Thomas Cragin

Muhlenberg College

One of the most powerful misconceptions I have encountered in teaching is the Dickensian vision of the guillotine and students’ association of the Revolution and France in general with “the lugubrious machine.” A more serious problem is of my own making. I tend to assign at least a few novels such as Flaubert’s Madame Bovary or Zola’s Germinal, which are contemptuous of the bourgeoisie from a bourgeois perspective. Lacenaire (1990) and The Widow of Saint-Pierre (2000) do precisely the same. Taken together or separately, the films provide an opportunity to address students’ morbid fascination with the guillotine and the association of France with capital punishment (especially ironic given France outlawed it in 1981 while the United States has not).

The two films illustrate the danger of costume dramas: the central characters become projections of our modern selves trapped in what are presented as the irrational and destructive prejudices and practices of the past. Thus the nineteenth century is made remote and comprehensible only in so far as we [may] reject it. Both Lacenaire and The Widow of Saint Pierre present criminals as sympathetic and both as beheaded by the system they defied, so that the past is portrayed not only as alien, but also as malevolent. The films comment on criminality, justice, and capital punishment. They begin and end with bloodshed, but for the most part addresses the character and motivations of the criminals and the elites who stood to profit by their crimes and executions.

Lacenaire

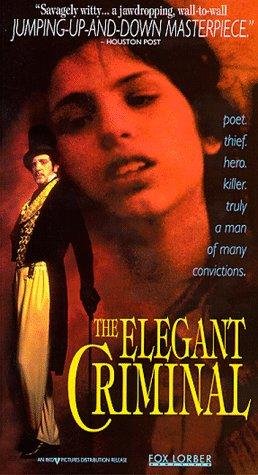

Lacenaire follows the life of one of the nineteenth century’s most infamous criminals, the dandy, self-proclaimed poet, and successful memoirist Pierre-François Lacenaire. Lacenaire committed a series of murders for which he was guillotined in 1836, but it was less his crimes than his published memoir that gained him notoriety. At times sticking quite closely to that memoir, the film recounts his tragic story.

Lacenaire begins with his last moments. Daniel Auteuil (until then known mainly for comic roles) is shown bravely facing execution. The opening scenes introduce the film’s major question: Were his murders inspired by his desire to commit suicide by means of the guillotine? Lacenaire claimed as much at the time of his arrest and the argument was echoed by the prosecutor in his trial and by scholars and biographers since. The film makes this a central question and answers it by showing major incidents in his life in a series of flashbacks.

Lacenaire begins with his last moments. Daniel Auteuil (until then known mainly for comic roles) is shown bravely facing execution. The opening scenes introduce the film’s major question: Were his murders inspired by his desire to commit suicide by means of the guillotine? Lacenaire claimed as much at the time of his arrest and the argument was echoed by the prosecutor in his trial and by scholars and biographers since. The film makes this a central question and answers it by showing major incidents in his life in a series of flashbacks.

These flashbacks are one of several techniques that director Francis Girod employs to demonstrate the film’s accuracy and students could be challenged to identify and discuss these. Each flashback is triggered either by Lacenaire’s survivors’ version of his memoir or by his own recollections written while he was in prison. By connecting the film’s flashbacks to the memoir, the film implies they are lifted from the published text. Yet it shows Lacenaire’s survivors editing his memoir to remove aspects that might offend the censors or the public, suggesting to viewers that the film is more truthful than the original memoir. This assertion that we are somehow more capable of seeing the truth than those mired in the prejudices of the nineteenth century is introduced at the film’s start when a phrenologist and his assistant interview Lacenaire and make a plaster cast of his head. This is faithful to the original memoir in which Lacenaire announced: “I foresee a whole shower of phrenologists, cranium-feelers, physiologists, anatomists . . . birds of prey that live on cadavers.”[1] The film’s phrenologist is presented as a charlatan: telling Lacenaire that he lacks the skull formations that would indicate a “born killer,” and a few minutes later, after Lacenaire’s execution, confidently lecturing his colleagues on Lacenaire’s inherent criminal traits.The implication is that we are better able to gauge what motivated Lacenaire than were his contemporaries.

