Charles Rearick

University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Emeritus

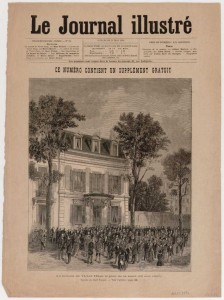

Despite the title Victor Hugo is not yet dead as the novel opens. He is dying … slowly. Crowds of Parisians–workers, students, diverse admirers of the poet and republican stalwart–gathered for the deathwatch outside his apartment building. Dignitaries came to pay respects, and newspapers announced his demise–erroneously. He hung on … for days, long days and nights.

He doesn’t die until page 35. Up to that point in the book, the novelist unfolds the backstory. The eighty-three-year old Hugo had caught a cold in late April 1885, and it had developed into a more serious illness. Three weeks into May, the end appears to be approaching. His family members living with him–grandchildren Georges and Jeanne, and their mother Alice (widow of son Charles Hugo), now wife of Édouard Lockroy–worriedly follow his condition day and night. While chronicling the days of the agonie, the storyteller deftly enlarges the cast of characters, introducing Parisians of diverse social and political milieus. She also moves the focus from Hugo’s street in the beaux quartiers to working-class areas of the city–and then back again.

The street in front of the apartment building is thronged with admirers of the poet and a variety of political groups–republicans, socialists, anarchists, Bonapartists. In other parts of the city, militants gather in meeting halls and cafés and debated–often passionately–the action they should take to pay homage, demonstrate, or protest on the day of the funeral.

Recounting these days of waiting and planning, the novelist maintains a sense of drama and suspense. Uncertainty reigned for weeks, along with fears and intrigue. The uncertainty involved much more than not knowing when the hero’s death would come. How would the people of Paris respond when it finally happened? The fear of “disorder” comes up in the very first line of the novel. The government and police worry that crowds would erupt in a riot or rebellion or revolution. And fear of anarchist bombs runs through the story. Police spies (indics, mouchards) attend all the radicals’ political meetings to learn of troublemaking plans being hatched.

Will the great man call in a priest for last rites? The public awaiting Hugo’s decision did not view it as a strictly personal one. To the republican heirs of the Enlightenment, the refusal of a religious rite would be a national hero’s confirmation of rational progress–free of clergy and superstition. To the faithful of the Church, Hugo’s calling a priest in would be a symbolic turn back to the church and France’s historic faith.

Medical reports grew more dire on the 21st of May: groans and convulsions, organs shutting down. Finally, on May 22 at 1:27 p.m., Hugo raised his head a last time and then fell back on the bed, dead. The following day (May 23), the National Assembly expressing unanimous veneration of Hugo the poet, voted to give him a grand national funeral, at state expense. Nothing close to consensus, however, existed regarding his political stances through the years, particularly regarding the Commune.

Medical reports grew more dire on the 21st of May: groans and convulsions, organs shutting down. Finally, on May 22 at 1:27 p.m., Hugo raised his head a last time and then fell back on the bed, dead. The following day (May 23), the National Assembly expressing unanimous veneration of Hugo the poet, voted to give him a grand national funeral, at state expense. Nothing close to consensus, however, existed regarding his political stances through the years, particularly regarding the Commune.

A thicket of divisive issues stirred public debate for the next ten days. When would the funeral take place? Where would the burial be? Père-Lachaise or the Panthéon? If the Panthéon, it would have to be desacralized, once more turned into a “temple of great men.” What route would the cortege take? Who would be admitted to witness the rituals–at the Arc de Triomphe, along the procession route, and at the Panthéon? Would the big day occasion a rising of the misérables and revolutionaries? Under a red flag or a black flag? Would the police and their spies use the occasion to conduct thorough repression, firing on crowds and arresting dissidents? Each decision meant choosing one side or the other in the great socio-political divide of the era: siding either with the workers, the “humbles,” “les petits” or taking the side of the bourgeois, the rich and powerful.

