Michael Sibalis

Wilfrid Laurier University

When in 1942 Sacha Guitry wrote and directed a movie about the woman he described as “a little-known but very illustrious personage,” he titled it Le Destin Fabuleux de Désirée Clary.[1] “Fabulous” is indeed an apt word for the life story of Bernardine Eugénie Désirée Clary (1771-1860). Her father, François Clary (1725-1794), was a wealthy and influential Marseillais shipowner involved in international trade (and not in fact a silk-merchant, although most accounts of Désirée’s life – both historical and fictional – say so, even portraying her as selling silks in his shop as a girl).[2] Désirée was the youngest of his thirteen children (by two wives), ten of whom lived into adulthood. Her sister Julie married Joseph Bonaparte in August 1794 and Désirée became engaged to his younger brother, Napoleon, who preferred to call her Eugénie. We have few reliable details about their relationship, but it did inspire Napoleon to pen a romantic novella, Clisson and Eugénie (unpublished in his day).[3] In early 1796, however, Napoleon ditched Désirée for Josephine de Beauharnais and in 1798 she married General Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte. Napoleon made Bernadotte Marshal of France in 1804 and in 1810 the Swedish Diet elected him Crown Prince and future successor to their childless king. As David Bell has put it, “the era’s tornado of possibilities landed [Désirée], improbably, in Stockholm as queen of Sweden (her descendants sit on the Swedish throne to this day).”[4]

Désirée Clary would today be unknown to anyone but specialists in the history of the Napoleonic Era or the Swedish monarchy but for various fictional representations of her life. In particular, there is Annemarie Selinko’s best-selling novel Désirée, first published in German in 1951[5] and translated into most major languages. Two English-language translations appeared in 1953: one British and one American, both of which have been republished many times.[6] The wording of these two versions differ considerably. Each has sentences not included in the other, but the British seems more complete, while entire pages were cut in its American counterpart. Twentieth Century Fox bought the film rights and released Désirée as a “major motion picture” in November 1954.

Désirée Clary would today be unknown to anyone but specialists in the history of the Napoleonic Era or the Swedish monarchy but for various fictional representations of her life. In particular, there is Annemarie Selinko’s best-selling novel Désirée, first published in German in 1951[5] and translated into most major languages. Two English-language translations appeared in 1953: one British and one American, both of which have been republished many times.[6] The wording of these two versions differ considerably. Each has sentences not included in the other, but the British seems more complete, while entire pages were cut in its American counterpart. Twentieth Century Fox bought the film rights and released Désirée as a “major motion picture” in November 1954.

An American fan named Julie Zetterberg Sardo maintains a website dedicated to the novel and the movie. She writes that she first read the book in junior high school and “[i]t helped spark an interest in history that led to my decision to seek and receive a B.A. in history from the University of Washington.” Hers was not an uncommon reaction and there are many comments like this one in the website’s guestbook: “I first read Désirée when I was 15 years old. It was assigned by my history teacher as she felt novels gave students a painless way to learn history. I completely adored the book and read it at least six or seven time. Since then I have been fascinated by Désirée and the history of the Napoleonic era.”[7] Most (but not all) such entries are by women who encountered Désirée’s story in their teens. And here is my own embarrassing confession. I saw the movie on television in the summer of 1964 and a few months later bought a second-hand copy of the novel

for fifty cents (it’s still on my bookshelf); this piqued my interest in Napoleon and his times, eventually leading me to my career as a French historian. Now, fifty years later, watching the movie once again on DVD and rereading the novel (in both English-language translations) has provided me an opportunity to move beyond an adolescent infatuation with the story they tell and to assess their value for teaching history.

for fifty cents (it’s still on my bookshelf); this piqued my interest in Napoleon and his times, eventually leading me to my career as a French historian. Now, fifty years later, watching the movie once again on DVD and rereading the novel (in both English-language translations) has provided me an opportunity to move beyond an adolescent infatuation with the story they tell and to assess their value for teaching history.

The novel takes the form of Désirée Clary’s private journal from the day before she meets Joseph Bonaparte in late March 1794 to her coronation as Queen Desideria of Sweden (21 August 1829). The reader sees thirty-five years of momentous events and dozens of historical personalities (as well as more than a few fictional ones) entirely through Désirée’s eyes. Of course, Désirée’s relationships with Napoleon and Bernadotte are the core of the story. “How strange, madame,” Sweden’s Princess Sofia Albertina remarks to her, “that the two outstanding men of our times have been in love with you. You’re really no beauty” (p. 579).[8] Indeed, the fictional Désirée is not a conventional heroine. She is, by her own admission, rather plain, badly educated, politically obtuse – “I don’t know anything about politics” (p. 120) – and reluctant to take the lessons urged on her by Bernadotte. Even worse for a crown princess and queen, she remains at a heart a bourgeoise who hates palaces and bristles at court etiquette. On the other hand, she is also spirited, generous, perceptive, a good judge of character and deeply in love with Bernadotte. She is moreover firmly committed to the ideals of the French Revolution and appalled by the human cost of the Napoleonic Wars.

