Michael G. Vann

Sacramento State University

Historians can be a risk averse community. Perhaps it is our training to be patient and methodical in the archives or it could be the hangover of empiricism. But compared to fields such as anthropology, sociology, or cultural studies our monographs and journal articles can be fairly conventional. While there are some important exceptions, our colleagues often express concern with overly theoretical writing. World historians, whose subfield challenges the traditional dominance of the nation-state as the parameter for historical analysis, know the field’s resistance to change all too well. For those of us climbing the professional ladder there is the anxiety that projects in digital humanities, podcasts, web-based publications, or scholarship aimed at the general public might raise eyebrows amongst senior tenure review committee members. Innovation is not always welcome.

Trust me, I just wrote a comic book about sewer rats in colonial Vietnam and the Frenchmen who tried to kill them. If I can modestly say that my work has so far been well-received from those who have read it, I have seen a few curious and even skeptical looks as I have explained that The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt: Empire, Disease, and Modernity in French Colonial Vietnam is a graphic history. I regularly have to correct colleagues who call it a “graphic novel,” a term that has only recently gained common usage.[1] While most people who mistakenly call it a graphic novel do so out of respect for the serious use of the comic genre, I am obliged to remind them politely that novels are works of fiction and that The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt is the product of years of scholarly research.

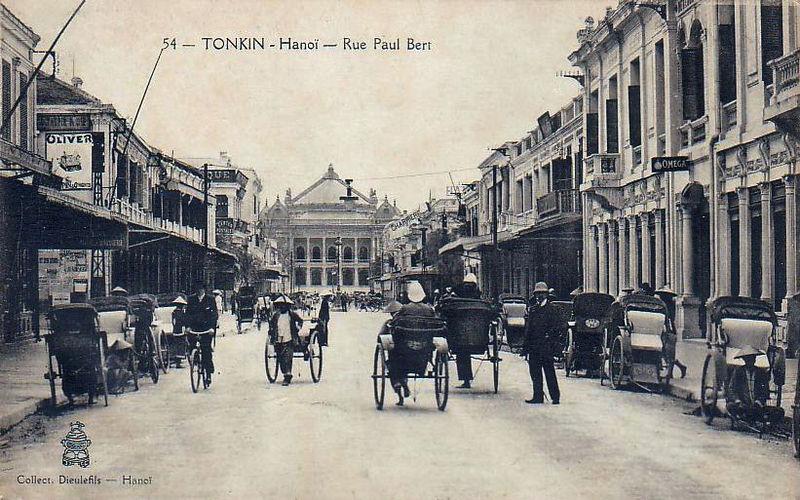

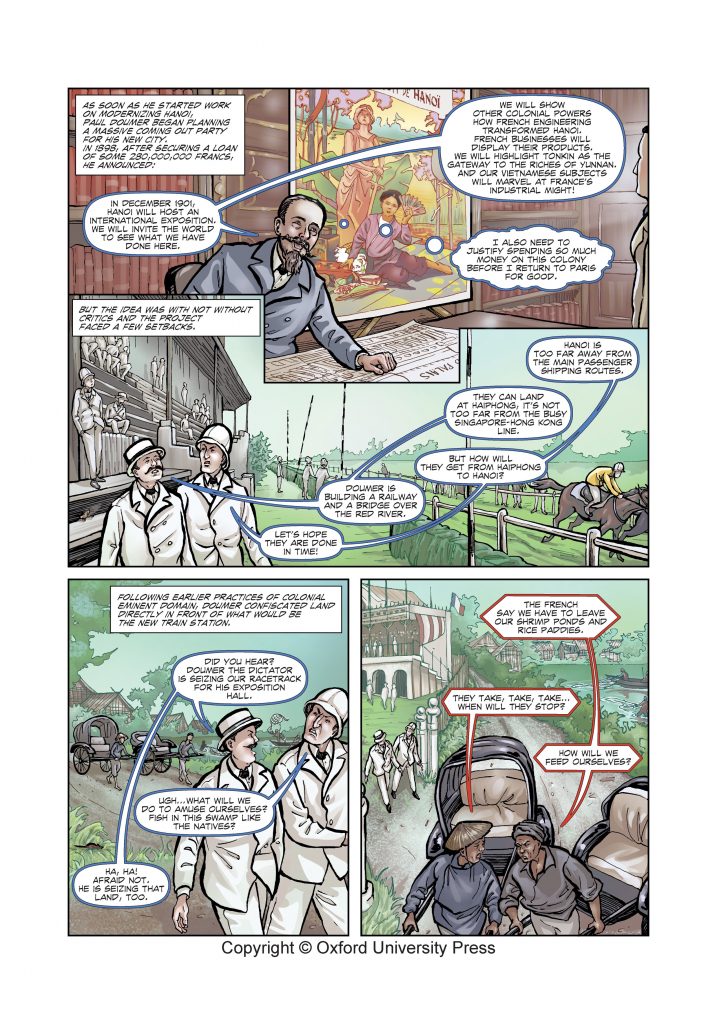

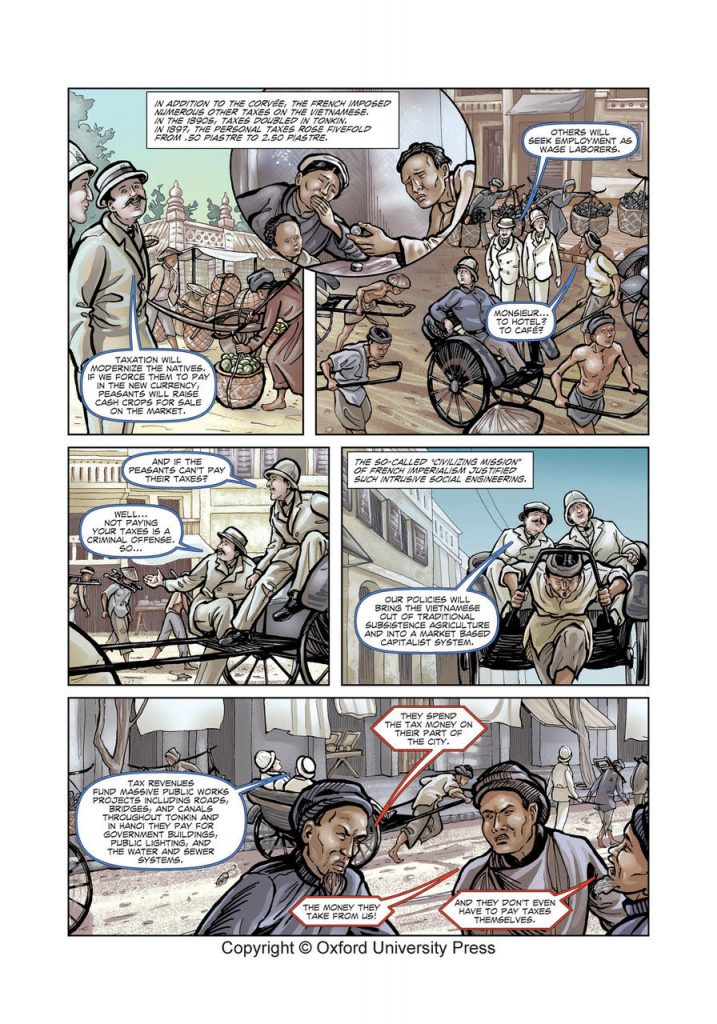