An historian might challenge students to evaluate and compare criminological explanations then and now. While this film locates Lacenaire’s criminality in his social development, his own memoir readily displays contemporaries’ more common belief in fate. The real Lacenaire would have not put up with the pitiable reel Lacenaire. The former endeavoured to use his memoir to make himself into a proud master criminal, very much in keeping with those found in Balzac and Sue. And this also highlights a crucial element absent from the film: Lacenaire’s own memoir’s validation of his era’s belief in a criminal class with its own masters, journeymen, and apprentices, a dark underworld community. Of course, such a story would undercut the film’s elevation of the individual. Brief readings on criminology, popular belief, and French crime literature will certainly deepen students’ discussion.[2]

Before it examines the killer’s motives, the film introduces a subplot that will elevate him morally while demeaning those who convicted him and edited his memoir. It would be useful to ask students in what ways Hermine, a young woman whom Lacenaire treats as a surrogate daughter, inspires such impressions. After his death, Hermine is taken away by the chef de la Sûreté, Pierre Allard (Jean Poiret), who uses her body and mind for his own gratification. Allard’s rival, journalist Jacques Arago (Jacques Weber), lures Hermine away only to turn her into his own mistress. Their exploitation of Hermine is contrasted to the tenderness Lacenaire shows toward her in several flashbacks. This makes Lacenaire seem the more moral figure in the story compared to those entrusted with his memory who betray him. Once Girod has created the profound moral ambiguity for which he is famous, Lacenaire begins its examination of the criminal’s past that will turn him into a tragic figure, reminiscent of Victor Hugo’s 1829 Le dernier jour d’un condamné.

Before it examines the killer’s motives, the film introduces a subplot that will elevate him morally while demeaning those who convicted him and edited his memoir. It would be useful to ask students in what ways Hermine, a young woman whom Lacenaire treats as a surrogate daughter, inspires such impressions. After his death, Hermine is taken away by the chef de la Sûreté, Pierre Allard (Jean Poiret), who uses her body and mind for his own gratification. Allard’s rival, journalist Jacques Arago (Jacques Weber), lures Hermine away only to turn her into his own mistress. Their exploitation of Hermine is contrasted to the tenderness Lacenaire shows toward her in several flashbacks. This makes Lacenaire seem the more moral figure in the story compared to those entrusted with his memory who betray him. Once Girod has created the profound moral ambiguity for which he is famous, Lacenaire begins its examination of the criminal’s past that will turn him into a tragic figure, reminiscent of Victor Hugo’s 1829 Le dernier jour d’un condamné.

Students can usefully consider the forces against which Lacenaire struggled from childhood to the end of his life, what these reveal about his character and motivations, and what they suggest about the problems of the nineteenth-century bourgeoisie. Lacenaire is at war with the hypocrisy of the bourgeoisie of his childhood. The film depicts the repression, iron discipline, and hypocrisy of his Catholic education. He is betrayed by a friend for defending Protestant ideas; then transferred to a Jesuit school where he beats up an abusive pederast priest. Explaining later that “the seminary has made me what I am,” he begins to steal from his parents. This first crime is given further justification in the absence of his father and the cold indifference of his mother. The film’s mother, who reciprocates his younger brother’s almost illicit affections while shunning her eldest son, bears little resemblance to the mother described in Lacenaire’s published memoir, “devout without bigotism, . . . deeply virtuous without prudery, . . . sensitive to the troubles of others, . . . indulgent towards their faults and . . . resigned to her own sufferings [sic].”[3] Later in the film, we discover that this denial of maternal affection has left him scarred, unable to engage in a sexual relationship with “a woman of quality.” No mention is made in the film of his incestuous relationship with his sister, probably because this would undercut the film’s portrayal of a tragic hero. After his school expulsion, his father, a character driven by two impulses, enters the story. First, he is governed by bourgeois personal constraint (faithful to the memoir), made evident in his scolding Lacenaire for his “lechery.” Second, exposing the hypocrisy of the first, the father is obsessed by the guillotine; it dictates his politics (he favours the Terror and Napoleon over Louis XVIII because the former executed more people) and invokes his admiration, evident when he forces his son to gaze upon a guillotine and admire its beauty and simplicity (a misreading of the memoir, which instead suggests that his father pointed to the guillotine as a warning that misdeeds would lead young Lacenaire to a terrible end). As the flashback ends, the imprisoned Lacenaire tells a visitor the significance of that moment, which engendered his fascination for the fatal device. Once we’re shown the father’s hypocrisy and callousness, we accept how Lacenaire deceives him to pay off gambling debts. The army completes Lacenaire’s disillusionment by demonstrating that “No man is lazier than an officer.” It is only once his father dies a bankrupt that Lacenaire pursues a life of crime. Thus, the film’s flashbacks construct a Stendhalian victim driven to crime by his Catholic education, parental indifference, and army corruption.

