Gance’s innovative genius better than any careful discussion of tracking shots, chest-mounted cameras, multiple exposures of the same strip of celluloid, or a studio-simulated hailstorm could ever do.

There are two other basic strategies for using Napoleon for teaching purposes, although both require showing it outside of the classroom. It can either be shown in its enormous entirety as a special event, probably for extra credit, or made into a reasonable viewing assignment by reducing it to a selection of scenes that might total the length of a regular feature film, say about two hours’ worth [2]. This latter choice has proven highly successful in my junior-level course on the French Revolution and Napoleonic France. Truncating the film in this way allows it to become part of a regular series of films that are required viewing outside of class time and that supplement specialized readings for the course. In either case, selecting episodes from the film that convey Gance’s interpretation of the relationship between the French Revolution and Napoleon focuses attention on the most important, as well as the most historically subversive, elements of this great classic.

There are two other basic strategies for using Napoleon for teaching purposes, although both require showing it outside of the classroom. It can either be shown in its enormous entirety as a special event, probably for extra credit, or made into a reasonable viewing assignment by reducing it to a selection of scenes that might total the length of a regular feature film, say about two hours’ worth [2]. This latter choice has proven highly successful in my junior-level course on the French Revolution and Napoleonic France. Truncating the film in this way allows it to become part of a regular series of films that are required viewing outside of class time and that supplement specialized readings for the course. In either case, selecting episodes from the film that convey Gance’s interpretation of the relationship between the French Revolution and Napoleon focuses attention on the most important, as well as the most historically subversive, elements of this great classic.

Gance presents Napoleon as a self-made hero and the embodiment of French national greatness. In order to make his effort more credible, Gance inserts numerous narrative intertitles that include the word “Historical” in parentheses at the bottom. These frequently obscure the extent to which Gance aggressively alters established facts and events. For example, Saliceti is presented as an opponent and threat to Bonaparte throughout the siege of Toulon, whereas, in fact, he had used his authority to appoint and promote his fellow Corsican to command the artillery there. Gance’s version spares Bonaparte from the perceived taint of Jacobinism. Likewise, following his success at Toulon, Gance has Bonaparte turn down an offer from Robespierre to command the National Guard in Paris because Bonaparte “did not want to support a man like [him].” This leads Robespierre to acquiesce to a request from Saliceti to have Bonaparte imprisoned. All of this is nonsense, of course: Bonaparte was briefly arrested, but only after 9 Thermidor and because he was a known protegé of both Saliceti and Augustin Robespierre, not their opponent. Similar liberties are taken with Bonaparte’s role in suppressing the Vendémiaire uprising, which Gance presents as “a few insignificant skirmishes” even though it was the second bloodiest day of the Revolution in Paris thanks to Bonaparte’s willingness to use cannon to break the insurgents.

Such significant alterations to the historical record are the fruit of Gance’s strongly negative presentation of the French Revolution. As suggested earlier, his depictions of raucous sessions in the Convention and mob violence in the streets are powerful evocations that help to convey the origins of the Terror. So too are the memorable scenes showing the arbitrariness that characterized both its bureaucracy and the selection of prisoners for execution. However, Gance presents Marat as obviously mad, Danton as almost hysterical, Robespierre as sinister and aloof, and Couthon as simply creepy. Ordinary revolutionaries may wear tophats, woolen caps, or female bonnets, but they are all clearly prone to emotional instability. The melodramatic elements of these characterizations do not destroy their ability to influence audiences, perhaps because they are woven into many convincingly realistic images. Throughout the film, the ravages of poverty are effectively manifest in tattered clothing and disheveled hair. Crowded street scenes and dilapidated buildings also contrast sharply with panoramic vistas on Corsica or in the foothills of the Alps. This recreation of people in historic place and time remains an enduring strength of the film.

Such significant alterations to the historical record are the fruit of Gance’s strongly negative presentation of the French Revolution. As suggested earlier, his depictions of raucous sessions in the Convention and mob violence in the streets are powerful evocations that help to convey the origins of the Terror. So too are the memorable scenes showing the arbitrariness that characterized both its bureaucracy and the selection of prisoners for execution. However, Gance presents Marat as obviously mad, Danton as almost hysterical, Robespierre as sinister and aloof, and Couthon as simply creepy. Ordinary revolutionaries may wear tophats, woolen caps, or female bonnets, but they are all clearly prone to emotional instability. The melodramatic elements of these characterizations do not destroy their ability to influence audiences, perhaps because they are woven into many convincingly realistic images. Throughout the film, the ravages of poverty are effectively manifest in tattered clothing and disheveled hair. Crowded street scenes and dilapidated buildings also contrast sharply with panoramic vistas on Corsica or in the foothills of the Alps. This recreation of people in historic place and time remains an enduring strength of the film.