There is some truth to this fiction. Queen Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotte of Sweden described the historical Désirée this way: “The Princess is small, not pretty and with no figure whatsoever. Her timidity makes her brusque. […] A spoilt child, but sweet, kind and compassionate.”[9] She lacked the social graces and Bernadotte urged her “to cultivate social accomplishments,” but, as one of his biographers notes, might “as well ask a dove to arch its neck like a swan.”[10] As for love, it is not clear from the record whether or not Napoleon ever really loved her, although some evidence suggests a lingering affection. On St. Helena, when Napoleon claimed that “it was because he had taken her maidenhead that he created Bernadotte a marshal, prince and king,”[11] he was embittered and quite likely lying. Désirée was heart-broken when Napoleon broke off their engagement (her letters testify to this), but she quickly got over her despair. She and Bernadotte may have fallen in love, although her main reason for marrying him was, in her own words, that “he was man enough to withstand [i.e. stand up to] Napoleon.”[12] She and Bernadotte were separated for long periods when he was on campaign, and between 1811 and 1823 she lived in Paris, he in Sweden. She did what she could to advance his career, but her primary interest was always her family and not politics.[13]

There is some truth to this fiction. Queen Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotte of Sweden described the historical Désirée this way: “The Princess is small, not pretty and with no figure whatsoever. Her timidity makes her brusque. […] A spoilt child, but sweet, kind and compassionate.”[9] She lacked the social graces and Bernadotte urged her “to cultivate social accomplishments,” but, as one of his biographers notes, might “as well ask a dove to arch its neck like a swan.”[10] As for love, it is not clear from the record whether or not Napoleon ever really loved her, although some evidence suggests a lingering affection. On St. Helena, when Napoleon claimed that “it was because he had taken her maidenhead that he created Bernadotte a marshal, prince and king,”[11] he was embittered and quite likely lying. Désirée was heart-broken when Napoleon broke off their engagement (her letters testify to this), but she quickly got over her despair. She and Bernadotte may have fallen in love, although her main reason for marrying him was, in her own words, that “he was man enough to withstand [i.e. stand up to] Napoleon.”[12] She and Bernadotte were separated for long periods when he was on campaign, and between 1811 and 1823 she lived in Paris, he in Sweden. She did what she could to advance his career, but her primary interest was always her family and not politics.[13]

Selinko notes on its very last page that her novel “is based on history” but “has its own reality.” There are certainly anachronisms and errors, both factual and chronological, that betray Selinko’s lack of understanding of the period. For instance (to take only three examples), she describes the Vendémiaire uprising as a “hunger riot” (pp. 93, 404) that takes place several months after, rather than just before, the election of the five Directors; her account of the Brumaire coup d’état is hopelessly confused; and she has the Marseillaise (banned under the Empire) playing throughout the period, including at Napoleon’s coronation. Other “mistakes” were conscious, however. Selinko pruned the Clary family down to three siblings and freely invented dramatic incidents that never took place: “In the light of my own interpretation of the characters and of their reactions I, for one, have chosen to believe that what might have happened did happen” (p. 594). Most notably, Selinko’s Désirée makes a secret trip to Paris and enters Madame Tallien’s salon just in time to hear the announcement of Napoleon’s engagement to Josephine (she hurls a glass of champagne at the couple); goes to the Tuileries late one night in 1804 to beg for the life of the duc d’Enghien (Napoleon brushes her off but reveals his plans to become Emperor); receives a surprise visit in December 1812 from Napoleon who has just returned from the Russian Campaign (he wants her to write Bernadotte, who has been advising the Czar); and most dramatically persuades Napoleon to give himself up to the Allies after Waterloo in 1815 in order to spare France more destruction and civil war (he personally surrenders to her as Crown Princess of Sweden, handing her “the sword of Waterloo”). Imaginary (and highly improbable) scenes like these place fictional Désirée – and the reader – at the very centre of events.