Students should consider how the film strives to limit our disapproval of Lacenaire’s criminal activities. He turns to petty thievery only after being fired from his job as an editor. As petty thievery yields to organized robbery, Lacenaire seeks an accomplice. Implicitly incapable of killing, he needs a homicidal sidekick and, after a comedy of errors, he finds him in Avril. We see far more of their evolving tender homosexual relationship than we do of the double homicide that prompted their arrest and execution. We do not see the old woman Lacenaire murdered, and the crimes are filmed in a dark interior that denies the viewer much detail. In short, Lacenaire’s criminality, so central to his published memoir, has been marginalized. The man who repeatedly and proudly asserted his thirst for revenge, his hatred and contempt for mankind has vanished. The real Lacenaire proclaimed his own indomitable urge to destroy. [4]

Students could read the transcript of the trial in Stead’s translation and compare it to the film version which turns him into a champion of justice. When questioned by the police, he boldly confesses that he seduces and dominates through his gift with language, and enters the courtroom like an actor stepping on stage, accompanied by applause, which was highly unlikely in the actual event. Using flattery and wit, he is shown extending his control over the proceedings, humiliating the prosecutor to the delight of the audience, and persuading the presiding judge to let him speak freely. Lacenaire demands to be guillotined for his crimes and then denounces the failings of Restoration France. These scenes bear little or no resemblance to the actual trial which, as in any Assize Court, was dominated by the prosecutor and presiding judge.

If the popular press is any indication, most people in nineteenth- century France viewed crime as the product of evil. Each evil action led to another, poisoning the soul of the criminal, leading to greater felonies, as Lacenaire’s trajectory demonstrated. Historians treat Lacenaire’s memoirs either as the struggle of a young poet to achieve notoriety through a life of crime, with the perpetrator constructing a romantic identity for himself, or else as a catalogue of his society’s ills, his alienation, and descent into criminality. For nineteenth-century readers his memoirs were the fascinating confessions of a man consumed with evil, arriving step by step to murder.

The Widow of Saint-Pierre

The Widow of Saint-Pierre (2000) shares enough similarities with Lacenaire to work well together. Four years before making Widow, director Patrice Leconte’s lavish costume drama, Ridicule, won Césars for Best Director and Best film. What made Ridicule such a critical success was not some slavish attempt to recreate life at Versailles, but its more profound presentation of “man’s struggle against the forces that contain him.”[5] Widow depicts this as well as does Girod’s Lacenaire. The films deal with similar themes and have a similar structure. Like Lacenaire, Widow opens with the dénouement: Madame La Pauline (Juliette Binoche) observes a scene we can only hear: drumbeats of the execution that will leave her a widow. As in Lacenaire, the film then goes back in time and, like Lacenaire, stakes its claims to historical accuracy. Captions explain that the script is based on original judicial records, yet, again like Lacenaire, the film moves beyond these records to unveil a greater truth. For our purposes, what is more, Widow conveys this through the same cinematic conventions: the audience is made to identify with the three central characters and condemn the forces that destroy them. Set in Saint-Pierre and Miquelon and filmed in nearby Louisbourg in Nova Scotia, Widow tells the tragic tale of Captain Jean La Pauline (Daniel Auteuil again!), whose wife embodies Jules Michelet’s appraisal of officers’ wives: “Nothing is sadder to see than these poor women sharing all the hardships of military life because of their affection and sense of duty.”[6] Madame la Pauline takes pity on a convicted murderer and reforms and rehabilitates him in the eyes of the island’s fishermen. But all her good work is foiled by Saint-Pierre’s bourgeoisie. Even more directly than Lacenaire, Widow presents a self-satisfied, hypocritical bourgeoisie using the guillotine to display their authority against guilty parties whose inner worth we have observed.

Widow differs from Lacenaire in that it is mainstream cinema at its best and worst. Patrice Leconte consciously crafts films that will have mass appeal. As a result, Widow shows students the mechanisms directors use to elicit audience responses. I would begin my discussion of this film by asking students about the lighting of the first scenes. After the dimly lit opening showing Madame La Pauline’s tragic vigil, the film cuts to two different vignettes: a senseless crime and an idyllic setting. In the first we learn we are in Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon in1849, and see, in near-total darkness, two fishermen – Louis Ollivier and Ariel Neel Auguste (Emir Kusturica) – row through the fog to settle their absurd debate about whether Captain Coupard is “gros” or “gras.” In the very next scene we see Captain Jean La Pauline overseeing the unloading of his prize horse from a ship set against a picturesque sea of azure and an almost white sky. What do these visual differences convey? How are we meant to respond to the exchanges between Ollivier and Auguste on the one hand and between the Captain and his wife on the other?