The workers’ representatives wanted the funeral to be held on a Sunday, when everyone would have a day off, not a Monday, especially if Monday were not made a holiday. The government decided for Monday. Workers and their spokespersons wanted the procession to go through the popular quarters of the Right Bank (passing the symbolically charged Place de la République, for example) and burial in Père Lachaise, where anyone could enter without admission charge. Those in power decided on burial in the Panthéon, and they limited the procession’s route to the Left Bank.

Partisans of the Commune, including a sizable number of ex-Communards, respected Hugo for his opposition to the Second Empire, his patriotic devotion to France, and his advocacy of amnesty for the Communards, but they also remembered that he did not support the Commune during the fierce battles in the streets. In the end he was “bourgeois,” despite his humanitarian sympathy for the “misérables.”

On Sunday May 24, two days after Hugo’s death and fourteen years after the bloody final massacre in Père-Lachaise cemetery, the Commune sympathizers marched to the Mur des Fédérés for their annual commemoration. Skirmishes with the police ensued, ending in numerous arrests and injuries. For the narrative those violent incidents demonstrate the still explosive potential of the Commune and give a sense of heightened tension in the week leading up to the funeral.

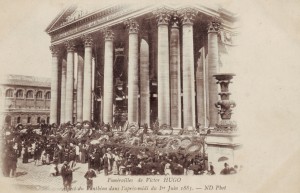

The national funeral itself, on Monday June 1, turns out to be anticlimactic. Disorder did not break out. Everything went as planned: the ceremony at the Arc de Triomphe, the procession across the bourgeois boulevards of the Left Bank, and the entry into the Pantheon. Authorities and the police successfully controlled the day’s events —to the benefit of the state and placeholders on all levels of government who had choice seats. The police seized some red flags and black flags along the procession route and made a few arrests, but no great trouble erupted. “The crowd” disappointed the dreamers of revolution. Ordinary people watched the spectacle and enjoyed it. They did not weep. They laughed. The crowd did not challenge the Republic’s powerful establishment. “The people” did not question the era’s underlying historical philosophy–the belief in progress–and even viewed France’s colonial expansion through that lens as they gawked at exotic colonial representatives who had come to Paris for the funeral.

The national funeral itself, on Monday June 1, turns out to be anticlimactic. Disorder did not break out. Everything went as planned: the ceremony at the Arc de Triomphe, the procession across the bourgeois boulevards of the Left Bank, and the entry into the Pantheon. Authorities and the police successfully controlled the day’s events —to the benefit of the state and placeholders on all levels of government who had choice seats. The police seized some red flags and black flags along the procession route and made a few arrests, but no great trouble erupted. “The crowd” disappointed the dreamers of revolution. Ordinary people watched the spectacle and enjoyed it. They did not weep. They laughed. The crowd did not challenge the Republic’s powerful establishment. “The people” did not question the era’s underlying historical philosophy–the belief in progress–and even viewed France’s colonial expansion through that lens as they gawked at exotic colonial representatives who had come to Paris for the funeral.

The authorities succeeded in appropriating Hugo’s life and works for their purposes, making the funeral a ceremonial moment of national unity, nationalist pride in French culture, and homage to a hero of the Republic. They left out the Hugo who voiced the anger of “the people” and the defiant intellectual who was outlawed and exiled. Amidst the grandiose pageantry organized by the powerful, only the pauper’s hearse he had insisted on stood as a testament to his commitment to the commoners, the luckless, the dominated.

The Novelist’s History and the Historian’s

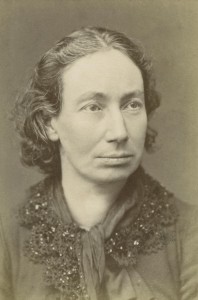

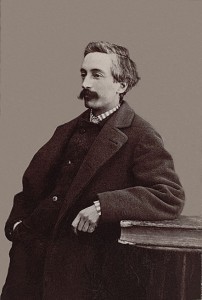

Considerable research went into writing this novel. The novelist used accounts by historians, newspaper reports, and archival police records. The main characters are well- documented historical figures: Hugo’s family members; former Communards Maxime Lisbonne, Prosper-Olivier Lissagary, and Louise Michel; minister of the Interior François-Henri Allain-Targé and Prefect of Police F.-A. Gragnon. The newspapers and political organizations mentioned are also authentically historical. Overall, the novelist has reconstructed the main lines of a documented history.