The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt is a micro-history. It is the story of the French efforts to modernize Hanoi, a city which they ruled from 1883 to 1954. As conquerors, the French displayed contempt for Vietnamese urban traditions, even questioning whether Hanoi was really a city or just an agglomeration of villages. Military officers and civilian administrators were particularly concerned with the city’s perceived health issues. Celebrating Haussmann’s renovation of Paris, especially his work on the city’s sewer system, colonial officials believed that modern urbanism would create a healthier Hanoi.[2] Amongst their other public works projects, the French created a state-of-the-art sewer system. However, the logic of colonial white supremacy determined that while the spacious villas of the French neighborhoods would have running water and flush toilets, the Vietnamese and Chinese would only get public fountains and a rudimentary drainage system. They inscribed race within the body of the city itself. They also established a modern transportation network. Railways to China and Haiphong and steamship lines to Saigon, Hong Kong, and Shanghai were to make Hanoi an important regional hub, promising great prosperity. However, the advent of this global transportation system coincided with the start of the Third Bubonic Plague Pandemic (1855-1959). China’s nineteenth-century socio-economic crises and a series of Western imperial intrusions led to the reappearance of plague in its rural rodent reservoirs in highland Yunnan, which made its way into Canton and then Hong Kong in the 1890s. French scientists in Asia such as Alexandre Yersin and Paul Simond identified the plague bacillus and the role of rat fleas as vectors in the spread of the disease, just as trains and steamers brought an invasive species of rats from southern China into Hanoi. The new arrivals quickly discovered that the sewer system was an ideal ecosystem, free of predators and full of all the things rats love: filth, shelter from predators, and somewhere to reproduce.