Widow differs from Lacenaire in that it is mainstream cinema at its best and worst. Patrice Leconte consciously crafts films that will have mass appeal. As a result, Widow shows students the mechanisms directors use to elicit audience responses. I would begin my discussion of this film by asking students about the lighting of the first scenes. After the dimly lit opening showing Madame La Pauline’s tragic vigil, the film cuts to two different vignettes: a senseless crime and an idyllic setting. In the first we learn we are in Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon in1849, and see, in near-total darkness, two fishermen – Louis Ollivier and Ariel Neel Auguste (Emir Kusturica) – row through the fog to settle their absurd debate about whether Captain Coupard is “gros” or “gras.” In the very next scene we see Captain Jean La Pauline overseeing the unloading of his prize horse from a ship set against a picturesque sea of azure and an almost white sky. What do these visual differences convey? How are we meant to respond to the exchanges between Ollivier and Auguste on the one hand and between the Captain and his wife on the other?

Like Lacenaire, Widow constructs an initial identification with the protagonist(s) and then proceeds to establish the film’s historical credentials. Hence, within Ollivier and Auguste’s trial for murder, we are shown flashbacks of Auguste ruthlessly striking Coupard.

These events did take place, but in 1888 not in 1849 as in the film, a significant distortion that permits developments in Saint Pierre to parallel events in France during the Second Republic. Thus a clear distinction is drawn early on between the island’s elites (in the courtroom) and the lower classes, the fishermen (on the sea) and their families (in the town). Ollivier is sentenced to transportation, Auguste to death. As the two are carted to the local army prison, the townspeople preempt official justice by pelting the two men with rocks, killing Ollivier. Students can discuss what these scenes suggest about officialdom and the power of community (which kills the less guilty man and spares the murderer). The working- class community on the island offers a theme worthy of further exploration.

A convention of mainstream cinema is to have the plot revolve around a series of tensions, in this case between officialdom and the people, between the bourgeoisie and Captain La Pauline, between the Captain and his wife, all of which stem from Madame La Pauline’s efforts to reform Auguste. Her motives are ambiguous. Should we see in her the virtuous long-suffering do-gooder Binoche of The English Patient or bursting with sexual desire and challenging social conventions asin The Children of the Century (a role she often plays)? Widow maintains this tension by allowing both readings. Madame La Pauline takes Auguste around the island, to help (and it turns out also to bed) the women of the community. Meanwhile, the decisions of the ever-caustic governor of the island and his coterie of bourgeois advisors are upheld by the French Republic, and a guillotine is on its way. Auguste has become so pliable and helpful that by the second half of the film he seems thoroughly rehabilitated, even risking his life to rescue a damsel in distress, and also learning to read. When the guillotine finally arrives, an immigrant desperate for money is dragooned to become executioner, but the townspeople threaten violence to protect their now-beloved Auguste. The filmmakers labor to connect these developments to what was happening in Paris. In contrast to the June Days, Captain La Pauline, inspired by his wife, brings the island’s few troops to the side of the people. But the evil bourgeoisie carry the day on the island as they did under Louis Napoleon. A ship arrives from France bringing the captain’s replacement, thus decapitating the people’s resistance. As troops re-establish bourgeois control, the captain calmly submits to his recall to France, where, the island’s elites rejoice, his fate has already been sealed. The film ends where it began with the Captain’s death before a firing squad and Auguste’s simultaneous beheading, leaving Madame La Pauline doubly widowed by “the widow” (one of the guillotine’s nicknames). Students can discuss how the film weaves in an unconscious acceptance of the story’s message even while telling its suspenseful tale.

Widow elicits questioning of its assertions about the Revolution of 1848, the rise of the Second Empire, and the role of the bourgeoisie. The fishermen’s rebellion has been instigated by Madame La Pauline and facilitated by the good Captain’s support, implying that France needed reform-minded, educated bourgeois leaders to defy its conventions without threatening its hegemony. It would be valuable for students to compare the presentation of Saint-Pierre with what they might know about the actual leadership, motivations, and nature of popular protest in France in that period.

* * *

Each film condemns the bourgeoisie, presented as loathsome. Lacenaire’s parents are callous and send their children to be educated by sadistic pedophiles; his associates betray his memory and sexually exploit his daughter. In Widow, the bourgeois elite depicts Captain La Pauline as a cuckold and his wife, whom they dub “Madame La” because she is unworthy of a full name, as a fallen woman. They insist on Auguste’s execution despite his rehabilitation not out of concern over his crime, but merely to defend their own authority. In both films, the guillotine signifies bourgeois hegemony and both films play on our own sensibility which recoils at capital punishment, while fetishizing the killing machine.

