Michael Miller

University of Miami

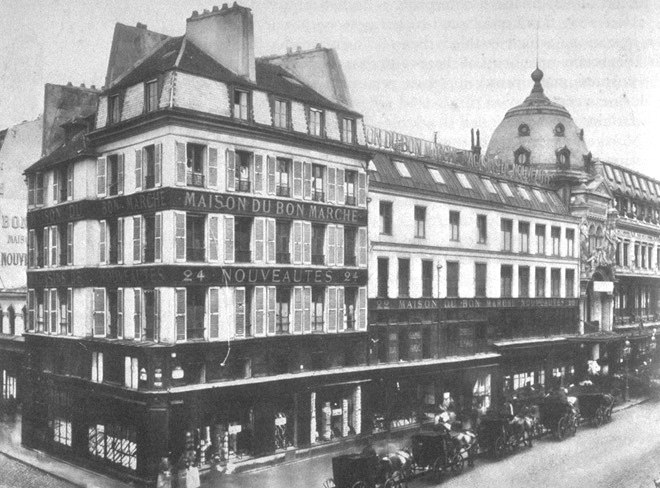

The credits that precede each episode of the BBC’s The Paradise, tell us that the miniseries is based on Émile Zola’s novel Au bonheur des dames. They might as well go on to say that this period-piece soap opera set in a large store in nineteenth-century northern England is no less based on Upstairs, Downstairs, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, and countless episodic historical dramas British television has been producing for decades (with the exception of real masterpieces like I Claudius, or Brideshead Revisited, where great care was taken to carry over to the visual medium the brilliance of the original novel). What The Paradise owes to Zola’s 1883 novel, let alone the history of the rise of the department store, is therefore a question begging rather dubious answers. But before taking this up, it seems appropriate to ask first what the history of the rise of the department store owes to Zola and Au bonheur des dames. The question may seem oddly put, but when I went to Paris to research the history of the Bon Marché my principal source of information, after the store’s own archives, were Zola’s meticulous notes from his on-site visits to the Bon Marché and Louvre department stores that he gathered “to create the poetry of modern activity.”[1] Returning to the novel after what must be at least a twenty-year absence, I still am struck by how deeply his descriptions of his fictional grand magasin resonate of the notes I then took, nearly a century later, from the original carnets on deposit at the Bibliothèque nationale. If the history of the rise of the department store is what we historians have reconstructed from the contemporary sources available to us, then it must be acknowledged that that history is also, in part, Zola’s history.

There is to be sure as much fiction as fact in Au bonheur des dames. Zola set his novel in the 1860s, when Haussmann’s rebuilding of Paris created a city infrastructure favorable to the emergence of large-scale retail shopping. Yet Zola’s visits and notes were from nearly two decades later, when both the Bon Marché and the Louvre were very different, far more sizeable and diverse enterprises than they had been in the last years of the Second Empire. In certain ways, the transactions of Zola’s impresario, Octave Mouret, with the financier Baron Hartmann prefigure the creation of the Louvre Department Store, but the Louvre was a considerably smaller and more haphazard production than the magnificent full-scale Au bonheur that we see constructed and opened to extraordinary success in the second half of the novel. Octave Mouret, the creator of Au bonheur, is a character of Zolaesque origins, predating the writing of Au bonheur, and too much an imaginary assemblage to take for either Aristide Boucicaut or the founders of the Louvre. Denise, the heroine in the novel, takes on certain paternalistic attributes of the legendary Madame Boucicaut, but little else in her portrait would seem to correspond to the little we know of Marguerite Boucicaut.

There is to be sure as much fiction as fact in Au bonheur des dames. Zola set his novel in the 1860s, when Haussmann’s rebuilding of Paris created a city infrastructure favorable to the emergence of large-scale retail shopping. Yet Zola’s visits and notes were from nearly two decades later, when both the Bon Marché and the Louvre were very different, far more sizeable and diverse enterprises than they had been in the last years of the Second Empire. In certain ways, the transactions of Zola’s impresario, Octave Mouret, with the financier Baron Hartmann prefigure the creation of the Louvre Department Store, but the Louvre was a considerably smaller and more haphazard production than the magnificent full-scale Au bonheur that we see constructed and opened to extraordinary success in the second half of the novel. Octave Mouret, the creator of Au bonheur, is a character of Zolaesque origins, predating the writing of Au bonheur, and too much an imaginary assemblage to take for either Aristide Boucicaut or the founders of the Louvre. Denise, the heroine in the novel, takes on certain paternalistic attributes of the legendary Madame Boucicaut, but little else in her portrait would seem to correspond to the little we know of Marguerite Boucicaut.