By 1902, the situation was so bad that the French neighborhoods reported rats coming out of the toilets. When the plague reached Hanoi, much to the horror of the French state, there were fatalities, not just in the Asian neighborhoods, but in the rat-infested French quarter, belying France’s civilizing mission. The municipal authorities decided to stem the crisis by eliminating sewer rats. Initially, they forced city employees to kill the rodents, but these skilled workers quickly refused the disgusting task. The colonial state then offered a bounty on every dead rat turned into city hall. Faced with hundreds of rat corpses, possibly containing infected fleas, they quickly announced that only the tails of dead rats were wanted. From April into July, this plan seemed to be a great success. For weeks on end, thousands of rat tails were exchanged for the reward. One day over 20,000 tails were handed in. But, in July an official reported seeing a rat with no tail in the suburbs. Evidently local Vietnamese were catching rats but only cutting off their tails, allowing the rodents to reproduce. Subsequent investigations revealed rat farms and a region-wide smuggling network bringing rats to Hanoi. The French officials threw up their hands in despair and abandoned the scheme. Faced with a series of plague outbreaks, the colonial state turned to increasingly intrusive and invasive public health measures, including the burning of victims’ homes, quarantining suspected individuals, and burning the bodies of infected corpses. While these practices were in keeping with Western science, such actions infuriated the Vietnamese community and fanned the flames of anti-colonialism.

By 1902, the situation was so bad that the French neighborhoods reported rats coming out of the toilets. When the plague reached Hanoi, much to the horror of the French state, there were fatalities, not just in the Asian neighborhoods, but in the rat-infested French quarter, belying France’s civilizing mission. The municipal authorities decided to stem the crisis by eliminating sewer rats. Initially, they forced city employees to kill the rodents, but these skilled workers quickly refused the disgusting task. The colonial state then offered a bounty on every dead rat turned into city hall. Faced with hundreds of rat corpses, possibly containing infected fleas, they quickly announced that only the tails of dead rats were wanted. From April into July, this plan seemed to be a great success. For weeks on end, thousands of rat tails were exchanged for the reward. One day over 20,000 tails were handed in. But, in July an official reported seeing a rat with no tail in the suburbs. Evidently local Vietnamese were catching rats but only cutting off their tails, allowing the rodents to reproduce. Subsequent investigations revealed rat farms and a region-wide smuggling network bringing rats to Hanoi. The French officials threw up their hands in despair and abandoned the scheme. Faced with a series of plague outbreaks, the colonial state turned to increasingly intrusive and invasive public health measures, including the burning of victims’ homes, quarantining suspected individuals, and burning the bodies of infected corpses. While these practices were in keeping with Western science, such actions infuriated the Vietnamese community and fanned the flames of anti-colonialism.

This formed a sub-section of my 1999 doctoral dissertation on colonial whiteness in French Hanoi, and I published it as an article in a 2003 volume of French Colonial History.[3] The article has had a surprisingly wide readership, making its way onto a number of college syllabi. It even led to an interview on public radio’s popular Freakonomics –I had apparently illustrated the economic principle of “perverse incentive.”[4] A decade later, while planning a traditional monograph, I decided to take things in a different direction. Eschewing the conventional 250-pages of prose, I plunged into the genre of graphic history. My decision was based on the belief that the genre offered unique opportunities to communicate essential elements of my larger argument about race and modernity in the French empire. Furthermore, the graphic format would allow me to broaden my analysis from an urban history of Hanoi, to a regional study of Southeast Asia, and a global analysis of the world system.

