Julia Clancy-Smith

University of Arizona

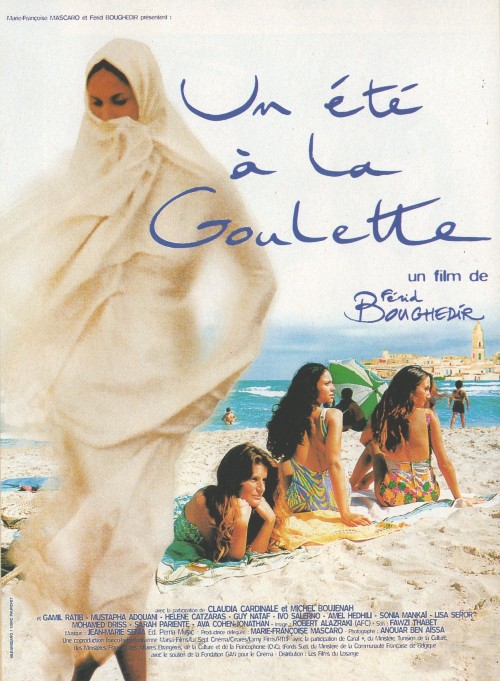

At first glance the two films Ce que le jour doit à la nuit and Un été à la Goulette (Arabic: Halq al-Wad) appear to be a somewhat curious match for teaching about colonialism through memoirs, monographs, and cinema. The second of these was produced by the internationally acclaimed Tunisian director and screenwriter Férid Boughedir (1944–) who was born in Hammam Lif, a Mediterranean suburb of Tunis.[1] Released two decades ago (in 1996), the film is set in the post-colonial period, during 1967, on the eve of the June “Six-Day” Arab-Israeli war–eleven years after Tunisia won its independence from France. It takes place in the port for Tunis, the town of La Goulette (a name of Italian origins) where even today Tunisians of diverse social backgrounds and tourists enjoy the beach with its stunning vista of the Gulf of Carthage, fish restaurants, and promenades.[2]

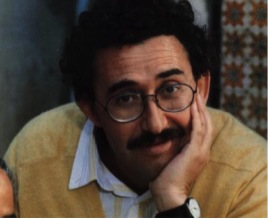

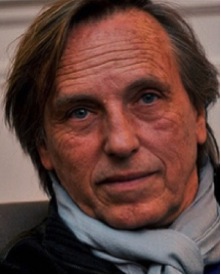

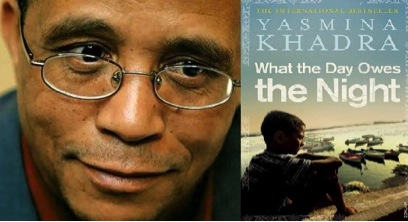

Ce que le jour doit à la nuit (released in 2012) is based upon a 2008 novel by Yasmina Khadra, one of the noms de plume of the Algerian writer Mohammed Moulessehoul (1955–) who has also published extensively under his real name.[3] If Moulessehoul’s life story is well worth an instructional digression, so is the biography of the film’s director, Alexandre Arcady (1947-) who was born in Algiers from the union of a Jewish mother and a father of Hungarian origins serving in the Foreign Legion; his family fled Algeria for France in 1961. In contrast to Summer in La Goulette, this film opens in western Algeria in the 1930s and follows the fortunes of a young Muslim lad, Younès (later renamed Jonas), originally of humble rural origins, through to the 1960s and beyond.

This review has relatively more to say about Boughedir’s Summer because I have used it for many years in the classroom and for a range of courses–undergraduate and graduate–devoted to topics such as Mediterranean migrations, colonialism/imperialism in comparative perspective, and women, gender, and empire.[4] So I have had more time to reflect on it and assess student responses and interpretations. I often combine La Goulette (and other films—of course, The Battle of Algiers, but also Noyés par balles) with semi-autobiographical works, such as Albert Memmi’s La statue de sel; Albert Camus’s Le premier homme, and Fadhma Amrouche’s Histoire de ma vie.[5] Needless to say, film showings are preceded by contextualization through hard-core history as well as geography. This semester is the first in which I paired Ce que le jour with Summer.

