Michael Wolfe

St. John’s University

Working as I do for a Catholic and Vincentian university, I encounter the abiding influence of Vincent de Paul almost every day. As an early modernist, I also know that no individual epitomized the new, more socially-engaged Catholic activism in seventeenth-century France better than he.[1] Together with Louise de Marillac, Vincent initiated sweeping changes in how the Church, the Bourbon state, and the aristocracy dealt with the vast poverty and suffering that afflicted so many men, women, and especially children during this “century in crisis.”[2] For their sainted labors, the Church canonized Vincent in 1737 and Louise only much later in 1934. Vincent’s ability to mobilize resources and then marshal them to organize Catholic charities on an unparalleled institutional scale, beginning with Saint-Lazare seminary and hospital, marked a decisive moment in the development of the modern Catholic Church and, in time, the French welfare state.

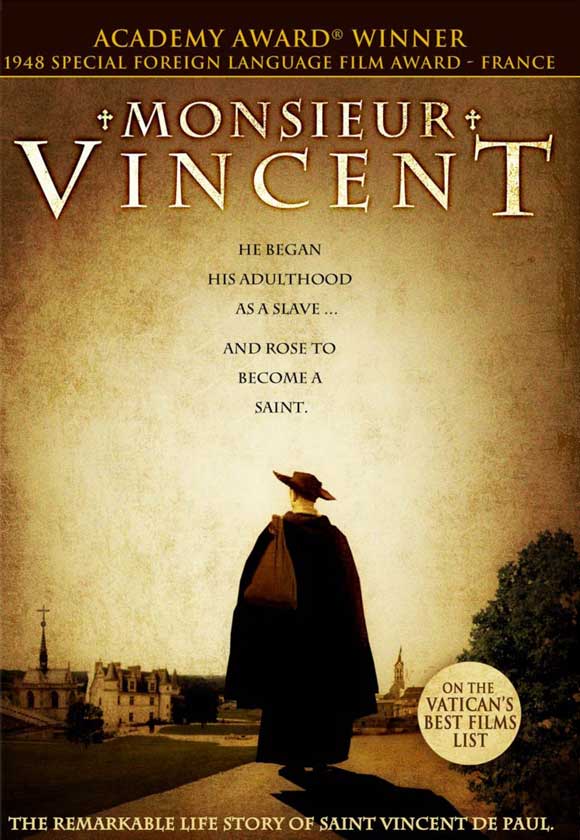

A digitally remastered DVD of the original 1947 award-winning biopic on Vincent de Paul was recently released by Lionsgate/StudioCanal. Directed by Maurice Cloche, Monsieur Vincent won the Special Achievement Academy Award, a precursor to the Best Foreign Film Award, at the 1948 Academy Awards in Hollywood, largely thanks to the superb performance by Paul Fresnay, who brings Vincent vividly to life. Gorgeously shot by Claude Renoir, best known for his cinematography in La Grande Illusion (1937), which also featured Fresnay, and with a screenplay by the noted dramatist Jean Anouilh, Monsieur Vincent offered a redemptive message of Christian love and reconciliation to French audiences just a few short years after the traumas of the Occupation and Liberation. Indeed, as I watched the film, I thought about the actual moment of Monsieur Vincent in postwar France, and will relate some of those musings in this review.

A digitally remastered DVD of the original 1947 award-winning biopic on Vincent de Paul was recently released by Lionsgate/StudioCanal. Directed by Maurice Cloche, Monsieur Vincent won the Special Achievement Academy Award, a precursor to the Best Foreign Film Award, at the 1948 Academy Awards in Hollywood, largely thanks to the superb performance by Paul Fresnay, who brings Vincent vividly to life. Gorgeously shot by Claude Renoir, best known for his cinematography in La Grande Illusion (1937), which also featured Fresnay, and with a screenplay by the noted dramatist Jean Anouilh, Monsieur Vincent offered a redemptive message of Christian love and reconciliation to French audiences just a few short years after the traumas of the Occupation and Liberation. Indeed, as I watched the film, I thought about the actual moment of Monsieur Vincent in postwar France, and will relate some of those musings in this review.