In contrast to the violence and volatility of revolutionary politics, Napoleon is presented as singularly decisive and resolute. Gance unforgettably associates the young Napoleon with a pet eagle at Brienne and then turns it into the living symbol of a mighty destiny. Of course, this glorious future is only made possible by Bonaparte’s success as an army officer.

In contrast to the violence and volatility of revolutionary politics, Napoleon is presented as singularly decisive and resolute. Gance unforgettably associates the young Napoleon with a pet eagle at Brienne and then turns it into the living symbol of a mighty destiny. Of course, this glorious future is only made possible by Bonaparte’s success as an army officer.

But Gance does not glorify war. On the contrary, viewers usually wince as they watch a cannon being rolled over a wounded soldier’s leg. They also see dying men buried in mud, observe appalling human carnage after the taking of Toulon, and witness the arduous life of soldiers, whether in close combat, at bivouac, or on campaign. Presiding over all of this – stepping over corpses, surveying the ghosts of the Convention, and galloping past marching infantry – is the slight man in the bicorn hat. Albert Dieudonné’s incarnation of Napoleon has never been superseded. His fierce and commanding stare, usually delivered with his hands behind his back, embodies the essence of Bonaparte’s authoritarian charisma. Equally, Dieudonné’s warm smile renders Bonaparte simpatico in domestic settings. The combined effect turns an ordinary man into a pillar of determination, heroically saving France from the demons of revolution. With Mussolini in power and Hitler on the rise at the time, it is easy to understand why some critics decried Napoleon, vu par Abel Gance as a boon to nascent fascists in France. Thus, the anti-historical qualities and political bias of the film are of one piece. [3]

But Gance does not glorify war. On the contrary, viewers usually wince as they watch a cannon being rolled over a wounded soldier’s leg. They also see dying men buried in mud, observe appalling human carnage after the taking of Toulon, and witness the arduous life of soldiers, whether in close combat, at bivouac, or on campaign. Presiding over all of this – stepping over corpses, surveying the ghosts of the Convention, and galloping past marching infantry – is the slight man in the bicorn hat. Albert Dieudonné’s incarnation of Napoleon has never been superseded. His fierce and commanding stare, usually delivered with his hands behind his back, embodies the essence of Bonaparte’s authoritarian charisma. Equally, Dieudonné’s warm smile renders Bonaparte simpatico in domestic settings. The combined effect turns an ordinary man into a pillar of determination, heroically saving France from the demons of revolution. With Mussolini in power and Hitler on the rise at the time, it is easy to understand why some critics decried Napoleon, vu par Abel Gance as a boon to nascent fascists in France. Thus, the anti-historical qualities and political bias of the film are of one piece. [3]

Film critics have long looked past these flaws in favor of appreciating Gance’s extraordinary technical creativity and narrative sophistication. It is in this spirit that the new version was completed. Kevin Brownlow’s decades of obsessive commitment to restoring Napoleon inspired the British Film Institute to take up his mantle by employing the London-based Dragon to undertake a complete digital restoration. This process involved removing dirt and scratches from some 50 million digitally-scanned frames. Reconstituting the original chemicals used for tinting and toning 1920s celluloid provided the basis for coloring the new images. Furthermore, color correction and consistency, especially in terms of low lights and high lights, together with stabilizing the picture frame, provide a remarkably clear and smooth moving image. The result is spectacular. In many scenes, black and white gives way to monochromatic coloration – soft magenta, blazing red, marine blue, sepia yellow, etc. Gance’s use of color greatly sharpens the difference between interior and exterior scenes. Color also intensifies the action sequences. No less important is the addition of an astonishing symphonic score composed and conducted by Carl Davis (soundtrack in PCM 2.0 stereo). On the “extras” feature of the DVD set, Davis explains his compositional process. This involved borrowing music from “all the good guys – Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven” as well as lesser known composers of the period, together with revolutionary songs, notably the “Chant du départ,” “Ça ira,” and “Carmagnole,” as well as various Corsican folk songs. Davis also composed a number of original themes. The one associated with the eagle has the air of a masterpiece by John Williams. The result is definitely superior to the already very impressive score by Carmine Coppola (Francis’s father) used for the US version of 1981 [4]. Being “literal” to what appears on screen also requires the frequent use of snare drums and even the bizarre playing of a hurdy-gurdy during a meeting of the Committee of Public Safety.