My major argument is that despite the apparent differences—time, place, the social class of the protagonists, etc.—these films complement each other, providing a much more nuanced view of French (or other imperial systems) colonialism and post-colonialism as lived, experienced, and imagined in twentieth-century North Africa and elsewhere.

Summer in La Goulette

Who doesn’t like to go to the beach? Boughedir artfully deploys all of the cultural stereotypes, clichés, and tropes about Mediterranean cultures. The film opens with shots of endless laundry lines like banners strung with clothes in the sun to dry, neighborhood women sip tea in cafés gossiping about their neighbors as their men while away the day by playing cards and drinking in all-male spaces, and, after long siestas, tribes of families gather at the shore armed with the inevitable pastèques (watermelons). The students are unfailingly amused and intrigued by what at first looks like a “fun film” — but soon divisive politics in places distant and nearby intervene. Here is a priceless opportunity to introduce the notion of Mediterranean peoples and their representation by other “Europeans” as somehow not only culturally but “racially” distinct, even inferior; this serves to complicate considerations of “Orientalism.” “They” are all noisy, emotional, tribal, and prone to insouciance; Mediterranean masculinities often assume the guise of harassment of girls and women passing in the streets. Directly related, several elements perplex or startle in a good sense student audiences: that the Tunisians or North Africans, Muslims and Jews, are included in the category Mediterranean; that the folks characterized in the literature as formerly “the colonizer” socialize daily with the “colonized” after the end of empire; that Sicilo-Italians still reside in a post-colonial state; and that language, the daily means of communication, reflects not only France’s influence but also that of the wider Mediterranean world.

Who doesn’t like to go to the beach? Boughedir artfully deploys all of the cultural stereotypes, clichés, and tropes about Mediterranean cultures. The film opens with shots of endless laundry lines like banners strung with clothes in the sun to dry, neighborhood women sip tea in cafés gossiping about their neighbors as their men while away the day by playing cards and drinking in all-male spaces, and, after long siestas, tribes of families gather at the shore armed with the inevitable pastèques (watermelons). The students are unfailingly amused and intrigued by what at first looks like a “fun film” — but soon divisive politics in places distant and nearby intervene. Here is a priceless opportunity to introduce the notion of Mediterranean peoples and their representation by other “Europeans” as somehow not only culturally but “racially” distinct, even inferior; this serves to complicate considerations of “Orientalism.” “They” are all noisy, emotional, tribal, and prone to insouciance; Mediterranean masculinities often assume the guise of harassment of girls and women passing in the streets. Directly related, several elements perplex or startle in a good sense student audiences: that the Tunisians or North Africans, Muslims and Jews, are included in the category Mediterranean; that the folks characterized in the literature as formerly “the colonizer” socialize daily with the “colonized” after the end of empire; that Sicilo-Italians still reside in a post-colonial state; and that language, the daily means of communication, reflects not only France’s influence but also that of the wider Mediterranean world.

Regarding that last point, the dialogue accurately reproduces the linguistic mixity of North Africa in this period and earlier. For example, the Sicilian seamstress begins a sentence in French, throws in a few Arabic terms (Tunisian dialectic or darja) and then completes her observations in Italian. This offers another teachable moment about polyglot port-cities, orality, and the fact that many of the “Europeans” had migrated to Tunisia before 1830 and the French conquest of Algeria. (Unfortunately, the English sub-titles can never do justice to the tri-lingual dialogue.)