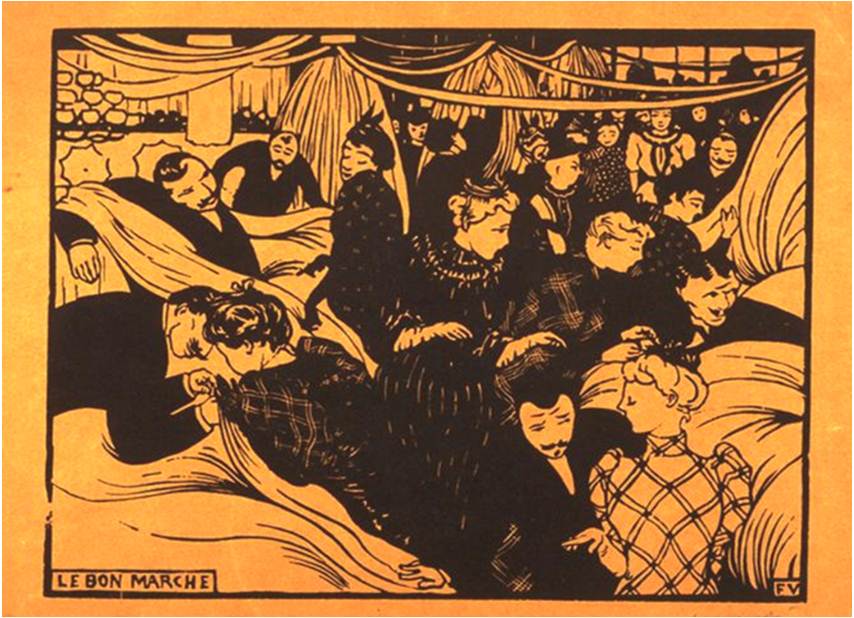

None of this, however, should matter greatly since Au bonheur des dames fails miserably as a purely literary creation. Neither characters nor plot development carry any significant weight. All are filler between the great scenes that concentrate on the one, dominant, and irreducible protagonist: the department store. In his most gifted moments – the days of great sales, culminating in the triumphant White Sale passage that carries the novel to its conclusion – Zola, whose characters are almost all totally forgettable, serves up unforgettable evocations of the flow of crowds, the profusion of goods, the temple of consumption, and the mass worship at its material altars that led him to equate the new department stores (of the 1880s) with cathedrals of the past. This too came straight from his carnets: “the department store tends to replace the church. It marches to the religion of the cash desk, of beauty, of coquetry, and fashion. [Women] go there to pass the hours as they used to go to church: an occupation, a place of enthusiasm where they struggle between their passion for clothes and the thrift of their husbands; in the end all the drama of life with the hereafter of beauty.”[2] There is too the somewhat forced but absolutely essential scene early in the book when Mouret, the great seducer of women, seduces no less than Baron Hartmann as he lays out all the principles of modern retailing. Generate vast profits by rapid high-volume turnover. Price your goods accordingly with lower mark-up. “Sell cheaper to sell a great deal.” Only to sell a great deal understand that your business is seduction, your product consumption. Overwhelm your clientele – women – with fantasy and the irresistible desires that come with shopping. Pile up the goods. Display them to overpower the senses. Raise to women a temple, create out of the pleasure of shopping the “rite of a new religion.”[3]