What makes the novel interesting, however, is not the unfolding of history; it is the rift between Napoleon (representing political tyranny) on the one side and Désirée and Bernadotte (standing for patriotism and republicanism) on the other. Selinko (1914-1986) was an Austrian journalist married to a Danish diplomat. She was active in the Danish Resistance to Hitler, escaped to Sweden in 1943 and worked there as an interpreter for Count Folke Bernadotte when he brought thirty-thousand refugees from German concentration camps to Sweden in April 1945.These experiences inflect Selinko’s narrative. Her Désirée Clary and Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte are worthy ancestors of the humanitarian Folke Bernadotte. As for Napoleon:

“While Selinko avoids the crudely obviously comparison of Napoleon to Hitler, the corroding effects of unlimited power and the triumph of human freedom – exemplified by the Declaration of the Rights of Man [1789] – are themes that resonate throughout her narrative. [… R]eaders experience through Désirée’s diary Napoleon’s gradual corruption by ambition and essentially limitless power. Faced with similar lures of domination and prestige, Bernadotte resists temptation.”[14]

Désirée remains, throughout the course of the novel, an admirer of the principles of the French Revolution as embodied by the Marseillaise – “song of my childhood” (243), “anthem of a free people” (p. 259) – and the Declaration of the Rights of Man. That Désirée’s (fictional) journal mentions several times that the Revolution freed Europe’s Jews had obvious significance in the aftermath of World War II. A prescient Désirée even has entirely anachronistic hopes for Sweden’s future. Bernadotte and the Swedish aristocracy want to restore the country’s military might, but Désirée has a different dream: “Sweden is a small country […] with only a few million inhabitants, isn’t it? Only through humanitarianisms can Sweden become great, Jean-Baptiste” (p. 368). “[Y]our little country will then really be a great power, Count [Rosen]. But different from what you are imagining. A great power whose kings will make no more wars, but have time to write poetry, to compose music” (p. 422) – a portrait, in other words, of her future grandson, Oscar II (reigned 1872-1907).

The novel portrays Napoleon as a domineering tyrant who has betrayed the French Revolution and bullies family, subordinates and allies. He is immensely self-confident from the start and foresees his future greatness, telling Désirée in 1794, “I am my destiny. […] I shall do great things. I was born to build states and to rule them. I am one of the men who make world history” (p. 40). Having fallen out of love with him, however, Désirée begins to see through Napoleon’s rhetoric and to compare him to her husband: “He cares nothing for the Republic, or for the rights of its citizens; nor could he understand a man like Jean-Baptiste” (p. 167). And in 1805, she reflects on Napoleon’s hypocritical justifications for war:

The novel portrays Napoleon as a domineering tyrant who has betrayed the French Revolution and bullies family, subordinates and allies. He is immensely self-confident from the start and foresees his future greatness, telling Désirée in 1794, “I am my destiny. […] I shall do great things. I was born to build states and to rule them. I am one of the men who make world history” (p. 40). Having fallen out of love with him, however, Désirée begins to see through Napoleon’s rhetoric and to compare him to her husband: “He cares nothing for the Republic, or for the rights of its citizens; nor could he understand a man like Jean-Baptiste” (p. 167). And in 1805, she reflects on Napoleon’s hypocritical justifications for war:

“Why does Napoleon make them march, these young men, into still more new wars, still more new victories? The frontiers of France have not needed to be defended for a long time. […] Or is he no longer concerned about France but only himself, Napoleon, the Emperor –? […] Instead, he applied [the Rights of Man] to his own devices, paying lip-service to freedom while he enslaved the nation – condoning bloodshed in the name of the Rights of Man” (p. 255).

Bernadotte is the anti-Napoleon and the novel’s real hero. He proves himself (successively) a brilliant general, a hardworking minister of war, and a progressive administrator of conquered Hanover and the Hanseatic towns. He makes war not for glory and Empire, but for the Rights of Man, to defend France and her Revolution, and eventually to overthrow Napoleonic tyranny. A self-confessed “confirmed Republican” – “I have sworn loyalty to the Republic and under all circumstances will uphold our Constitution” – he refuses to stage a coup d’état and make himself dictator in 1799 (pp. 157, 166). He eventually accepts becoming crown prince (and later king) of Sweden only because the offer comes from the Swedish people. He then helps forge the alliance that will defeat Napoleon and liberate Europe. The fictional Bernadotte, still faithful to his republican ideals, rejects the Czar’s suggestion that he replace Napoleon on the French throne; the historical Bernadotte, of course, intrigued unsuccessfully for the crown of France.