Several family-based plots intertwine. Three young women, close friends from the same working class environment, but from different religions, make a vow in La Goulette’s cathedral before the statue of the Virgin of Trapani to lose their virginity before their sixteenth birthday. Another set of friendships involve the fathers of the three girls, Youssef, a Muslim and tram worker, and his best buddies Jojo, a Jew who sells a quintessential Tunisian delicacy (brik, a pastry fried in olive oil), and Giuseppe, a fisherman. The Italian actress, Claudia Cardinale, a native of La Goulette, appears as herself in a hilarious (and realistic) scene of a lavish wedding thrown by the Jewish family whose guests include most of the townsfolk, irrespective of religion. The bad guy is Hadj Beji, the proprietor of the apartments where the families reside, who has recently returned from a pilgrimage to Mecca affecting “Eastern” manners; despite his pretentions of piety, Hadj Beji, an older man, lusts after Youssef’s daughter. What also fascinates students is the fact of co-residence—that families of different faiths resided in the same buildings in very intimate spatial proximity, often sharing prized Tunisian culinary dishes with each other. The month of June 1967 in La Goulette appears nearly idyllic. Then the village idiot, who incessantly listens to Radio Cairo, announces that war has broken out in the Middle East.

Several family-based plots intertwine. Three young women, close friends from the same working class environment, but from different religions, make a vow in La Goulette’s cathedral before the statue of the Virgin of Trapani to lose their virginity before their sixteenth birthday. Another set of friendships involve the fathers of the three girls, Youssef, a Muslim and tram worker, and his best buddies Jojo, a Jew who sells a quintessential Tunisian delicacy (brik, a pastry fried in olive oil), and Giuseppe, a fisherman. The Italian actress, Claudia Cardinale, a native of La Goulette, appears as herself in a hilarious (and realistic) scene of a lavish wedding thrown by the Jewish family whose guests include most of the townsfolk, irrespective of religion. The bad guy is Hadj Beji, the proprietor of the apartments where the families reside, who has recently returned from a pilgrimage to Mecca affecting “Eastern” manners; despite his pretentions of piety, Hadj Beji, an older man, lusts after Youssef’s daughter. What also fascinates students is the fact of co-residence—that families of different faiths resided in the same buildings in very intimate spatial proximity, often sharing prized Tunisian culinary dishes with each other. The month of June 1967 in La Goulette appears nearly idyllic. Then the village idiot, who incessantly listens to Radio Cairo, announces that war has broken out in the Middle East.

Summer depicts the residue of a culturally striated landscape still found in some Mediterranean port cities even after empire’s demise. The annual festival to honor Santa Maria de Trapani, transplanted from Sicily before 1881, remained a collective celebration. As in the past, Muslims and Jews take part in this most cherished of public processions for Maltese and Sicilian Catholics. In Boughedir’s film, religion presents few barriers to residential cohabitation, socializing, or employment, although cross-religious sexual relations or marriages rarely occur, and if they do, social uproar ensues. Yet his film warns against the nostalgic notions of a sort of populist Mediterranean cosmopolitanism or convivencia free from intolerance, petty jealousies, daily struggles over resources, and moments of communal political contention. Indeed, we witness the “after-life” of anti-colonialism and nationalist passion as anti-Jewish sentiments tied to the Arab-Israeli conflict are expressed in the café by some inebriated male patrons. A heated argument ensues over the fact that some Tunisian Jews had from the start rejected the Zionist project and fully participated in the anti-colonial movement for independence from the inter-war period on.[6]

The instructor contemplating this film for class might consider it too local, too Tunisian or North African for the purposes of making larger, historical generalizations. However, once again, it portrays quite accurately the many histories of settler colonialism, dispelling monolithic categories or rigid binaries; Tunis-La Goulette can highlight comparisons with British-ruled Alexandria where similar social dynamics played out. In addition, Boughedir slyly but gently mocks the mental universe of La Goulette’s denizens who regard themselves as “le centre du monde,” which can be integrated into debates on the meanings of cosmopolitanism but is also a philosophical statement. It seems not only Americans suffer from delusions of exceptionalism; we all inhabit our own micro-social landscapes.

Moreover, the film unmasks the complexity of women and gender relations in a majority Muslim nation, as indexed by dress or clothing, a critical social marker. Some women still wear the traditional white safsari or cloak over their clothes when in public, others sport the latest fashion.[7] Finally for historians of French colonialism and “La plus grande France,” this film, with adequate historical framing, demonstrates that beneath the label “French” lurked other, older, and deeper cultural and political relationships—above all, the Italian-Tunisian connection.