Many minor characters, however, are fictional, added as representatives of a group. (So a couple of workers from the Faubourg Saint-Denis stand in for the Parisian working-class.) Small incidents, too, are made up–to tell what one character might have said to another–for example, the exchange (p. 50) between Lisbonne and Targé in a café about the minister’s control of the electoral committees of Belleville.

But the big drawback in the historical fiction genre, of course, is that the reader likely does not know which details and characters are simply made up and which are not. For example, (p. 44) the mention of “Les quarante mille cadavres de la Semaine sanglante!” appears to refer to an accepted statistic (without any footnote, of course). Historians now estimate a far lower number and suggest that all such accounting is problematic.[1] Also troubling–to historians, at least–are the anachronisms that the novelist slips in occasionally: for example, when one character refers to the times as “la belle époque,” (p. 218) a reflexive period-defining term that did not appear until long after the First World War.[2]

Still, one might well ask: what elements of truth might the novelist bring out about the past that a historian might not capture so well? For the funeral of Victor Hugo, historian Avner Ben-Amos has given us an excellent history, a chapter in the Lieux de mémoires.[3] So why bother reading the novel? Can a novel convey understanding of a historical event that a historian’s account does not?

First, the writer of historical fiction is free to fill in the emotions and thoughts of different political groups and individuals–a range of complex subjectivities and responses that cannot be documented by historical records. The public mood surrounding Hugo’s death, the storyteller shows, was not simply sadness. There was excitement, even a strange joy in being lifted out of banal everyday life. For about two weeks leading up to the funeral, the novelist shows, people lived in anticipation of an epoch-making death. The novelist’s description of those people–freethinkers, workers and union-members, students, foreigners, republicans of different stripes, along with spectators in the streets–succeeds in conveying the breadth and strength of Hugo’s appeal and importance. They knew they were witnessing the passing of a history-making hero, and they believed they had a chance to participate in a momentous event. Most wanted the national funeral to reflect their own high hopes for France. But the novelist also portrays the people’s inherent fondness for spectacle and the boom of petty moneymaking ventures–selling souvenirs and places for parade viewers. More strangely, the night before the panthéonisation the sense of a festive break with everyday norms took the form of a widespread orgy, briefly recounted in the novel.

First, the writer of historical fiction is free to fill in the emotions and thoughts of different political groups and individuals–a range of complex subjectivities and responses that cannot be documented by historical records. The public mood surrounding Hugo’s death, the storyteller shows, was not simply sadness. There was excitement, even a strange joy in being lifted out of banal everyday life. For about two weeks leading up to the funeral, the novelist shows, people lived in anticipation of an epoch-making death. The novelist’s description of those people–freethinkers, workers and union-members, students, foreigners, republicans of different stripes, along with spectators in the streets–succeeds in conveying the breadth and strength of Hugo’s appeal and importance. They knew they were witnessing the passing of a history-making hero, and they believed they had a chance to participate in a momentous event. Most wanted the national funeral to reflect their own high hopes for France. But the novelist also portrays the people’s inherent fondness for spectacle and the boom of petty moneymaking ventures–selling souvenirs and places for parade viewers. More strangely, the night before the panthéonisation the sense of a festive break with everyday norms took the form of a widespread orgy, briefly recounted in the novel.