Mouret utters these words with almost complete contempt for his customers, only, as we discover later, to be reduced to absolute jelly by the humblest (initially) of females. But who cares. The power of the scene belongs not to Mouret but to the store and what it represents. Over many subsequent pages we return to both “mechanisms” and consequences. Mouret excels at creating lures. He masters the use of leader items. He discovers the logic of thinking illogically when appealing to irrational desires. Hence, again straight out of the carnets, he rearranges the order of departments to provoke confusion and exposure to the entire range of the house’s goods. Before his mastery all crumble; even the most honorable and respectable are turned into obsessive shoppers, thieves, or kleptomaniacs. As the new store takes shape Zola takes us on a tour of the “dessous” of the store, the vast bureaucracy of services and offices that underpin the center stage of sales. This too he noted on his visits to the Bon Marché and the Louvre. Reflecting on the aftermath of a great sale, Zola likens it to “a battlefield still warm from the massacre of fabrics.”[4] In the archives of the Bon Marché can be found the Karcher letters, written by house secretary Jean Theodore Karcher to Madame Boucicaut, who was often away from Paris in the 1880s. Karcher too uses military images: “It makes me proud to march in the ranks of a peaceful army that knows how to reap such victories.”[5]

The subplots that revolve around Denise – her ill-treatment by the other shop girls; the working and personal lives of women clerks (who numbered only about 150 out of the 2500 employees at the Bon Marché when Zola arrived in the early 1880s); the reign of the Lhommes and especially the overriding presence of Madame Aurélie, a department head who makes far more money than Mouret’s sad childhood friend and offspring of the “petite noblesse ruinée;”[6] or Denise’s ties to the old commerce whose principle is “not to sell a great deal, but to sell dear,”[7] and who are crushed by Mouret’s grand creation – are all extensions of Zola’s desire to showcase the poetry of modern activity, blemishes and all, as he has found it. With the exception of his overwrought detailing of the decline of the Baudus and Bourrases, rarely – when focusing on the store itself – does he cross the line between fictional re-creation of an observed reality and excessive portraiture for dramatic effect. How well the novel will go down in the classroom is uncertain: it is after all a long book with, frankly, many boring passages. Still, Zola got most of it right, and without his notes, or his powerful sales scenes, we would be much the poorer.

Can we say the same of The Paradise? On the surface of things there are clear parallels. The name comes straight from the English translation of Au bonheur des dames, or The Ladies’ Paradise. The two principal characters are Denise and John Moray, phonetically about as close as one can come in English to the original. Madame Aurélie is Miss Audrey. Inspector Jouves, who is a minor figure in Zola’s concoction but a looming presence in this version, is named Jonas, on the premise one might suppose that a first letter or two indicate good faith. The location is transferred from Paris to northeastern England, not as strange a choice as might at first seem. London lagged behind Paris and New York, and arguably the first department store in Britain was Bainbridge’s of Newcastle upon Tyne.[8]

Can we say the same of The Paradise? On the surface of things there are clear parallels. The name comes straight from the English translation of Au bonheur des dames, or The Ladies’ Paradise. The two principal characters are Denise and John Moray, phonetically about as close as one can come in English to the original. Madame Aurélie is Miss Audrey. Inspector Jouves, who is a minor figure in Zola’s concoction but a looming presence in this version, is named Jonas, on the premise one might suppose that a first letter or two indicate good faith. The location is transferred from Paris to northeastern England, not as strange a choice as might at first seem. London lagged behind Paris and New York, and arguably the first department store in Britain was Bainbridge’s of Newcastle upon Tyne.[8]

In a “Behind the Doors” extra that comes with the DVD series, Melanie Allen, the production designer, says that although Zola’s novel was written in the 1890s (actually it appeared in 1883) the production crew decided to set The Paradise in the 1870s; yet it would be difficult to quarrel with such a decision since Zola also transposed his 1880s version of the department store to the 1860s. The series, moreover, benefits from all the technical brilliance that British TV is accustomed to bringing to its historical re-creations. The look of the show is nothing less than stunning. Melanie Allen’s set, built wholesale in County Durham, is magnificent in its colors, lighting effects, and textures. The costume designs are taken from Tissot paintings. Great care is taken with hair styles, although, we are told, there are also a few liberties to accommodate present day romantic aesthetics.