Ce que le jour doit à la nuit

Ce que le jour is a more visually (and sensuously) stunning film as well as being more emotion-laden, at least according to my students. It opens in western Algeria with a struggling peasant family whose abundant wheat crop that year (in the 1930s) augurs well for paying off its debts to the caid (qa’id), who clearly entertains close ties with local colonial officials. When the caid arrives to press Issa (Younès’s father) to sell his land and crops to liquidate his financial liabilities, the father refuses. That night their fields are burned to the ground and the family loses everything; they migrate to  Oran to dwell in a miserable communal shantytown where Issa struggles as a day laborer whose wages are often “garnished” by French employers. But Issa has an older brother from whom he has long been estranged–Mohamed, a prosperous pharmacist in Oran who is married to a French (or pied-noir) woman, Madeleine; the couple is childless. After acrimonious encounters between the two brothers over Younès’s fate, the boy goes to live permanently with his uncle and aunt in a decidedly bourgeois household; significantly, his name is changed to Jonas and he is remade “white.”

Oran to dwell in a miserable communal shantytown where Issa struggles as a day laborer whose wages are often “garnished” by French employers. But Issa has an older brother from whom he has long been estranged–Mohamed, a prosperous pharmacist in Oran who is married to a French (or pied-noir) woman, Madeleine; the couple is childless. After acrimonious encounters between the two brothers over Younès’s fate, the boy goes to live permanently with his uncle and aunt in a decidedly bourgeois household; significantly, his name is changed to Jonas and he is remade “white.”

All seems more or less tranquil until, on the eve of the July 1940 British aerial bombardment of Mers-el-Kébir, the French police invade their household, accusing Mohamed of nationalist sympathies, and seize papers as well as a photograph of Messali Hadj, co-founder of the Étoile nord-africaine in Paris and the Parti du peuple algérien. The family leaves Oran for the safety of the Mediterranean town of Rio Salado (today known as al-Malah) whose inhabitants are mainly Spanish. Jonas makes friends with some European children and is enrolled in school. The film’s first part, ending roughly after WW II, once again offers students fresh revelations. (Space does not allow me to narrate the entire drama.)

First of all, that the story takes place in western Algeria, which commonly receives much less attention than Algiers, offers opportunities to discuss the fact that more Spaniards settled in the province of Oran than any other ethnic group. Second, the collaboration between local Muslim Arab dignitaries (the caid) and colonial authorities complicates the colonized vs. colonizer divide. In addition, across North Africa during the inter-war period, a rural-to-urban exodus occurred in large measure due to indebtedness in countryside and demographic pressures on the indigenous peasantry. It resulted in enormous bidonvilles ringing cities like Oran, which boasted the largest proportion of Europeans to Algerians, a trend that ultimately produced the initially North African bidonvilles in France. (One could also imagine inserting into class discussions the fact that Oran was the venue for Camus’s 1947 novel, La Peste.) That a “native” like Mohamed the pharmacist was well-educated and well-schooled is another eye-opener. But the most startling realization for student audiences is the marriage between Mohamed and Madeleine for which they endure some social opprobrium. As in La Goulette, the dialogue, at least for conversations between Algerians, switches back and forth from Arabic to French.

Colonial racism episodically rears its ugly head—in the classroom and schoolyard, at the beach, and in the work place. With la rentrée scolaire, we witness the racialized cruelties of children and adults in Franco-Arab schools. In a scene reminiscent of Memmi’s schoolday experiences in The Pillar of Salt, the French schoolmaster reads out the class roll on the first day; one of the pupils is clearly an Arab Jew and Younès or Jonas is revealed to his classmates as Arab and Muslim. Obviously, the problem of naming and prejudice can be unpacked from this incident and tied to present-day realities in France (and elsewhere in Europe). For example: the apparently “non-violent” and petty, but deeply alienating, violations that characterized everyday life in settler colonies. “Racial profiling” in the colonial schoolyard or classroom that so many North African writers evoke in their memoirs lends itself to a discussion of different kinds of race/violence with American students, who themselves may have experienced or witnessed similar profiling. Yet the histories, meanings, and uses of “race” for North Africa complicate this notion (or cluster of taxonomies of difference and social oppression) for students who then can puzzle out the alignment of religion and ethnicity—Maghribi Arab Islam and Arab Judaism—with our home-grown varieties of race.