Fortunately for me, I was able to ride on to the coattails of Trevor Getz, the pioneer of graphic history. His Abina and the Important Men came out with Oxford University Press in 2012.[5] The first in the publisher’s Graphic History series, Abina is the product of a collaboration between the San Francisco State’s professor of African history and Liz Clarke, an illustrator based in Cape Town. The core of the book rests on Getz’s archival research on Abina, a woman enslaved in the 1870s who used the British courts to sue for her freedom. The story is an amazing tale of an individual exercising historical agency against powerful institutions of empire and patriarchy. On its own, Getz’s micro-history opens a window on how individuals make their own histories. It further shows how institutionalized systems of power ranging from tribal associations to British courts have silenced the voices of people like Abina. But the true genius of Abina is the ways in which Clarke brings Abina the woman to life. Her graphic recreation of Abina and the societies in which she lived humanizes her in a manner than transcends the limitations of conventional academic prose. As a graphic history, Abina uses the genre to explain historical methods to the reader. Following the comics tradition of breaking down the fourth wall between author/artist and audience, the illustrations show not only the primary source documents that Getz used in his research, but they also depict the young researcher going to the archives, searching for traces of Abina’s all but forgotten life. The book humanizes both the subject and the historian. Clarke and Getz’s collaboration won the American Historical Association’s James Harvey Robinson Prize for the best “teaching aid” and the book has been used in a wide range of classroom settings around the world. Inspired by Abina, I approached the series editor about turning my research into a graphic history.

So what did the graphic format offer my story of rat-hunting in Hanoi that traditional academic prose would not? Before answering that question, I should note that not every research project can or should be turned into a graphic history. Intellectual history, such as theological debates, might not be suitable for the genre. Indeed, I fail to understand why a recent graphic biography of Hannah Arendt is in the comics format; by contrast, Kate Evans’ “graphic biography” of Rosa Luxemburg is a wonderful success.[6] There needs to be a good reason to put academic work into the comic form. As Marshall McLuhan would put it, there should be synergy between medium and message. Using the metaphor of Jews as mice and Germans as cats, Art Spegielman’s account of his father’s survival of the Shoah is perhaps the best-known and arguably most successful graphic history ever produced.[7] Two graphic memoirs of the Vietnamese diaspora, GB Tran’s Vietnamerica and Thi Bui’s The Best that We Could Do, are more recent examples of what comics can do for historical writing.[8] Graphic histories should not just be a different way of telling the past– or worse a form of pandering to younger audiences–, but rather enhance this telling. Nick Sousanis’s Unflattening, originally his doctoral dissertation in education at Columbia University, is perhaps the most impressive scholarly use of the graphic format.[9] Both Abina and The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt are quirky and unusual tales so that their intriguing narratives lend themselves well to graphic story-telling, and can reach a wider audience than a purely academic one. When presented in the unusual style, medium and message can work together.

So what did the graphic format offer my story of rat-hunting in Hanoi that traditional academic prose would not? Before answering that question, I should note that not every research project can or should be turned into a graphic history. Intellectual history, such as theological debates, might not be suitable for the genre. Indeed, I fail to understand why a recent graphic biography of Hannah Arendt is in the comics format; by contrast, Kate Evans’ “graphic biography” of Rosa Luxemburg is a wonderful success.[6] There needs to be a good reason to put academic work into the comic form. As Marshall McLuhan would put it, there should be synergy between medium and message. Using the metaphor of Jews as mice and Germans as cats, Art Spegielman’s account of his father’s survival of the Shoah is perhaps the best-known and arguably most successful graphic history ever produced.[7] Two graphic memoirs of the Vietnamese diaspora, GB Tran’s Vietnamerica and Thi Bui’s The Best that We Could Do, are more recent examples of what comics can do for historical writing.[8] Graphic histories should not just be a different way of telling the past– or worse a form of pandering to younger audiences–, but rather enhance this telling. Nick Sousanis’s Unflattening, originally his doctoral dissertation in education at Columbia University, is perhaps the most impressive scholarly use of the graphic format.[9] Both Abina and The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt are quirky and unusual tales so that their intriguing narratives lend themselves well to graphic story-telling, and can reach a wider audience than a purely academic one. When presented in the unusual style, medium and message can work together.

But I had several other reasons for turning my work into a graphic history. They were both global and local. Since much of my research is in the field of urban history, where architecture and place matter so much, being able to show hundreds of images of Hanoi before, during, and after French colonial rule was a tremendous opportunity. Rather than describing neo-classical architecture or the transformation of Hanoi’s thirty-six hàng (traditional Vietnamese streets dedicated to a specific craft or product) into a modern urban space, I could actually show the reader what these historical processes looked like. While most monographs might have a few black and white photos and maps, and only rarely expensive color plates, every page of my graphic history recreates Hanoi in vivid color. Because my period is the turn of the twentieth-century, I was able to send Liz Clarke hundreds of photographs to help her design her cartoon images. The insertion of narrative text into these visual presentations allowed me to guide the reader through Hanoi’s urban history in a way that conventional academic prose would not.