Rather than tell Vincent’s story from the beginning, the film picks it up nearly midway through his life in 1617 when he quit the service of his patron, Philippe-Emmanuel de Gondi, to become curate of Châtillon-les-Dombes in Bresse. Allusions in the film to Vincent’s own peasant origins in Gascony, where he was born in 1580 (or possibly 1576), and prior experiences as a slave in the hands of Barbary pirates, then as almoner to Queen Marguerite de Valois and Madame de Gondi, help explain both his commitment to poor unfortunates and his influence in Parisian high society.[3] Cloche and Anouilh showcase in loose chronological order the evolution of Vincent’s mission to get others to recognize the humanity and dignity of the poor and express love rather than contempt toward them by tending to both their material and spiritual needs. The film frames this leitmotif very effectively in the opening scene as Vincent arrives in Châtillon to find the parish church abandoned and residents, fearing plague, huddled in their houses. As the villagers hurl stones and epithets at him, Vincent discovers and buries a dead woman and saves her starving daughter. His selfless acts of charity and preaching restore faith among the villagers, rich and poor alike. In the real Châtillon, however, the problem was not plague but rather Protestants. It’s understandable that the filmmakers decided to avoid presenting a historical situation that might serve only as a painful reminder of the fateful divisions of the late Third Republic and the ensuing Vichy years. In fact, the religious conflicts roiling seventeenth-century France—dealing with the Huguenot minority, the rise of the dévots and Jansenism, disputes with Rome and the Jesuits—find little place in the film beyond a passing reference to the Council of Conscience, a powerful advisory body to the crown for religious affairs on which Vincent de Paul served in the 1640s.

Pierre Fresnay-Monsieur Vincent (1947) by francomac

After the opening, the movie presents a pastiche of scenes emblematic of Vincent’s struggle to organize what, in time, became the Congregation of the Mission, the Ladies of Charity, and, finally, the Daughters of Charity.[4] Of these three groups, the priests he helped to train in the Congregation of the Mission and who took up local leadership of his movement, first in France and then abroad, receive virtually no mention at all. Only one other cleric, Abbé Portal (played by Jean Carmet), is depicted and serves as a stand-in for the legions of priests who helped to translate Vincent’s vision into reality. The film also undervalues Vincent’s business acumen and adds false drama when he receives notice that he’s behind on the rent at Saint-Lazare and faces eviction. If there’s one practical talent Vincent had in abundance, it was the ability to raise money, though, admittedly, he often said he never had enough for all his ambitious plans. Vincent was, in point of fact, a sort of Steve Jobs (minus the arrogance) for Catholic charities in his day, a man who networked relentlessly, not the lonely heroic figure struggling against all odds fabricated in the film.[5]

The two female orders receive much more attention, beginning with the Ladies of Charity led by Louise de Marillac, who is played by Yvonne Gaudeau, a leading stage actress at the Comédie-Française. While the film stresses the importance of these aristocratic women in funding the charitable foundations that Vincent established, it exaggerates their supposed class prejudices and feminine frivolity. Indeed, a moving scene toward the end of the film sees Vincent cradling a foundling in his arms as Louise and other Ladies of Charity recoil in repugnance from this “fruit of sin.” In reality, although a member of one of France’s most powerful families, Louise de Marillac was herself born out of wedlock. Moreover, the Ladies of Charity fully embraced the organization and funding of foundling hospitals, which would care for some 4000 infants. The film also attributes the establishment of the Daughters of Charity to Vincent in a scene when a country girl, newly arrived in Paris, asks if she can help him with his work. Again, it was Louise who, recognizing the time constraints and lack of practical experience among the Ladies of Charity, took in young farm girls who had the energy and ability to handle the day-to-day operations of the various charities. I could not help but think of what Simone de Beauvoir might have thought about the diminished role of Louise de Marillac in Monsieur Vincent, especially since her Le deuxième sexe appeared just two short years after its release.[6] The historic and central role that women played in charitable work and the caring professions in France has since been recognized by scholars. [7]

That said, Monsieur Vincent does treat questions of class and power quite effectively. In one scene, Cardinal Richelieu, portrayed by Aimé Clairond, summons Vincent to tell him he has been appointed by the king as chaplain to royal galleys.[8] Richelieu makes clear that while his motive to serve the king differs from Vincent’s desire to serve God, they were in the end quite compatible. Missing in the film is the more significant relationship that Vincent had with Queen Anne of Austria and the other cardinal, Mazarin, who despised him. Similarly, Vincent’s call to the aristocracy to take up the cause of charity and embrace the humanity of the poor, though adopted by only a few, nevertheless marked a revolution in attitudes that resonates down to this day. Yet Vincent—both in film and in real life—stopped well short of questioning the social causes of poverty apart from war, choosing instead, quite pragmatically, to work through the established hierarchies in his world. In the end, the relief of physical suffering and identification with the poor principally served the purpose of saving souls, as the film makes clear.