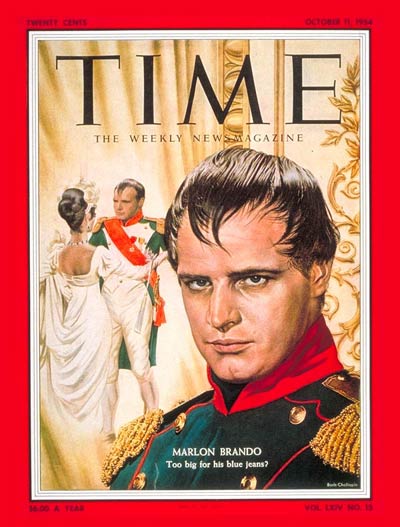

The transfer to the screen minimizes the novel’s ideological conflicts to focus on the love story. Only the most dramatic events remain and the movie closes with Napoleon’s surrender to Désirée in 1815 rather than her coronation in 1829, which ends the novel. Napoleon never ceases to love Désirée, who, she tells him in 1815, did fall out of love with him “somewhere along the way.” She is besotted with her high-minded husband and Bernadotte loves her deeply, but is suspicious of Napoleon’s attentions to her. Jean Simmons is charmingly believable (albeit too beautiful) as Désirée, evolving with ease from a high-spirited 15-year-old to an elegant crown princess. Merle Oberon is a dazzling Josephine and Michael Rennie a stalwart Bernadotte, but Marlon Brando’s Napoleon dominates the screen. This was hardly a typical role for the young Brando and a surprising casting decision, yet it works. Although the New York Times gave the movie a negative review (18 November 1954), cackling that it was “a streetcar named ‘Désirée’,” Time Magazine put Brando in Napoleonic costume on its cover with the enigmatic caption: “Too Big for His Breeches?” (11 October 1954).

Désirée was filmed in Cinescope, but rarely uses the wide screen to advantage. The costumes are magnificent and the indoor sets beautiful. There are splendid recreations of Napoleon’s and Josephine’s coronation (Jacques-Louis David’s famous painting comes to life) and a court ball on New Year’s Eve 1811. But the rare outdoor scenes appear tawdry and artificial. The retreat from Moscow, for example, is depicted by drums, tattered tricolor flags and flames caught up in a snowstorm. It is the characters who carry the movie.

Désirée was filmed in Cinescope, but rarely uses the wide screen to advantage. The costumes are magnificent and the indoor sets beautiful. There are splendid recreations of Napoleon’s and Josephine’s coronation (Jacques-Louis David’s famous painting comes to life) and a court ball on New Year’s Eve 1811. But the rare outdoor scenes appear tawdry and artificial. The retreat from Moscow, for example, is depicted by drums, tattered tricolor flags and flames caught up in a snowstorm. It is the characters who carry the movie.

Napoleon is still the bully, but he justifies himself better in the movie than in the book. He tells Désirée’s brother Étienne in 1794: “It is our sacred duty to instill into all the European peoples our great idea of liberty, equality and fraternity and if necessary with the help of cannon.” And to Désirée in 1798: “Deeds await me of which the present generation cannot even dream. These chuckleheads who call me bloodthirsty, mad, ambitious – I am none of these. […] I am the French Revolution and I shall know how to protect it.” The final verdict – an ambivalent one – on his rule comes in his last exchange with Désirée in 1815:

Napoleon: I’ve had to shed blood, but only where it was indicated. […] I made war in order to secure peace, not for a year, but for a dozen centuries. I dreamed of a United States of Europe. Frenchmen, Italians, Germans, Poles, Russians and all the others. One law, one coinage, one people. Was that so rash a dream?

Désirée: No, only the way you dreamed it.

If Désirée’s attitude is less hostile in the movie than in the book, Bernadotte, on the other hand, directly confronts the Emperor: “I remember the ideals of my youth, Sire. There are times I feel they have been betrayed. […] You were born to command, Sire. I was not born to obey.”

If Désirée’s attitude is less hostile in the movie than in the book, Bernadotte, on the other hand, directly confronts the Emperor: “I remember the ideals of my youth, Sire. There are times I feel they have been betrayed. […] You were born to command, Sire. I was not born to obey.”

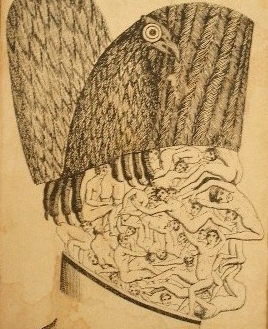

It has always been hard to be dispassionate about Napoleon. The Napoleonic legend was first fabricated by Napoleon and his supporters from the mid-1790s onward. Ever since his fall, countless poets, novelists and eventually movie directors (think of Abel Gance) – as well as certain historians – have promoted an image of him as the genius who saved France from chaos and spread revolutionary principles throughout Europe. At the other extreme is the “dark legend” or “counter-legend” of Napoleon as the insatiably ambitious tyrant, a figure (in H.G. Wells’s words) “of almost incredible self-conceit, of vanity, greed and cunning, of callous contempt and disregard of all who trusted him, and of a grandiose aping of Caesar, Alexander, and Charlemagne.”[15]