But what lies beneath this surface makes for better discussion. Neither film presents a hero from the lower classes. Lacenaire was a bourgeois, and the film insists on this. He can outwit the bourgeoisie with his powers of persuasion. The film further suggests (in a complete fabrication) that he could dominate one of the most dehumanizing and controlling of all nineteenth-century French spaces, the Assize court. In Widow, the refined, romantic, and powerful Captain and his compassionate wife, who reforms a murderer and urges the populace that had initially tried to kill him to defend his life at great risk to their own, are also bourgeois. Thus, both films celebrate the resistance of educated and sensitive middle-class characters who demonstrate the most profound form of individualism. They violate customs, mores, and laws and are, therefore, thrust outside the community of bourgeois respectability (and into our own). This depiction is Lacenaire’s posthumous victory since, as Laurence Senelick explains, he struggled through his memoir “to avoid being lost in the faceless mob, to validate his individuality, . . . and to become a murderer whose acts, however base and ignoble, verified his distinction from the rest of mankind.”[7] Stamos Metzidakis notes that the “quiet submission to forces which neither the Captain nor Neel [Auguste] completely respects constitutes an essentially Romantic gesture of defiance and self-sacrifice” which demonstrates “extraordinary dignity, honesty, and strength.”[8] Perhaps, but these characters’ “quiet submission” without struggle, fear, or sorrow hammers home an idealized image of the isolated individual. It certainly provides an opportunity to discuss nineteenth-century responses or their absence before a variety of injustices and abuses.

Equally disturbing is the two films’ eroticization of capital punishment, especially in the Widow. Girod transforms Lacenaire’s very real infamy into modern celebrity culture, with noble and middle class women visiting his cell like fans backstage at a rock concert. Widow goes beyond this to imply that Madame La is turned on by the thought of capital punishment though she channels this desire safely toward her husband. Whatever celebrity murderers mustered in the nineteenth–century, it hardly had women tearing off their clothes. Indeed what makes Widow so disturbing is its suggestion that Madame La is motivated by passion more than compassion. Her sexual desire is mirrored by her husband’s choice of martyrdom: their sacrifices are self-gratifying. Madame’s punishment is the most profoundly bourgeois of all since her pursuit of reform and justice (her hands trembling with desire as she touches Auguste) fails to save Auguste and directly causes her husband’s death and, so, her own downfall. For all its pretences, Widow’s destruction of the La Paulines is nearly as nineteenth-century as Flaubert’s destruction of Madame Bovary.

The two films would make a marvellous pair for the end of a course on modern France since they would allow students to discuss both the obvious imitation of late–nineteenth-century critiques of bourgeois corruption and the less obvious idealization of bourgeois individualism. Both films offer a fascinating demonstration of the survival of bourgeois ideals in the twenty-first century. But, one might ask, what has become of nineteenth-century collective resistance?

Francis Girod, Director, Lacenaire [The Elegant Criminal] (1990) Color, 125 min., France, Partner’s Productions, Union Générale Cinématographique (UGC), Hachette Première.

Patrice Leconte, Director, La veuve de Saint-Pierre [The Widow of Saint-Pierre], (2000), Color, 112 min., France, Canada, Cinémaginaire Inc, Epithète Films, France 2 Cinéma.

- Pierre-François Lacenaire, The Memoirs of Lacenaire, ed. and trans. by Philip John Stead, (London, Staples Press, 1952), p.55.

- On criminological theories in brief, see Gordon Wright, Between the Guillotine and Liberty: Two Centuries of the Crime Problem in France, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 109-117. For a brief discussion of popular beliefs about criminality, see Thomas Cragin, Murder in Parisian Streets: Manufacturing Crime and Justice in the Popular Press, 1830-1900, (Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 2006), pp.145-168. On the connection between Lacenaire’s memoir and the literature that inspired his creation of a mythic self, see the insightful analysis of Laurence Senelick, The Prestige of Evil: The Murderer as Romantic Hero from Sade to Lacenaire, (New York: Garland, 1987), 277-293. The film’s beginning and end portray what most fascinated Lacenaire’s contemporaries: the last moments of the condemned, the spectacle of execution before a large crowd barely controlled by the civil authority, the condemned’s approach to the scaffold, his courage, and his annihilation.

- Lacenaire, Memoirs, p.65.

- Lacenaire, Memoirs, pp.59, 147.

- Rémi Fournier Lanzoni, French Cinema: From Its Beginnings to the Present, (New York: Continuum, 2005), p.395.

- Jules Michelet, The People, trans. by John P. McKay, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1973), p.76.

- Senelick, Prestige of Evil, p.279.

- Stamos Metzidakis, “Capital Punishment and Sexual Politics in Lecomte’s La Veuve de Saint Pierre,” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies, 9:4 (December 2005): 353-368, 360.