While painting a Brueghel-like canvas of a city multitude, the novelist shapes the narrative by simplifying a mass of details and opinions more than the historian does, concentrating on selected figures to make a more focused, easier-to-follow narrative. One such figure is Édouard Lockroy, who stands out in the novel as a central figure, important both in the family and in the Chamber of Deputies. He is a utility character who can recall earlier times with the great man and his children,in the private realm and who also witnesses close-up the political fissures in public life–in the Assembly, for example, the day when deputies on both the right and left, rail against the government’s decision to transform the Panthéon for the finale. At Hugo’s home Lockroy reads piles of letters addressed to him as political leader and representative of the Hugo family, and where, day after day, he receives dignitaries and delegations coming to visit the dying man.

While painting a Brueghel-like canvas of a city multitude, the novelist shapes the narrative by simplifying a mass of details and opinions more than the historian does, concentrating on selected figures to make a more focused, easier-to-follow narrative. One such figure is Édouard Lockroy, who stands out in the novel as a central figure, important both in the family and in the Chamber of Deputies. He is a utility character who can recall earlier times with the great man and his children,in the private realm and who also witnesses close-up the political fissures in public life–in the Assembly, for example, the day when deputies on both the right and left, rail against the government’s decision to transform the Panthéon for the finale. At Hugo’s home Lockroy reads piles of letters addressed to him as political leader and representative of the Hugo family, and where, day after day, he receives dignitaries and delegations coming to visit the dying man.

Most importantly for a student of history, the novel succeeds in illuminating the social and political fractures in France of the early Third Republic. Through the prism of Hugo’s final days and the national funeral, the novel shows vividly how divided the French were in their attitudes toward the Republic and how polarizing the Commune still was–on one side, an undying devotion (on the part of former Communards, socialist revolutionaries, and anarchists), and on the other, unremitting fear and revulsion.

And the novelist’s account of the Panthéon transfer artfully dramatizes the emotional dimension of republican anticlericalism. After a last mass, when the abbé turns over the church keys to a city official, a jubilant crowd cheers. In a “great moment of collective impiety” (p. 138), some of them go into the confessionals “to smooch,” and some spit in the holy water fount. On the roof five workmen with metal cutting saws (bons républicains, without any fear of going to hell) take down the big iron cross from the pediment. When a well-dressed man loudly deplores the desacralization, the crowd attacks him, until police intervene to stop the brawl.

Finally, in an untitled epilogue, the novelist connects the past with the present and makes critical judgments in an unabashed way that most historians would be reluctant to do. Through the official apotheosis of Hugo, she concludes, the Republic stifled l’homme révolté. Successor republics also shackled his lofty rhetoric and repressed utopian idealism. The fine rhetoric of Hugo, la phrase, lives on in contemporary French culture, to be sure, but people in our time are less naïve and tender-hearted, less open to generous dreams of happiness and justice for all–“un songe trop grand, trop beau,” given human nature. So the novel ends on a note of nostalgia and disillusionment–a view of history as tragedy. Yet the novel’s last sentences, evoking the author’s father and his ideals inherited from the nineteenth century, hint at a final appreciation of the old utopian hopes, held in reverential memory as “the only prayer” that her father taught her.

Judith Perrignon, Victor Hugo Vient de Mourir. Paris: Éditions de L’Iconoclaste, 2015.

NOTES

- See Robert Tombs’s paper “How bloody was la Semaine Sanglante? A Revision” – H-France: www.h-france.net/Salon/Salonvol3no1.pdf as well the commentary and Tombs’s response. H-France Salon, vol. 3, issue 1. The papers originated in a Society for French Historical Studies Conference Panel titled “Communal Myths?” 12 February 2011: http://h-france.net/Salon/h-francesalon.html

- I have traced the origins of the period concept “the belle époque” as it evolved through the 1930s and 1940s–and not before that time. See chapter two of my book Paris Dreams, Paris Memories: The City and Its Mystique (Stanford, Cal.: Stanford University Press, 2011). Dominique Kalifa has a work in progress that also shows the period label “belle époque” emerging much later than in the years right after the Grande Guerre.

- Avner Ben-Amos, “Les funérailles de Victor Hugo”, in Pierre Nora, ed., Les Lieux de mémoire, tome I: La République, pp. 473-522 (Paris: Gallimard, 1984).