Colonial racism episodically rears its ugly head—in the classroom and schoolyard, at the beach, and in the work place. With la rentrée scolaire, we witness the racialized cruelties of children and adults in Franco-Arab schools. In a scene reminiscent of Memmi’s schoolday experiences in The Pillar of Salt, the French schoolmaster reads out the class roll on the first day; one of the pupils is clearly an Arab Jew and Younès or Jonas is revealed to his classmates as Arab and Muslim. Obviously, the problem of naming and prejudice can be unpacked from this incident and tied to present-day realities in France (and elsewhere in Europe). For example: the apparently “non-violent” and petty, but deeply alienating, violations that characterized everyday life in settler colonies. “Racial profiling” in the colonial schoolyard or classroom that so many North African writers evoke in their memoirs lends itself to a discussion of different kinds of race/violence with American students, who themselves may have experienced or witnessed similar profiling. Yet the histories, meanings, and uses of “race” for North Africa complicate this notion (or cluster of taxonomies of difference and social oppression) for students who then can puzzle out the alignment of religion and ethnicity—Maghribi Arab Islam and Arab Judaism—with our home-grown varieties of race.

Both films are in the genre of “coming of age,” although Ce que le jour is much more so, in addition to being more dramatic (and explicitly sexy). It is also the tale of improbable love, which La Goulette is not. And the colonial pecking order in Moulessehoul’s novel and Arcady’s cinematic rendition differ from La Goulette. Aside from Jonas’ uncle, the vast majority of Algerians are servants or badly treated laborers. In addition, the standard  colonial “redemption” narrative is alluded to in the scene where the mayor of Rio Salado, a large landowner, extols to his daughter the magnificent agrarian empire that he has created.

colonial “redemption” narrative is alluded to in the scene where the mayor of Rio Salado, a large landowner, extols to his daughter the magnificent agrarian empire that he has created.

The confluence of colonial studies and environmental histories has produced significant insights into “environmental imaginaries.” From circa 1800 on, European travelers and polemicists depicted the Middle East and North Africa as “an ecological disaster zone” whose majority Muslim inhabitants were responsible for agricultural degradation, deforestation, and mismanagement of scarce water resources. Thus, both the land and people needed rescue by outside powers. Ecological redemption stories proved extremely attractive for Euro-North American audiences during the heyday of empire. Regrettably they still inform some “development” driven policy for the region, notably in non-academic circles, and especially for modern Palestine—something American students need to realize.

Nevertheless, both films deal with memory, exile, and nostalgia, currently a critical arena of debate for historians. One potentially fruitful exercise for future courses would be to have students research and compare the life trajectories and political activism of the directors and writers of these films. A major nagging question for all enrolled in the class is what historical elements rendered French colonial Tunisia different from, or similar to, French Algeria. And together these films demonstrate that French North Africa was a lot more complicated than the view from Algiers and Paris. Indeed, as Matthew Connelly pointed out in A Diplomatic Revolution (2002), Algeria was comparatively speaking an anomaly.[8]

In any case, imperialism in its many guises, with its intolerance and violence, and the moral wages of repressed memory and enforced silences, should be imparted to our students—as America’s Middle Eastern empire falls apart and a “new front” in the global terror wars opens in the Chaambi mountains of the Algero-Tunisian border regions.

Férid Boughedir, Director, Un été à la Goulette [Summer in La Goulette], 1996, 100 min, Color, Tunisia, France, Belgium, Canal+, Cinares Production, La Sept Cinéma, Lamy Films, Marsa film, RTBF.