Unfortunately, that is only the beginning of the “liberties.” About half way into the first episode it becomes clear that one need not worry about faithfulness to the novel; there simply is not going to be much. Joanna Vanderham’s Denise, upon arrival at the store, looks nothing like what one imagines of Denise in Au bonheur. This Denise is far too self-assured, far too attractive from the start. The store looks nothing like Au Bonheur des Dames. It is far too small, with too few employees, and remains so through the remainder of the series. The Paradise borrows from Zola the theme of financial intrigues over store expansion. But whereas in Au bonheur this leads to the evolution of the store into a giant commercial machine, in The Paradise it becomes a plot device for telling trivial stories to fill out an hour: either of ridicule and murder of a barber who won’t sell out to Moray unless he is brought in as a partner, or the fatherly machinations of Lord Glendenning to coerce Moray into marrying his daughter Katherine (the Henriette Desforges of the novel; Lord Glendenning is this version’s Baron Hartmann). The Paradise retains Zola’s subplot of the demise of small shopkeepers, only in this show another subplot then develops: the old-flame connections between Audrey and Edmund Lovett, Denise’s uncle, flickering up again at various points throughout the later episodes. Here and there in the episodes Moray utters a sentence or two about the new culture of shopping: “Need,” Moray tells Lord Glendenning, “is not the issue, sir. I deal in appetite.” But whereas Zola went to pains to illuminate, through dialogue or dense description, the mechanisms of modern commerce, here such a concern is far less interesting than creating a mystery about the death of Moray’s first wife and maneuvering plot twists around dead bodies washing up in the river. Even when an opportunity to crawl back into the world of nineteenth-century retailing is handed to the scriptwriters on a platter, they take a pass. In the final episode, Moray gathers his personnel to tell them that he wishes he could invite all of them to his wedding but the store must remain open and only a few representatives will be present. The Boucicauts would never have let slip such a symbolic opportunity to bind their retinue to the store.

Perhaps where the show is most faithful is in its comprehension that sex sells. Zola’s store evocations are bathed in sexuality. Mouret triumphs in his gifts as a seducer of women, and they all, to man or store, succumb in the end. The long panoramic gazes over the merchandise for sale are suffused with the sensuality of fabrics and textures, registers to the touch, references to the flesh, imaginings of female intimacy. As the “fever” of the great White Sale at last comes to an end, “money rang in the cash boxes while the clientele stripped bare (dépouillée), violated, went away half defeated, with the quenched voluptuousness and secret shame of a desire satisfied in the depths of a hôtel louche.”[9]

In The Paradise, beneath the constraining but gorgeous costumes, lurks a sexuality in language, mood, looks, touches. Moray too is a seducer. In Victorian England there can be no open sex scenes. To compensate, Moray and Denise drum up the idea of “Ladies Night Out”: a special, showing of women’s lingerie modeled by the shop girls, an evening to be done in secret, shrouded in an air of mystique, to heighten the pleasure.

But neither Zola nor the Parisian department store are much of a source for this show. Its derivations lie elsewhere, perhaps most of all in the episodic, multiple subplot, quick scene-shift style of the instant information flow age, that rival ITV has deployed with great commercial success in its period-piece, Downton Abbey. Looking for a competitor, BBC obviously dug deep into the British repertoire. Britishness, not Frenchness, must do. Thus far more than Au bonheur des dames, Upstairs, Downstairs is the model for The Paradise as we swing from the lives and loves of the help (now paradoxically upstairs) to the fraught dramas of Moray and the Glendennings. There is also a strong pinch of Miss Jean Brodie added to the stew via Sara Lancashire’s interpretation of Audrey. “Girls,” she is forever issuing in the homilies and commanding tones of Maggie Smith to the shop assistants. “Child [in high broad tones],” she tells Denise who has confessed she has fallen for ‘John,’ “ you’re doomed . . . feelings pass if we do not act upon them. If, however, you stray into that treacherous world of divulgence . . . .” The implication is that for all her possibilities – in this show Denise comes up with all the bright ideas – indiscretion will foreclose advancement.