The novel Désirée may not go as far as Wells in its condemnation of Napoleon, but it shows him throughout to be willful, self-centred and authoritarian. He betrays the ideals of the French Revolution and bleeds France dry in pursuit of European domination. The movie has a somewhat more positive take on Napoleon. He is still cocksure, domineering and egotistical, but also dynamic and inspiring. He has a gentle side, too, particularly when interacting with Désirée. After all, the love story would make no sense  to moviegoers if Napoleon were a monster. Marlon Brando’s performance has something to do with it; viewers see the man beneath the autocrat. In the end, we cannot help but feel a twinge of pity for the defeated Emperor as he surrenders his sword to Désirée and agrees to go into an exile from which there can be no return.

to moviegoers if Napoleon were a monster. Marlon Brando’s performance has something to do with it; viewers see the man beneath the autocrat. In the end, we cannot help but feel a twinge of pity for the defeated Emperor as he surrenders his sword to Désirée and agrees to go into an exile from which there can be no return.

Neither the book nor the movie would be of much use in a university classroom, except perhaps for a discussion of representations of Napoleon in popular culture. Their historical content is simply too slight and too inaccurate to give university students any genuine understanding of the period or its personalities. On the other hand, reading the novel or watching the movie might well stimulate an interest in the Napoleonic era among younger students in high school or junior high and encourage them to further investigation of Napoleon and his times. After all, in this respect, they have a proven track record.

Annemarie Selinko, Désirée, translated by Arnold Bender and E. W. Dickes (London : William Heinemann, 1953); Désirée (New York: William Morrow & Company, 1953).

Henry Coster, Director, Désirée, 1954, Color, 110 min, USA, Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation.

- Guitry’s movie is currently available on Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-P-2K5LAAP4

- The best biography is Gabriel Girod de l’Ain, Désirée Clary d’après sa correspondance inédite avec Bonaparte, Bernadotte et sa famille (Paris: Hachette, 1959). See also Dorothy Potter, “Marseilles to Stockholm – Bonaparte to Bernadotte: The unique life of Désirée Clary,” in W. Maierhofer, G.M. Roesch and C. Bland, eds., Women Against Napoleon (Frankfurt: Verlag, 2007), pp. 79-92. Catherine Bearne, A Queen of Napoleon’s Court: The Life-Story of Désirée Bernadotte (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1905) deals more with the Imperial Court than with Désirée herself. For Désirée’s own version of events as told to her court chamberlain in old age, see K.F.L. Hochschild, Désirée, Queen of Sweden and Norway, trans. M. Carey (NY: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1890), which is available online in the Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- Napoléon Bonaparte, Clisson et Eugénie (Paris: Fayard, 2007); Clisson and Eugénie (London: Gallic Books, 2009).

- David A. Bell, The First Total War (Boston, NY: Houghton Mifflin, 2007), p. 203.

- Annemarie Selinko, Désirée: Roman (Köln: Kiepenheuer und Witsch, 1951).

- Annemarie Selinko, Désirée, translated by Arnold Bender and E. W. Dickes (London : William Heinemann, 1953); Désirée (New York: William Morrow & Company, 1953). There is no translator indicated for the the American edition, but in a note on the reverse of the title page, the publishers “acknowledge the special assistance of Joy Gary in the preparation of the final American version of this novel.”

- http://www.nebula5.org/clary/desiree.html

- All quotations are from the more readily available American edition.

- Alan Palmer, Bernadotte: Napoleon’s Marshal, Sweden’s King (London: John Murray, 1990), p. 176.

- Sir Dunbar Plunket Barton, Bernadotte and Napoleon 1763-1810 (London: John Murray, 1921), p. 38.

- Napoleon at St. Helena: Memoirs of General Bertrand, Grand Marshal of the Palace, January to May 1821, ed. Paul Fleuriot de Langle (London: Cassell, 1953), p. 7. The original French is cruder. See Cahiers de Sainte-Hélène, Jamvier-Mai 1821 (Paris: Éditions Sulliver, 1949), p. 32: “c’est parce qu’il lui a pris le c[on] et le p[uit] de c[ul]” etc.

- Hochschild, Désirée, p. 41.

- Bearne, A Queen of Napoleon’s Court, p. 441; Palmer, Bernadotte, pp. 195-96.

- Potter, “Marseilles to Stockholm,” pp. 88-89.

- H.G. Wells, The Outline of History (Garden City, NY: Garden City Publishers, n.d.), p. 412.