Alexandre Arcady, Director, Ce que le jour doit à la nuit, 2012, 162 min, Color, France, Alexandre Films, New Light Films, Studio 37, Wild Bunch, France 2 Cinéma, Les Films du Jasmin.

- Boughedir co-wrote the script with Nouri Bouzid who was born in Sfax in 1945. Bouzid has produced and/or written a number of internationally recognized films, such as Tunisiennes (Bent Familia, 1997) and The Season of Men (La saison des hommes, 2000). Boughedir is among the best-known critics of the African and the Arab film worlds and author of numerous works. He began his career with documentaries about the new cinema produced in these regions: Caméra d’Afrique and Caméra Arabe, both presented at Cannes. In 1990, his first fictional work, Halfaouine (Boy of the Terraces), also showed in Cannes, delighting critics and audiences alike; until now, it remains one of the biggest successes in Tunisian film history. At the 1996 Berlin Film Festival, A Summer in La Goulette earned several prizes. In addition, Boughedir has served as the director of the oldest Pan-African festival, the Carthage Film Festival, which takes place in the summer, attracting a large and diverse international audience. It should also be noted that Tunisian women, such as Moufida Tlatli and Dora Bouchoucha Fourati, have had excellent film careers.

- Lest the reader wrongly think that La Goulette was spared the systemic venality of the Ben `Ali regime (1987-2011), often in the form of prime real estate seizures, in fact the town began to build sleek, expensive condos near the sea, probably underwritten by Ben `Ali’s international corporate sponsors, French, Italian, etc.

- Born in Kenadsa in the Sahara of southwestern Algeria near the Moroccan border, Mohammed Moulessehoul’s (or Yasmina Khadra) mother was from a Bedouin or nomadic tribe; his father, a nurse by profession, participated actively in the Algerian nationalist army. Educated in military academies, Mohammed served in the post-colonial army for decades. Between 1984 and 1989, he published under his real name six novels that garnered literary prizes but due to censorship he was forced to adopt several noms de plume. His literary and artistic output is staggering and he has been awarded numerous international honors, including a UNESCO prize en 1993. Alexandre Arcady’s life story is equally fascinating. After his family was forced out of Algeria, he became a Zionist and even immigrated to Israel to live in a kibbutz. His first full-length film was autobiographical, Le Coup de sirocco (1979), and was one of the first to address the “expatriate” pied-noir community in France, evoking the pain of expulsion and exile with nostalgic representations of a land lost.

- My heartfelt appreciation to all of my University of Arizona students who have shared their insights on these films with me in class, especially this year’s “History of Modern Mediterranean Migrations” course and the graduate student colloquium, “Women, Gender, and Empire.”

- See my review of “Noyés par balles” (France and Algeria, 1992), directed by Philip Brooks and produced by Alan Hayling, in the Middle East Studies Association Bulletin 37, 2 (2003): 302-03, which can be nicely paired with James House and Neil Macmaster’s Paris 1961: Algerians, State Terror, and Memory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

- In 1948, approximately 105,000 Jews called Tunisia home, although some were refugees from Europe who found haven in North Africa during World War II. With independence from France, Tunisian Arab and Italian Jews did not suffer from explicit property expropriations or expulsion policies but pressures were exerted upon them to leave; many emigrated either to France or Israel; with the 1967 war and Israel’s occupation of East Jerusalem and the West Bank, Tunisian Jewish emigration to France and Israel accelerated. Today, about 1,500 remain mainly in Djerba, Tunis, and Zarzis. A small Italian community remains, mainly around the capital, which publishes a monthly newspaper in Italian; its ranks have been thinned of course by the passage of time.

- This is not the place to engage the debate among historians over the contentious issue of the historical accuracy of films and documentaries in the classroom. However, when I arrived in Tunisia in 1973 as a Peace Corps volunteer—six years after La Goulette’s alleged setting—I found a very similar social universe to the one portrayed by Boughedir and Bouzid.

- Matthew Connelly, A Diplomatic Revolution: Algeria’s Fight for Independence and the Origins of the Post-Cold War Era (Oxford and New York, 2002).