Monsieur Vincent is well worth watching and readily lends itself to classroom discussions as much for what it portrays about the real Vincent de Paul, which for the most part it gets right, and for its various anachronisms. Paul Fresnay’s brilliant performance stands out along with the talented ensemble cast and combines with the film’s strong production values to create a compelling, if somewhat straitened [?] portrait of a man who led the way in the contentious and painful transformation of Catholicism after the shock of the Reformation.

Maurice Cloche, director, Monsieur Vincent (1947), 111 minutes, Black and White, Edition et Diffusion Cinématographiques [E.D.I.C], Office Familial de Documentaire Artistique [O.F.D.A.], Union Générale Cinématographique [U.G.C.], Lionsgate/StudioCanal.

- For an excellent introduction to this subject, see Joseph Bergin’s Church, Society, and Religious Change in France, 1580–1730 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009).

- Eric Hobsbawn developed this thesis in several articles that tellingly appeared a few years after the film’s release. See his “The General Crisis of the European Economy in the 17th Century: I,” Past & Present, no. 5 (May 1954), 33 – 53; and “The Crisis of the 17th Century: II,” no. 6 (November 1954), 44 – 65. Republished as “The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century,” in Trevor Aston, ed., Crisis in Europe, 1560 – 1660: Essays from Past and Present (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1965), pp. 5 – 58.

- Bernard Pujo’s Vincent de Paul, the Trailblazer, translated by Gertrud Graubart Champe, (Notre Dame, Ind.: Notre Dame University Press, 2003), originally published in Paris by Albin Michel in 1998, offers a highly readable account of Vincent’s life and times. Earlier treatments include Louis Abelly, Vie du vénérable serviteur de Dieu Vincent de Paul instituteur et premier superieur général de la Congrégation de la Mission (Paris: F. Lambert, 1668) and Pierre Coste, Le grand saint du grand siècle. Monsieur Vincent (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer et cie, 1934).

- Barbara Diefendorf, From Penitence to Charity: Pious Women and the Catholic Reformation in Paris (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004); Susan E. Dinan, Women and Poor Relief in Seventeenth-Century France: The Early History of the Daughters of Charity (Woodbridge: Ashgate, 2006); and Elizabeth Rapley, The Dévotes: Women and Church in Seventeenth-Century France(Buffalo, N.Y.: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990).

- John C. Bowes, “St. Vincent de Paul and Business Ethics,” Journal of Business Ethics 17(1998):1663-1667.

- Raised in a strictly Catholic household, Beauvoir later gave up her belief but not her intellectual fascination with theology. See in particular Joseph Mahon, Simone De Beauvoir and Her Catholicism: An Essay on Her Ethical and Religious Meditations (Spiddal, Ireland: Arlen House, 2007).

- See Colin Jones, The Charitable Impulse: Hospitals and Nursing in Ancien Régime and Revolutionary France (New York: Routledge, 1989); Catherine Duprat, Usage et pratiques de la philanthropie, pauvreté, action sociale et lien social à Paris, au cours du premier XIXe siècle, 2 vols. (Paris: Comité d’histoire de la securité sociale, 1996-9); Evelyne Lejeune-Resnick, Femmes et associations (1830-1880), vraies démocrates ou dames patronnesses? (Paris: Publisud, 1991); Jean-Noël Luc,L’Invention du jeune enfant au XIXe siècle, de la salle d’asile a l’école maternelle (Paris: Belin, 1997); and Evelyne Diebolt, Les Femmes dans l’action sanitaire, sociale et culturelle, 1901-2001: Les Associations face aux institutions. Prefaces by Michelle Perrot and Emile Poulat (Paris: Femmes et Associations, 2001).

- Gillian Weiss, Captives and Corsairs: France and Slavery in the Early Modern Mediterranean (Palo Alto, Cal.: Stanford University Press, 2011).

10 minute clip from the movie on YouTube at this link.