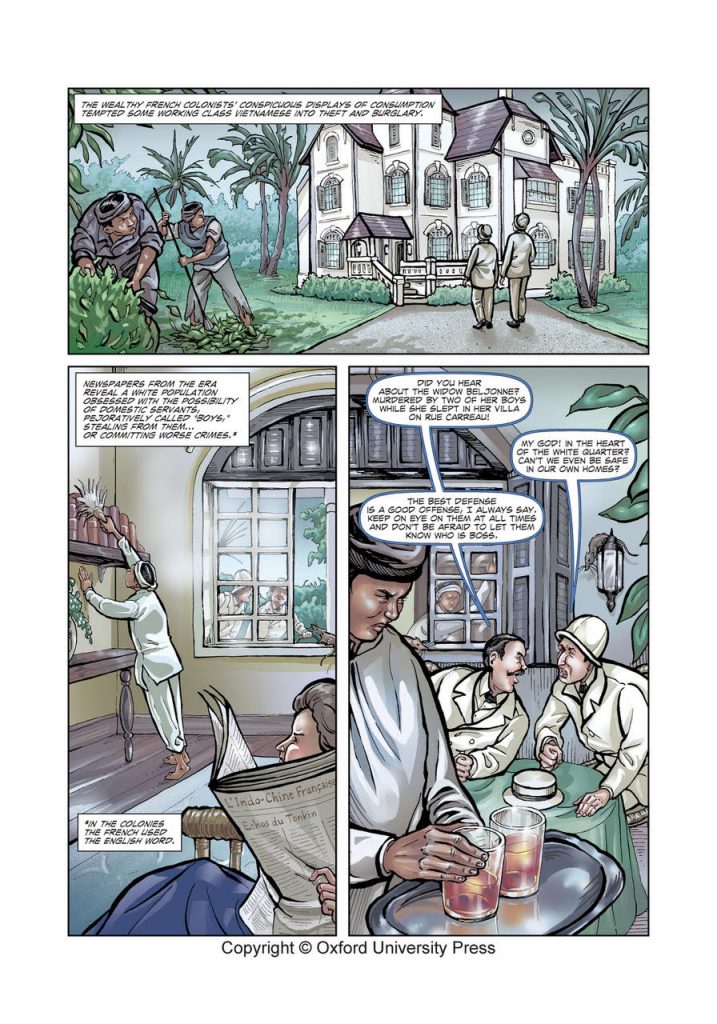

As a cultural historian interested in the asymmetric power relations of colonialism’s hybrid urban spaces, the graphic format allowed me to recreate what Mary Louise Pratt called the “cultural contact zone.” Colonial urbanism tried to manage city space, creating certain neighborhoods for designated activities and separating racial groups. With the quartier system, the colonial state inscribed white supremacy within the city’s make-up, yet the practical aspects of colonial rule and of the city as an economic system meant that colonizer and colonized, white and non-white, frequently shared the same physical space. Vietnamese laborers and servants worked in the French quarter and many French visited the so-called “native quarter” for nocturnal entertainment. Thus, the practice of daily life required a constant transgression of urban racial boundaries. By using illustrations, The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt constantly reminds the reader of the ways in which colonial cities mixed populations that held unequal power.

As a cultural historian interested in the asymmetric power relations of colonialism’s hybrid urban spaces, the graphic format allowed me to recreate what Mary Louise Pratt called the “cultural contact zone.” Colonial urbanism tried to manage city space, creating certain neighborhoods for designated activities and separating racial groups. With the quartier system, the colonial state inscribed white supremacy within the city’s make-up, yet the practical aspects of colonial rule and of the city as an economic system meant that colonizer and colonized, white and non-white, frequently shared the same physical space. Vietnamese laborers and servants worked in the French quarter and many French visited the so-called “native quarter” for nocturnal entertainment. Thus, the practice of daily life required a constant transgression of urban racial boundaries. By using illustrations, The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt constantly reminds the reader of the ways in which colonial cities mixed populations that held unequal power.