Film critics have long looked past these flaws in favor of appreciating Gance’s extraordinary technical creativity and narrative sophistication. It is in this spirit that the new version was completed. Kevin Brownlow’s decades of obsessive commitment to restoring Napoleon inspired the British Film Institute to take up his mantle by employing the London-based Dragon to undertake a complete digital restoration. This process involved removing dirt and scratches from some 50 million digitally-scanned frames. Reconstituting the original chemicals used for tinting and toning 1920s celluloid provided the basis for coloring the new images. Furthermore, color correction and consistency, especially in terms of low lights and high lights, together with stabilizing the picture frame, provide a remarkably clear and smooth moving image. The result is spectacular. In many scenes, black and white gives way to monochromatic coloration – soft magenta, blazing red, marine blue, sepia yellow, etc. Gance’s use of color greatly sharpens the difference between interior and exterior scenes. Color also intensifies the action sequences. No less important is the addition of an astonishing symphonic score composed and conducted by Carl Davis (soundtrack in PCM 2.0 stereo). On the “extras” feature of the DVD set, Davis explains his compositional process. This involved borrowing music from “all the good guys – Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven” as well as lesser known composers of the period, together with revolutionary songs, notably the “Chant du départ,” “Ça ira,” and “Carmagnole,” as well as various Corsican folk songs. Davis also composed a number of original themes. The one associated with the eagle has the air of a masterpiece by John Williams. The result is definitely superior to the already very impressive score by Carmine Coppola (Francis’s father) used for the US version of 1981 [4]. Being “literal” to what appears on screen also requires the frequent use of snare drums and even the bizarre playing of a hurdy-gurdy during a meeting of the Committee of Public Safety.

The combination of Gance’s original genius, Kevin Brownlow’s passionate reconstruction, BFI and Dragon’s twenty-first century restoration, and Carl Davis’ ingenious score makes the 2016 version of Napoleon mesmerizing and well-worth showing to students, whether in whole or in part. However, it is only by instructing students in the film as a work of art that it can also become an effective tool in teaching history. Although many “alternative facts” – some stamped “(Historical)” by intertitles – need to be corrected, a classroom discussion of Napoleon should enhance an understanding of history as not merely “what actually happened,” but as an essentially interpretive discipline always intimately linked to its time and place of production.

Abel Gance’s Revolutionary Silent Epic Napoleon, music by Carl Davis, restoration by Kevin Brownlow. 4-disc set. London: British Film Institute, 2016.

France/1927/black and white, tinted and toned/silent with English intertitles/332 minutes/original aspect ratios1.33:1 + 4:1 (triptych)

NOTES

- The “full version” (dubbed the version définitive) shown at the Apollo in Paris in 1927 lasted nine hours over two days. Even the “editor’s cut” sent to M-G-M in 1928 ran to six and a half hours. Kevin Brownlow, Napoleon: Abel Gance’s Classic Film, new edition (London: Photoplay, 2004), 146, 282. Pages 271-72 list nineteen versions of the film!

- Fascinating as the following elements are in terms of film making, I choose not to show anything that happened on Corsica, any scenes related to Joséphine (including the truly ahistorical “victims ball”), or the early sections of the snowball fight, the siege of Toulon, and mustering the Army of Italy, all of which are very long scenes.

- Having students also view Jean Renoir’s Marseillaise (1937), funded in part by the Front populaire, helps to balance the interpretive scales, both in favor of the Revolution and in favor of its complexity.

- The original 1927 music had been composed by Arthur Honegger and then lost for decades. Seven pieces have recently been recovered, but only one makes it into Davis’ updated score. Carmine Coppola had initially benefited from advice and assistance from both Davis and Brownlow. However, protecting the 1981 version with his father’s score has led Francis Ford Coppola and Zoetrope Studies to take legal action to prevent any Davis-scored version from being performed or marketed in the United States. Brownlow, Napoleon, 240-42.