In Zola’s novel all scenes, save the clerks’ outing to Joinville on the Marne, take place in Paris, mostly in the store or the small shops across the street or in Henriette Desforges’s salon. But in a British show there must be country houses and greenery, and hence the Glendennings. To make the hesitant Moray jealous, Katherine accepts courtship from Peter Adler, which sets up more countryside scenes. Moray and Denise meet in parkland, or on bridges, more opportunity for gorgeous countryside visuals. British TV must also be about class. Hence the pervasive Upstairs, Downstairs motifs. But in the twenty-first century, class must accord with contemporary anti-elitism. So Moray is forever true to his class origins (if probably not to history). When the happy-go-lucky clerk Sam – another BBC add-on who is to Zola’s Hutin as British chips are to pommes frites – is trapped into a compromising situation with one of Katherine’s neurotic friends (more opportunity for country house scenes), and Lord Glendenning demands his dismissal. Moray honorably stands by Sam, just as Sam retrieves honor while treated dishonorably by his “betters.” Moray, like Mouret, will fall completely for Denise and abandon Katherine as Mouret foregoes Henriette. But Zola would never think to have Mouret tell his sidekick Bourdoncle (whose re-creation as Dudley is a far more sympathetic character), that he wants a delivery boy to be one of his grooms at his wedding because he never wants to forget where he came from. Just as contemporary sentiments must be assuaged, Denise must be converted into the modern woman who asserts herself and her initiatives at every turn. It might be said that Denise never had an idea that Moray didn’t like. There is a great deal of gender history that can be extracted from Au bonheur des dames. Yet this portrait of Denise can scarcely be said to conform to what Zola noted of the demoiselles when he went to the Bon Marché and Louvre.

Whereas for Zola the romance of Mouret and Denise was the background noise to the celebration of the department store, in The Paradise, the store becomes merely the occasion for creating next week’s plot twists, such as Sam gets in trouble, or Audrey’s ego is bruised, or what to do about a foundling child deposited at the store – the one opportunity for Moray to mouth Zola’s church metaphor, although in a bastardization of what Zola had in mind. Never is the departure so apparent as in the turn to two more old standbys, the detective story qua gothic horror film. Hovering over this show is the innuendo surrounding the death of Moray’s wife, and the menacing figure of Jonas, marvelously played by David Hayman (just as Patrick Malahide commands every scene that he is in as Lord Glendenning). Jonas is the voice beyond the grave. Bradley Burroughs can attest to that, until he exchanges roles, of sorts, and washes up to sink Jonas. But by this time, Jonas has told his story, a triumph over adversity, which makes him a more lovable, if far less interesting and defanged specter in the show. All of which brings us back to the mechanisms of modern commerce. The Paradise, in its own way, is all about them. The only problem is: what happened to the department store?

Émile Zola, The Ladies Paradise, Oxford World’s Classics, 2008.

Bill Gallagher, Director, The Paradise, Series 1, 2012, 470 min., UK, English, BBC Drama Productions. DVD released in USA, 12 November 2013.

- Émile Zola, Notes for Au bonheur des dames, Bibliothèque nationale, NAF10277, p. 2.

- Ibid., pp. 88-89.

- Émile Zola, Au bonheur des dames (Paris: Le Livre de Poche, 1960), pp. 89, 92

- Ibid, p. 139.

- Bon Marché Archives, Karcher letters, 8 February 1887.

- Zola, Au bonheur, p.77.

- Ibid., p. 29.

- Bill Lancaster, The Department Store: A Social History (London: Leicester University Press, 1995), 7.

- Zola, Au bonheur, p. 498.

Having only seen two episodes so far of “The Paradise,” I’m not the best person to lead a discussion of it, but I am familiar with Zola’s “Le Bete Humain” which is about Paris trains and train stations, mechanisms similar in symbolic stature to department stores. Zola was one of the first 18th century naturalists who often dealt with reality as mechanism, but for the reader, mechanism becomes a boring topic quickly, and the variations of its subplots can be imagined all too easily whether of trains or department stores, and thus it is understandable the writers abandoned Zola’s ‘script’ and pursued more social-psychological themes.

19th c. Zola b. 1840.

After watching on Netflix the first 6 episodes of the Paradise I was filled with unease. The story didn’t ring true, starting with the main character Moray. This couldn’t be a Zola story. It was too “rose-water”. Curious, I acquired Au Bonheur des Dames and am half way through it. What a difference! Zola insight into the world of greed and commerce is so right on, so modern. Underneath all the exhaustive (and exhausting) descriptions of the Bonheur, he is talking about the corporations of today, about their cynicism, their reach for increasing power. Replace all the manual labor—-which makes the Bonheur des Femmes such a well oiled machine—-with computers and automation, and you have Amazon! In my little town I have seen a new mega store wiping out a small family business. Reality doesn’t make for uplifting and pleasing fantasies. Why not just make up a new story instead of passing fluff for an Emile Zola?