Juxtaposing colonizer and colonized in the same images gave me the opportunity to illustrate other aspects of colonial culture, including the paradoxical relationship between white colonialists’ power and their sense of vulnerability. Milton Osbourne has written about the “background anxiety” that weighed on the minds of many French in Southeast Asia.[10] While they were at the apex of the colonial socio-political hierarchy, white residents fretted about various forms of native resistance from petty crimes to murder to violent rebellion. In what might be termed the “colonial gothic,” the colonizer was fearful, always on his guard against hidden threats. Even in the safety of their own homes, which could be spacious villas, French men and women expressed concern about their Vietnamese and Chinese domestic servants. Liz and I illustrated this in one page of the book. In three cells, we see how colonizer and colonized kept a watchful eye on each other.

Juxtaposing colonizer and colonized in the same images gave me the opportunity to illustrate other aspects of colonial culture, including the paradoxical relationship between white colonialists’ power and their sense of vulnerability. Milton Osbourne has written about the “background anxiety” that weighed on the minds of many French in Southeast Asia.[10] While they were at the apex of the colonial socio-political hierarchy, white residents fretted about various forms of native resistance from petty crimes to murder to violent rebellion. In what might be termed the “colonial gothic,” the colonizer was fearful, always on his guard against hidden threats. Even in the safety of their own homes, which could be spacious villas, French men and women expressed concern about their Vietnamese and Chinese domestic servants. Liz and I illustrated this in one page of the book. In three cells, we see how colonizer and colonized kept a watchful eye on each other.

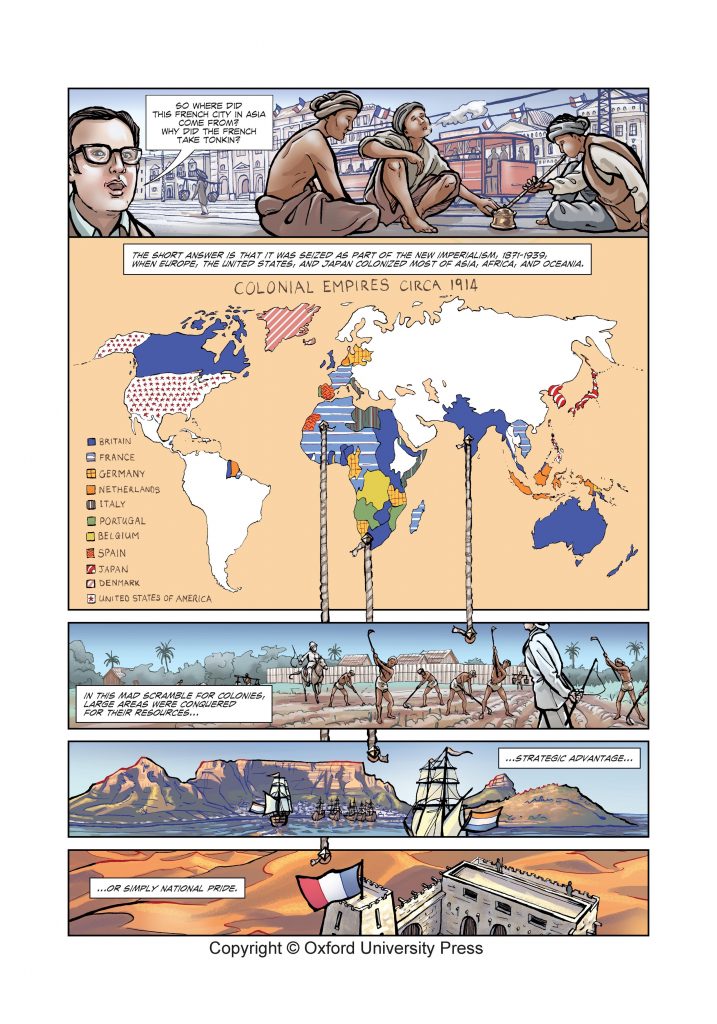

I was also trained in the field of world history. To place this story of rats and men in a global context, Liz Clarke and I used a series of maps. We integrated maps of European imperial holdings, the international trafficking of Indian and Chinese “coolie” laborers, and of the flow of goods such as spices, silver, and opium.[11] Inspired by Janet Abu-Lughod‘s way of placing urban sociology into the world system, we were able to situate seemingly local events into a larger discussion of world historical processes.[12] My goal was to help the reader understand colonial Hanoi as part of the era of high global imperialism.

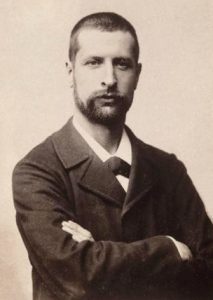

While The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt is a work of archival research grounded in established historiographies of empire, Vietnam, and disease, making the story work in the comics format required some creative thinking. One of my decisions flirts dangerously close with the boundaries of history. In response to my initial proposal, my editor at Oxford argued that graphic histories need characters. I countered that Hanoi was a character, but he politely disagreed. The book does contains a number of historical figures, but they move in and out of the story. In order to create narrative continuity, I created two characters. Inspired by Baudelaire and Walter Benjamin, I thought of them as “flâneurs.”[13] They were two privileged white Frenchmen who walk about the city commenting on the events unfolding before them. They serve as a Greek chorus, guiding the reader through the story. They also embody the real historical phenomenon, about which I’ve written elsewhere, of the white man imagining the colonial city as his private fantasy land.[14] I was admittedly nervous about this literary conceit. For the historical figures such as Paul Bert, the first French civilian administrator of Hanoi, and Paul Doumer, the Governor General of French Indochina, I drew from published sources such as memoirs or archival documents, but I had to invent the flâneurs’ dialogue.

This does indeed come dangerously close to fiction but, whatever you do, don’t call The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt a novel.

Michael G. Vann and Liz Clarke, The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt: Empire, Disease, and Modernity in French Colonial Vietnam (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019).

NOTES

- Jenny Stringer, “Graphic novel.” The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century Literature in English (New York: Oxford Univserity Press, 1996): 262.

- Gwendolyn Wright, The Politics of Design in French Colonial Urbanism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991) & David Harvey, Paris, Capital of Modernity (New York: Routledge, 2003).

- Michael G. Vann, “Of Rats, Rice, and Race: The Great Hanoi Rat Massacre, an Episode in French Colonial History,” French Colonial History Society (2003).

- “The Cobra Effect,” Freakonomics: http://www.freakonomics.com/2012/10/11/the-cobra-effect-a-new-freakonomics-radio-podcast/.

- Trevor Getz, Abina and the Important Men (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

- Ken Krimstein, The Three Escapes of Hannah Arendt (New York: Bloomsbury, 2018) & Kate Evans Red Rosa: A Graphic Biography of Rosa Luxemburg (New York: Verso, 2015).

- Jeanne Ewert, “Art Spiegelman’s Maus and the Graphic Narrative.” in Ryan, Marie-Laure. Narrative Across Media: The Languages of Storytelling (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004): 180–193.

- GB Tran, Vietnamerica: A Family’s Journey (New York: Villard, 2010) & Thi Bui, The Best We Could Do: An Illustrated Memoir (New York: Abrams Comicarts, 2017).

- Nick Sousanis, Unflattening (Harvard University Press, 2015).

- Milton Osborne, “From Conviction to Anxiety: Reassessing the French Self-Image in Viet-Nam” (Flinders University Asian Studies lecture 7, 1976) & “Fear and Fascination in the Tropics: A Reader’s Guide to French Fiction on Indochina” (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 1986).

- Kenneth Pomeranz & Steven Topik, The World That Trade Created: Society, Culture, and the World Economy, 1400 to the Present, Third Edition (Armonk and London: M.E. Sharpe, 2013) is a lively collection of essays on a variety of engaging world history topics.

- Janet L. Abu-Lughod, Cairo: 1000 Years of the City Victorious (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1971), Rabat, Urban Apartheid in Morocco (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980) & Before European Hegemony: The World System, 1250-1350 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989).

- Charles Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life (New York: Da Capo Press, 1964) and Walter Benjamin, The Writer of Modern Life: Essays on Charles Baudelaire (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 2006).

- Michael G. Vann, “Sex and the Colonial City: Mapping Masculinity, Whiteness, and Desire in French Occupied Hanoi,” Journal of World History, Vol. 28, Nos. 3 & 4 (2017) & “(Colonial) Intimacy Issues: Using French Hanoi to Teach the Histories of Sex, Racial Hierarchies, and Geographies of Desire in the New Imperialism,” World History Connected October 2018: http://worldhistoryconnected.press.uillinois.edu/15.3/forum_vann.html.